If things work out Genius’s way, in a (hopefully short, they say) while we’ll forget all about Genius. Because it will be so ubiquitous that we won’t think about it. We’ll forget that Genius started off as Rap Genius, a website dedicated to annotating and explicating the lyrics of hip-hop songs, and just use it for what it aims to be now: a platform to annotate anything on the internet. Last summer, Genius declared a new mission to “annotate the world.” In practice, it means that on any site, a user could type the prefix genius.it to any URL, and arrive at a page annotated by countless Genius users. Anything goes: from “this article’s title is misleading” to an explanation of the historical background of a given argument. And in the spirit of anything goes, slowly but surely, knowledge will be made. Flash Art contributor Orit Gat met with Tom Lehman (co-founder and CEO), Christopher Glazek (Executive Editor), and Emily Segal (Creative Director) in their Brooklyn offices to discuss where Genius is going and what the road there looks like.

Orit Gat: What made you join Genius? Christopher, you were working as a journalist, and Emily, you’re still part of K-HOLE, an art project-cum-trend-forecasting group. What made you interested in this project?

Christopher Glazek: I joined Genius mainly because I was interested in the ambition of the project to annotate the internet. I was interested in the possibility of this infrastructural change. We think that the internet is controlled by a few giant corporations — Apple, Facebook, Google — and that there may not be any room for another company. But what if actually there were a way to really change the game, to instigate a navigational change to the way everything is structured?

I graduated from college in 2007. After school I moved to Berlin. I didn’t think I was going do any of that online content stuff. My twenties were about meeting interesting people and engaging with the world intellectually. But the intellectual place a lot of people are arriving at now is what really matters. I was doing magazine writing, but I harbor no illusions — journalism is tough. In particular the kind of stuff that I want to do, long-form features for general interest magazines. There are a lot of reasons why that field is in trouble, but I was interested in what comes next, what is a different way of participating in media and intellectual culture, and also what is a crowdsourced way of doing that, which is crucial to what we’re doing here.

Emily Segal: Part of the reason I joined was that I was fascinated by Rap Genius as a company that seemed to be operating in the cultural space of tech in this really different way. I used screenshots from Rap Stats — which scrapes instances of word use from rap songs — and used them as data in a TEDx talk I gave. It fit into the way I was approaching cultural interpretation.

I was interested in the cultural and aesthetic space of the tech world. I love the idea of tapping into what the internet was supposed to do — it wasn’t supposed to be this jail/mall where content is all corporate, your data is stolen and everything is designed the same way. The idea that we could build a totally different kind of tech brand was appealing to me. Also, I wanted to be a woman in tech.

OG: So you were a Rap Genius user before. Tom, is she your ideal user? Who are your users? What do you know about them?

Tom Lehman: I didn’t know Emily until she interviewed, and after she did we were watching videos of her various talks and I stumbled upon the TEDx talk she’s referring to now and saw the Rap Stats. That seems relevant. We should probably do more of that kind of analysis with Rap Stats; that kind of macro level is interesting.

In terms of the type of user overall it’s pretty varied. The biggest product existing today, as opposed to the one we’re building, is the lyrics-focused destination website. It being a destination website is kind of an accident, since ideally we would like to take it to wherever music exists. That product is very much geared toward helping people deepen their understanding of lyrics and music in general, and so it is heavily driven by a smaller number of hardcore contributors. So similar to the way Wikipedia works, there’s between — depending on how you count — a thousand and ten thousand people who really drive the content production that millions of people are reading.

There’s another contingent of people who are using it, who are not the hardcore users as much but the artists themselves. That’s another core user base, which has been an interesting smattering: you’ve got Sia and Rick Rubin, but also people from across culture talking about other kinds of culture, so for example Michael Chabon annotated a Kendrick Lamar lyric. That was an interesting twist; you want to hear authors talk about their own work but you also want to hear them talk about the stuff that inspires them. The new thing we’re working on now is annotating the entire internet. The intent is for that to be a much more broadly used platform, so rather than a small number of people writing interpretations of culture and lyrics, have a large number of people reacting, criticizing and adding content to everything on the internet for the benefit of either just their friends — if you’re not an expert and you just want to say a joke that your friends will be interested in — or if you want to say something more insightful maybe other people will be interested in and if you’re a person who is particularly interesting because of your relationship to the text — you’re the subject of the piece, for example — then your annotations will be visible to even more people.

OG: What will those different levels of visibility look like? Barack Obama’s Wikipedia page may be the messiest page on the internet if it’s full of annotations. How do you decipher?

TL: We’re working on this right now. The basic idea is that when you show up to a page you’ll see a bunch of highlights, which is everyone who ever annotated it. The basic philosophical approach to this is to allow everyone to write whatever they want, not to censor stuff or have it fit certain guidelines, but to control what people see based on the quality of the contribution. So if you go to Obama’s Wikipedia page you won’t see everyone in the world’s annotations — maybe there’ll be a special junk drawer for that — but you would see annotations from people you know (people you follow on Twitter, people you follow on Genius, your Facebook friends) and from people who are specifically related to the piece in question, like Obama himself. Or there may be some people who are so famous and so relevant that their annotations are applicable no matter what their relation is to the piece. That is combined the notion of IQ on the site, which is points, reputation that you accrue by creating good annotations and getting upvoted. So a person who writes really insightful annotations will surface.

OG: What is the role of Genius editors in this world — between IQ points, Barack Obama and the junk drawer of the internet?

TL: Two things: the first is collaborative annotations written by the editors, which are supposed to represent the editorial community’s best attempt to interpret a line of poetry or music, and that will continue offsite. The editors also play a curatorial role, so if you write an annotation and an editor upvotes you, it is a great signal of the quality of your work because the editor is a trusted user.

ES: The other, more expanded way to think about the role of the editors is setting up editorial projects inviting people to annotate certain types of texts. So the editor isn’t just literally getting in on the annotation level but also creating the space and circumstances for certain groups of people to annotate particular texts.

OG: Is anyone ever paid to produce this kind of work for Genius?

CG: No one who isn’t on staff, full time.

OG: So they’re volunteers?

CG: The same way Wikipedia works.

OG: But Wikipedia is a nonprofit and Genius isn’t. There are a lot of conversations happening right now about free labor happening on the internet and I was wondering where you stand. Not because I think you need to pay people, but because you need to think about it.

CG: If people didn’t have fun annotating and didn’t want to do it, then Genius wouldn’t exist. But people do want to participate in this process. It’s a different way of conceiving of readership, too — people don’t get paid to read newspaper articles or to comment on them. The idea is that people aren’t interested in having pure editorial experiences anymore — the kind of glossy magazine piece that washes over you. They want to participate.

TL: There’s also a big element of the power of annotating. If you disagree with a review, for example, what better way to express that than write on the same platform on the same level as the reviewer, right there in the words themselves, not in a separate comment, free-speech zone.

OG: But you talk about Genius in terms of a knowledge project, and you describe knowledge in very Q-and-A terms. Here we’re talking about opinion rather than information. What role do these opinion annotations play?

TL: The hope is that knowledge will bubble up as an emergent phenomenon from thousands of different contributions of opinion. That out of a thousand annotations by one hundred people, the curation system I described will surface some of those good ones to the top. The idea is to get everyone on, really loosen the pickle jar, give everyone the ability to say what they want, and then let the good stuff float to the top. It’ll either be straight up knowledge or it might be an opinion that’s crafted in a way that’s eye-opening, even if not everyone is going to accept it as true.

OG: If you’re in the business of knowledge production online, what did you learn from Wikipedia?

TL: There’s a lot of positive stuff you can learn from Wikipedia. The biggest is that if you’re doing a collaborative knowledge project you need to have a very open perspective on it. Wikipedia started off as a closed community of experts rather than putting out something that wasn’t that great and improving upon it gradually. My favorite example is the first version of Wikipedia’s page for asphalt, which read, “Asphalt is a material for road coverings.” Then it evolves. There’s a sort of corollary to that which is the notion of Cunningham’s law: Ward Cunningham, who developed the first wiki, came up with the notion that if you want to find the answer to something on the internet, the best way of doing that is to post something you know is the wrong answer.

I expect that we’ll encounter the same kinds of issues Wikipedia encountered at first, which is that very few people trusted it and the quality in the very beginning wasn’t always good. Over time it gets better and better, because ironically the best gear toward quality is reducing the number of permissions — if more people can change something, that makes it better.

OG: So what would make Genius succeed? How would you be around in a decade?

TL: We’ve been working on it for five years, and from my perspective we’re not even close to the score zone. One thing to think about when talking about decades is that this company started not as a company but as an art project that was related to capturing the conversations that my friends and future cofounders and others were having about hip-hop, especially about me not understanding anything about hip-hop and being interested in learning a lot. I still think of it as an art project. But in order for an art project to last for decades and hopefully forever, it’s got to be a viable business.

One thing that’s going to come into play now that we’re shifting our focus to the “annotate the internet product” is that we’ll have to think about how the product could be truly universal. If this will survive for decades and be part of the fabric of the internet, we need to get people away from thinking, “Oh I’m going to go to Genius, I’m going to use Genius.” No: I’m just going to experience whatever I’m experiencing and Genius is going to be there for me when I want it.

ES: The lens through which you experience the internet, through which you experience culture, through which you read and write, that’s becoming part of the fabric of the internet.

OG: How do you frame this right now? How do you present this future presence on the internet?

ES: Well, that’s my job. I’m in charge of figuring out what our brand is in the world. I was brought in at the moment when we bought the genius.com domain, and now we’re foregrounding the fact that there are lots of other texts beyond just lyrics on the site, which has been true since the very beginning.

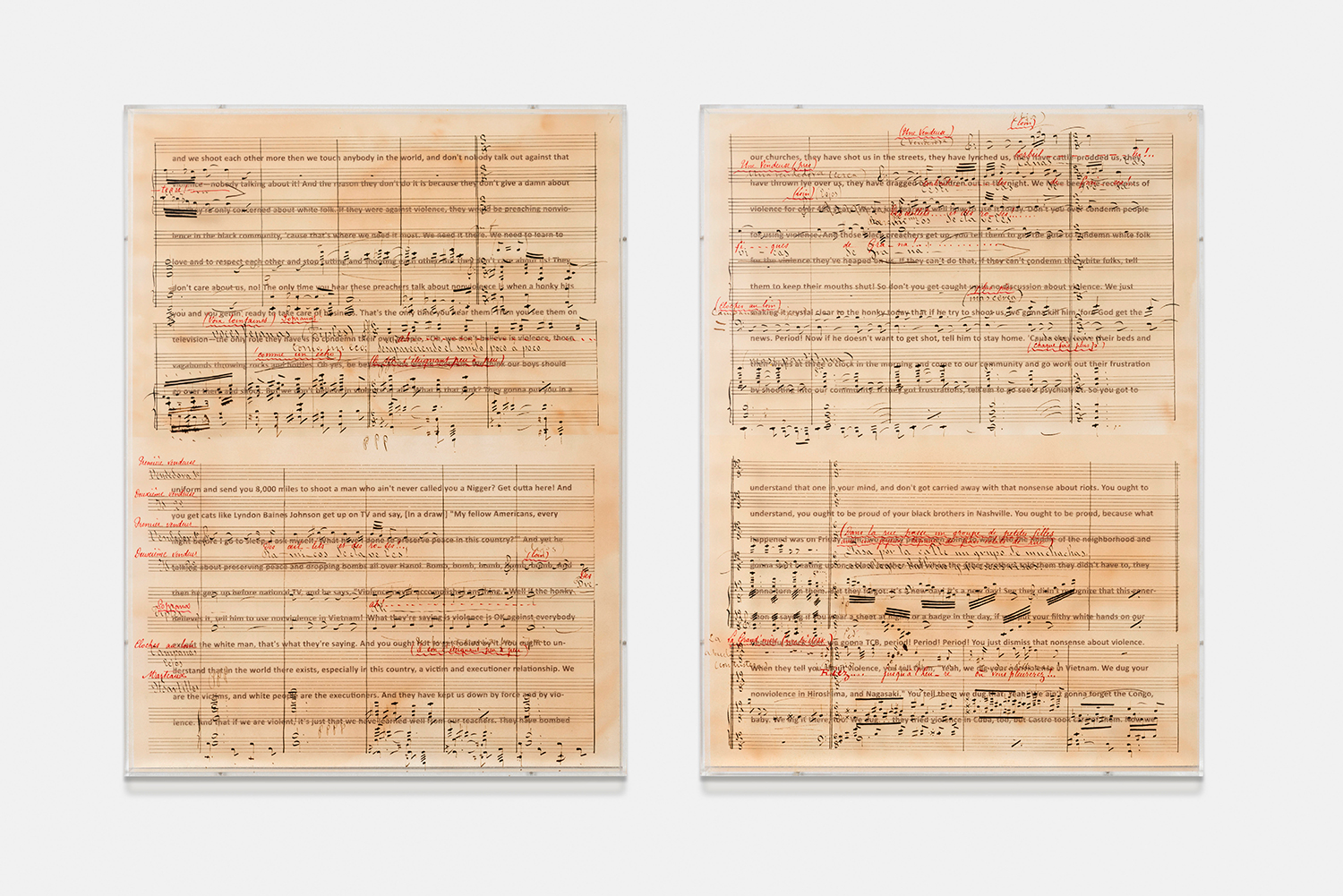

Lookwise, the brand hadn’t really changed and the mission to annotate the world hasn’t really been developed and put into existence visually. So my job is to figure out how this brand looks and talks and walks and quacks and runs and jumps. I want us to be the first internet brand that’s as advanced as any cultural brand. Everything on the internet looks the same — light blue, rounded edges, smiley, or, alternatively, old-timey, wooden, crafty. It doesn’t show the depth and breadth of the way people communicate or use knowledge. I think that Genius as a brand can stand for that type of position. We’re building a Wikipedia-style knowledge project with its roots in rap. That’s a really contemporary and unusual mission and situation. Aesthetically, I want to mirror those sides of the project.

OG: Part of the reason why Genius might succeed is that it’s coming out of culture — you’re starting off with a community that’s engaged with language and culture and how the two are intertwined. What will its relationship to this core community of art and culture be in the future?

TL: One thing I’d say is that we should definitely not think of Genius as a textual project. A lot of what we’re trying to do now is take the core text annotation thing and bring it to all sorts of content, all types of users. Ultimately, Genius is about media and culture broadly. It’s really our goal to be the meta commentary context annotation platform on top of all of that stuff. We should have a technology platform and the associated community rules and norms to allow a thousand people to converge just like they would on an Eminem or Kanye song onto a painting or a piece of contemporary art or a video and analyze portions of it with the same liveliness but also seriousness of the rest of the Genius project.

ES: I agree that visual media is a huge part of it — we’re not in a binary between text and image. It’s more about the idea of what makes us more interesting, what enlivens the conversation, what enriches it, and how do we create communities of people who know how to put it there.

Part of what I’ve been intrigued by is that artists have been some of the people most interested in the platform, because artists are interested in new technologies. It’s not necessarily about being able to annotate art so much as seeing what artists do with this new technology and how they interpret other forms of knowledge and how that might inform their art practice. Chris and I were talking about this recently: long-form journalists are not super curious about Genius. Artists are incredibly curious. You don’t have to convince most artists why a new technology might be interesting.