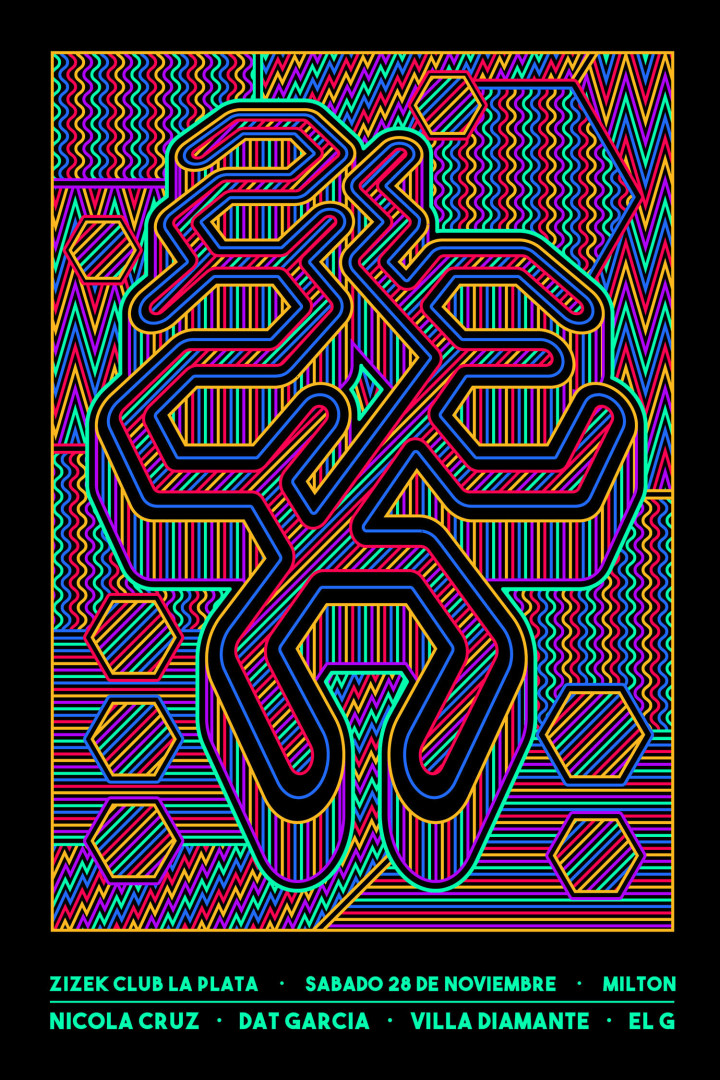

A group of people dance ceaselessly. They rub against each other. They also rub against the walls and the floor. The music is loud — a solid wall of sound comprising Peruvian cumbia and techno. It’s Saturday night in mid-summer, and Andrea Campos and Daniel Valle-Riestra, the young dupla from Lima known as Animal Chuki, are playing at Zizek, the most popular electro-cumbia party in Buenos Aires. It’s their first time in the city and at Niceto, the club that has hosted this party for over ten years.

A group of people dance ceaselessly. They rub against each other. They also rub against the walls and the floor. The music is loud — a solid wall of sound comprising Peruvian cumbia and techno. It’s Saturday night in mid-summer, and Andrea Campos and Daniel Valle-Riestra, the young dupla from Lima known as Animal Chuki, are playing at Zizek, the most popular electro-cumbia party in Buenos Aires. It’s their first time in the city and at Niceto, the club that has hosted this party for over ten years.

Zizek began as a niche Wednesday-night event: the genre of electro-cumbia had a tiny audience in its early days. Now the party is a massive celebration for a large and heterogeneous crowd. On the dance floor one finds young people new to electro-cumbia (and nightlife in general) alongside thirty-something ex-ravers who grew up with the DJs and producers who founded Zizek: Diego Bulacio, better known as Villa Diamante, Grant C. Dull and Guillermo Canale. All three are proverbial sons of Dick el Demasiado, a Dutch musician transplanted to Argentina who developed Festicumex, an experimental cumbia party that existed during the early ’00s.

Back then, this trio decided they didn’t need to look elsewhere to understand what hip was. It was enough to look to the suburbs for novelty: in the poorest neighborhoods of the country, the boom of cumbia villera (a sort of gangsta cumbia) was triggered almost at the same time as the political, economic and social crisis of December 2001.

Indeed, the aftermath of the crisis helped a new generation to understand that nightlife in Buenos Aires was nothing like that of Ibiza, New York or Berlin, and that it was not necessary to import the genres that reigned in those cities to make a party work. For the founders of Zizek, the crisis was somehow stimulating. At the time, a young DJ wouldn’t buy foreign records (which became expensive rarities after the peso devaluation), and almost no one was traveling to Europe; meanwhile the international labels with subsidiaries in Buenos Aires moved out of the country because the crisis had considerably affected their profitability. All of a sudden, the country’s ties to globalization were severed, and the music scene felt the impact. This was the spirit of the times: people in Buenos Aires began looking to culture that was produced locally. This atmosphere gave way to parties centering on marginal genres such as cumbia. “When we started doing Zizek we wanted music that had an Argentinian lineage so we could say, ‘this happens here and not anywhere else,’” says Villa Diamante in Mercurio, his record shop that only sells records by Argentinian musicians and bands. “We discovered the peculiarities of young musicians that made stuff that was more connected to the cumbia sound. In cumbia we found music that was more experimental, danceable and fun, but also elaborated and well produced.” What was previously a marginal genre was becoming mainstream.

Not only the post-crisis context favored the birth of Zizek, but also the possibility of having access to cultural content brought along by the Internet. Soulseek was the name of the post-Napster, P2P file-sharing client used extensively during the early ’00s, with which one could download thousands of songs with unprecedented ease. This tool allowed Villa Diamante and his friends to not only follow the European labels they already knew (Cologne’s Kompakt, among many others), but also to discover obscure but flourishing pockets of cumbia in countries such as Venezuela and Colombia. The Internet also allowed anyone access to postproduction tools. It therefore became easy to produce, for example, folk songs mixed with electronic beats. This is the way a typical mash up by Villa Diamante works: an uncredited track of Peruvian cumbia collides with more mainstream material, such as the voices of local singers like Gustavo Cerati, in a kind of patchwork with a very local accent. The circulation of this output through social networks like MySpace soon turned Zizek into a nexus for artists from all over Latin America. Still to this day the party brings together musicians from Peru and Ecuador who use it as a platform from which to reinterpret their country’s music, to make people dance, and to launch themselves internationally. This is very much the case with Animal Chuki and other artists working within the label.

The recognition received by several Latin American artists who had appeared at Zizek led, in 2008, to the creation of ZZK Records, a platform that, over eight years, has become a showcase for the musicians, DJs and producers passing through. Such has been the case with Chancha Via Circuito, El Remolón and Nicola Cruz, who lately joined the project and toured around Europe with a sole edited record. Consequently, one can conclude that Zizek and ZZK Records produced a sound that’s not only local, but also exportable. It’s curious to recall that until only a few years ago the primary musical output produced in Buenos Aires was rock, whose target area was that of neighboring countries such as Chile and Bolivia, while ZZK Records and other kindred labels (such as Cómeme) produce a more folkloric sound whose main destination is Europe.

Besides the host and invited DJs, sometimes you’ll find whole bands playing at Zizek. But, since it is a party and not a gig, the concert is displaced by the dance floor. By way of example, when Damas Gratis (a historical cumbia villera band) played at one of Zizek’s parties, their performance was a milestone: it was the first time the band played in an upper-class neighborhood and in front of a more mainstream audience. Before that, their shows were relegated to working-class neighborhoods such as San Fernando, where the band was formed. They toured mostly through the suburban rings of Buenos Aires, while electronic music and rave culture were, in turn, considered an attribute of the elite. This was the niche within which Zizek operated successfully. It introduced the music from the suburbs into the mental and geographical spaces inhabited by the middle- and upper-middle classes. “The Argentinian electronic music that was made in the ’90s was done for and by snobs,” says Patricio Smink, one of Zizek’s DJs. Smink states that the rise of Zizek was driven by “the Latin American boom that surged during the ’00s, which allowed cumbia to be recognized as part of the national folklore.”

This vindication of cumbia and its social implications has become a matter of state importance. During the second term of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as president (2011–15), the government organized a massive, free-entrance Damas Gratis show in the streets to close the celebration of National Day in May 2013. While the conservative press criticized it fiercely (mostly because of the allusions to drugs and crime in the band’s colorful lyrics), it was also a form of reparation, with the underlying idea that a genre that was previously considered the signature of marginalization was also a legitimate expression of national culture. “All these vindications helped us create an alternative electronic music public around cumbia,” acknowledges Villa Diamante.

In the end, one could argue that Zizek presents only a controlled version of cumbia. The spirit of the shantytown is somewhat elusive at the parties, and pivots as much toward German techno, electroclash from Chicago and many other sources. The founders of Zizek, all of them from a middle-class background, didn’t grow up next to the cumbia. Instead, they acquired it indirectly. Indeed, they were all well educated in the same international style of the ’90s they wanted to distance themselves from. This adds to the peculiarity of Zizek’s idiosyncratic sound — a sound both intellectual and popular, both local and oriented to international recognition, where folklore and tradition meet a well-produced and clearly branded style.