“We are tragic sleepers,” texts Miciah sometime in October.

He and I happen to be birthday twins, as were our mothers. But more than that, we are insomniac doppelgangers.

Some time ago he curated a show at Bridget Donahue gallery titled “On Empathy.” The New Yorker’s review of the exhibition said that in a time when we seem to lament irony and detachment, Miciah “makes sincerity cool again.”

Although this was a few years back, sincerity has been on my mind a lot lately. I have especially been thinking about the kinship between insomnia and sincerity.

Daniel, a curator friend I much respect, was at a dinner at our house last November. He said, “The most radical thing today is to be friendly. Everything else has turned into self-branding and is used for collecting data. Friendliness is the perfect way to disappear, to be invisible.” I think by friendly he meant empathetic, and, at the risk of sounding trite, I also want it to mean “nice.”

Today, I went to get my thyroid checked in an enormous hospital across town. On my way out of the infinite maze, rushing home to finish this text on time, I noticed a very anxious old man looking lost in the disinfected hallways. There was a bureaucratic mishap with his appointment, and German receptionists kept directing him in a loop. Meanwhile no one could find him in the system. I ended up spending two more hours in the hospital than I had planned to, getting to the bottom of this lightly Kafkaesque riddle. For a working mom, time has the worth of gold, so I kept chastising myself for being too empathetic and not professional enough to make a deadline, even though it was obviously the only way to go.

In an interview, filmed in São Paolo in 1977, the year of her death, Clarice Lispector was asked when it was that she decided to become a professional writer. “I never did,” she responded. “I am not a professional. I only write when I want to. I’m an amateur and I insist on staying that way.”

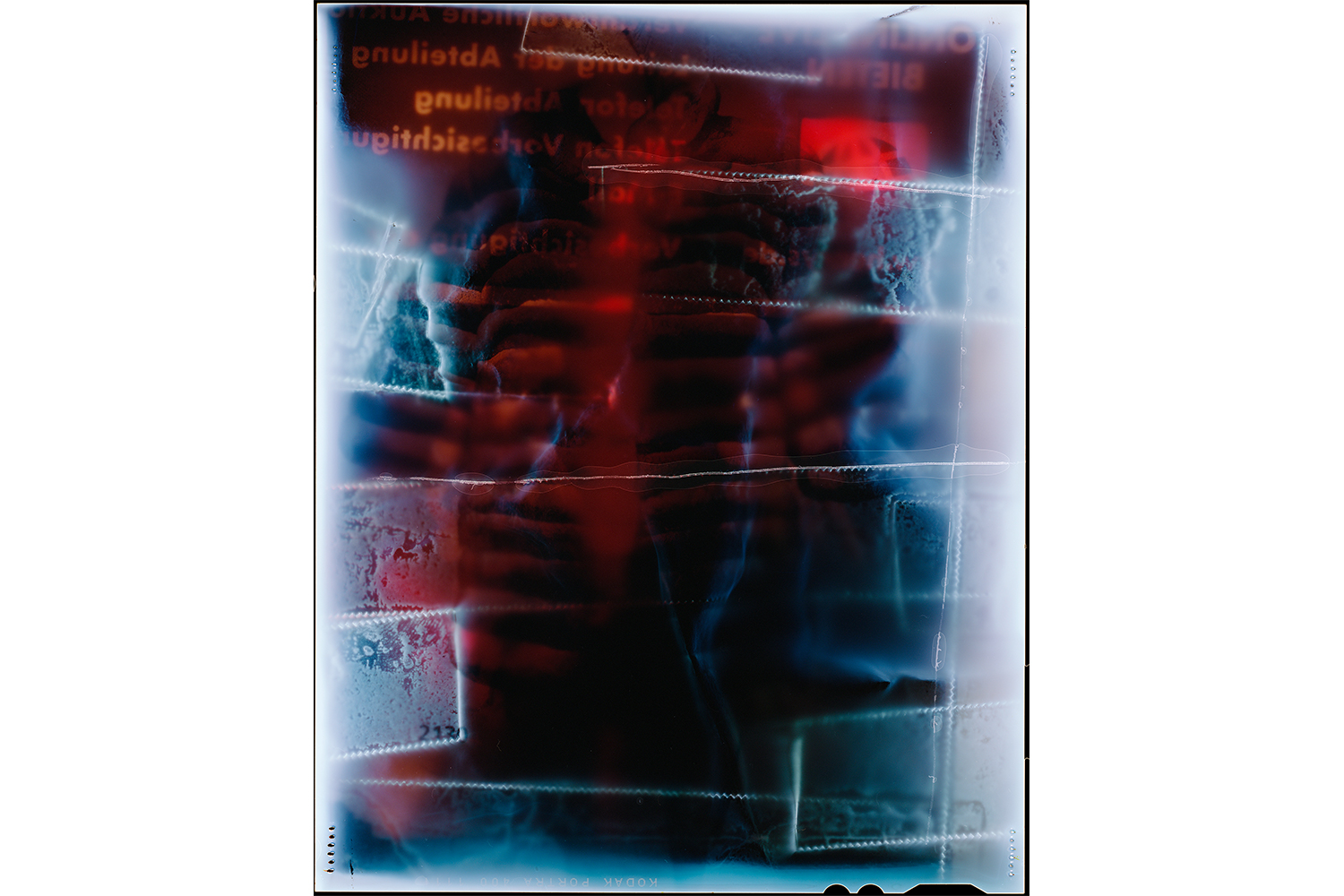

As I sit on the hour-long bus ride back home, scrolling on my phone, images of kids bleaching their brows and wearing fashions from the 1990s overwhelm me. It’s not a homesickness, although I am homesick for the seeming radicalness of my teenage years. Rather, it’s a melancholia induced by the meta-ness of everything. I was texting my friend Leila the other day, saying that the clothes we wore back then felt radical. The weirdness of it was sincere. I was living in London, modeling for The Face and i-D magazine, not getting paid anything, bartending. I didn’t think of it as a career. It felt like a good way to live, a way to meet fellow misfits and be part of something different until my body changed and my weight became a topic. At that point, sensing the seduction of an eating disorder, I turned away, ignoring casting directors’ calls during my time at Bard College, where I decided to go to study photography. The teacher we admired most at Bard was Adolfas Mekas, who only taught one course. Aptly titled “CINEMAGIC,” it was legendary. Each session featured an autobiographical lecture, followed by a screening of a film that was meaningful to him. You can find some of these on YouTube.

Last spring, on my first trip back to NYC after the pandemic, I found myself walking by a Vatican-scale gallery that I’d neutrally passed by many times in the past. This time around, however, the sheer size of it filled me with a malaise of intentions gone awry; I realized that I never intended to be part of a world this corporate.

“I chose to become an artist because I wanted to be a failure,” started a Mike Kelley quote I came across online in December. “When I was young, if you wanted to really ostracize yourself from society, you became an artist.” Thinking of saving this interview to share with my future students, I realized that, at what seemed like the top of his career, feeling the pressure to play the big art game anyway, Kelley killed himself. There must be another way, I thought — another way to live with this clump in your throat.

Although we can never claim to be as radical, us 1990s kids also craved something outside of the normal idea of success. We wanted to make art because it was the only way to live with the knot of weirdness that seemed to be permanently stuck in our throats. A weirdness that one never thought oneself capable of branding, because it was not communicable in a regular manner. Now a lot of us are wearing the same clothes, but with the purpose of signaling that we possess sophisticated information about that time. I suspect that that information, despite being promoted as powerful, might not be knowledge.

Today is a day when I don’t know anything, probably due to the extremely short hours that I have been sleeping lately. Do you know the color of your hair, you might be wondering, or the name of your child? I do, I do. I also comprehend what is going on in Iran and Ukraine and the impact of that on our future.

But it is not this kind of knowledge that I mean.

I read that sleep deprivation is associated with homeostasis, hallucination, delusion, illusion, distortion, metamorphopsia, and misperception. This might be true in extreme cases, but in my manageable case I beg to disagree. When I don’t sleep it feels like I step entirely outside the reality of life where rules of the game fall away. Observing my surroundings, I feel like a lay person looking at newly released images from the Webb Space Telescope, the largest, highest-resolution infrared camera in existence. I know the world contains vital information about the universe, but I also know that I am incapable of fully reading it. It’s confusing, but it feels like witnessing infinity. In this state, I’m a glowing dust particle among trillions of others, and the only forward-moving energy is that of love.

In January I attempt to relay this sensation to my husband, Andro, and he reminds me that when we first met, eighteen years ago, images of space would fill me with mortal dread. I guess I have come a long way.

Mulling this over, I dug up a quote that has stayed with me since college, from Franz Kafka’s letter to his friend Oskar Pollak, written in 1903: “We are as forlorn as children lost in the woods… For that reason alone, we human beings ought to stand before one another as reverently, as reflectively, as lovingly, as we would before the entrance to hell.”

Kindness is still the most radical thing.

Berlin – Tbilisi, February 2023