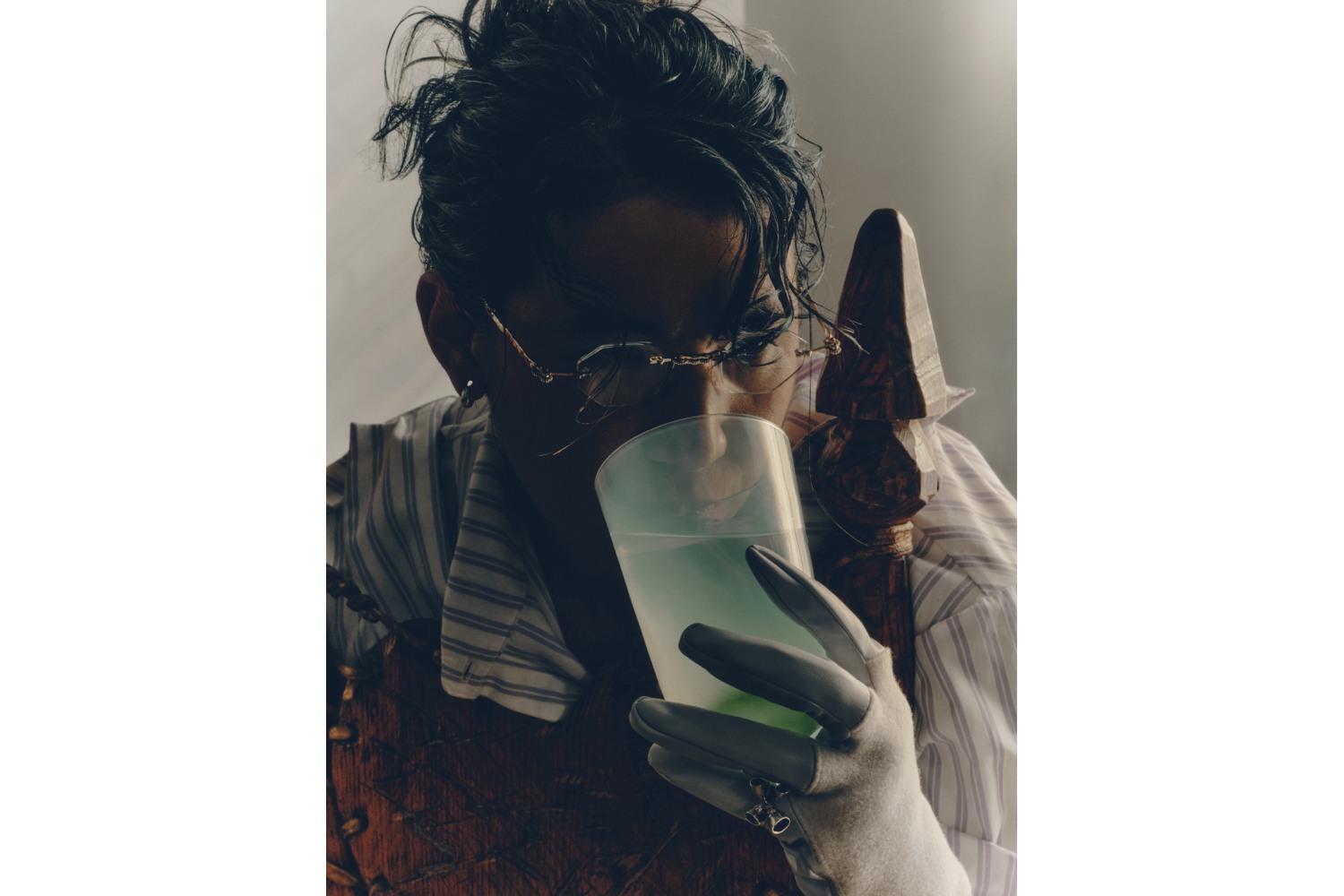

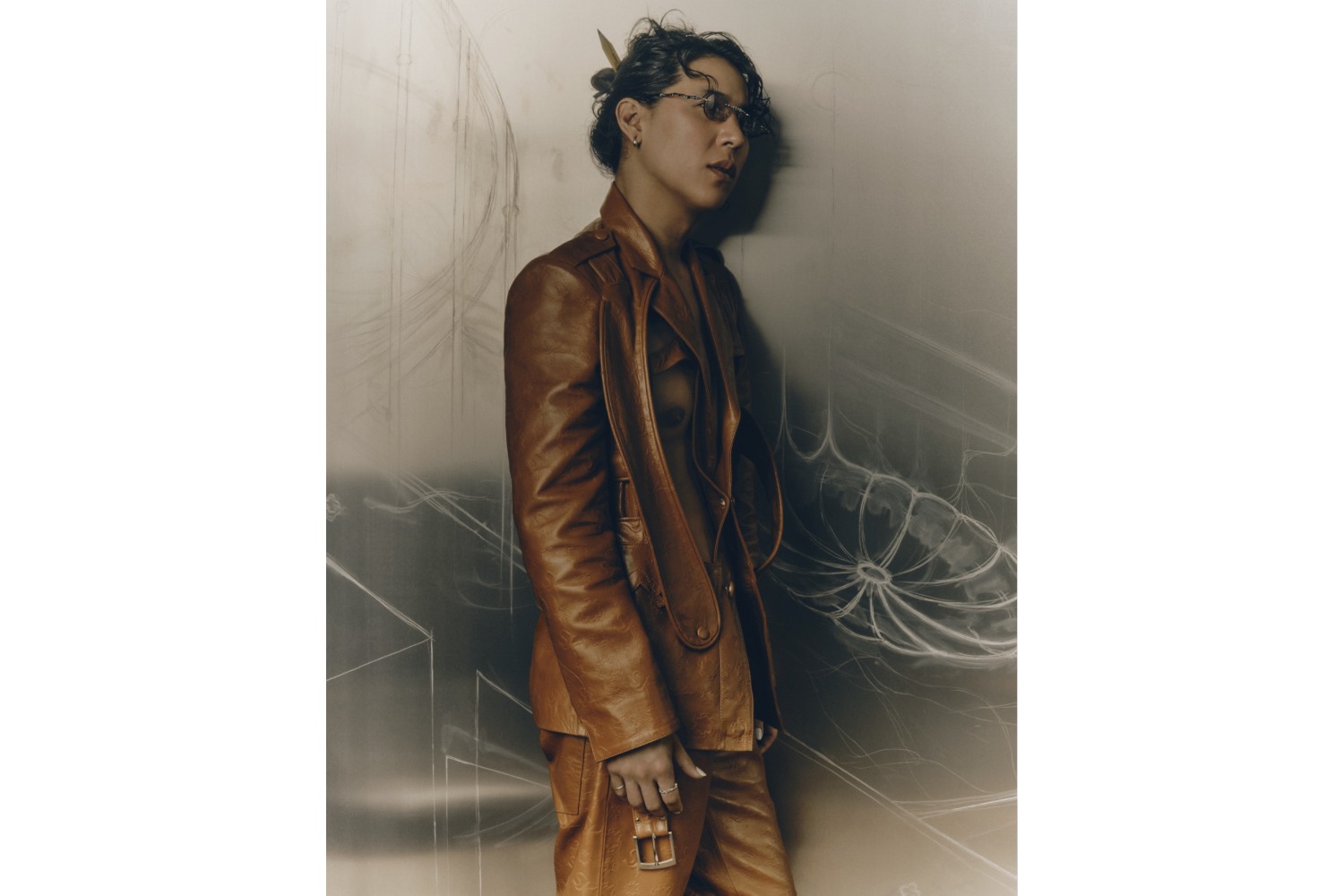

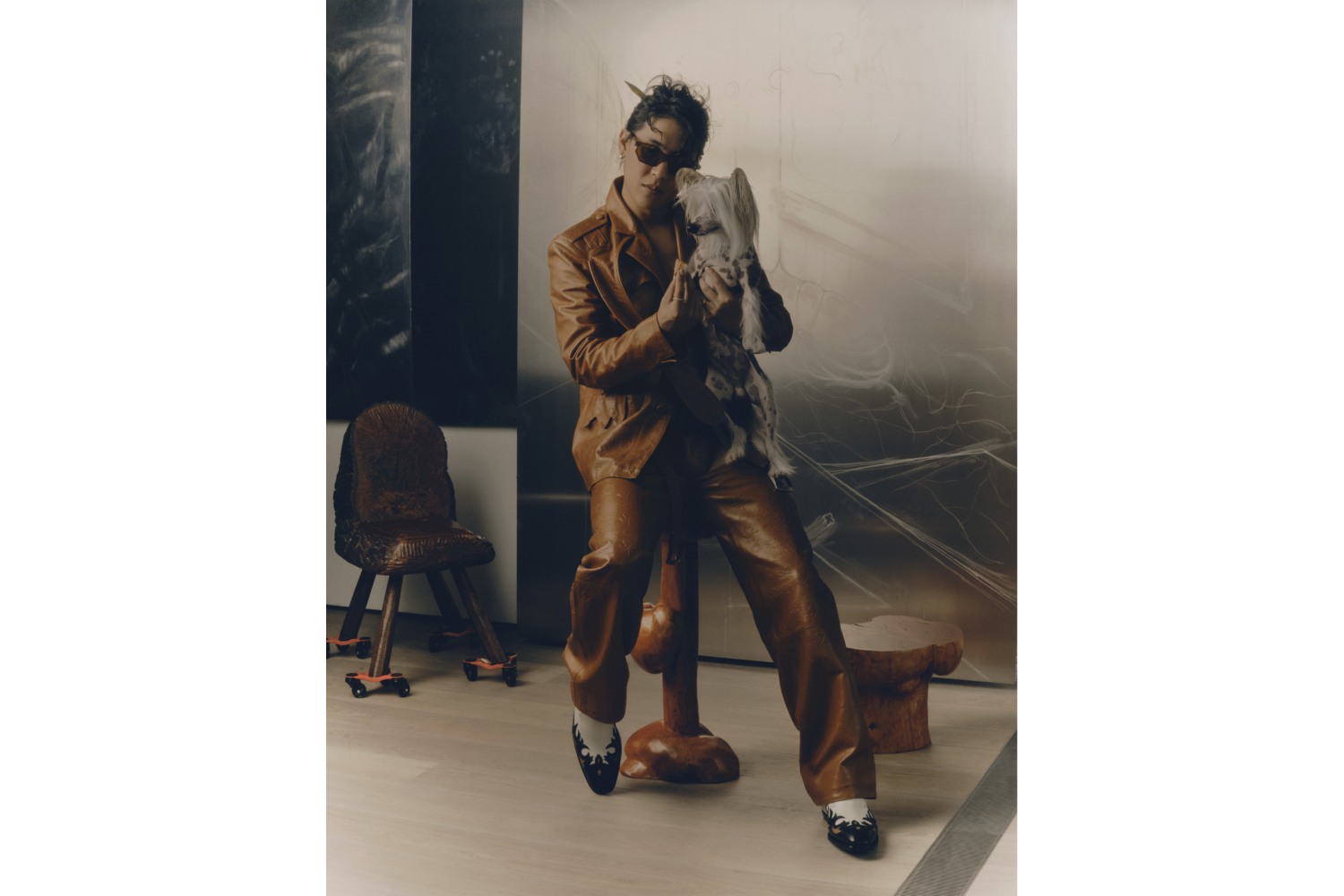

What does it mean to live comfortably between worlds? Adaptation does not always guarantee success. Think of recalibrating any timeworn behavior to a new set of norms: How often does the act guarantee recognition and acceptance? To WangShui, living well means appearing as they wish — and disappearing at will. To guarantee safe passage through milieus, countries, and public perception, they have tried on disguises; encrypted images, language, and expression; and dispersed into smoke to protect their core. The artist has lived as a drone, a dragon, a mollusk, a silkworm, an evacuated snakeskin. A smear of oil on an aluminum panel, a bit of acid, a twist of LED light. They have evacuated the public arena altogether, scrubbing the record of any visual representations of themselves, and returned to dazzling corporeal form in an interspecies photoshoot for Interview Magazine. In the pictures, they are plunged into a substance that could be plastic or water, hugging their Chinese crested dog named Psychic. Their voice has issued forth, live and disembodied, from wall-mounted speakers and Le Corbusier chairs. They have shrunk themselves to a single strand of data, and grown to the size of a dynasty, splitting and reassembling their personae and lives until what is perceptible is an annihilating shimmer.

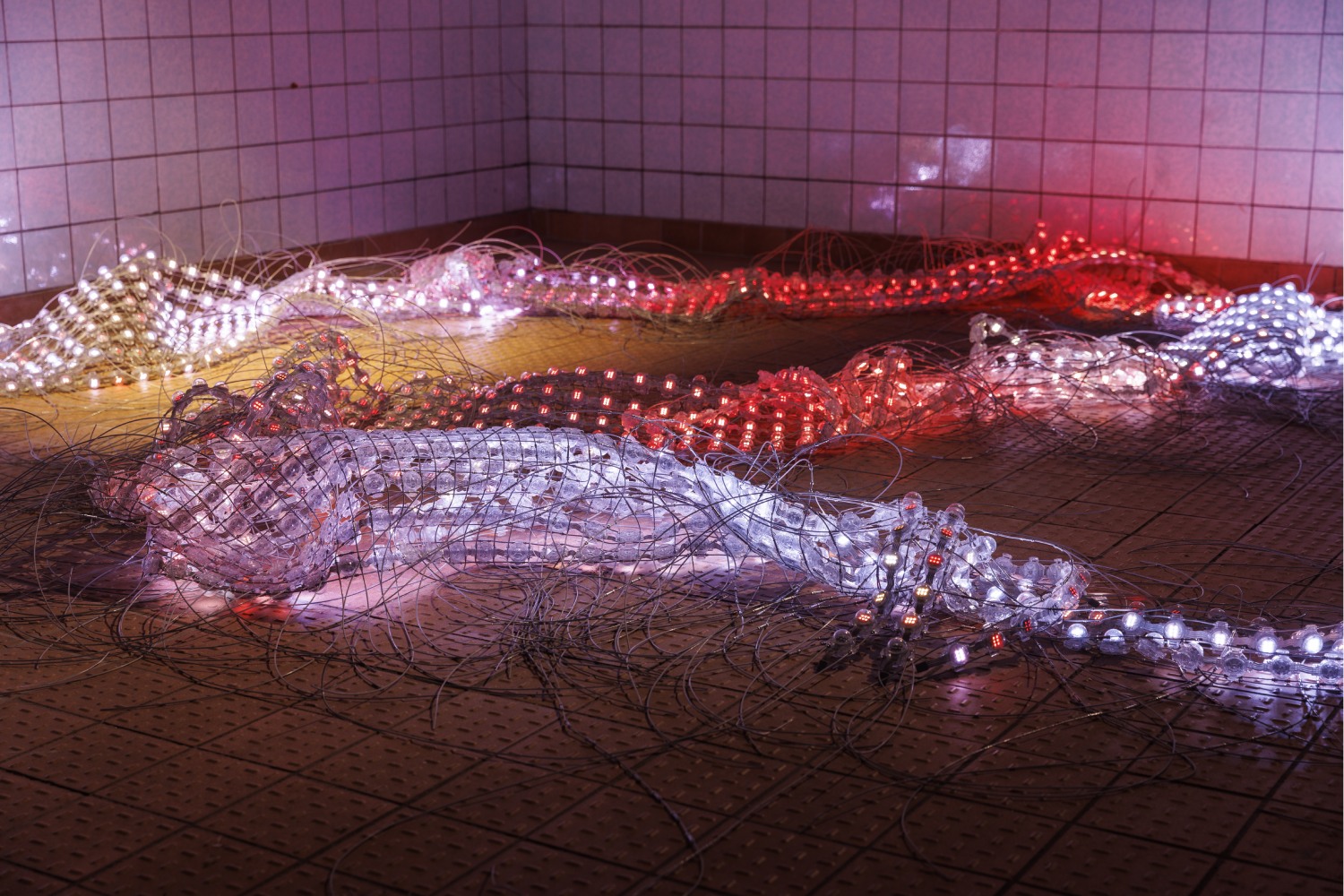

Exile is where we begin. I had returned in time to call WangShui on my geriatric iPad, rushing breathless down a hotel hallway to find them on the other side of the portal, sitting in a crisp beam of upstate light. I sit on the floor and listen intently as they describe their recent trip to the Gobi Desert. They had arrived in Shanghai to complete “poiesis” (2023) for the Rockbund Art Museum. Over the course of the exhibition, a suite of aluminum works would migrate around the gallery, responding to ultrasonic material captured and interpreted by a custom algorithm in real time. Atmospheric information would reorder the artwork around human presence in the gallery. Upon arrival, WangShui found themselves more embedded in the Rockbund than they’d intended. A paperwork mishap at the border meant they couldn’t access their ID or cash flow. Their handlers at the museum became intermediaries for even the smallest transactions, from buying a toothbrush to ordering food. The trip to the desert was one of their only excursions out of the complex, and it flipped them back three thousand years when they entered the Mogao Caves at a historical junction in the Silk Road. Following the beam of their flashlight, they encountered Buddhist art spanning a thousand years, preserved in the lightless, dustless environment of the chambers. The cave paintings served as meditation aids, teaching tools, and narrative logs. The accumulation of earthly and spiritual knowledge, represented pictorially and in layers, resonated with their ongoing interests in ancient spirituality and artificial intelligence. Other intelligences can be oracles. Like the Mogao paintings, they can be hyperdense artefacts of civilization that collapse linear time. Think of how AI models parse repositories of knowledge to speak or dream it back in response to human prompting. For WangShui, the models’ imperfect or hallucinatory outputs — a hindrance to the utilitarians among us — become an opportunity to reroute habitual thinking or form a window onto previously unseen psychic patterns. Their work is often reassembled in step with sensing algorithms, such as the one informing “poiesis.” In Scr∴pe (2021), a generative adversarial network (GAN) digests images of deep-sea bodies, fungal structures, cancerous cells, and baroque architecture, broadcasting mutating forms from behind a ring of luminous wire resembling the hot edge of a fresh bullet hole. The latter also contains sensors that respond to changing carbon dioxide and light levels in the gallery space. There is a sense of repeated encryption and decryption, obfuscation and revelation. Of a fixed logic at work, which is nonetheless open to disturbance from the life-world — where it is the error that gives the logic reason to exist. WangShui’s empathy for alien sensibilities is another refraction of their personal experience, another set of mirrors purpose-built for disorienting representation for an artist who does not balk at self-exploration but resists having their inner complexity simplified or overexposed by the media circus. Gardens of Perfect Exposure (2017–18), shown at the Julia Stoschek Collection, held dozens of pupating silkworms in a habitat of ring lights, chrome fixtures, mirrors, glass, and human hair. Though a set of camcorders broadcast a live feed from every angle, and the ring lights flooded their world with light, the worms were still protected from capture by the material of their transformation. What transpired within each cocoon remained a mystery. “I’m interested in… entities that have the power to appear and disappear and thus can never be fully captured,” WangShui says in a video for the Rockbund 1.

Perfect exposure: to light, or to danger. Gardens references the Gardens of Perfect Brightness, famously looted into oblivion by British troops during the Opium War, which have “become a symbol of China’s subjugation at the hands of foreign powers in the nineteenth century, and hence a focal point of modern Chinese nationalism,” writes Lillian M. Li. “Ironically its very power as a symbol rests in its physical invisibility… Although there is ‘no there there,’ the Yuanmingyuan is everywhere in the Chinese national consciousness.”2

The artist, raised by Chinese Christian missionaries in Chiang Mai, points to sermons as a first interest in elaborate staging — how spectacle shrouds the “no there there,” intensifying a sense of connection while protecting the mystery within. “I look at landscape paintings more than any other kind of art,” says WangShui in a 2022 interview 3.

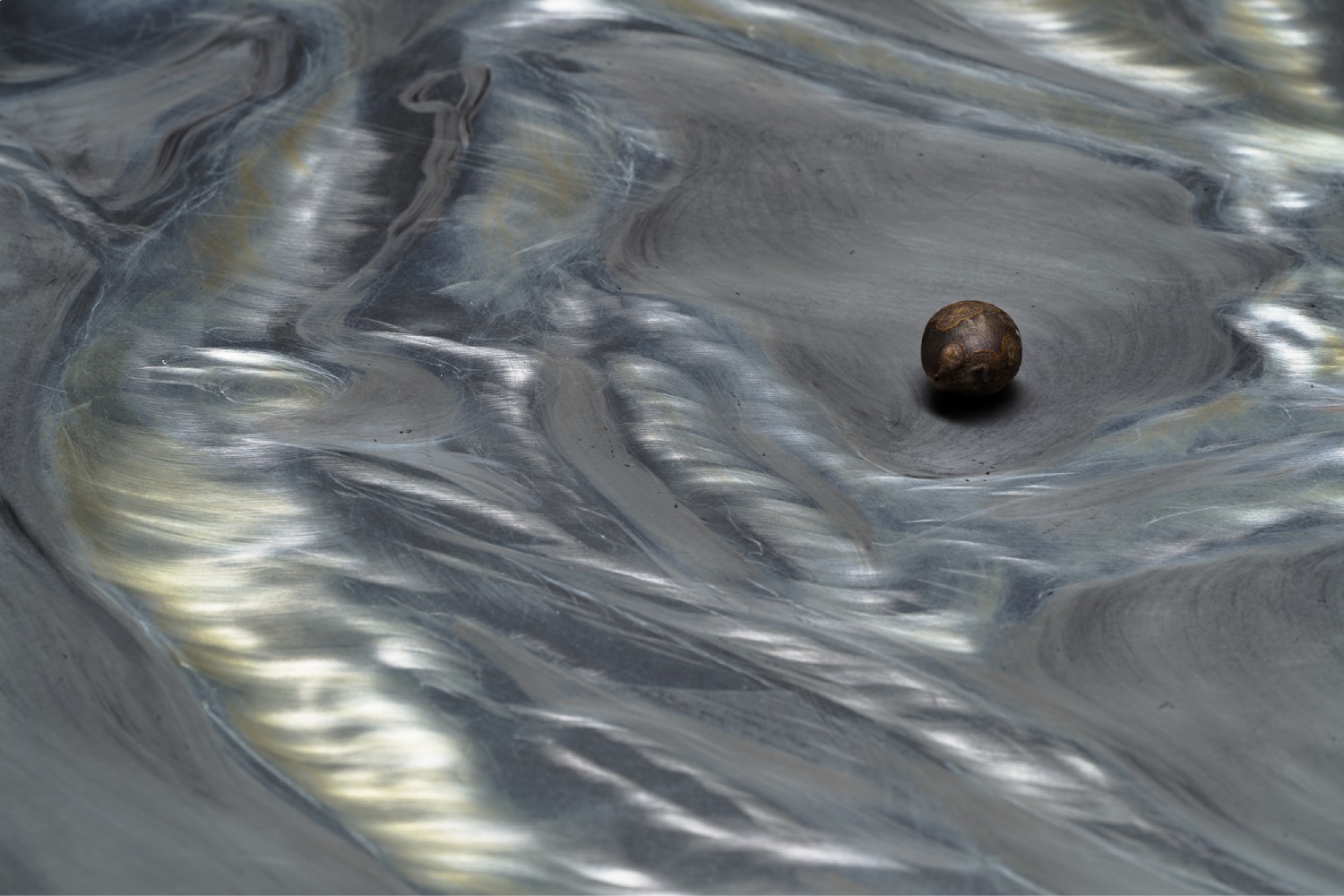

Given their panoply of concepts and materials, the influence may not be immediately discernible to a human viewer, yet the GAN trained on a set of the artist’s own paintings picked up on this formal underlayer, returning a series of landscape-like patterns that WangShui then translated back onto aluminum panels for both the “poiesis” exhibition and the Isle of Vitr∴ous suite (2022). The process of etching the panels is “like nails on a chalkboard,” they say to me, “but I enjoy it.” I watch a video where they’re depicted in progress, moving a scouring pad in small, deliberate strokes across a massive shining panel, buffing the corruption in. At the Lyon Biennale, the largest section of the Isle, a panoramic landscape titled Hyphal Stream (2022), is mounted on a mesh-covered scaffolding that contains a vat of aerogel, a lonely organ whose hydraulic pump circulates the “lightest solid on Earth” across the painting’s nacreous ground, where it makes a brief impression before diffusing into thin air 4.

During our conversation, the artist described these paintings as a liminal landscape “found” between AI and the self — a revelation born of the interface between two aliens, where new forms arise from an attractive incompatibility, and synthesis occurs as a translation between two discrete yet communicative systems. What can we call the generative zone between form and intuition, being and nothingness, self and other? In the paper “On the Varieties of Experience of Art” (2023), the philosopher Yuk Hui has described the third space as the “gate to all subtleties.” Where landscape paintings of Western provenance evoke the sublime through figuration, Hui argues, shanshui paintings provide a portal into transcendence through what he calls “blandness” — the transit between form, sense, forgetting, and transcendence enabled, deceptively, by the paintings’ indistinct formal qualities. These are paintings that refuse exactitude, but don’t relinquish ties to the material world. “Recursively throwing [the subject] into broader realities [allows it] to recognize its own insignificance and appreciate its existence not as master of nature but as part of dao,” he writes 5.

WangShui’s oeuvre can be read through shanshui, though in place of ink and water they will deploy an oil, an aerogel, an architectural void, or an algorithmically interpolated material to surface the gates. Isle of Vitr∴ous is titled after the jellylike material that envelops the human eye: the biomaterial gate that mediates perception and image, encountering and sensing. Rupturing and refracting light, the panels are di “cult to photograph. Nearly all of WangShui’s oeuvre is, which isn’t to say the works aren’t photogenic. The resistance to being captured wholly — which may seem like a simple problem of documentation at first — underlays the entire endeavor. “The dragon I have in mind doesn’t have a singular body. It shifts between endless vantage points, aggregating an infinite live image of me. Its name is WangShui.” So goes the voiceover of an early work, From Its Mouth Came a River of High-End Residential Appliances (2017), which has taken the form of a video installation and a live performance. In the video, WangShui and a drone operator named Hercules guide our POV through the “dragon gates” or voids at the centers of residential buildings in Hong Kong. The architectural concession to the belief that dragons need clear flight paths from the mountains to the sea has displaced millions of dollars’ worth of luxury architecture. The artist saw them as the most seductive kind of negation: the type that holds space for uncapturable freedoms, such as the movement of the dragon-spirit. In the voiceover, WangShui inhabits the dragon’s body to discuss incidences of shapeshifting and transformation in their own body and in myths where “deities are transgendered corpses and have names like Cry Spiral, Fish Wife, and Terrace.” Deity-like classification makes sense in a simulation, where sets of rules or logics determine how semi-autonomous agents interact with each other. A ruling personality trait colliding with another — say, Goddess of Aggression meets Goddess of Compassion — sparks emergence. The simulation “Certainty of the Flesh” (2022–ongoing) is “artificial drama” that draws from the artist’s life, ancient mythology, and reality TV, the latter for its inventive use of character-on-character micro-drama to sustain action without a narrative script. In “Certainty of the Flesh”, each character is a composite of traits, bodies, and beings.

They are based on the artist’s friends, in homage to how every person is really a mecha comprised of their clique — bringing to mind the oft-quoted adage that you’re “an average of the five people you spend the most time with,” usually attributed to motivational speaker Jim Rohn. The piece also draws inspiration from a form of trauma therapy which conceptualizes the self’s conflicting drives as a chorus of competing voices. Dysregulation, WangShui explains, surfaces the “wrong” voices; regulation can make voices that affirm, that make sense, rise above the others. Beneath floating layers of fiction, material, and myth runs an ulterior consciousness constantly analyzing and reconfiguring itself — like a recursive algorithm, like a sapient mind. Like Isle of Vitr∴ ous, “Certainty of the Flesh” is trained on a suite of analog paintings — that is to say, works on aluminum that the artist created prior to algorithmic enmeshment. Collectively titled Mindful Witness, these take the “brutality of representation” as their subject, specifically in reality TV. Each hyper-condenses the themes from the artist’s complex installations.

On our call, WangShui walks me through each surface, where props and stage sets materialize and denature like proteins. Beneath smoldering layers that evoke spotlights and limousines, there is a thin residue of violence. “I was interested in defiguration,” they say. “In the world that holds the figure.” Touching on a scene from The Bachelor where rival girls rip cheap crowns from each other’s heads — which, in turn, inspired their painting Queen (2021) — they refer to sfregiare, the Renaissance term describing the act of disfiguring one’s enemy with a slash to their money-maker. Historically, the violence was devised to end a sex worker’s career if they were deemed too dangerous by the very nature of purveying intimacy. Activities conducted in secret still resulted in lethal exposure. Armed with an arsenal of “sincere decoys” and a dragon-shaped stretch limousine that extends from the deep past and all the way into the afterlife, WangShui gives us a ride far out of total capture, through the “gate to all subtleties.”