Last November Wolfgang Tillmans released his first studio album, Moon in Earthlight, a fifty-three-minute-long soundscape that weaves together pop elements, ambient field recordings, voice, some techno beats, and studio jam sessions. There is the clicking of a traffic light in Nairobi, raindrops resonating on a metal gutter, and acoustically modified recordings of the artist’s heartbeat. Moon in Earthlight is a composition of eclectic music and sounds, harmonious albeit open to dissonance. The auditory scenario it creates has a highly cinematic quality, and, indeed, the visuals that accompany the nineteen tracks can be viewed in the mumok’s cinema. These sound-video elements seize ideas familiar from Tillmans’s photographic work: time frozen into still life, paper strips in movement, panoramic landscapes. The museum’s gallery exhibition is an equally cinematic, atmospheric, and dense compilation of works from the last decades. Displayed in a vast open space without any partitions, the more than 250 photographs sharply differ in format. Postcard-size prints hang next to huge ones; some are framed, while others are pinned directly to the wall. Tillmans’s unique installation practice reaches a new radicality here, emphasizing the physicality of the photograph as an object while highlighting the subjects that dominate his artistic practice. Portraits, views of bodies, images revealing Tillman’s longtime interest in astronomy, details of architecture, views of nature, as well as experiments with photography as a medium both glamorous and abstract, cover much of the white cube walls without overcrowding them. Some prints are attached to emergency exit doors. Others hang high up on the wall.

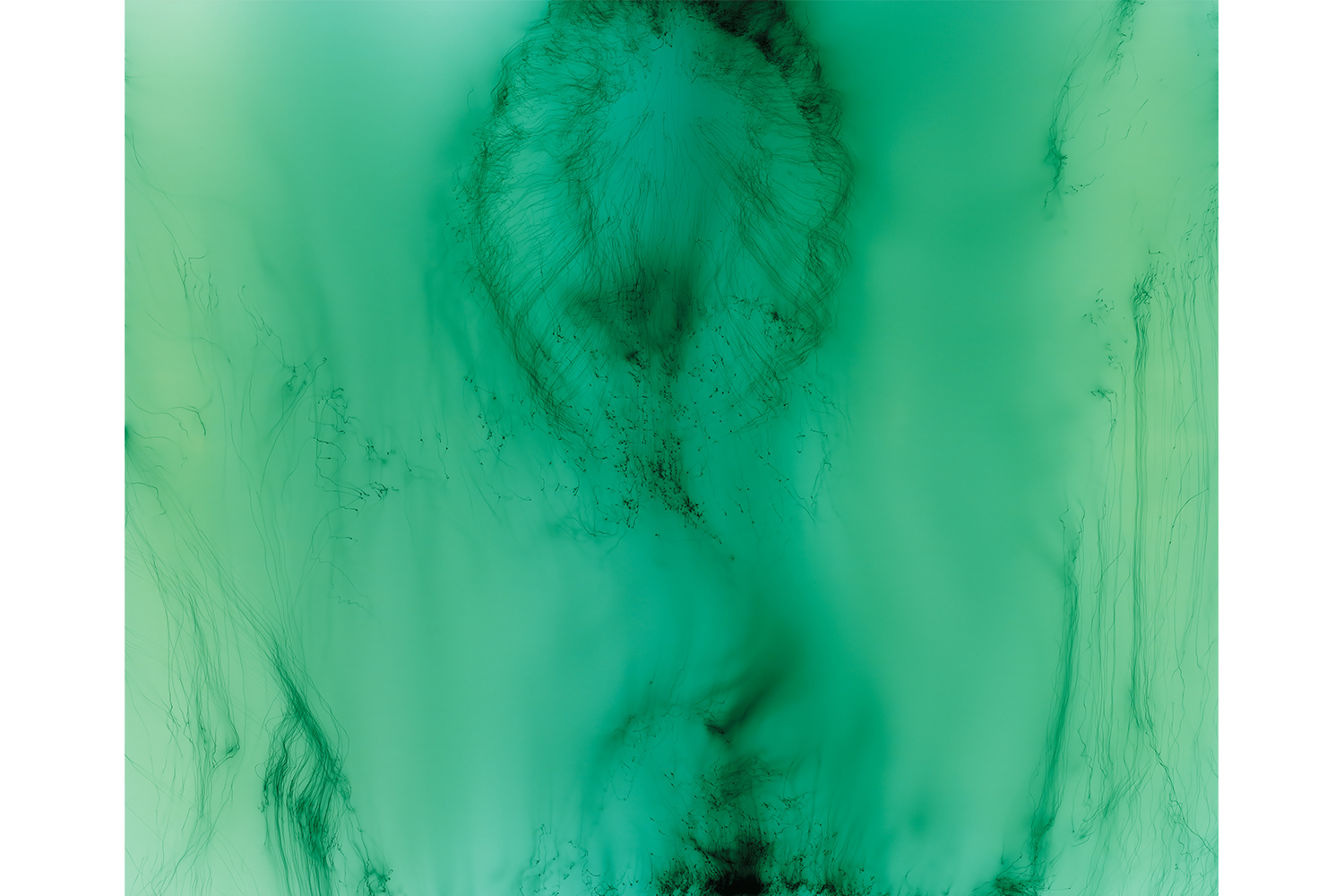

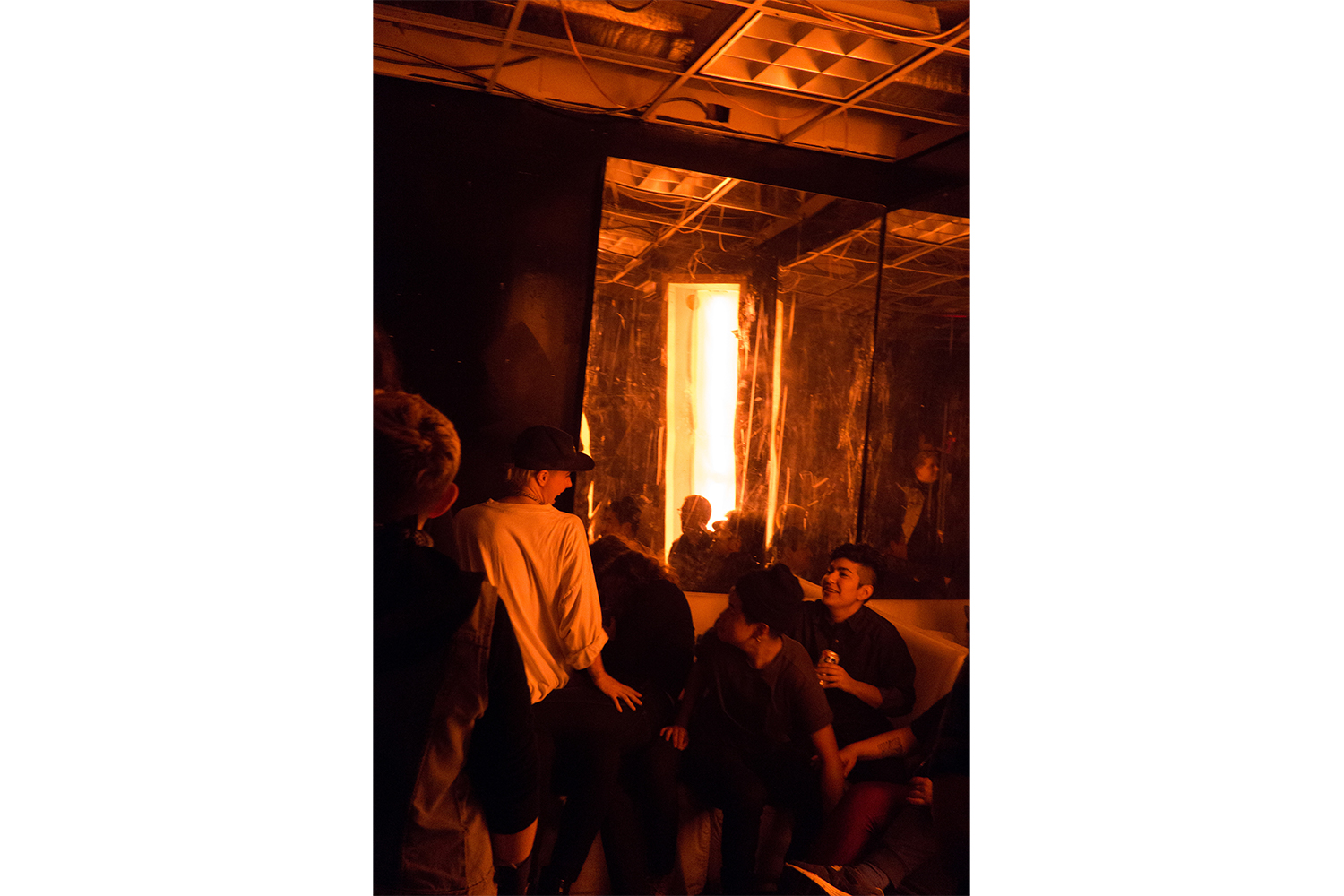

In its recontextualization of iconic classics, addition of new material, and changes of format or printing technique, “Sound is Liquid” unfolds in a manner reminiscent of a DJ set or remix. The works on display easily move between figuration and abstraction, with a focus on the aesthetics of the everyday. There seems to be no guiding principle — a large green abstract image (Freischwimmer 227, 2012) can hang next to a photo of bunk beds in a hostel in Australia (Gecko Lodge, Darwin, 2012) — yet everything in this spatial composition is coherent and in line with Tillmans’s signature style. Choreographing is a matter of rhythm and intuition rather than concept and chronology. But despite the homogenous heterogeneity this causes, viewers will find common threads. From his famous depictions of clubbing culture to recent portraits of artist friends, many works in this exhibition reflect the artist’s long fascination with electronic music, and even more so the social and political effects inscribed in it. Techno and underground in 1990s UK, with their then-new body politics, resonate like a soundtrack throughout much of Tillmans’s visual work. Music and togetherness are motifs in The Spectrum / Dagger (2014), a view of the eponymous New York club bathed in soft orange light, while images of global protests underline the importance of togetherness in forming a counter-hegemonic voice.

It comes as no surprise that the exhibition includes works on life during the pandemic that speak of a lack of such existential encounter. The most prominent one is called Lüneburg (self) (2020) and shows a smartphone leaning against a water bottle on the bedside table of a hospital. The sharpness of the image allows us to identify the person with the camera in the small speaker’s window as the artist, while his partner in communication remains invisible — the only other thing the phone’s screen shows is the fluffy heap of a pink blanket. The technical, social, and ontological status of the photographic image in the digital era align perfectly here. Generally, haptics have become more and more important for Tillmans over the years, and the exchange between body and gaze has moved to the center of attention. Walking through this exhibition, you get an almost physical sense of what that means.