December, 2004. While the Orange Revolution unfurled over Ukraine, about twenty artists slipped into the crowd of protestors, militant campers and police, and rejoiced in this unique opportunity to exploit a new political field of action. The R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space) group had just been born and, with it, a whole new art scene in Ukraine. Taking up the torch from their elders, marginalized since the Soviet Empire for having created in Ukraine a zone haunted by utopia and the absurd, this new generation does not abide by the rules, inhabiting, as they do, public space in carnivalesque performances and deploying parodies of political slogans. Yet again, Kyiv’s site of artistic resistance CCA (Center for Contemporary Art at NaUKMA) was transformed into an experimental laboratory for this collective who over the course of a year mounted exhibitions, actions, meetings and workshops. Fifteen years after the fall of the Soviet empire, the city again became a platform for creation for these 20-year-old artists for whom the West is no longer a myth and the East is no longer a dominant power. But what could the preoccupations of this new post-Soviet, post-Chernobyl, and post-Orange-Revolution generation be? Between desires for change and egocentric affirmations, the contemporary Ukrainian scene is trying to insert itself onto the international stage.

Unpredictable, audacious and captivated by questions linked to language, the R.E.P. group, today reduced to six members, has been continuing its investigations since the events of 2004. Imposing itself in only two years upon the international art scene, since 2006 the R.E.P. group was present, among others, at the Tallinn and Prague biennales, the Pinchuk Art Centre and the exhibition “Progressive Nostalgia,” curated by Victor Misiano, in Prato. Their most recent project, Patriotism (2007-2009), consists of an alphabet of signs whose objective is to become a common, universal language. Playing on collective memory, this in situ project, which changes according to its exhibition context, is liberally inspired by Soviet propaganda techniques. Mixing irony, humor and subversion, the combination of several logotypes allows the artists to develop different clichés about Ukraine and Europe, in addition to questions regarding immigration and corruption. Each member of R.E.P. group maintains a personal practice that enriches the collective work of the group through the affirmation of the individual. Thus, Mykyta Kadan (born in 1982 in Kyiv) maintains a pictorial practice of chaos, modern melancholy, nourished by an iconography drawn from the media. Janna Kadyrova (born in 1981 in Brovary) produces all kinds of everyday objects in ceramic, which she then installs, creating at times a sense of ambiguity regarding status and scale of given objects. Staged or installed in situ, Janna’s work seeks to invest a bit of color into a world that is sometimes too gray. Volodymyr Kuznetsov (born in 1976 in Lutsk) collaborated with Ingela Johansson and Inga Zimpich on the project Post Funding East Europe (2007), a documentary and an exhibition retracing the recent history of institutions in Ukraine. Aware of the currently still very precarious context, the three artists want to build an archive dealing with institutions dedicated to protagonists of cultural life in Ukraine. Lada Nakonechna (born in 1981 in Dnipropetrovsk), Kseniya Gnylytska (born in 1984 in Kyiv) and Lesya Khomeno (born in 1980 in Kyiv) are also members of the R.E.P. group, still working individually with painting and installation.

Founded in Kharkiv in 2005, SOSka is both a non-commercial gallery and the name of an artist collective. Created by Mykola Ridny (born in 1985 in Kharkiv) and Anna Kriventsova (born in 1985 in Evpatoria), their project was inspired by the figure of local artist Boris Mikhailov, known for his photographic work about human and social misery after the fall of the USSR. With the film Be Happy (2006), shot with Bella Logachova (born in 1976 in Mariupol), the artists emancipated themselves from this dark and tormented heritage through the portrait of a young homeless woman living at the margins of society, and nevertheless remaining optimistic in the face of any hardship. More influenced by the economic and social situation in Ukraine and the art market in general, the project Barter (2007) shows the artists in the Ukrainian countryside, bartering reproductions of paintings and photos of famous artists for local products. Barter refers to a parallel economic system of trade, which was widespread after the fall of the USSR, when money was completely devalued. The project Dreamers (2008), shown at Pinchuk Art Centre, also reflects feelings of fragility and insecurity through focusing on subcultures of the Ukrainian youth scene.

Opposite to this multiplication of initiatives are a number of individuals whose work — widely varied — addresses more personal issues in order to finally take up more universal questions. As such, Masha Shubina (born in 1979 in Kyiv) likes to take photographic portraits of herself, alone or with friends, dressed and undressed, provocative or more reserved. The artist uses this source of imagery to paint self-portraits that she puts online on different social websites and web mailboxes. Far from wanting to initiate some kind of intimate relationship, the artist seeks rather to meet new curators and gallerists. In her project Digital Narcissism (2007) Shubina intelligently mixed traditional practices and new media, transforming social websites into exhibition spaces. The more recent “My Own Religion” (2008), “My Dear Curator” (2006) and “My Music” (2008) explore invariably what the artist listens, reads and sees… Creating a lively and visual diary of her own life as a modern Ukrainian girl, Shubina plays with all the clichés related to young women from the East, between glamour, Western cultures’ fascination and banality.

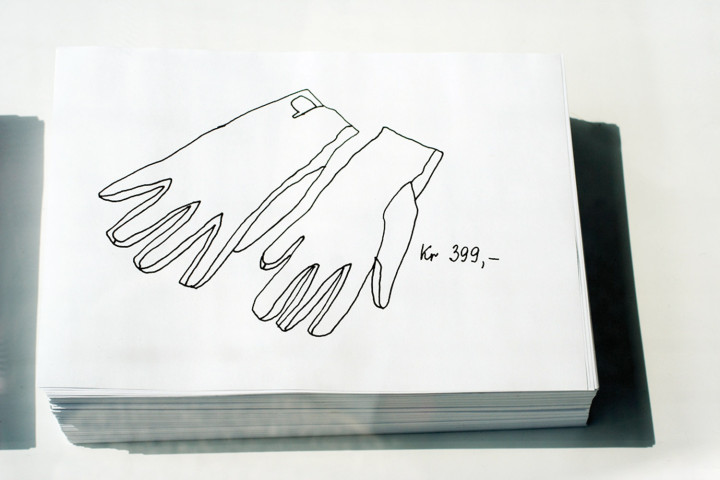

Pursuing a more conceptual practice, Alevtina Kakhidze (born in 1973 in Zhdanovka) has made of her life and her desires the very subject matter of her art. In 2005, upon graduating from the Jan Van Eyck Academy, Alevtina decided to publish a book on Zhdanovka, a small city in eastern Ukraine, upon which nothing had ever been written. When researching the project through collecting diverse facts, inhabitants’ memories, and information on the net, the artist realized that several cities of the ex–Soviet Union have the same name as her city. Thus, through the singular narrative of her city, Alevtina Kakhidize tells the story, between fiction and reality, of all the cities, which share among them poverty, isolation and human failure. Over the course of the past few years, during her stay in Western countries, Alevtina Kakhidize has taken on the habit of drawing consumer goods (hand bags, watches, gloves) that she contemplates in shops windows, adding the price of the object to the drawing each time. More recently, this practice was extended to works of art, the results of which have been assembled together under the title “Private Collection, 2007-2009.” Aware of the impossibility of possessing all of these desired objects, yet living in an ultra-consumer society, Alevtina appropriates these objects, or rather what they represent, through the simple fact of drawing them. Like R.E.P. group, Alevtina Kakhidze is also active as a curator and art critic. Winner of the Malevich Prize in 2009, she is one of the founders of the web journal KrAM.

Ivan Bazak (born in 1980 in Kolomya) has made of his condition as a Ukrainian artist living in Germany the central point of his work, letting it be profoundly influenced and nourished by his experience. What happens when you move away from your country, your city? What do you bring with you? What do you leave? In his exhibition project “Where is my home? Where are you at home?” (2008), the artist retraces the itinerary of his friend Vitalik and a whole community of immigrants living between Ukraine and Italy. Paintings, videos, photos and small models of abandoned houses document the traversal of these uprooted individuals.

Living in France for several years and fascinated, for other reasons, by cabins, makeshift housing and other provisional constructions, Kristina Solomoukha (born in 1971 in Kyiv) makes watercolors, embroideries, sculptures and videos that are equally interested in the idea of movement, flux and memory, and in intersections that never lead to any kind of meeting.

For Mark Titichner’s work, featured at the 2007 Venice Biennale Ukrainian Pavilion, the R.E.P. group came up with the slogan, “We are Ukrainians, What else Matters!” This slogan, despite an uncertain institutional situation, a non-existent market, a chaotic political and linguistically divided climate — reinforced however by the opening in 2006 of the Pinchuk Art Centre and the recent creation of the Pinchuk Art Prize dedicated to young Ukrainian artists — illustrates the way in which Ukrainian artists are no less convinced of their “omnipotence.” As R.E.P. affirmed: “We are Ukrainians, We need nothing!”