At the end of September 2013, Flash Art invited Gisèle Vienne to present the performance Jerk at MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, in collaboration with the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater.

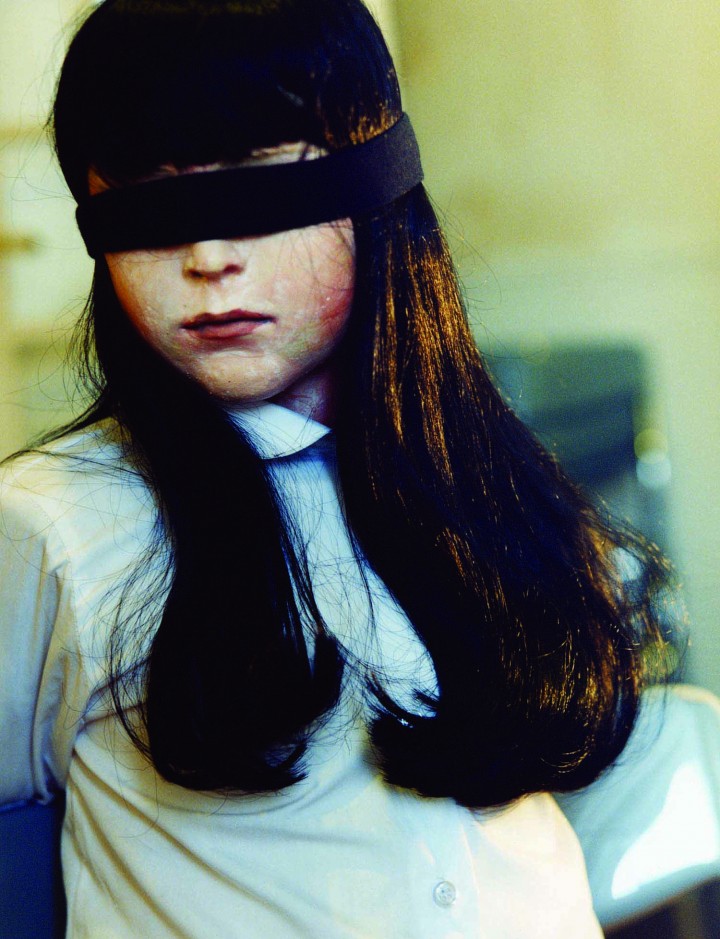

Jerk is an imaginary reconstruction of the crimes perpetrated by American serial killer Dean Corll who, with the help of teenagers David Brooks and Wayne Henley, killed more than twenty boys in the state of Texas during the mid-1970s. The show sees David Brooks serving his life sentence. In prison, he learns the art of puppetry and writes a show that reconstructs the murders committed, performing it for a class of psychology students from a local university. Based on a novel written by Dennis Cooper and performed by Jonathan Capdevielle, the performance utilizes and masters, in a mesmerizing yet disturbing way, specific tools and skills drawn from puppetry and ventriloquism. The performance was presented for the first time in March 2008 and since then has toured all over the world, bringing Gisèle Vienne recognition as one of the most influential choreographer of her generation. Flash Art sat down with the artist before the beginning of the last performance of Jerk in Los Angeles.

How did you first get in touch with Dennis Cooper?

Gisèle Vienne: My first connection with Dennis Cooper was his books. In 2003, I started to work on the performance I apologize, and that’s when I wanted to collaborate with him. As he was living in Los Angeles at that time and I was living in Paris, we started a written correspondence for several months, and I introduced him to my oeuvre. I really wanted to have a collaboration that came out of an intense and sincere artistic dialogue. I wanted him to write for the work and be part of the work and he came over to France. I wasn’t sure if we could work together and have a real artistic dialogue, so I invited him to work for a few days to see if we could really exchange ideas. These few days were kind of miraculous! On the first day we discovered some things were super obvious to say and we didn’t have to say them anymore; we knew what each of us was talking about, it was very obvious. I would call it an artistic crush. That’s how it all started. We were very enthusiastic and excited, we were supposed to work on one performance only, but we haven’t stopped since then, and now it’s been nine years that we are collaborating.

You are showing your work in Los Angeles for the first time. It’s a special occasion for you and for him.

It’s very special for us to play here. Cooper’s literature is something that comes out of LA’s culture directly. The reaction of the audience is always very different in each city, and I’m very used to different layers of reaction: you have the immediate reaction, the reaction two days later, the reaction six months later. But what I noticed about yesterday already is that here you can hear the audience’s reaction — they are laughing, making noises, you can see their bodies moving. I have other pieces where you can see how focused the audience is, and you cannot guess what goes on inside them, but in Jerk we play with conscious theatrical tools that make people laugh or become scared at very specific points. I’m always surprised at how efficient it is. But people react more strongly here than usually.

The cultural references are really different. Probably here the audience has a more direct understanding of the content of Jerk.

People here really know the story. Sometimes in Europe people would be less familiar with this culture. The very foundation of the piece is based on a real story that took place in Texas, and as Dennis was writing about them, they had a strong impact on him and motivated him to write. I guess it depends on every generation, but we played the piece in other cities in the US, and people know that story, which was a big and crazy one. So because the text and the story come from here, people have a better understanding of it here.

I saw Jerk in 2008, and I wonder how the piece has evolved. The performer Jonathan Capdevielle has changed a lot.

I would say that the piece is growing with him in a very organic way. It’s adjusting him. Sometimes he looks younger, older, more hairy, more clean, and his mood is very different too. He has a hyper-realistic way of interpreting it, a very emotional one too. He constantly has to find stimulus in his real mood so he can be more weak, more fragile, more strong, more aggressive, and his moods somehow affect the performance every night. There are a lot of little details, and I’ve never seen him repeat something. He’s always reinventing and replaying and it’s absolutely mesmerizing. Jerk has been played over two hundred times, and I think for him it’s about a game that he knows how to play.

And this is the last cycle of representation.

Yes.

The other interesting thing is that I saw it in French, and now you are playing it in English here.

I thought it’s quite funny, especially in English, as the performer has quite a strong French accent. So when he introduces the character, the lies are very obvious from the beginning. For Europeans and people from other continents, it’s about how American culture is part of our culture. I came to the States for the first time in 2007, and like most Europeans, I grew up with a strong sense of American culture. It’s something that I don’t think any other culture has — the strong sense of the news, and the culture, as if we were Americans. If you grow up in the States, I don’t know if you can understand what a crazy impact it has. The fascination with movie stars, pop stars, rock stars… The American serial killer is a really fascinating, scary topic, and then you have so many American horror movies. In Jerk there is this French performer playing an American serial killer. It brings out this contradiction of being French and feeling open to American culture. There is always a specific reaction to the piece itself about what is real and what is fiction, and all these elements are quite confusing for the audience. And it feels very realistic, because it’s based on a real story. It’s a very understandable story — it’s linear, you have all the details, he is playing it in a very realistic way, so it all feels very real, although it’s all super fake.

Since the beginning, you worked with the idea of having two or three versions of Jerk, in French, English, even Spanish. Why?

I always knew we were going to do two versions, and the main reason I also wanted Jonathan to play it in English is that I’m very concerned with the translation.

Prior to your artistic career, you wanted to become a translator?

Yes, it was one path that I followed for a couple of years and then I changed. I studied philosophy, and if I would have gone on with philosophy, I wanted to work in translation. If I think about Jerk, you cannot just translate it, or just rewrite it. Especially when it comes to literature and poetry; it is such a big drama, and each word does not have an equivalent in another language. That’s why if I work with Dennis, his texts are in English. For me it was important that we mainly played it in English, too.

I exchanged a few words with Jonathan Capdevielle yesterday and he said to me: “It’s a disgusting piece!”

Yes! One day, after the show, I heard people from the audience saying: “Oh, it’s beautiful!” It’s very kind to hear it, but this is not really the first word that I would use.

What is the first word you would use to describe this show?

I think it would be ambivalence. It’s hilarious, funny and grotesque, but it’s also really disturbing and horrifying and disgusting. It’s also very seductive. Thus I would say it’s ambivalent. That’s why it’s confusing — you laugh a lot and you can get very seduced, and then there are a lot of obscenities…

Ambivalence is a characteristic of your entire body of work, since Showroomdummies in 2001.

I hope so. I try hard.

What is the next project you are working on?

With Dennis Cooper, we just started a new project that has many links to Jerk. It’s a theatrical play that Dennis is writing, based on this convention that takes place in Kentucky, every year in July, the world’s oldest and largest ventriloquist gathering. The performance will have a documentary feeling, though it’s completely fictional. We will work on the project with a German actress and with puppeteers and with Jonathan too. We will work on it in German and then we will translate it to English. We want to premiere it in 2015. From a dramatic approach, this play is completely crazy because you have at least seven or nine actors, who have at least three voices each. I was talking with Dennis this morning about it, and I believe it’s one of the most complex things we have ever written. It’s pretty crazy. It also has a lot to do with psychological issues, and the psychological structure of a character, and which type of voice everyone will have. We will deal with complex psychological patterns — how your different voices deal with each other. This is what we are actively working on right now.