Moroccan-French artist Yto Barrada knits together family histories and broader sociopolitical narratives through works that employ photography, film, installation, sculpture, books, and hand-dyed textiles. “Moi je suis la langue et vous êtes les dents,” the current exhibition of Barrada’s work at the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon — an institution whose holdings include a rich selection of Islamic art within a larger collection of antiquities, European paintings, and decorative arts — underlines the artist’s interest in aspects of the Islamic tradition across a variety of media, as well as her critical assessment of Western strategies of appropriation during the colonial and postcolonial periods. These themes, as well of some of the works now on display in Lisbon, were also central to “The Dye Garden,” an exhibition held at the American Academy in Rome last year.

In both exhibitions, Barrada focuses on the construction of identity in the often-complicated aller-retour between France and the Maghreb, conditioned by family lore woven into and against official narratives linked to colonialism and its legacy. In Barrada’s 2011 film Hand-Me-Downs, for example, the artist used home movies from French colonial families in Morocco to illustrate the stories of her own family, a deft counterpoint between footage appropriated from strangers and the stories she had inherited via oral tradition. At the Gulbenkian, she revisits the work of French ethnologist Thérèse Rivière, who studied the Chaoui Berbers, an ethnic group from the Aurès Mountains in Algeria, between 1935 and 1936. Ethnology had been one of the means whereby French colonial agents, beginning in 1830 with the seizure of Algiers, identified and defused resistance. In fact, the first European ethnologists of the indigenous population in Algeria were French military officers, who paid special attention to the Berbers. Rivière was unique not only because she was a woman, but also because she allowed her subjects to express themselves independently in sketches, which she collected in her Album of North African Indigenous Drawings. Barrada recuperates Rivière’s research on the everyday lives of Chaoui Berber women and children, material that was either forgotten or erased in subsequent official narratives.

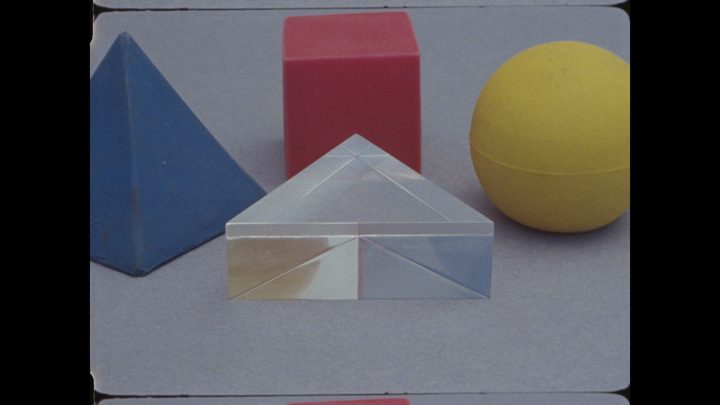

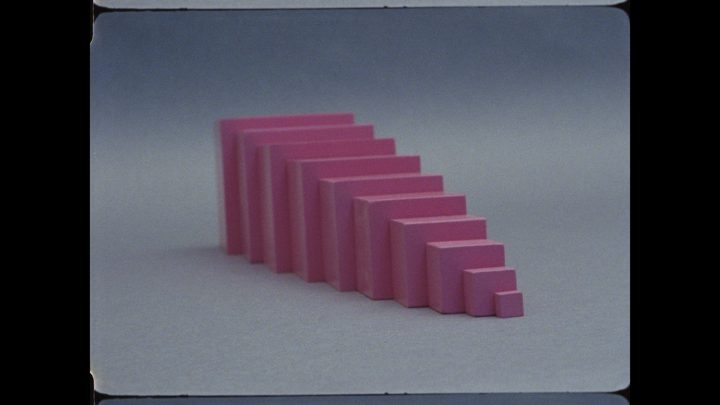

Perhaps what is most striking about Barrada’s work overall is the distinctiveness of her voice, even when someone else is speaking for her (or she is speaking through them): a choral approach steeped in history, privileging overlooked or silenced figures and episodes painstakingly unearthed through careful archival research. Her interest in Rivière’s contributions, which were eclipsed by those of other scholars, sheds light on how Barrada has attempted in much of her work to reframe colonial and postcolonial issues centered on the Maghreb in contemporary art. Unlike her contemporaries Neïl Beloufa and Adel Abdessemed, for example, who see recent history as a series of violent confrontations, many of Barrada’s projects highlight “women’s work” in the broadest sense, from handicrafts like sewing, quilting, and dyeing to the visionary pedagogical theories developed by Italian educator Maria Montessori. By broadcasting female voices, practices, and ideas, Barrada, far from insisting on any kind of simple dichotomy of gender, proposes a paradigm shift in a field in which the discourse remains dominated by men. Her subtle use of these sources is leavened by playfulness, a wry sense of humor, and an inventive use of children’s games and toys, the basic syntax of idea formation. The short film — and artist book — titled Tree Identification for Beginners (2017), commissioned for Performa 17 in New York, features Montessori toys, which stand in as proxies for the main protagonists. The artist locates them, along with drawing and play more generally, at the intersection of artistic preoccupations with form and transformation on the one hand, and the methodology of learning on the other.

This is not to say that Barrada shies away from politics. Quite the opposite: she has long investigated the gestures, vocabulary, and grammar of resistance to structures of power and control. “The central question remains,” she has stated, “disobedience and insurrection. How does one acquire and transmit political courage?”[1] She has an abiding interest in mechanisms of displacement and dislocation, including her own. All of these themes Barrada treats with humor and enigma. Tree Identification for Beginners, for example, revisits her mother Mounira Bouzid’s 1966 trip to the United States as part of a travel program sponsored by the U.S. State Department. Operation Crossroads Africa attempted to convince African students identified as future leaders “that the U.S. is a vital society worthy of sympathetic or at least serious consideration.”[2] But the turbulent summer of that year was the time of Pan-African, Tricontinental, Black Power, and anti-Vietnam war movements. Accompanying the rhythmically edited 16-mm stop-motion animation, the film’s voice-overs (many of which were read by members of the community at the American Academy in Rome), drawn from archival research, juxtapose Barrada’s mother’s stories of the summer with the organizers’ perspectives on the Africans’ attitudes toward this cross-cultural experiment, and other voices of this era.

Barrada’s interest in voices of resistance extends to the most elemental forms and conventions of language itself. Like many linguists, Barrada explores systems, including language acquisition and enunciation: lexicons, alphabets, figures of speech, slogans, methods of notation, mnemonic phrases, jeu de mots. Here, too, her family remains a fruitful point of reference. In Telephone Books (2010), currently on display in Lisbon, she highlights the notebooks of her grandmother, who, deprived of a formal education, invented her own language of mark making, including graphic symbols, glyphs, and diacritical marks, to identify and record her network of family contacts.

This extends to other languages and systems, including those pertaining to the natural sciences, which Barrada has mined in several projects. These include the 2015 book A Guide to Fossils for Forgers and Foreigners, a meditation upon Morocco and its complicated history, made up not only of sedimented accretions of geological fact, but accumulations of archival documents, glossaries, tourist clichés, unreliable sources, and falsifications. The book is addressed to a potential fossil forger, who, in order to hoodwink susceptible clients and expert paleontologists alike, masters the subject in all of its possible permutations. The result is an ingenious meditation on the nature of authenticity and the criteria used to verify it.

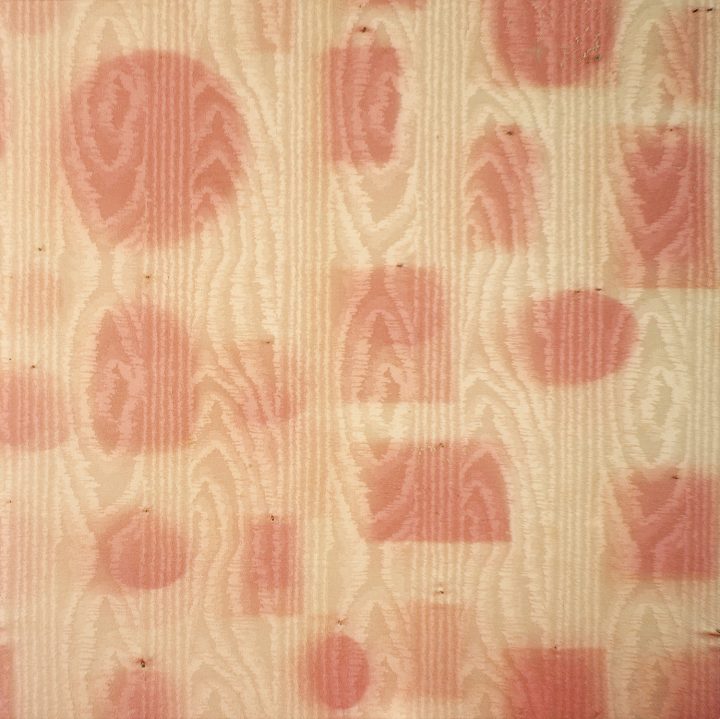

Long engaged with the botanical — palm trees, Tangier’s native irises, weeds, and the ragged edges of the urban landscape — Barrada has explored the foraging and extraction of natural pigments and the dyeing of fabric, an ancient tradition codified in the modern period by, among others, English textile designer and socialist activist William Morris in The Art of Dyeing (1889). Among Barrada’s upcoming projects is the creation of a dye garden in Tangier — in the same spirit as the garden laid out by Dada artist Hannah Höch in Germany — as an extension of her multidisciplinary community-building projects, which date back to her founding of the Tangier Cinematheque eleven years ago. Investigating natural dyes and horticulture, especially the tree identification in the title of her film, helped Barrada, too, as she adjusted to life in the United States after she moved to Brooklyn, New York, in 2011.

Displacement, or depaysment, animates these concerns. Adrienne Edwards has compared the plants and dyes used by Barrada in her recent work to a “language” in the place of those that “are not and ‘not not’ [hers].”[3] The fabrication of textiles, which the artist collects, and the dyes used to color them allow the artist to weave together the interests and anecdotes of her family — her grandmother was a talented embroiderer and her cousin a textile conservator — with intertwined colonial histories and vernacular practices. As is the case with many of her projects, Barrada’s investigation is exhaustive; she examines various weaving techniques, the fabrication of colors, the materials used to make dyes and where they come from, as well as the terminology associated with all aspects of the process. Natural dye production and the commercial networks it spawned thus provide an apt metaphor for the system of exchanges that shape identity in the colonial and postcolonial geography at the heart of Barrada’s work.

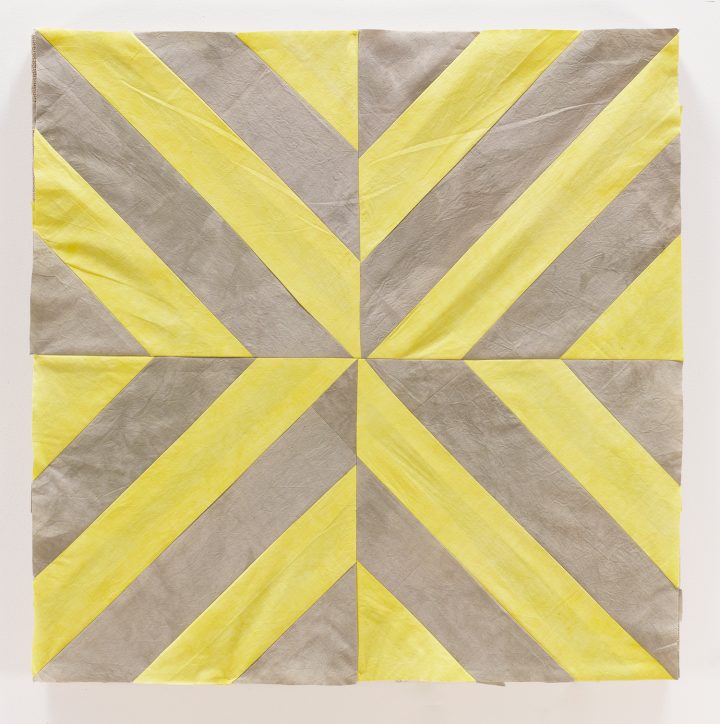

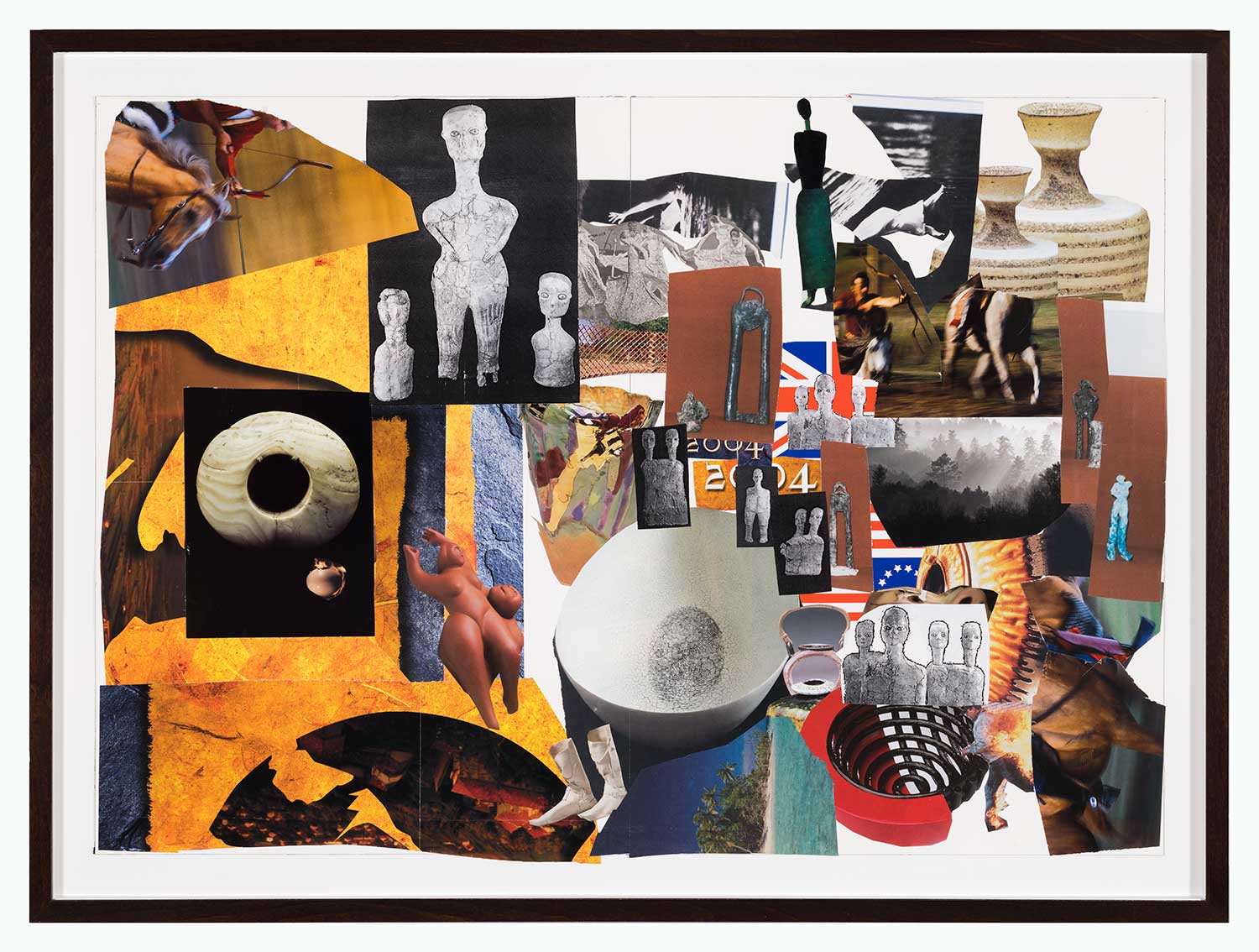

The new textile works shown at both the American Academy and at the Gulbenkian — designed and hand-dyed by Barrada — reference American artist Frank Stella’s series of fluorescent paintings from 1964–65, inspired in part by the Moroccan cities he visited on his honeymoon. Stella is one of many international artists who sought aesthetic inspiration and self-discovery in North Africa. These artistic epiphanies, lived out in the colonial and postcolonial space, have often been invoked to explain changes in the artists’ palettes, from those detected in Eugène Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger in 1834 to the infusion of light, pattern, and color in the canvases dating to Henri Matisse’s voyage to Tangier in 1912–13. Paul Klee’s experience in Tunisia, too, sparked the revelation, expressed in his diary, that “color possesses me… color and I are one. I am a painter.”[4] For a long time, Delacroix’s Moroccan notebooks and Klee’s testimony perpetuated the myth of the Western artist overwhelmed by the novel experience of the orient, one that unfolds entirely in the hermetic confines of an individual consciousness. This idea remained unchallenged when Robert Rauschenberg traveled to Morocco in 1953, where he gathered materials from antiquarian bookstalls that he incorporated into a series of collages mounted on shirt cardboard, a selection of which were exhibited in Rome. A hunter and gatherer herself, Barrada appreciates these kinds of appropriation, but she brings them firmly back down to earth.

In 1930, the French critic René Crevel, attempting to rally Klee to the aesthetic galaxy of the Surrealists, remarked, invoking another orientalist trope, that “some of his pictures seem woven in homage to the freshest visions of the Thousand and One Nights.” Crevel noticed that the texture and design of woven Persian carpets or the horizontal tiraz bands in Fatimid textiles, along with other assimilated elements from Islamic art, including Kufic calligraphy and motifs from illuminated manuscripts, provoked a reconfiguration of Klee’s formal syntax. Despite Klee’s insistence on the decisive encounter in Tunisia, this process was most likely well underway prior to his departure, thanks to the much-publicized exhibition of “Meisterwercken mohammedanischer kunst” held between May and October 1910 in Munich. In other words, Klee’s so-called breakthrough in Tunisia was preconditioned, even prescripted, not only by preexisting French orientalist tropes but by the artist’s close study of examples of Islamic art, particularly textiles, encountered in Germany before his voyage.

Stella’s modernist abstractions and their vibrant color indebted to his Moroccan sojourn must be seen in the same light. To prove this point, Barrada transposes them onto fabric using dyes made in her studio from plants, minerals, and insects. The results recall not only Stella’s compositions but the striped patterns in the costumes worn by Moroccan agricultural workers and those in works by painters Mohamed Chebaa, Farid Belkahia, and Mohammed Melehi, founders of the Casablanca School in the 1960s. These artists pioneered a North African modernist abstraction derived from the motifs and materials of popular, local art forms. Barrada thus undermines the notion of an artistic epiphany divorced from a local or historical context, resituating Stella’s work into a visual field that acknowledges the full extent of its debt to Morocco and its indigenous modernism. In putting Stella in his place, so to speak, Barrada also returns us to Klee and others like him, who plundered from the rich trove provided by a wide variety of Islamic art forms. If modernist mythologies underwrote an appropriation of those forms without acknowledging the full complexity of their origin, passing the transactions off as feats of individual genius, Barrada calls their bluff. The famously controlled lines of Stella’s compositions, a rational response to the Romantic and improvisational character of Abstract Expressionism, soften and waver in Barrada’s works, reflecting the deliberate irregularity of her handiwork. In the interlinked logic behind her work in a variety of media, Barrada engages abstraction, undermines colonial assumptions, unearths new grammars of resistance, and celebrates disobedience.

This essay is an excerpt from a text in the forthcoming catalogue of the exhibition “The Dye Garden,” edited by Peter Benson Miller and Helaine Posner and published by the Neuberger Museum of Art and the American Academy in Rome.