Polish art, I believe, operates in cycles — a bit like mania and depression in psychosis. And now is the time of depression.

Artur Żmijewski

To understand the changes occurring in Polish art today, one should look at it from the broadest perspective possible. When 20 years ago, on June 4th, 1989, Solidarity won the first partially free elections since the end of WWII, the tedious process of systemic transformation began. The radical shake-up of state structures connected with the introduction of democracy and a free-market economy had its impact on the cultural scene as well. After decades of isolationism, Polish art had not only to rebuild its own identity, but also to fill archaic institutions with new content, work out proper procedures, learn the intricacies of the free market and, above all, enter international circulation. Today there are all the indications to believe that it has succeeded in making up for the lost time.

One finds significant and justified the enthusiasm of critic and curator Paweł Leszkowicz who, in 2005, a year after Poland’s EU accession, wrote: “For the first time in my own career I read, write, and teach about Polish art with the same pleasure that I have so far about the foreign one. I clearly see a genuine explosion; finally the eyes and minds of artists and curators have opened. I’d call this phenomenon Young Polish Art (YPA).” And though the allusion to Young British Art was somewhat ironic here, it seems, the Polish art community did undoubtedly achieve success.

And yet the wave that carried Polish art for the last dozen or so years has just subsided.

We are in an “in-between” period, a time when the new has not fully emerged yet and the old still remains alive. And when the moods are not so high any more, there is still a lot to be done. What has actually happened?

It sometimes happens that defects only become visible when the dust that accompanies every construction project has settled. This is also the case with the Polish public (state budget-financed) artistic institutions. The frequent charges include salaries ten or more times lower than in the West, excessive red tape, inertia, an archaic management model and financial dependence on local political structures. And so it has turned out that, despite the vast changes, a work culture and customs rooted in the former system remain alive and well in Polish public institutions.

Barring a few examples, the institutions have no cohesive programs and curatorial clichés reign supreme. It seems that successes of Piotr Uklański, Wilhelm Sasnal or Monika Sosnowska have diminished our ability to see things just as they are. We thought that the whole of Polish art was strong, but when the artists mentioned above settled themselves in the art world, it turned out that structures of Polish art are only participating in their success, not having any by themselves.

On the other hand, now one could hear more about provincial institutions, such as Kronika in Bytom or BWA in Zielona Góra. What is more, in 2008, for the first time since 1989, three thoroughly new institutions concentrating only on modern and contemporary art opened: the Centre of Contemporary Art “Znaki czasu” in Toruń, WRO Art Center in Wrocław and the new venue of the Museum of Art in Łódź called “ms2”.

Adding to that, quite new standards are to be developed by the Museum of Modern Art being created in Warsaw (WMMA), whose opening is planned however only for 2014. Meanwhile, the WMMA team is whetting the appetites by organizing in a temporary space small but important exhibitions (of, for example, Alina Szapocznikow). As I write this, it appears that on June 21st, on Paweł Althamer’s initiative, the Park of Sculpture, coordinated by WMMA, is to be opened. In the park situated in the Warsaw district called Bródno we will find projects by Paweł Althamer, Monika Sosnowska and Olafur Eliasson.

The institutional crisis that we are witnessing is both a symptom and a consequence. It is a symptom because Polish art has found itself in a new, global context, and a Polish artist does not have to launch his/her career in Poland. This is something new, because the main architects of the recent successes of Polish art in the last decade or so, people born in the late ’60s or ’70s, not only started their careers in Poland, but had to reform established institutions or build up their own from scratch and learn the intricacies of the global art scene by themselves. Meanwhile the new generation, which no longer remembers communism, has both the institutions and the knowledge. A sign of the times is the career of Tomasz Kowalski, a young painter (born 1984) who, even before completing his studies, signed a contract with Berlin’s Carlier Gebauer gallery. This is exactly the opposite of the career paths of the artists of the previous generation, who have lived all their professional life in Poland.

But the weakness of public institutions is also a result. Namely, the result of the repositioning to classical positions of two private-owned Warsaw galleries, Raster and Foksal Gallery Foundation (FGF). Without a doubt, both have been places of crucial significance for Polish art in recent years. Artists represented by them include (apart from those mentioned above): Ołowska, Kuśmirowski, Żmijewski, Simon, Budny, Bodzianowski, Bujnowski, Maciejowski, Grzeszykowska, Libera…

Both Raster and FGF are truly phenomenal in what they do. Despite being commercial galleries successfully participating in international art trade, both have regarded the commercial aspect as a means rather than a goal unto itself. In other words, they have been using the free-market mechanisms to present an ambitious artistic offering. Put simply, Raster and FGF took upon themselves some of the public institutions’ duties (Raster at home, FGF internationally). From the most basic ones, such as the promotion of contemporary art among the broad public, something that did not exist for several decades, to more serious ones, such as the conscious and consistent building of Polish art’s international position.

The crowning achievement of this new type of institutional activity is the Avant-Garde Institute, a wholly new institution opened in Warsaw in October 2007 on the initiative of Foksal Gallery Foundation and Paulina Krasińska, the daughter of Edward Krasiński. It consists of the artist’s studio preserved in 1:1 scale and an empty, glassed-in pavilion (by the Dutch design studio BAR and Polish architect Marcin Kwietowicz) built on the terrace of the top-floor apartment. And though the Avant-Garde Institute is an institution in reverse, and its name is a jocular oxymoron, the idea behind it is very much serious: to create a wholly new platform for a theoretical reflection on contemporary art, and also on the still insufficiently researched Polish avant-garde tradition.

Functioning for over a decade now, Raster and FGF have established themselves firmly in the art world’s system, both in Poland and internationally. But the young galleries that have followed in their wake, encouraged by the pioneers’ success, have been unable to move beyond the rigid model of places that simply sell art. Their programs aren’t bad, rather bland. Quite simply, they lack intellectual zing and the desire to make a few risky gestures. 2008 and the beginning of 2009 brought us admittedly a few interesting debuts — Stereo Gallery in Poznań or A Gallery in Warsaw (a young artist, Tymek Borowski, who is represented by it, just took part in Prague Biennale 4) — but we are still talking about a gallery market that is only budding. Suffice to say that Berlin, for instance, has some 400 contemporary art galleries, while Warsaw has perhaps 20. In the other Polish cities, it is far less still. Yet the collecting boom has arrived in Poland and young successful Poles have realized that art is something you can invest in and make money on. New galleries are certain to be springing up, the only question is whether they’ll be just “art shops” or rather places attempting to capture the spirit and melody of their generation. A melody not necessarily nice-sounding for the mass audience. But now, when artists, collectors, critics, audiences and first of all potential exhibitors are well acquainted with the rules of the international art world, is it possible to repeat Raster’s and FGF’s model?

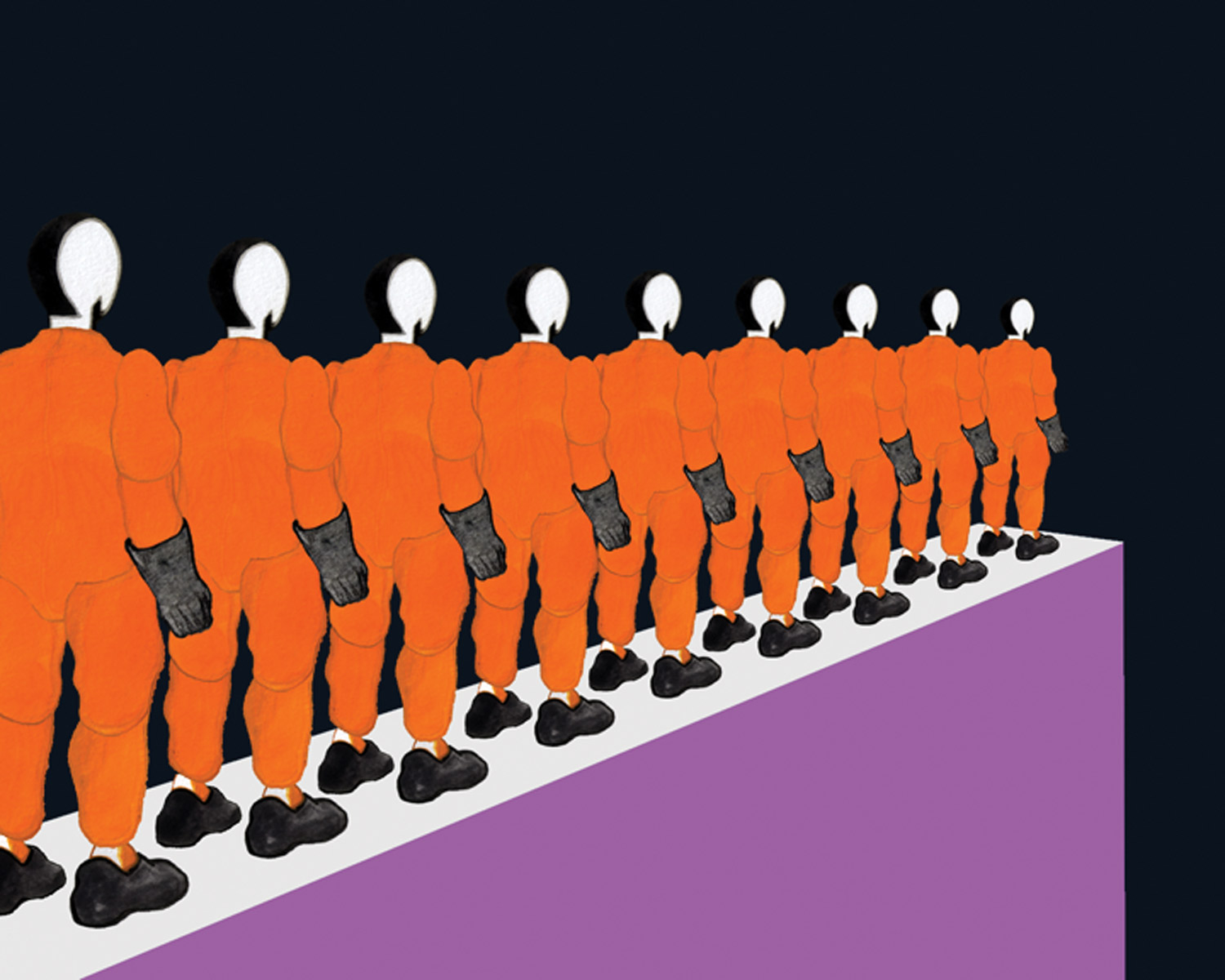

It is not only gallery owners that have left a gap yet to be filled. It is also the generation of artists who, as Monika Sosnowska put it, “learned everything in one system and entered their adult life in another,” representing a level that few other artists have been able to match. One of the factors responsible for the blandness of new artistic propositions is their surfeit. While the languages and poetics characteristic for contemporary art have become not only popular in Poland but actually trendy, young artists don’t really know how to use them. What they lack above all is originality, and this means that Polish galleries are dominated by mercantile, one-dimensional “art-fair art.” It needs to be added that the model of committed art, developed in the ’90s and derived directly from late post-modernist thought, has now become obsolete.

For as Slavoj Žižek writes: “Late capitalism contains in an unprecedented fashion its own ‘excess,’ and therefore every attempt to break out and transgress its domain becomes an internal transgression foreseen by the system.” Those Polish artists who want art to be involved in current politics should therefore propose a wholly new strategy.

And it is perhaps precisely because of being tired with art resembling in this or another way the daily life-immersed practice of Wilhelm Sasnal’s generation (artists born in the ’70s) that the most interesting artists of today are exploring imaginary realms, alluding to the Surrealist tradition, almost completely forgotten in the last twenty years. For now, this has been happening chiefly in the field of painting (the above mentioned Kowalski, also Jakub Julian Ziółkowski, Przemysław Matecki or Paweł Śliwiński, but also among underrecognized artists of the former generation, like Piotr Janas), but it already appears a proposition with strong potential and, above all, a fresh one. Still, it’s hard to say whether this and similar poetics will eventually form a current in its own right. Penerstwo Group from Poznań, an example of a wider phenomenon called New Poznań Expression (represented by, for example, Wojciech Bąkowski or Piotr Bosacki) is also worth mentioning.

One thing is certain — the bundled energy has become dispersed and will never return to its previous state. We shouldn’t expect another eruption of Polish art to be seen by the international art world, but rather a monotony of artistic overproduction interspersed from time to time, perhaps, with some outstanding talent. We are in an in-between period when the new has not fully emerged yet and the old still remains alive. And we are only realizing that we have again found ourselves in a completely new situation and have to learn the rules of the game again. A game in which contemporary art and its strategies are more popular than ever before. This time it’s surfeit rather than shortage we have to cope with.