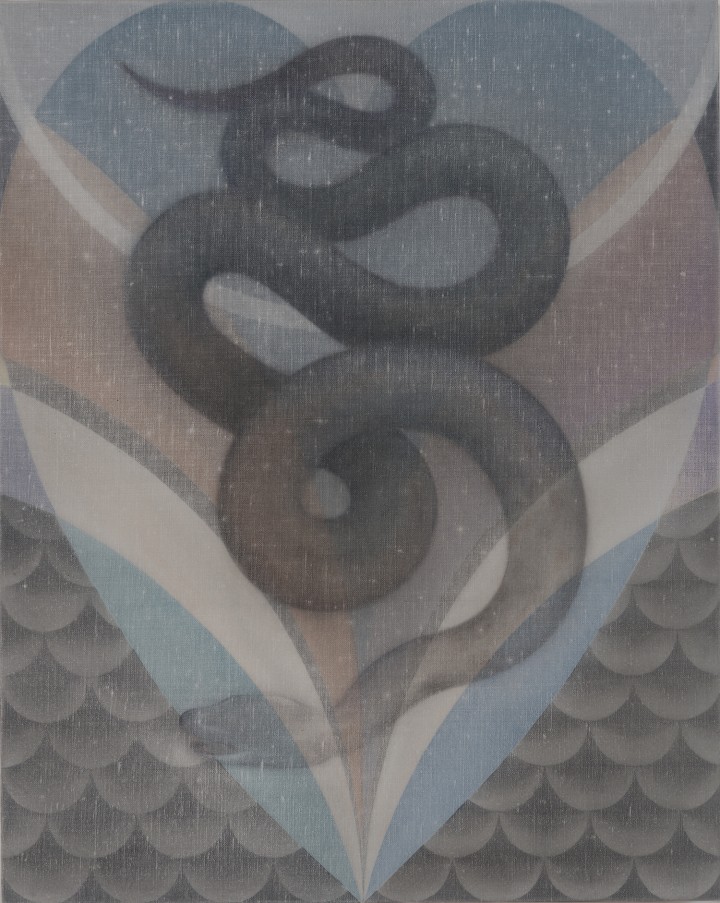

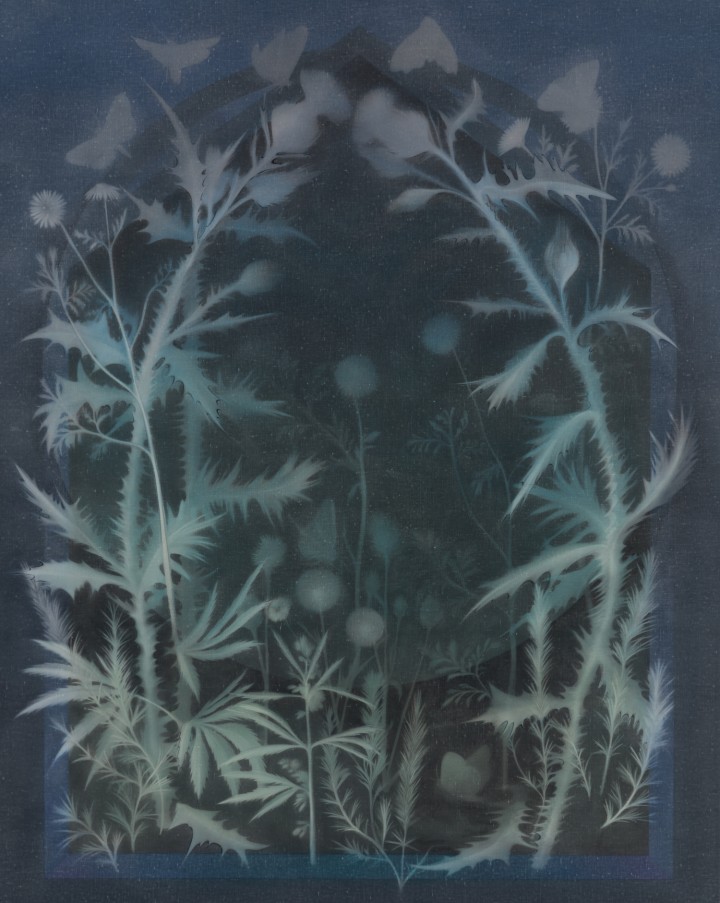

Theodora Allen’s paintings have the lived-in feel of worn denim or vintage t-shirts. They are executed in light hues of blue, purple and green, all washed into a mood of late-afternoon burning into evening. However, image-wise, they start with a hard graphic impulse, asserting strong shapes like arcs or diamonds as stabilizing structures that are subsequently filled with enigmatic pictures of plants, guitars, snakes, hourglasses, and a face in profile.

Odds are that many viewers will use the word “romantic” to describe Allen’s paintings, and it is true that many of the pictures reference both historical romanticism and mushier definitions of the term that populate the present. Allen’s particular use of graphics has a decidedly spiritualist feel, not unlike the pictorial strategies of Symbolist painters like Ferdinand Hodler, who sought to discover symmetry amid the wilder rhythms of nature.

However, Allen’s take on this tradition is less high-minded romanticism and more an interpretation of romanticism filtered through California hippie culture, revived album covers, and the youthful jouissance found in grainy photographs of 1960s and 1970s America. When viewing her paintings, one is reminded of the amber-lit afternoon photo shoots of Gram Parsons or Joni Mitchell picking flowers on the side of Laurel Canyon. It is less Hodler and more the suit designs of Nudie Cohn that inspire Allen.

From these moments handed down to us via documentaries and vinyl, Allen’s snakes and twisting vines rise like totems, close cousins to the giant lips of the Rolling Stones or the emblem of Shelby Cobras rising from the hoods of Ford Mustangs. The paintings seem to pointedly suggest that there is always a bit of marketing involved in American romance, that it is always as much of a fashion as a feeling.

Art critic Robert Hughes once said, to paraphrase, that the United States’ obsession with the new is only matched by its equally overwhelming nostalgia for the past. Allen’s painting enacts this American tale once again: the constantly advertised dream of freedom in America is often only partially felt through projected image of a recently vanished history.