Wolfgang Tillmans has been written about extensively, and it is almost alarming to see how writers project their ideas onto his work and define what he is about. It is tempting to do this, given the artist’s openness and generosity. At 38 years old, Tillmans is one of the most influential visual artists in the Western world today. His diarists’ approach presaged the advent of the MySpace universe. He is advancing unique photographic strategies marking the times we live in. He fundamentally understands how to maintain a personal logic and visual language by balancing a multiplicity of interests. He is very successful at suggesting new definitions by breaking down old ones and then almost building them back up. And he circumnavigates this tricky process with tenderness and compassion for humankind, a quality nowadays in short supply.

The current Tillmans survey exhibition at the UCLA Hammer Museum is a wonderful effort which the artist helped design and install. The curatorial staff headed by Russell Ferguson deserve great credit for their effort. While much of the work has been seen before (though not in Los Angeles) and written about, what is new are his abstractions and a version of the Truth Study Center. These works represent directions that point to possibilities and creative opportunities Tillmans could pursue further.

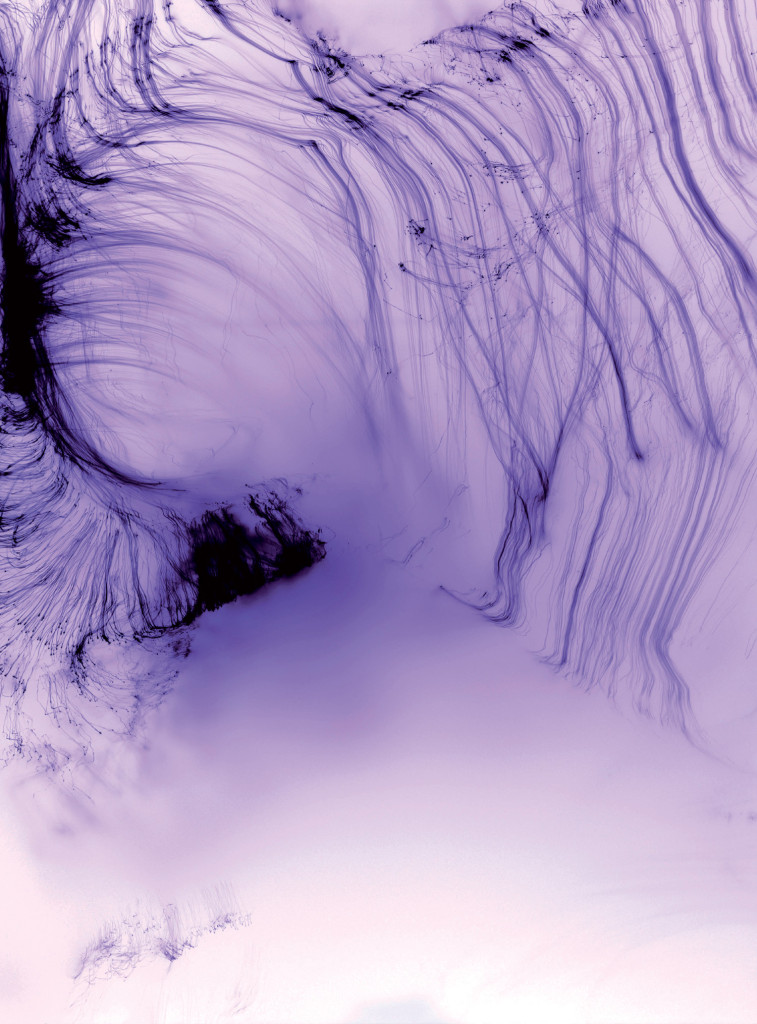

The abstractions are created by the direct manipulation of light on paper rather than through the camera. It’s only love, give it away from 2005 is a lush and large piece from the “Freischwimmer (Free Floating)” series. Though non-representational, the image resembles skin and hair, and images from his other series of abstractions also retain a literal quality. Yet the slight literalness of the imagery anchors them within the context of his overall project. The abstractions are arresting and evocative; Tillmans could go much further on this promising route if he chooses.

The Truth Study Center is an installation of photographs and image/text pieces arranged on top of a series of tables that knowingly becomes a didactic museum display. The choices are precise, yet the effect a bit oblique. The connections between photos and found information are not obvious. The selections from newspapers and magazines are topical, themed around the ills of war, racism, homophobia and social justice issues that liberal-minded persons are concerned with. Truth Study Center raises questions about the relativity of truth and suggests that every perspective is unique and individual. He contemplates authority and power in the ‘gray areas’ as a complex network of social relationships.

But can the democratization of imagery sometimes obscure what an artist could/should be saying? If Tillmans were more direct in this project, would we hear a stronger voice for the things he deeply cares about? The recent topical installations of Thomas Hirschhorn using found photos and information stands out as direct an approach as possible while still being incredibly effective.

Clearly opinionated and a deep thinker about the world around him, Tillmans understands a lot is at stake. Somewhere between the aesthetic poles of the Truth Study Center and the abstractions, Tillmans may already be updating the ‘balances’ that hold his remarkable body of work together.