I sat down with Wolf D. Prix in his office at the Vienna University of Technology, where knowledge is spread homogeneously and therefore, I suppose, knowledge and ideas are mass produced. No aim for vitae enhancement.

The following are excerpts from this conversation, translated from German.

Elias Bouyssy: What happened with Coop Himmelb(l)au in the 1990s?

Wolf dPrix: That’s when I returned to Vienna. I had to decide whether I should stay in Los Angeles or whether I should teach here at Die Angewandte (University of Applied Arts Vienna). Yes, that was a life decision. I decided to go back to Europe because my family was here, and we had more to do here than in America.

EB During this period, you also had this firm organization strategy called Eiger Nord.

WdP Yes, it was quite normal for “design architects” to team up with larger offices. Back then, I didn’t want to set up a large office. We weren’t bought up but established a partnership with ATP architects. That’s often the case — for example, Mies van der Rohe worked with a large office that played the executive architects — and that’s what we had in mind. We did one project together with the firm Eiger Nord in Dresden, inspired by Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler, mountaineers from South Tyrol and Austria who climbed the Eiger Nordwand in record time. Most people who climbed the Nordwand had to stay overnight, but they managed to ascend through because they took turns. The one who was better at rock climbing took the lead on the rock; the better ice climber took the lead in the ice, and that made them very fast. I once tried to walk in stairwells at the same speed they climbed. I have to say, they climbed the north face of the Eiger the way we climb stairs.

EB This organization allowed Coop Himmelb(l)au’s team to stay very small, right? I believe between seven to fourteen people.

WdP Yes, up to ten people.

EB Your work can be understood as a form of extreme authorship. I believe the Eiger Nord project put you in a position where you could work like a “permanently” emerging office in established fields, realizing massive projects. I suppose having a small team was important in that strategy.

WdP It was not so much a question of scale, because it was the size of a football team. It was more about how the team was organized. Back then, I was particularly fascinated by Pep Guardiola in Barcelona. Does this ring a bell? I think he’s the best coach there is, together with Jürgen Klopp. The other day, I read somewhere that the two of them really like each other. Anyway, I was fascinated by the fact that Guardiola took moves from other sports — ice hockey, basketball, and handball — and incorporated them into football. It’s extremely fascinating because if you only ever think about architecture, you only ever come up with architecture. That was our aim from the beginning: to expand the concept of architecture in language, theory, and building.

EB In this context, we are interested in your California houses, particularly the Open House and the D3-Tectonic House. You have often spoken publicly about the Open House’s client. This notion of authorial-empowerment was, I believe, very different in the case of the D3-Tectonic House.

WdP I don’t even remember what the process was like. The D3 (Tectonic) House came later than the Open House. The client was not as generous and understanding. The client of the Open House was a psychologist and appreciated the idea of the first surrealist project in architecture or the first deconstructivist one. Unfortunately, he died and the whole project was not realized. However, the steel components were sent from Austria to Los Angeles and part of it was exhibited at the Architectural Association in London on the way there. I say it was the first deconstructivist project, because it actually had a direct psychological connection with Jacques Derrida, who was influenced by Sigmund Freud. We tried to develop a new language by excluding the constraints. So, it goes back deep into psychology, something that is no longer considered at all today.

Today’s architecture is just building technology, where one thinks about everything except for the space you create and how it influences people. It’s about heating, ventilation — craft stuff, basically. For me, putting this aspect in the foreground is the most untalented thing one can do in architecture. You always have to develop that in a feedback system, and that’s the task we’ve always seen for ourselves. All our buildings need one third less energy than prescribed. And yes, that’s just normal.

EB We can see a development between these two Los Angeles projects. The Open House can be viewed as a case study of the American houses within a high Hollywood context, similar to Brian De Palma’s movie situation. The D3-Tectonic House is its deformation. It was actually the house where Stewart Burns, a producer and writer of The Simpsons, lived with his family.

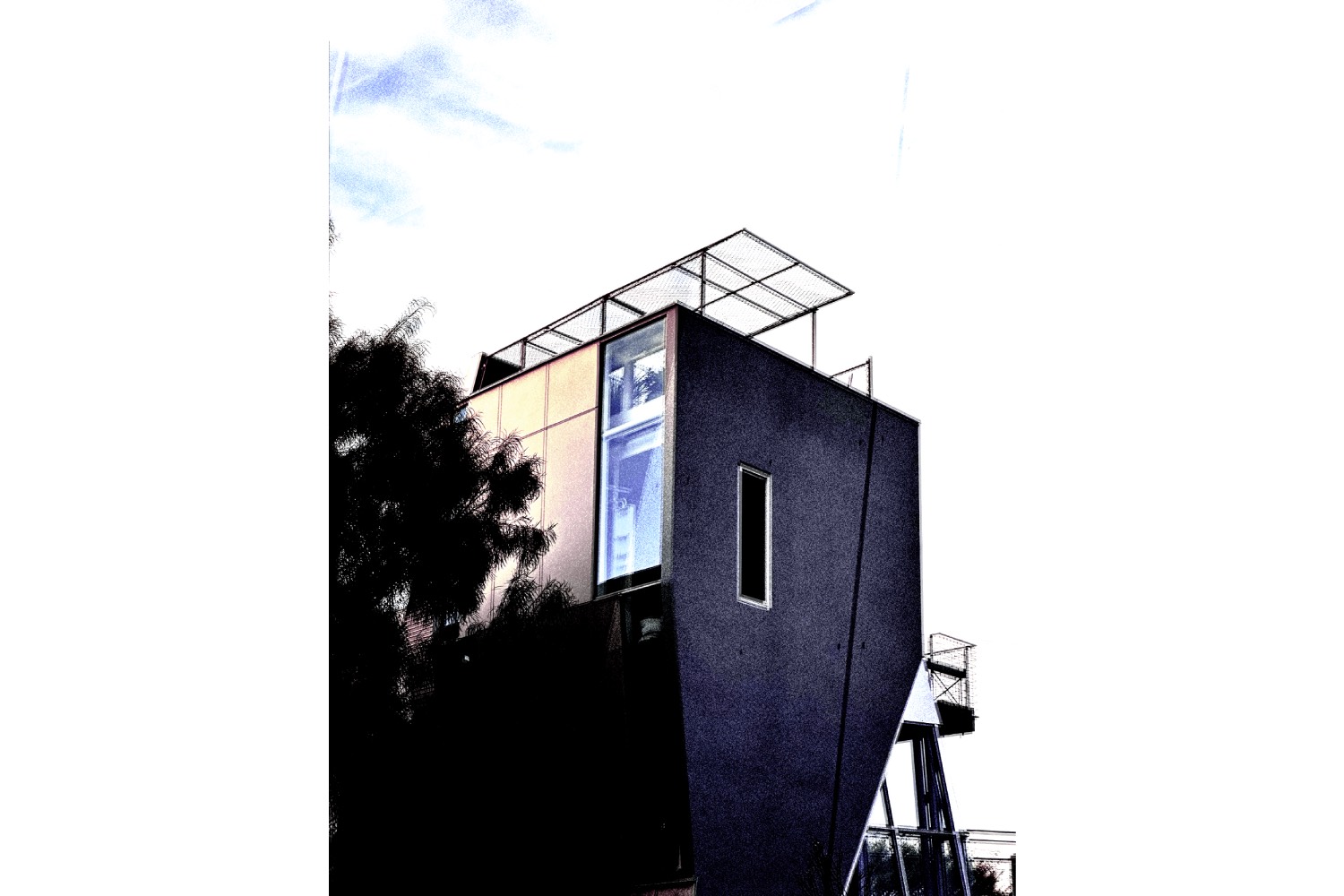

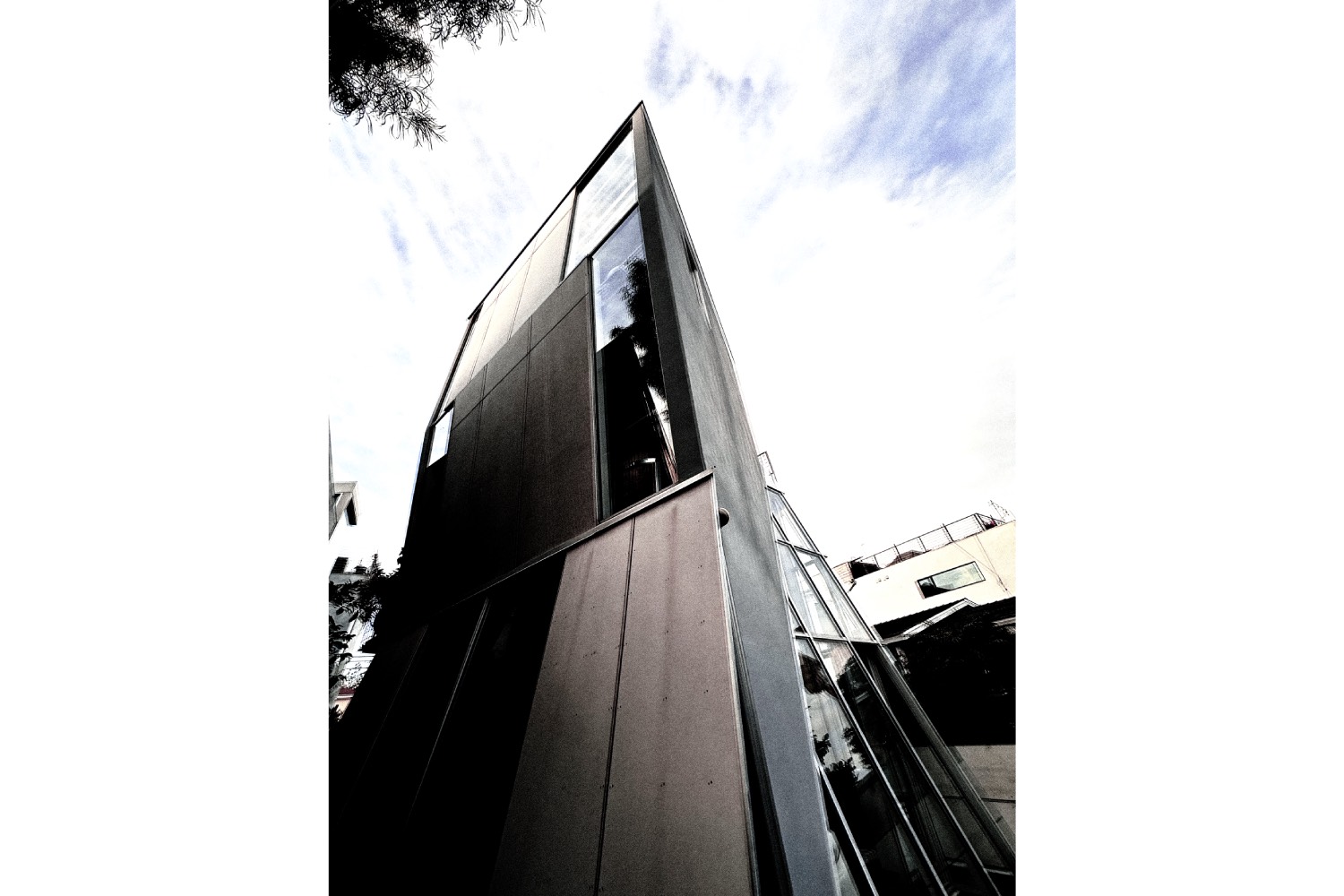

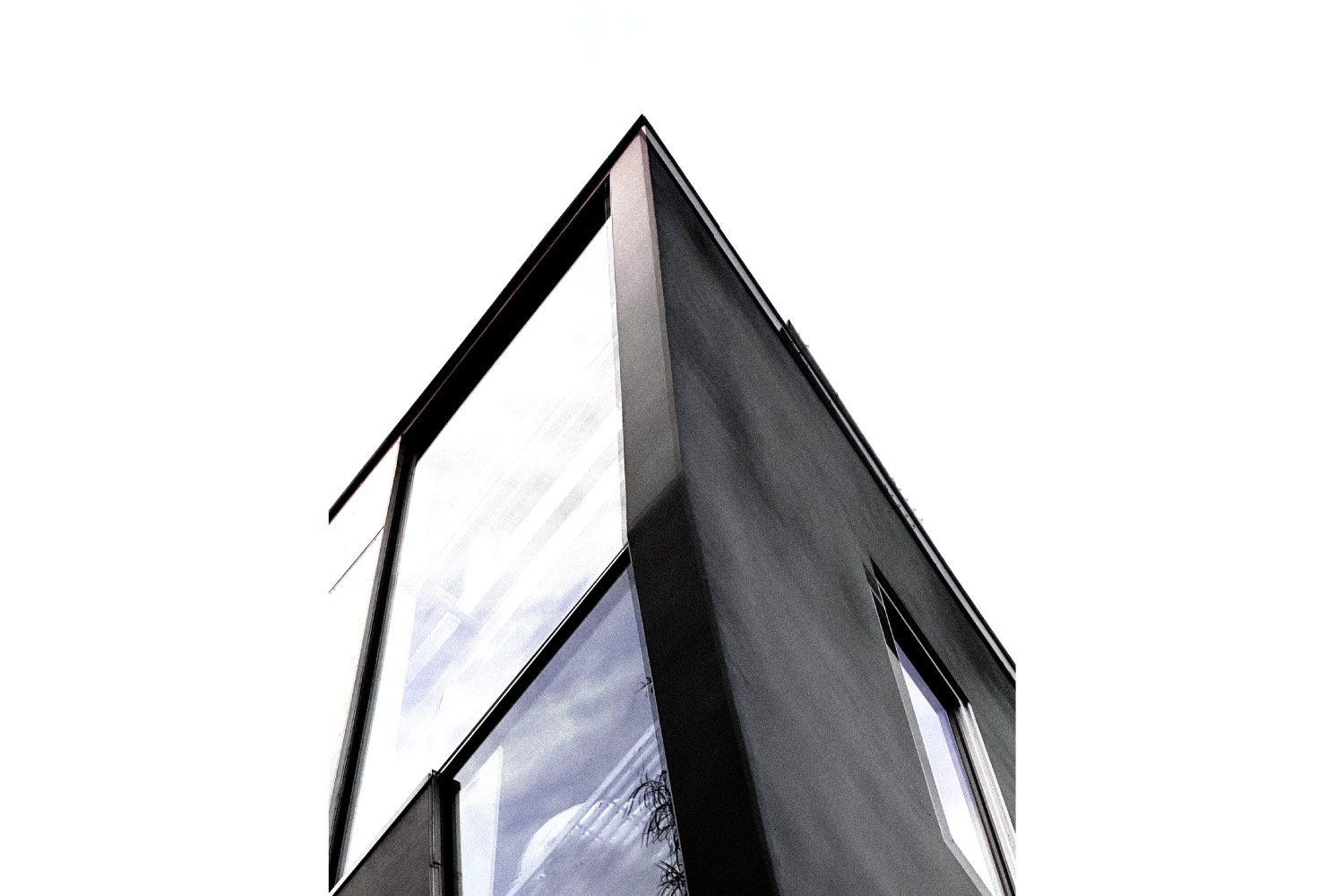

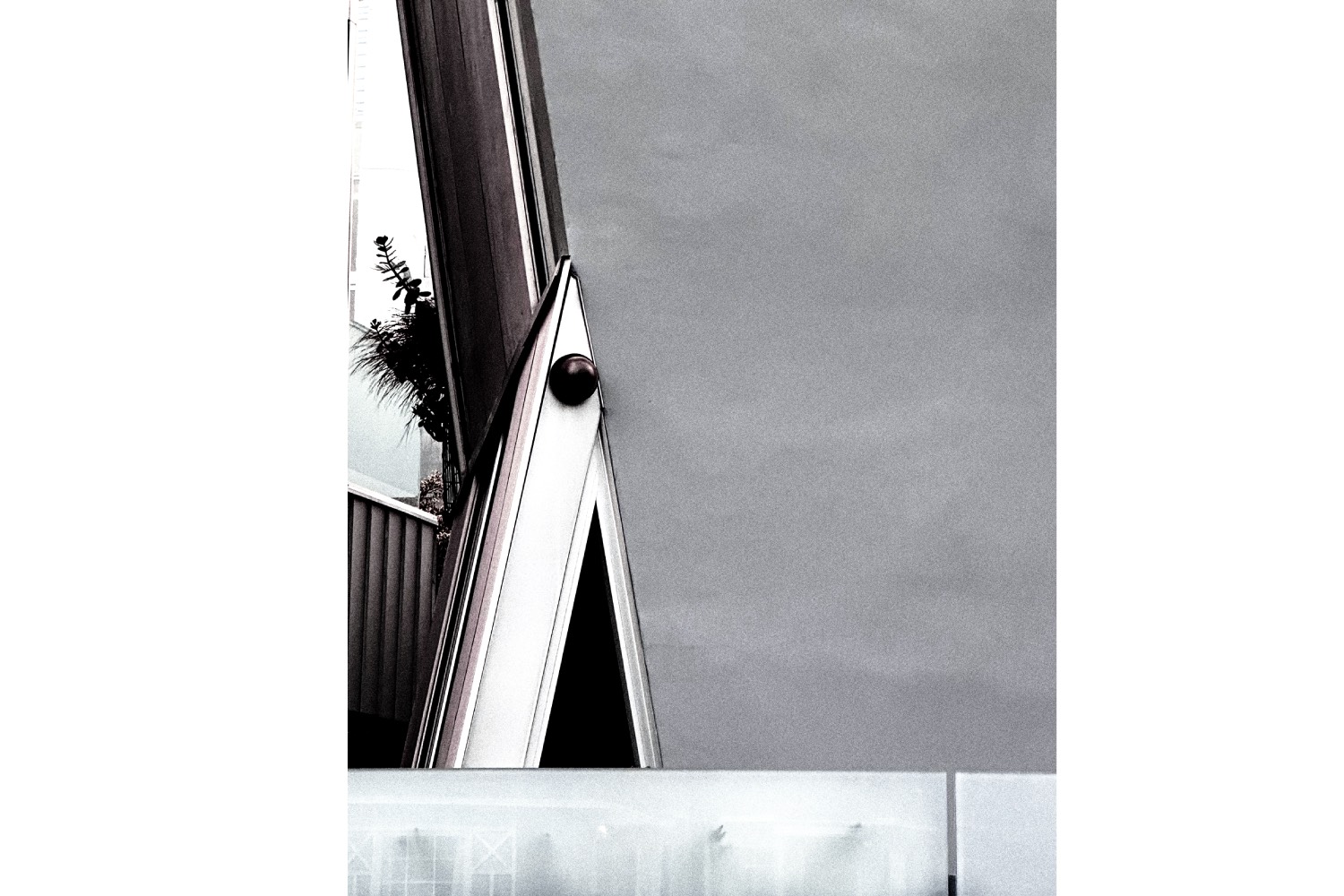

WdP That’s funny, I didn’t know he was living there. I don’t think Hollywood has much to do with it. We developed two or three houses in Los Angeles, and only one of them, the D3 (Tectonic) House, was built. We had a client who was from Germany, I believe. I had to go back to Europe and one of our employees finished building it. Yes, there’s not much more to say: it’s still a great house.

EB This interview will be part of the section called “cute-stalking,” essentially shadowgraphing buildings. So we are interested in this dimension of architectural image-production in your work. I want to talk about the Blazing Wing (1980), the project you did in Graz, for which you produced a video overlaid with rock music. I believe it to be one of the first examples of architectural click-bait. At that point, you were already working with visual-content production.

WdP Absolutely. That’s what we did with photography. Gerald Zugmann was one of the best architectural photographers. It took him four days to take a photo because he thought carefully about what he wanted to portray. We don’t use just any photographer; we choose ones who can convey certain things. Some aspects of a building can be captured, but the spatial connections? That’s not possible. When you capture a downhill ski race, you don’t know how steep the terrain really is.

EB The GoPro effect…

WdP Yes! But the point is, to judge whether I like a building or not, I need to have actually seen it.

EB How did the Blazing Wing come about?

WdP At the time, we were working on form mutations and started to deform plastic with flames. You can also see that in the roof of the Hot Flat project. To us, it was extremely interesting because we created a new design language manually. I don’t know whether it works just as well and can be just as imperfect when you generate it on a computer today. Of course, the computer can help grasping certain aspects more quickly. But grasping doesn’t just mean grasping (begreifen, in German), but also [holds Flash Art in hand] grasping (be-greifen). We always rely on the model to control a project, and by that I mean quick-models, no perfect ones. Obviously, we also do presentation models, where everything is solved, but in this case the model is built 1:1, and hardly anything changes.

EB I understand this work as a form of anti-professionalism.

WdP It has something to do with evolution and with mistakes in evolution. Mistakes are what drive evolution forward. And that’s why we say that there are coincidences when we build models when we draw. And these coincidences are what we develop further. We make a mistake, and then we think it through. Mistakes play a major role in nature; we don’t believe in them, but we develop details or materials from them, that’s how it happens. Not wanting to admit mistakes is an excuse for not-so-talented architects to fall back on rationality. As I said, evolution consists of mistakes — trial and error as people say. You try things out and see if they can prevail. The retreat to mathematics is an excuse for a lack of talent to develop forms without mathematics. So, they delegate it to machines. Obviously, you can easily develop any form, but new form only emerges through trial and error.

EB When you started to build more and to build bigger, did something change in your way of working, in the sense of forcing professionalism in your work?

WdP We are absolute professionals. Our museums have more visitors than other ones because they work well. To build something like this, you need various tools (hand models, computer models), the combination of which build up to a real BIM (building information modeling) plan.

EB I mean that architectural-professionalism (as a form of specialization/professional labor distinction) is becoming an important representative asset for architectural firms. I don’t see you presenting it, or at least not putting it in the foreground.

WdP We don’t need that. For us it’s about the built environment.