Moscow’s cultural avant-garde may not be in the hands of the contemporary art system. For many, this could be difficult to acknowledge. But in the aftermath of the opening of the Garage Museum’s new building, which took place on June 12, it seems that art discourse in the Russian capital — and perhaps in the whole country — is still seeking a distinct strategy in the face of the post-Soviet vacuum. After all, the most positive neoteric offering to emerge in this context, at least for me, has been the street wear of Gosha Rubchinskiy, a Moscovite photographer and fashion designer. Across only five seasonal collections, Rubchinskiy has managed to frame and convey to the world a specific imaginary of the New Russia that relies not on invention but rather on a disillusioned take on the failed project of the Soviet Union.

Contrary to Rubchinskiy’s clear-cut and realist approach, the Garage’s mission — a two-fold program that wants to combine a zealous xenophilia with a search for the true roots of Russian contemporary art — lacks, at least from what I could glean in its first iteration in this new building, a clear focus. In fairness, I had to take in an overabundant number of projects, evidently dictated by the frenzy of showing off the manifold activities of the cultural institution; and I felt oppressed by a latent stiffness in the museum’s ethos, as if nothing here had been given the benefit of the doubt, or allowed to mirror the vulnerability of a still precarious cultural landscape. The program seems instead to be built on the alleged knowledge of How We Must Lead Russia’s Art System into the Future — a presumption which, resonating in a former Socialist landmark like this new location, perhaps risks giving rise to another collective utopia.

Located in the recently revitalized Gorkij Park, Garage Museum’s new home is OMA/Rem Koolhaas’s conversion of the Vremena Goda, a prototypal restaurant erected in 1968 but soon neglected and never reproduced. OMA’s project respectfully and tastefully preserves many of the building features, from the basic spatial organization to surface decorations, in an attempt to emphasize what Koolhaas calls “the generosity of Soviet architecture” — a quality that doesn’t translate merely into capacity, but also into openness, receptiveness and the building’s ability to epitomize social values. Indeed, the architects gave the Museum a polycarbonate skin with two gigantic openings, rendering the site extremely porous to the life of the park.

Yayoi Kusama and Rirkrit Tiravanija’s exhibitions (the first in Russia for both artists) are the highlights of the opening program. While Tiravanija’s interventions wittily engage the Russian social landscape and the history of the building — he set up ping-pong tournaments, served pelmeni (Russian dumplings) and installed a DIY T-shirt factory, hosting both these activities within “pavilions” resembling typical Soviet bus stops — Kusama’s installations poorly convey any content besides their spectacular nature. It is here, in a mirrored room filled with pulsating lights that seem to strive to replicate the universe, or in the presence of trees wrapped in fabric bearing the artist’s famous red polka dots, that the Garage Museum’s overall narrative appears problematic. What sort of empowering educational or social dialogue can be pursued within a program that chooses to develop a project by an artist who is today a self-caricature, and who, notably, disseminates installations without even traveling to the sites of their execution?

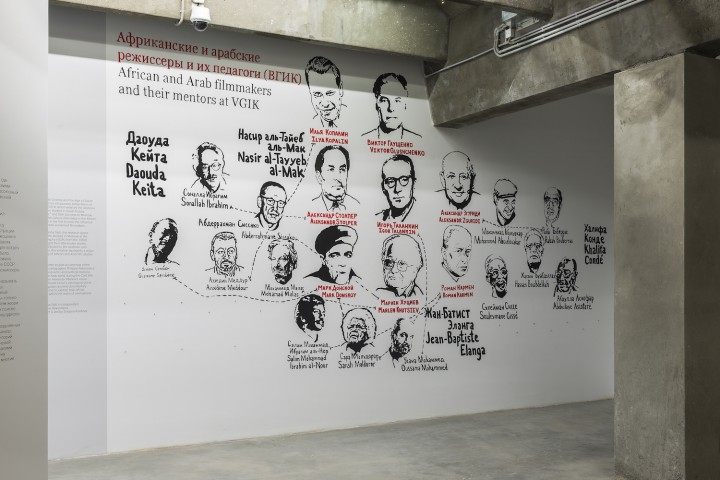

It must be mentioned that the Kusama and Tiravanija shows are presented amid a number of side projects based on cross-disciplinary and theoretical investigations of underexplored topics of Russian culture. Three installments of the Museum’s so-called “Field Research” platform offer insights into subjects such as Cosmism, a late 19th-century philosophical movement that advocates for the idea of cosmos as a universal order; the production of African and Arab filmmakers who studied in the USSR from the 1960s to the late 1980s; and the resonance on the Russian lifestyle of the American National Exhibition, held in Moscow in 1959, which showcased US achievements in the fields of technology, fashion, manufacturing and culture.

While Anton Vidokle’s This is Cosmos, the first film in a trilogy that the artist planned in the context of the “Field Research” platform, addresses hypothetical resonances of ideas related to Cosmism in our technology-driven reality and is a fascinating work of video art, the displays “Saving Bruce Lee: African and Arab Cinema in the Era of Soviet Cultural Diplomacy” and “Face-to-face: The American National Exhibitions in Moscow, 1959/2015” are nothing more than didactic gatherings of materials, often installed in suffocating, hard-to-decipher clusters. They are, in a word, stodgy. Let’s clearly state this: all these projects are “prologues,” early stages of what are undeniably licit and compelling research trends. But, one has to ask if the role of a cultural institution is to “show” research to its audience, regardless of the celebratory occasion, or rather to deliver findings, share methodologies and at least excogitate the right presentational format. (On June 30, the curators of “Saving Bruce Lee” will host a one-day seminar; this event will probably offer more than a display of film posters and a wall map diagramming the filmmakers’ intercontinental travel itinerary.)

It goes without saying that the future of Russia’s cultural landscape is tied to the future of the Garage Museum — and of other international, dedicated and genuinely experimental institutions that emerged in post-Soviet Moscow, such as the Strelka Institute and the V-A-C Foundation. In the fall, the Museum will open a major Louise Bourgeois retrospective. But the question of whether contemporary art will be able to play a progressive role in Russia remains. On June 12 another cultural institution was shut down by local authorities: the artist-run space Red Square, located in the Elektrozavod, a dismantled factory complex that has been taken over by artist studios and creative agencies over the last decade. Red Square was hosting the exhibition “Be Yourself: Stories of LGBT Teenagers,” a collection of portraits of young gay people, among the most persecuted communities in Russia today. This is just one of the serious, deeply rooted social issues that we all expect a liberal and forward-looking cultural institution to promptly address.