Andrea Bellini: In 1958, you started working with Yves Klein. Can you tell me an anecdote about him?

Willoughby Sharp: I first met Yves in January 1958. I was a twenty-one year old, deeply curious, trust-funded American art history student at the University of Paris. Having just returned form Düsseldorf where I visited the Alfred Schmela gallery (Klein had had a solo show there in May 1957), I was already familiar with his monochrome paintings. Even at this early date, I believe that I had a premonition of his preeminence and importance to my life. When I learned that he taught judo at the American Artists and Students Center on Boulevard Raspail where I took tea daily, I made my move. His classes were taught in the club’s basement on thick mats surrounding a large swimming pool. Yves, dressed in a blue-and-white, had just finished his class and was gathering his gear to go home. I introduced myself, saying that Schmela had shown me some of his works and that I wanted to see more. Then he invited me to his home/studio which was just around the corner at 14, Rue Campagne-Première. Yves was a strikingly handsome, highly imposing, energy-filled human being. Surrounded by his brilliant blue paintings and radiantly pigmented sculpture, isolated in an almost furniture-free, all chalk-white environment, he was animated and incandescent. Being with him in this special space which seem to exist apart from most of the material universe I had previously inhabited, I experienced a transcendent, life-transforming esthetic epiphany. Tragically, less than four years later, in1962, Yves died in that very place, on the same bed upon which we had sat discussing what he called “the immaterial, the indefinable in art.” As for an anecdote, I can tell you what Pierre Restany told me in a 1970 interview. He said: “Willoughby, if you really want to understand him and his work, you have to know that Yves Klein suffered from premature ejaculation.”

AB: I read in your biography that you befriended Marcel Duchamp in 1963.

WS: As an art history student at Brown University in the ’50s and then, starting in 1961, as a PhD graduate candidate with Dr. Meyer Schapiro, doing a dissertation on the early development of Kinetic art at Columbia University, I had already achieved a rather deep understanding of Duchamp’s paradigmatic importance to the development of 20th-century art. Marcel and I met in 1963 through the surrealist art critic, Nicolas Calas, who, three years earlier, had also introduced Duchamp to Rauschenberg and Johns. After moving back to New York in 1961, I reinserted myself into the then miniscule art world. Leo Castelli’s gallery at 4 East 77th Street (a few short blocks from where I lived) was the clubhouse-like hub of this tiny cultural community. I estimate it had fewer than one hundred members, most of whom shared at least a nodding acquaintanceship. At this pivotal time, in the beginning of the ’60s, Abstract expressionism was over. Pop art was gaining visibility. Warhol painted his first Campbell’s Soup Can in 1960 and Roy Lichtenstein had his first Castelli solo show in 1962. Marcel became interested in these artists. Pop, being more conceptual than Abstract expressionism, was intrinsically more interesting to him. And, in the very late ’50s, he became close friends with Rauschenberg and Johns. (They both bought works of Duchamp: Rauschenberg bought a signed replica of Duchamp’s Bottlerack in 1960 for $3.00!) Anyway, when Calas realized that I had not actually met Duchamp, he picked up his telephone and arranged to have us meet at Duchamp’s apartment. Duchamp lived with his second wife, Teeny, in a 19th-century, red-brick townhouse off 5th Avenue at 28 West 10th Street. Duchamp — the famous ‘éminence grise’ who many people thought dead until Walter Hopps curated his first American retrospective that year at the Pasadena Art Museum — greeted me at his front door, showed me a seat and slowly collapsed into the corduroy-covered, high-backed armchair that he had inherited from Max Ernst. Duchamp seemed tired and looked pale. (Later I learned that he was then recovering from a second prostate operation.) He crossed his long left leg over his right, resumed smoking his big, wet cigar and smiled me a welcome. Surrounding him hung masterpieces by Balthus, Matisse and Miró. In front of him on an antique table was a large, imposing chess set ready to engage anyone courageous enough to challenge him to a match. I was there on a mission. Duchamp was a judge for his close, long-time friend, William Copley, who awarded an annual art grant. I thought that my friend, Hans Haacke, one of whose waterworks I had brought to show Duchamp, might have a chance for this valuable prize. We engaged in some small talk about mutual acquaintances. I then lived in the Gramercy Park townhouse that had formally housed the art school of his friend Amédée Ozenfant, and the wife of his current New York dealer, Arne Ekstrom, was soon to be the god-mother of my only child, Saskia Sharp. He asked me to leave the Haacke for his consideration. When I returned about a week later to retrieve the work from Duchamp, the other French artist whom I had befriended, Yves Klein, was in my thoughts. It seemed to me that all three artists, Hans, Yves and Marcel, made art that engaged the mind more than the eye. Taking Haacke’s plastic, three-level condensation work back into my arms, I mumbled Yves Klein’s name. Duchamp misunderstood, thinking that I was referring to Franz Kline. I mentioned Yves’s blue monochromes. Duchamp understood my reference and, still smiling, energetically said in a very low voice that I had to strain to understand: “Art doesn’t interest me, artists interest me.”

AB: You met Joseph Beuys for the first time in 1958 and worked with him on about twenty projects. What was the most shocking thing he said or did in front of you?

WS: I worked with Joseph from when we met until when he died in 1986. With Joseph, there was no ‘wow moment.’ We shared a deep and lasting love. It was expressed when we met: we kissed on the mouth. He taught me (as he said): “Art and life are identical.” Of all the hundreds of artists that I have had the privilege of working with, Joseph is the one that I think of almost every day. Incidentally, New York’s Ronald Feldman Fine Arts has commissioned me to do a book devoted to the five-day visit here for his Public Dialogue contribution to my 1974 “Videoperformances” show.

AB: In 1966 you started curating and writing about Kinetic art. What sparked this interest?

WS: My understanding and appreciation of the work of Klein and Duchamp, and our friendships. But more than that, the energy embodied in early Kineticism. Many of those works — and my own electromagnetic nature — were complimentary, reciprocal. The dynamic attraction of that work was so strong that I was unable to resist becoming its proselyte.

AB: And so what happened?

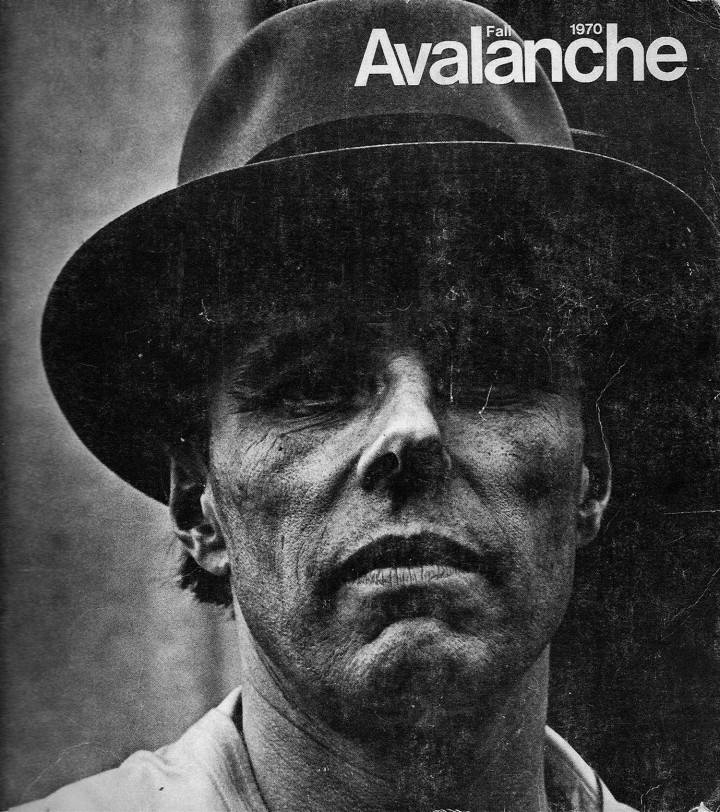

WS: I was a highly trained art historian who had just rejected two traditional career paths — teaching and museums. CUNY-Buffalo offered me the opportunity to teach two art movements that I had named, Kineticism and Luminism. At about the same time, in 1967-68, Alfred H. Barr and William Rubin wanted me at MoMA. I considered these options for several months and then rejected both job offers. Instead, I created two exhibitions, “Air Art” and “Kineticism: Systems Sculpture in Environmental Situations,” the latter for the 1968 Mexican Olympic Games. I say “created” rather than curated because I artrepreneured both these exhibitions. I chose all the artists. I executed their work from their instructions. When necessary, I supervised the fabrication of their works. I helped install their pieces. I wrote, designed and published the exhibition catalogues. And then did the public relations and arrangements to try to travel the exhibitions. (“Air Art” went to seven North American art institutions.) I think that Kineticism moved into Elementalism in the mid-’60s and that foreshadowed Earth art, post-studio sculpture and all the various forms of conceptualism. By the fall of 1968, I had accumulated an abundance of documentary material about this new art (letters, texts, photographs, slides, xeroxes, films, catalogues, etc.) I had also met a substantial number of extremely interesting artists in Europe and across America. From this, I saw that most of the significant art then being produced was not getting any curatorial exposure. Since I was an ‘independent curator’ who had published a number of professionally-produced catalogues, I thought that bringing out a magazine with this new, almost unknown work, would be a worthy undertaking. In this regard, two things happened in mid-November 1968: Tom Leavitt hired me to curate the “Earth Art” exhibition at Cornell University, and I met Liza Bear who became Avalanche’s editor. We dedicated Avalanche to the finest new art we could find. Who better to explain this work to our reading audience than the artists who made it?

AB: You published 13 issues of Avalanche, until 1976. Why did you stop? Were you bored?

WS: It is true that I was less engaged by the art I saw in the late ’70s. By 1976, Avalanche had dealt with much of the most interesting art and artists around at the time. I never was very interested in traditional painting and never gave it any space. I thought that I had accomplished my publishing aims: Earth art, bodyworks, post-studio sculpture, Conceptual art, performance and videoperformance had been established as the fountainheads of future art. Success ended any need for my continued work. Also, I should admit that making my own art was beginning to take command and that I wanted to devote myself more completely to my own work with video and the new telecommunications media.

AB: You also started producing “Videoviews,” a series of video dialogues with Avalanche artists (Acconci, Beuys, Burden, Nauman, etc.) Which interview do you consider to be the most important and why?

WS: I did my first Videoview in May 1970, six months before Avalanche was first published. It was with Bruce Nauman who I had previously interviewed for the cover article in Arts Magazine. Bruce was working on a V-shaped corridor piece at San Diego State College, and the College’s TV studio hired me to interview Bruce. From that auspicious start, the Videoviews have grown into one of my principal activities today. This year, my partner Pamela Seymour Smith and I will probably produce at least a dozen Videoviews. Two weeks ago, we shot Dennis Oppenheim (my third Videoview with him). And we are working to bring it out by Christmas as a DVD under the imprint of our new company sharp.smith. I suppose that my Nauman Videoview is the most important, largely because it remains to be issued as a DVD.

AB: How is it possible to see all the video interviews you’ve made since the ’60s?

WS: There is The Willoughby Sharp Archive in New York. As a body of work, the Videoviews have not been collected by any institution thus far. So it is not yet possible to see them in any one place. However, this year, Pamela and I were DAAD artists-in-residence in Berlin. Dr. Friedrich Meschede, Program Director at the DAAD, has expressed an interest in a Videoview exhibition. Ideally, we would like to show them in Berlin this spring and travel the show to the Venice Biennale.

AB: Since the ’60s you have been working with new technologies. Among your numerous projects is Two-Way Demo, the NASA-sponsored, satellite-delivered program linking artists in New York and San Francisco over cable TV (1977); the pre-Internet collaborative multicasts over telephone wires with artists using voice, slow-scan TV, facsimile and communicating computers over an eight-node North American network (1978); the computer project entitled Cancom which, at first, used Controlled Data’s Plato network of 16,000 users and then the I.P. Sharp PC-connected network (1978). Where does this interest in these types of communication technology come from? Which is the project you think has been the most important?

WS: I’m not sure of their source, but I can tell you when I first started to work with these media. Here’s a scoop yet to be published: In 1950, when I was fourteen years old growing up in Manhattan, I established a telephonic-based, interactive social networking service called Parties, Inc. It had elegant Tiffany & Company blue stationery with an engraved little telephone and my number: ATwater 9-9401. As an intensely engaged, high-society networker, I knew where all the New York holiday parties were being given. When my friends studying at out-of-town boarding schools returned for the holidays, they would call me to find out where the ‘hot’ debutante parties were being given. As ‘payment’ for my informational services, they told me about their parties. Consequently, I became “Mr. Parties Man.” In a real sense, I still continue this work, but now I use artistic information as my content. For almost three years (from 2001 to 2003), I published a weekly emailed listing of art openings to about 3,600 subscribers. It was an electronic publication called TSAR (The Sharp Art Report); when printed out, its last issue was 54 pages. The most important project was the collaborative, interactive, three-day transmission-art project, Two-Way Demo. My ‘integrator’ role in this project was (as they say in the telecommunications industry) to deliver the last mile. This means that my partner Duff Schweninger and I engineered the interconnect of the NASA-delivered two-way satellite signal into Manhattan cable’s upstream link to their satellite: we found and implemented an infrared transceiver that connected the two technologies — satellite and cable TV —making one continuously interconnected satellite-cable TV network. In effect, we networked the networks uniting them into one functioning telecom tool. Next September, 2007, we will be celebrating the 30th anniversary of this work about which we want to publish a modest book.

AB: You seem tireless. You are seventy and you are still working on numerous projects. Can you tell me something about the project The Videobook: Willoughby Sharp’s Oral Art History?

WS: High-octane energy and insatiable curiosity have always been my most faithful allies. On January 23, 2007, I will be 71. After a near-death bout with stage-4 throat cancer two years ago, my doctors say I could easily live another ten or twenty years. But I don’t conduct my life that way. I live like, “Today, I die.” So I am employing a double-life plan: Work as hard as I possibly can today so that my art will live tomorrow. This means full-speed ahead on my projected gallery/museum shows and continue working toward my career retrospective. It means finally finishing the autobiography that I have been working on longer than I want to say. And it means to continue learning about the teleculture and trying to understanding how it is affecting us.

The Videobook: Willoughby Sharp’s Oral Art History is a significant part of this work. Pamela and I began work on the Videobook in Berlin this year. So far, it consists of more than forty hours of videotaped personal recollections about all my various activities in the art world from the late ’50s to the present. The Videobook is intended to become primary source material for historians of postmodern art and contemporary culture. This interview has been a pleasure. If it stimulates your readers to know more, we can be reached at sharp.smith@earthlink.net