The view from my bedroom window looks out onto a courtyard framed by a towering window-less wall. Some mornings, when Berlin’s winter sky breaks to forgive us with sunshine, the wall submits to deep shadows: smoke billowing from a chimney pot, a lattice that protects the drainpipe from leaves, a ladder leading up to the roof. These attendant shadows are strangely libidinal, somehow. Perhaps it’s the crisp contrast in light, or the commonplace shapes turned extraordinary, or the space from which I see them — my bed. Xinyi Cheng’s exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof — her first solo show in a museum, having been awarded the Baloise Art Prize in 2019 — reminds me of this mood: incidental moments of the everyday, loaded, hard to explain.

Take, for example, the lone photograph that opens the exhibition, which otherwise comprises around thirty paintings, from 2013 to the present. A man is depicted in bed, burrowed within a crumpled blanket; sheet having been eased off the mattress. Bright sunbeams cascade onto the wall, turning him holy with painterly light — distilling an otherwise slightly dank bedroom scene. We feel the ardor of the photographer’s gaze, which captures an instant of serene contemplation, seducing us to share in the sensuality of this light.

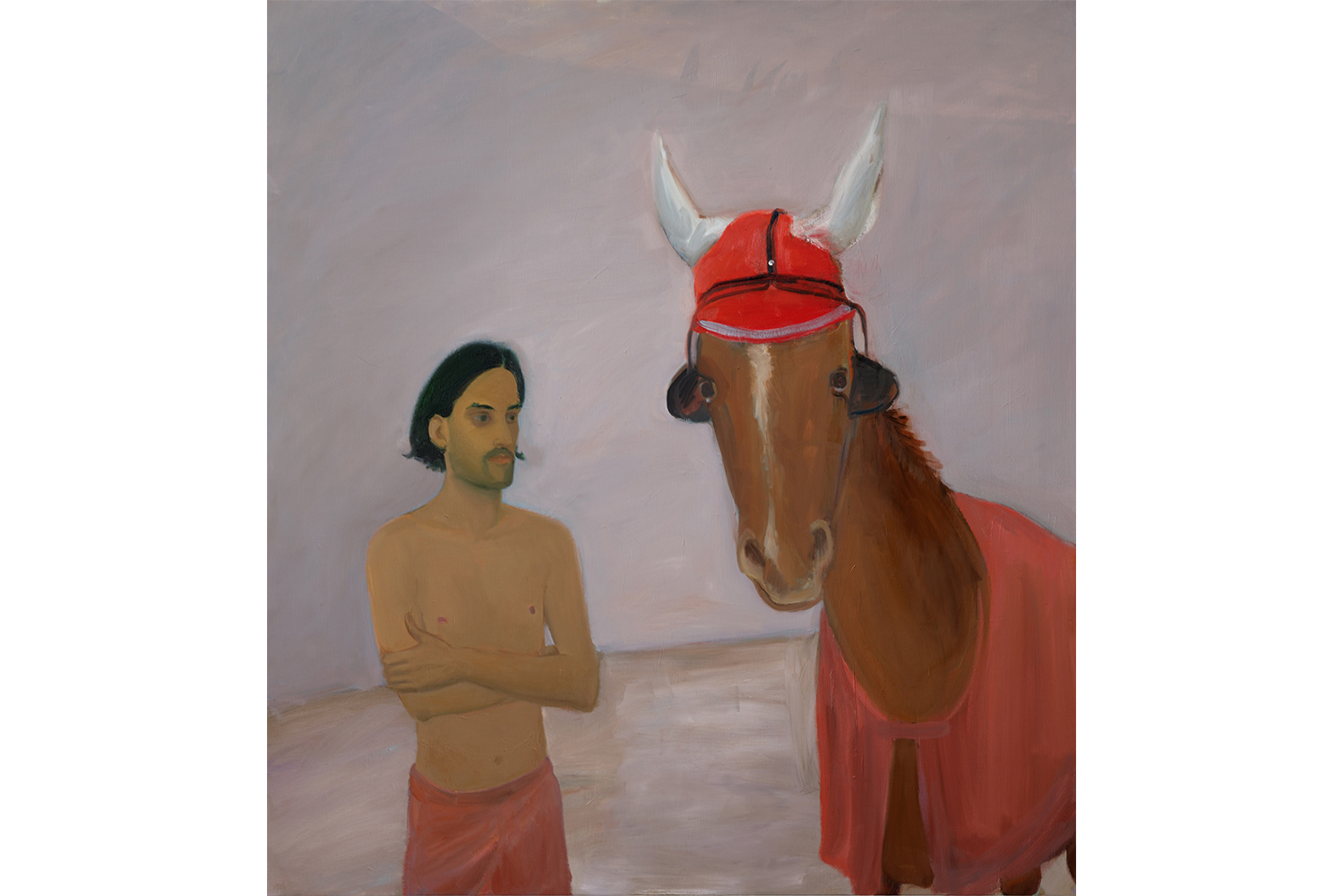

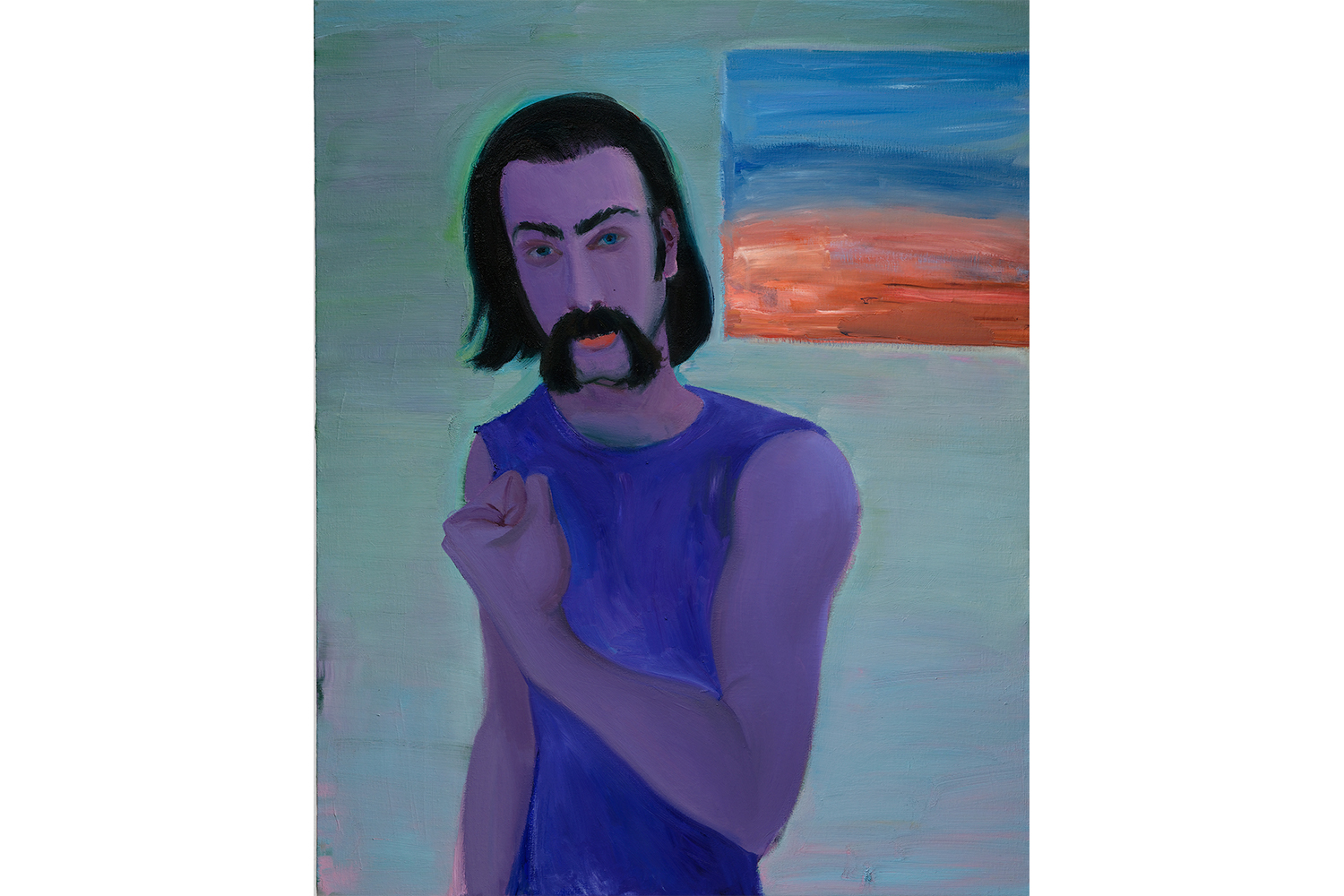

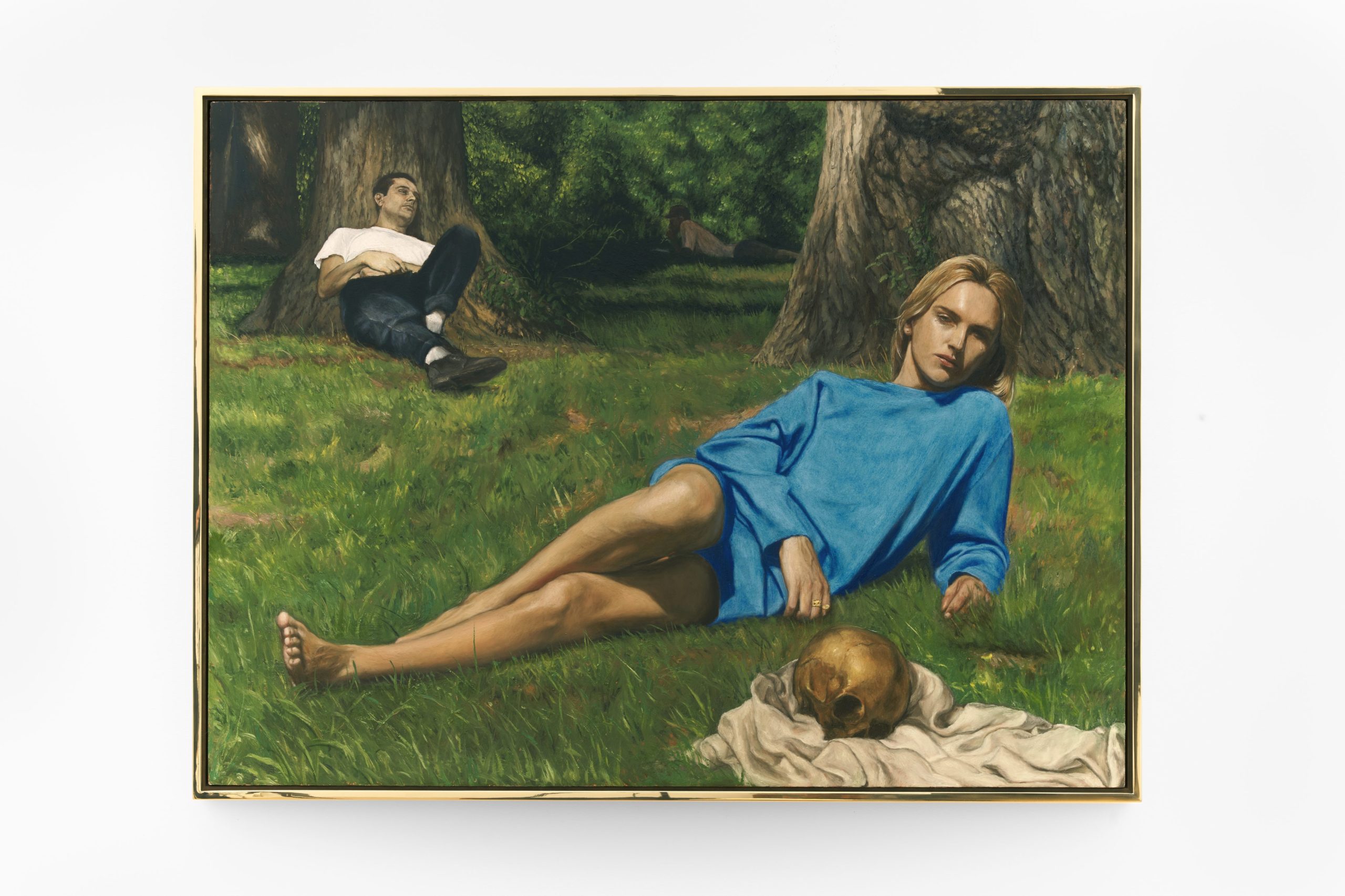

In the exhibition catalogue, Xinyi Cheng describes her paintings as being “about different aspects of desire and human relationships.” On the surface, this is seemingly paradoxical, given how she paints people: an opaque flatness defines their skin, a carefully rendered color field with only subtle tonal variations. Indeterminate or impenetrable, their smoothness is unnerving. This is skin that you want to push your fingers into, to check if it changes color, to leave a mark. These are not bodies glistening with sweat or heat or lust, but bodies quietly resting, looking, thinking, waiting. There is a certain pensiveness that simmers subcutaneously — which is palpable when observing the edges of Cheng’s canvases: thin applications of white, blue, green, and pink oil paint that have been gradually layered spill out, sloppily.

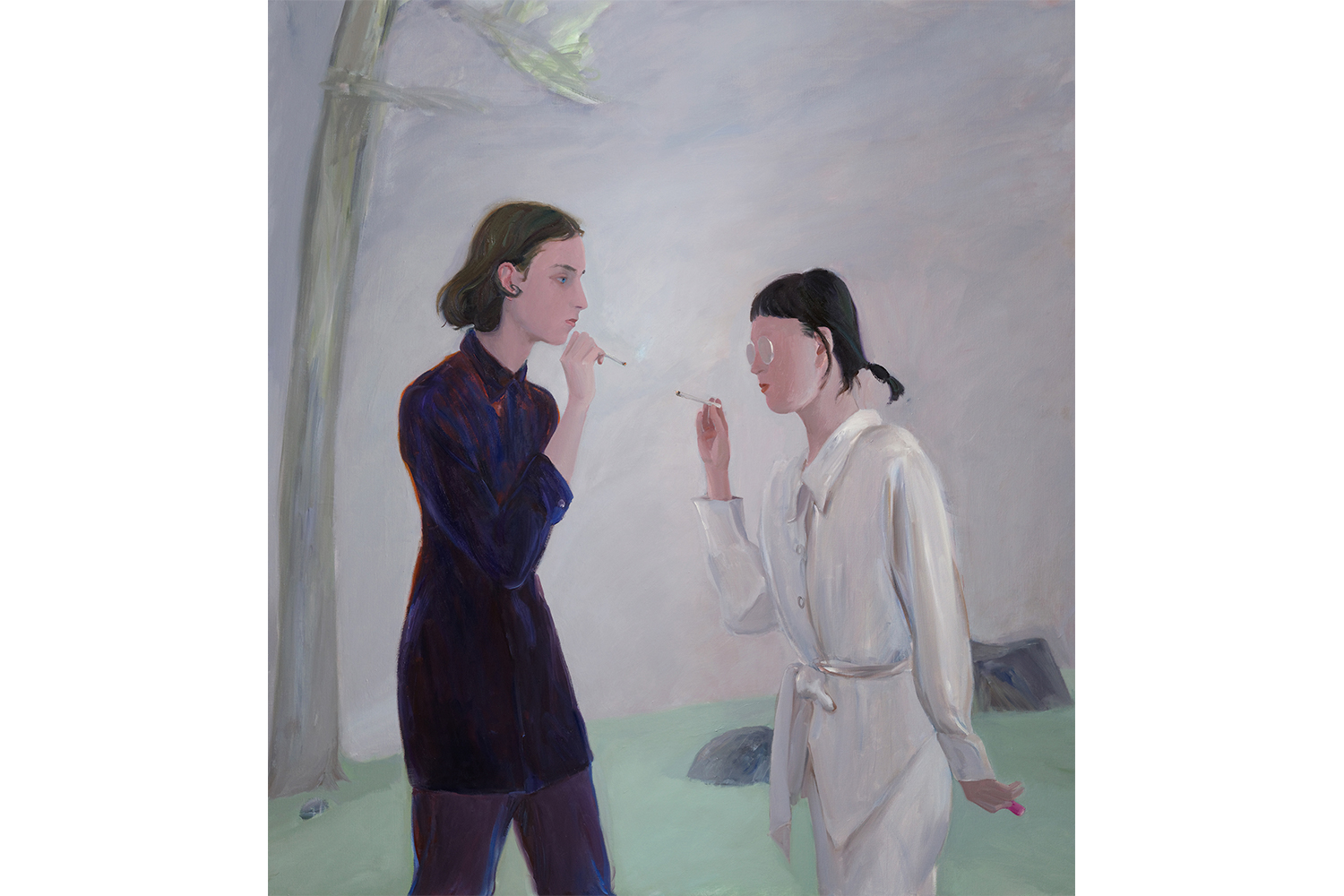

Cheng’s desire is one of subtlety, not easily given away. It is revealed only in details, like individual strands of tightly curled chest hairs (Crossing I, 2019), the glowing ember of a cigarette and the flame that illuminates someone’s cupped hands (Lighter, 2019), or the thick white smoke that leaves the intimate space of another’s lungs, blown past their lips, diffusing the secrets of their insides (Painting of Savva in the Light of a New Dawn, 2020). The smoking motif continues in For a Light II (2020), a work where two people inch ever closer to pass a spark between their cigarettes. One person, whose eyes are hidden by their spectacles, conceals a pink lighter. They attempt to break beyond reserve, sensitively seeking intimacy on a pale day. Such details capture the slightness that can fuel allure and the incidental textures that mark relationships.

The exhibition’s achronological hang emphasizes Cheng’s remarkable attention to color, which is deep, rich and dreamy, rhythmically dancing over the walls. Early works from 2013 — such as Bathtub, with its peachy pinks and pale greens, chromatic interactions that are reminiscent of Josef Albers’s nested squares — were made during a period experimenting with pastels and setting rules for a limited number of shades. The golden-mustard sofa of Incroyable (Monroe) (2019) is utterly sumptuous; yawning luxurious folds that are even more sensual than the naked body reclining upon them. Nonetheless, it is Cheng’s two black paintings that most appealingly smolder with hidden hues: Camp Fire (2020) is a tiny jewel-like square depicting a dark teapot heated at night over charred wood crackling with pyrolysis and combustion, while Camp Fire (2020) erupts just momentarily with a single lava-colored flame in the center of the composition.

Cheng’s paintings have a focused smoothness that intentionally keeps you at the surface, close-up, intimate. She too appeals to our haptic sensibilities; to toes that could be sucked (Itches, 2020); to flesh that could be savored (Smoked Turkey Leg, 2018); to fists that could been clenched, finally bringing about change for bodies out there in the world (Resolutions, 2020). Impulse. Justice.