Curating the Whitney Biennial is a fool’s errand by design.

A snapshot of contemporary American art — a wide tent that grows every year — is nearly impossible: there is no monoculture (the internet killed that); no uniting political movement (even the most innocuous of statements can cause ire across the ideological spectrum); and no emergence of anything resembling an aesthetic “style” or monoculture (blame that on the Internet, too). The show will always be deemed too inclusive, too exclusive, not political enough, or too political. And yet, the Whitney Biennial’s mission of surveying the American artistic moment endures — and this time, yields surprisingly fantastic results.

Biennial curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli have titled this edition “Even Better Than the Real Thing.” The name and initial curatorial statement elicited groans with its artificial intelligence and alternative history artspeak. Yet, their curatorial mission is more complex upon review. Instead of relying on a single narrative of the moment, the seventy-four artists included in “Even Better Than the Real Thing” and its accompanying programming are allowed the space to showcase their own versions of the truth, creating a nuanced portrait of this country’s sociopolitical identity in which no one viewpoint is prioritized. By leaning into America’s chaos, Iles and Onli have organized an exemplary show, precisely by turning the weaknesses in the Whitney Biennial’s modus operandi into some of its greatest strengths.

Although inspired by participating artist Ligia Lewis’s idea of a “dissonant chorus,” this is the most harmonious edition of the Whitney Biennial in years. The wide, blank expanse of the Whitney’s four floors of galleries is transformed into a layout that feels spacious and dynamic through the inclusion of installation-like chambers throughout the show — gone is the overstuffed, salon-style feel of 2022’s discordant, claustrophobic edition. Artists’ works rarely overlap; but when they do, it feels as if these pieces were created to be in conversation. On the sixth floor, the works of Carolyn Lazard, Mary Kelly, and Sharon Hayes are placed together in a single gallery. Despite the differences in medium — assemblage, works on paper, and video — their work creates a meditation on the role of the physical body across generations and abilities.

Instead of feeling cloistered or separated, these individual rooms — often containing only a single work by a single artist or collective — feel monumental, both able to stand on their own as a total artistic statement and in concert with others. Nikita Gale’s TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME) (2023–24) is a showstopping reflection on the socioeconomic context of sound in the technological age via a single piano tapping along to a silent, unnamed song whose legal context is thrown into question via Gale’s interventions. Carmen Winant’s solemn, urgent archive of reproductive healthcare across the American South and Midwest, titled The last safe abortion (2023), unfurls across a single wall. Now an elegy to human rights with 2022’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, Winant takes images from university hospitals and library special collections that capture gynecologists, obstetricians, and nurses learning best practices for abortion care. Like Gale, the absence in Winant’s work — the patients — underlines the risk of the moment. The silences and purposeful redactions play off the airy exhibition design, allowing the audience to marinate in the blank spaces — perhaps a more emotionally effective and elegant way to highlight today’s ever-present brutality.

“Even Better Than the Real Thing” is at its strongest when it embraces a transhistorical vision of the present moment, seeing the narratives of the past as the key to understanding where we are now. Many times, this is explored through video and installation. Dala Nasser’s striking Adonis River (2023), an architectural work that mimics the ancient ruins of Qalaat Faqra in Lebanon, is sandwiched between three videos: Isaac Julien’s Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022), Ligia Lewis’s A Plot / A Scandal (2023), and Clarissa Tossin’s Mojo’q che b’ixan ri ixkanulab / Antes de que los volcanes canten / Before the Volcanoes Sing (2022). All these videos and their accompanying installations address international instances — despite their various geographic locations, ones that implicate the international and wide-ranging political machinations of the United States — of racial erasure in historical record, centering Black and indigenous perspectives as a means of reparation.

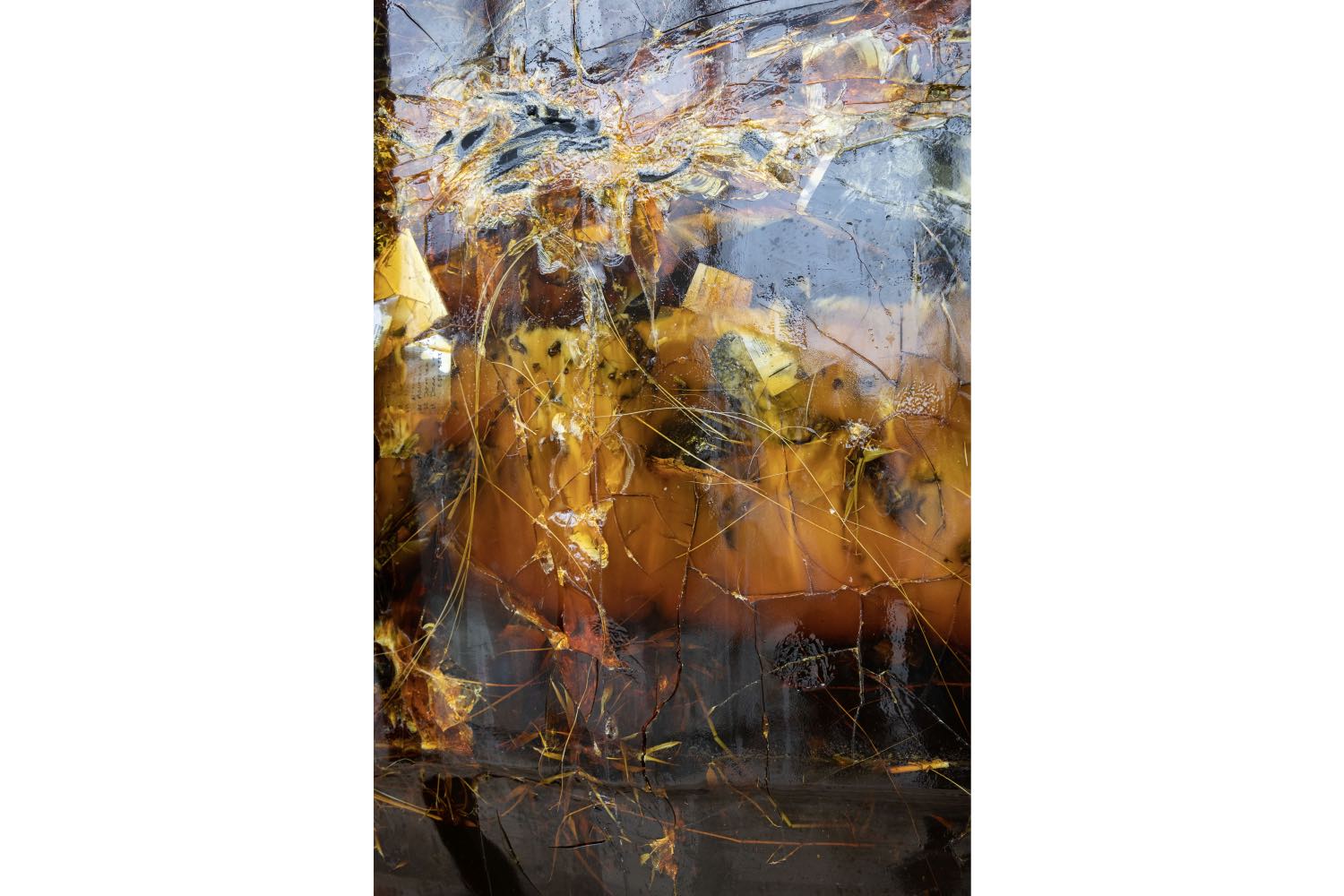

In keeping with this historical framework, many of the key placements in the exhibition are given to artists one would consider elder statesmen, such as Harmony Hammond and Pippa Garner. Their inclusion in the show makes the work of emerging artists referencing more traditional methods that much stronger: ektor garcia’s gestures toward the Pattern and Decoration Movement in his works cuprum (2024) and portal DF/NOLA (2021) gain a new vitality when hung on the same floor as Hammond’s Double Bandaged Quilt #3 (Vertical) (2020) and Suzanne Jackson’s ghostly, textile-adjacent forms; Maja Ruznic’s hazy paintings are all the more vibrant in conversation with those of veteran painter Mary Lovelace O’Neal’s gargantuan, vibrant canvases.

The show’s two grandest historical statements are installed with New York in full view. Kiyan Williams’s jaw-dropping Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House (2024) is installed on the Whitney’s terrace overlooking the excess of the Meatpacking District. The sculpture — made of only “earth, steel, and binder” according to its accompanying wall text — is an apocalyptic vision of a Greco-Roman temple that appears to be slowly sinking into the ground. With the American flag flying upside-down, this is an image of chaos and finality: no country outlasts its expiration date. On the Whitney’s western wall, Demian DinéYazhi’s we must stop imaging apocalypse/genocide + we must imagine liberation (2024) is a glittering work in neon. Like a beacon across the Hudson River below, the title is written in glowing script, but an extended look at the piece reveals that certain letters blink to spell out “FREE PALESTINE.” It is an important statement that, in addition to acknowledging a genocide many in the art world choose to strategically sidestep, supports the necessary opacity of the curators’ definition of America: the all-encompassing effect of this nation’s colonial power mandates that American art as we know it today reaches to the furthest geographical and sociopolitical margins. The immigrants, indigenous peoples, and all the others subject to our empire’s crushing power may have a better understanding of America than its own citizens. Perhaps the Whitney Biennial isn’t a futile gesture; it’s simply the biennial America deserves.