Alexander Ferrando: You typically offer no didactic interpretation of your shows. Yet you meticulously assemble the many disparate elements. What is your compositional process?

Ydessa Hendeles: I do not interpret my shows in essays because I do not develop a thesis or theme for an exhibition. I communicate by creating parallel worlds that viewers are invited to experience. However, because I compose shows from a variety of works and objects from different fields, I do provide “Notes” for each show. These contain all the information thoughtful viewers might need to move more easily beyond the literal object to a level of metaphor without being connoisseurs in the various disciplines of the pieces on display. I am a storyteller. Each object in a show contributes to the narrative, while also holding a place in the composition. Indeed, each object is an essential building block that bears no substitution. My approach is to start from the place, and then follow a site-specific artistic process to stage the art. My effort is to mediate between the exhibition space and the viewer to reveal multiple layers of meaning in the objects and something significant about the setting.

AF: Could you speak about the non-art objects included in your shows?

YH: When I make shows, I don’t discriminate between categories of object. I exhibit whatever I need to embody what comes from my response to and analysis of objects, in concert with my imagination. As a result, I start with an open mind, approaching everything as a curiosity — including contemporary art. If an element can summon a feeling, an insight or a metaphor for me — whether on its own or juxtaposed with other elements — I position it accordingly in an exhibition. I create contexts for viewers to have a contemporary-art experience. Even though pieces might be culled from the past, I display them as a means of talking about the present.

AF: What led to the founding of the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation in 1988?

YH: After eight years as a gallerist, I decided to forego the private-sector commercial side of my involvement and became a collector, but one who acquired art expressly for the purpose of making public exhibitions. I was responding to what I perceived as a need — in Canada for sure, but also in the world at that time. In 1988, collecting art and showing it was an act of philanthropy that supported artists. Establishing the foundation was a tangible statement of my commitment to the importance — indeed, the civilizing effect — of the contemporary art experience.

AF: In 2003 you curated “Partners” at Haus der Kunst in Munich. The show’s press release stated: “The exhibition was inspired by the history and architecture of the Haus der Kunst, the museum Adolf Hitler had built in 1937, to display the art he admired.” How did the works included in this show deal with the museum’s history and architecture?

YH: For the Haus der Kunst, I made a “curatorial composition” — my preferred term for my practice — with both art and artifacts that looked back to the history of the 20th century from the perspective of the turn of the millennium. “Partners” included works by a dozen contemporary artists in 16 large galleries. It also presented archival photographs, non-art objects and performances by an Elvis Presley impersonator from Berlin. Working with Paul Ludwig Troost’s original neo-classical architectural design effectively made a three-way partnership of him, his building and the elements I curated for the show. I restored much of the interior, treating the installation as a respectful refitting of a historical house rather than a reconfiguration of the architecture to suit the art. I intended it as an intervention that could offer an interpretation of both the space and the objects I chose to situate in it. The architecture commissioned by the National Socialist regime was made for art that was clear and certain. I made an installation of art that underlined the malleability of human identity and the fragility of human existence.

AF: Do you consider curating a medium?

YH: Yes, if the experience of a show proves comparable to that provided by an autonomous work of art and so long as the show doesn’t compromise the art displayed by projecting a personal or even a curatorial agenda onto it. There are many worthwhile approaches to curating. It does not need to be a “medium.” I support any approach resulting in a show that allows each work to speak with its own unique voice and leaves neither the artist nor the estate feeling violated.

AF: In addition to running the Foundation, you recently curated your first exhibition in New York for a private gallery and, as we speak, are working on a new show for a private gallery in Berlin.

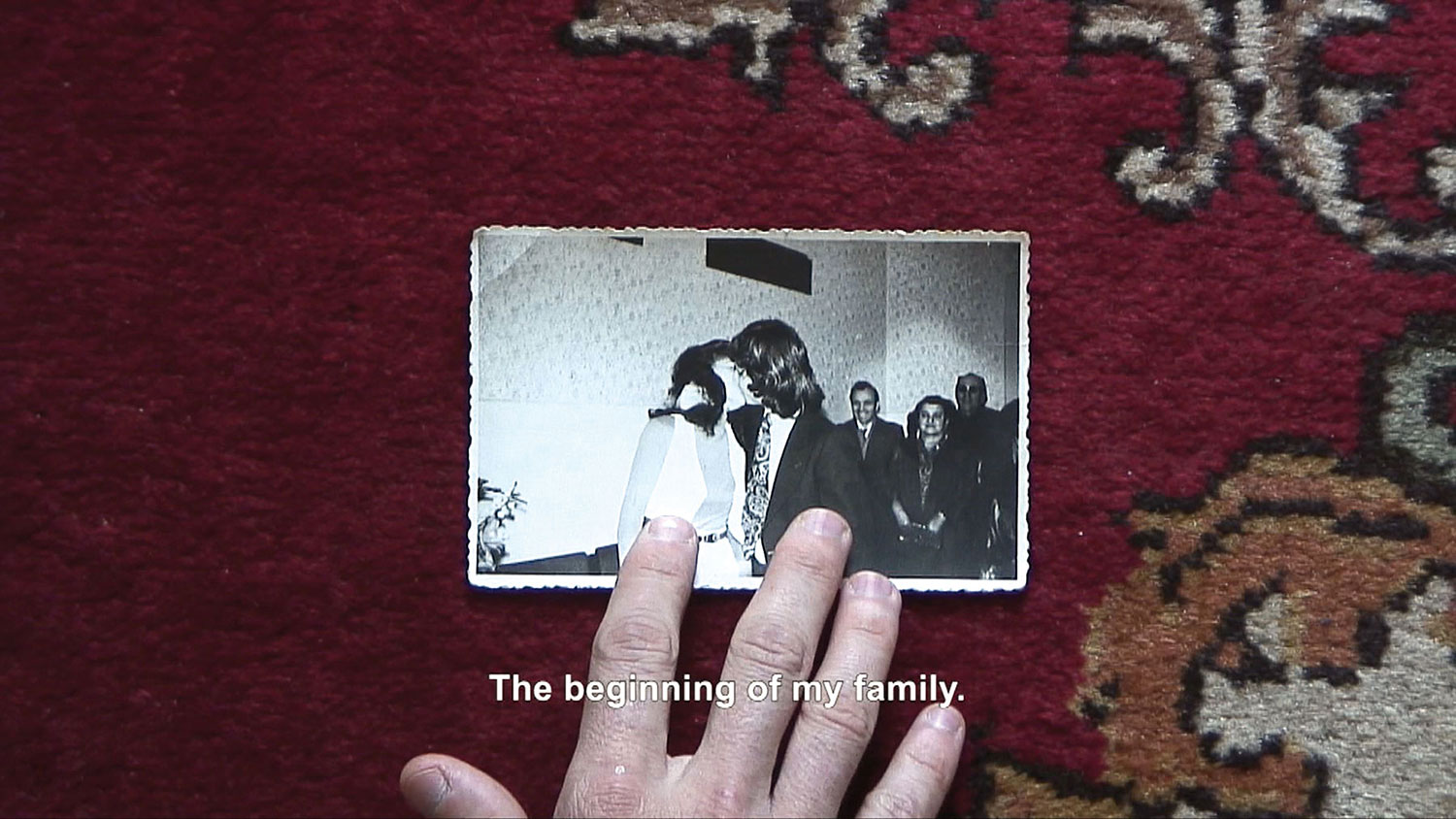

YH: I am an exhibition maker. I accept invitations wherever I feel I can illuminate a place — physically and in time. “The Wedding (The Walker Evans Polaroid Project)” at Andrea Rosen, featuring works by Roni Horn and Walker Evans alongside other photographic images and non-art objects, was a curatorial composition. The show at Johann König in Berlin, opening June 2, will mark my debut as an exhibition maker presenting solely my own works represented by a gallerist. This new show, “THE BIRD THAT MADE THE BREEZE TO BLOW,” is for me the start of a different kind of artistic interpretation.