I tried to interview Raymond Pettibon. I thought we might have some things to talk about. We both like Joyce and hardcore and surfing. Ray, I would have said, look at all these shared interests. Except I guess he’s actually not that into hardcore: although it is practically requisite for people writing about his work to mention that they first encountered it on a Black Flag record cover (No way! Me too!), Pettibon has often insisted that he was never really into the whole punk thing. And anyway, I don’t actually surf. Still, we might have found some common ground. Maybe it would have been that we both think biting sarcasm is the only response to the long and ongoing history of American barbarism, or that we both like dumb jokes. I guess I’ll never know.

I tried to interview Raymond Pettibon. I sent an e-mail to the address listed on his website. I reached out to his galleries and was told repeatedly that maybe it would happen, but it never did. I wanted to ask him why he moved to New York. That’s what they told me at Regen Projects: Ray moved to New York a couple years ago. Not that I mind! But I wonder what that’s like for someone who has lived his whole life in — and is so intimately associated with — Los Angeles.

I wanted to ask him to design a logo for my band, which he would have been pleased to learn is not a hardcore band. Oh, the logo wouldn’t have to be as good as Black Flag’s because we’re not as good as Black Flag. In fact, we’re hardly a band at all. But I thought he might relish the opportunity to get back to his roots, to make an image intended for someplace other than the familiar confines of art galleries and catalogues.

I’m sure he’s happy with the art-world attention and accolades he’s been receiving since the early 1990s, and in no way do I begrudge him the countless shows with blue-chip galleries and museums. Pettibon is a fascinating artist and deserves all that he gets. Nor is he by any means the first artist to wear the mantle of outsider-as-insider, but the art world’s eager reception of the work does produce a tension, one perhaps best encapsulated by a large vitrine at the New Museum’s recently opened retrospective, “A Pen of All Work,” featuring dozens of his zines dating back to the late 1970s.

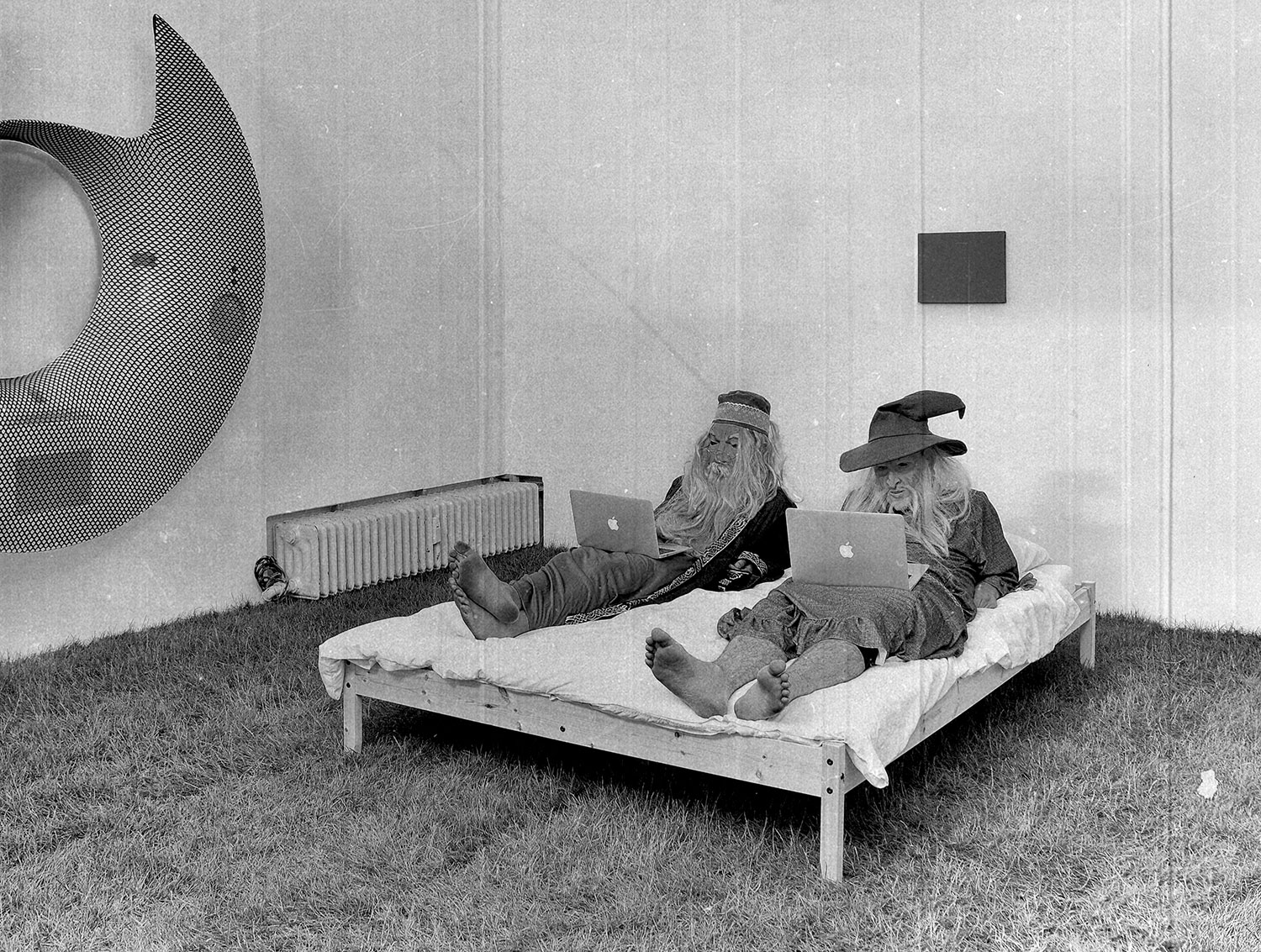

Along with album covers and fliers, zines had been the primary mode through which Pettibon’s drawings circulated through the 1980s. Xeroxed black-and-white comic books, the zines presented a pulpy extravaganza of violence, criminality and abjection, like Captive Chains (1978) or A New Wave of Violence (1982), and mordant satire, as with the hippies of the Tripping Corpse series (1981–85). Whereas the record covers and fliers, he tells us, were never really his — he just allowed his brother, Greg Ginn, to take whatever drawings he wanted and use them for his band — the zines represent the pure articulation of Pettibon’s vision from the late 1970s and ’80s.

We have all seen zines under glass before, and yes, these are artifacts on loan from the collection of Philip and Shelley Fox Aarons. I seem to recall that an iPad or some other touchscreen device had been affixed to the display, which presumably would let the visitor scroll through digital reproductions of the encased comic books, but it wasn’t working when I attended the press preview. Anyway, DAP published a collection of the complete zines in 2000, which you can find, used, in very good condition, for $350. The zine reliquary at the New Museum, however, had another job to do: it was there to authenticate Pettibon’s outsider backstory, while marking it — as if we needed a reminder — as something safely in the past. We see him always as the Black Flag guy, but also, importantly, the guy who used to be the Black Flag guy. It’s a measure of distance — the punk provenance. The obsolescence of the social and political milieu that incubated Pettibon’s snide and violent comics of sexual anxiety and juvenile delinquency facilitates the transfiguration of the drawings into happily deracinated luxury commodities.

Much of the discussion of Pettibon assumes and emphasizes his development as an artist. His roots in the LA hardcore scene are interesting, and the zines are important (if maybe only as juvenilia), but what really matters is how far he’s come. “As almost every commentator on Pettibon’s work has stated over the past twenty years,” Benjamin Buchloh writes in the catalogue to “A Pen of All Work,” “his drawing styles have been steadily shifting from the pure deskilling of his early work — by seemingly copying cartoon frames and television images — to the eventual revelation of the skills of a virtuoso draftsman and a major colorist.” Or as Gary Carrion-Murayari puts it in his contribution to the catalogue: “In the stage of Pettibon’s career from the late ’80s to mid-’90s, the tenor of his work shifts from strident to poetic, with a gradual softening of his style and an expansion of his subject matter.” Of course this alleged breakthrough in the early 1990s coincides perfectly with Pettibon’s art-world entrée, with the moment he began regularly showing in commercial galleries. Now, that might be a simple case of causality; that, for example, the novel conditions of display and dissemination facilitated this sudden metamorphosis. On the other hand, it was also a period when the art market and art institutions got a taste for select comics, as evidenced in the elevation of R. Crumb, or the inclusion of a section devoted to comics in MoMA’s 1990 “High and Low” exhibition. And yet there is something fishy about this story of Pettibon’s maturation.

Sure, the work got bigger and looser, more colorful and painterly, but this acceptation of Pettibon’s early 1990s watershed creates a lopsided periodization in the typical presentation of his body of work. That’s certainly the case at the New Museum, where a few rooms are devoted exclusively to work from the 1980s, while the remainder of the eight-hundred-plus drawings were hung thematically according to Pettibon’s many frequently revisited motifs — superheroes, surfing, baseball, Gumby, Vavoom, Christianity, etc. Similarly, Homo Americanus, the catalogue produced for the 2016 retrospective at Deichtorhallen Hamburg, opens with ten more-or-less chronological chapters covering portions of his first decade — “Flyers (1979 to Early 1980s),” “Helter Skelter (Early 1980s),” “One-Liners (Mid-1980s)” — followed by seventeen undated thematic chapters — “Mushroom Cloud,” “Fire,” “Emasculation,” “Erection.” (Dates then reappear in the organization of the final few chapters, covering some recent experiments in technique and topical, political subject matter — “Iraq War (Since 2003),” “Projections (2010s).”) What we get is a historicized initial decade — the work emerging out of a specific time, place and social reality; changes tracked developmentally as the pictures inch ever closer to Art — while everything since appears in a long, unvarying present tense. This is not to say that, according to the standard version of Pettibon’s career, he made no progress after the great leap forward around 1990, but just that subsequent changes have been minor by comparison, subtle variations in the full bloom of a mature artist and less significant than the regular recurrence of Gumby.

Ray, I would have asked him if I’d had the chance, what do you think about the picture of you that emerges out of all these retrospectives, as an almost-artist making nonetheless iconic images who then becomes an artist around 1990. I imagine he would have countered with a different story, said, as he did in an interview with Grady Turner, that “Visually it has changed. That’s what they tell me. I don’t know if it’s gotten better or worse, but I didn’t start out with much anyway… But there was a point when, to my eyes, my work did become mature. In a way, it kind of happened overnight, in 1978.” Or he might have said, as he has elsewhere, that he was aware of the main currents in art in the 1970s but he wasn’t much interested in most of it, that he was, in the early days, more inspired by literature.

Buchloh, who has been Pettibon’s most committed commentator, has read the work beside the drawings of Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly and, in the New Museum catalogue, considers the zines against the tradition of political caricature of Honoré Daumier and Edward Fuchs. Although the essays are deft and learned, the appositions rely on distant reflections.

There is a nagging feeling that Pettibon’s drawings don’t fit neatly into any of the through lines of contemporary art history. His extraordinary productivity and obsessive revisiting of subjects perhaps gives him an uncomfortable resemblance to an outsider artist. Do these concerns in any way inform the choral insistence on his development into a master draftsman and colorist at the moment he quit the underground for the art world? Maybe not. But when we’re told that “his initial iconographies had merely mapped the banalities of the comics and the posed brutishness of film noir,” you can’t help but wonder whether the transformations in his work, the loose brushwork for instance, don’t do the same to art, which is more than capable of its own poses and banalities.

The other part of the story of Pettibon’s evolution concerns his tone: We are told that the punk sneer has softened, cynicism given way to a vast affective spectrum. Yet to me the caustic notes remain the loudest and clearest, the sarcastic reading always a compelling one, even — perhaps especially — in the most allegedly doe-eyed works. Those surfers dwarfed among towering waves: we can see them as pictures of the sublime, or equally as mockery of the search for transcendence. “And stand up tall! Straight,” reads the text beneath a slightly hunched surfer (No Title (And stand up…), 1998). “My road homewards lay through Waimea Bay,” reads another (No title (My road homewards…), 1995), a reference to a beach legendary in big-wave surfing in the 1950s. Maybe it’s a harmless caption, but I hear derisive laughter at the myth of finding yourself, your place, out in the waves. Carrion-Murayari wants us to see the baseball drawings as a reverent tribute the American pastime rather than caricature of the threadbare platitudes that surround the game, while lines like “Finally I reared back and heaved, struck the umpire in the face” (No Title (Calling my own…), 2013) or “When you fuck them, you feel cheered, restored to the community…” (No Title (When you fuck…), 1999), inscribed over figures of players in loose-fitting, old-timey uniforms, explicitly thematize the violence contained within our national myths, the violence that is the real American pastime.

Surfing, baseball, trains, Christianity — Pettibon’s obsessions are nearly all antiques. Even in the early days, he drew his subjects — apart from punks — from the subcultural and pop-cultural past: B movies and film noir, Vietnam, hippies, the Manson family, Jim Morrison’s dick. The seemingly infinite variations on themes amass into a kind of meta-historical iconography; they model a common vision of history, glimpsed through the obsessive repetition of received wisdom, the buildup of cliché. It’s history as banalization. The great exception to the rule of the antiquated figures and themes in Pettibon’s drawings has come with his searing treatment of political and military power, particularly America’s recent wars and wartime presidents, Bush and Obama. And this completes the picture: mundanities and cruelties. There’s your story of America in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. And what’s more punk than that? Right, Ray?