One day in 2009 Wang Xingwei (b. 1969, China; lives in Beijing) was leaving the pigment shop at the gate of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, a school that he did not attend. He stumbled on a flyer announcing one of the many training courses for aspiring entrants to China’s top art school, the annual flood of eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds who come to town each year shortly after the spring festival to take a shot at admission in an examination ritual that mirrors the civil-service tests of imperial times. The entrance test had always been straightforward, asking participants to make drawings of plaster casts, live models, and the like — the rudiments of the decontextualized, Euro-Soviet academicism that will characterize those few lucky matriculants’ time at the academy. But, in recent years, to prevent the endemic cheating that has always characterized this system, the parameters have changed, asking test-takers now to render abstract concepts rather than specific objects, albeit still in a realist style. Consequently, the cram schools had to take a new tack, instilling not just painterly acumen but emotional and perceptive acuity. The brochure he picked up was meant to show how they did so.

The earliest set questions that runs through Wang’s painterly output might be phrased as: What is to be done with the history of realist figuration once the belief systems that underpinned its training and practice no longer function? Can a realism whose roots, at least at the level of pedagogy, are both socialist and academic, come to undergird a critical, conceptual practice? And can artists schooled outside the hallowed centers of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, in a place like a small technical college in China’s far northeast, compete in and with the metropole?

For Wang, an initial set of answers marked his work in the early 1990s, based on then-new (in China) ideas of combining motifs from Western paintings and his own lived experience into ambiguous narrative compositions. A painting like Evidence (1995) puts the artist into the posture of the risen Christ in Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601–02), pointing out his wounds as if to a doubting apostle, while standing in front of a typically flimsy early 1990s Chinese particle-board wardrobe, under a string of decorative plastic cucumbers and chili peppers. Poor Old Hamilton (1996) shows the back of a purple-suited man and the shamed face of the artist’s neighbor’s child, standing in front of a further shattered version of Duchamp’s “Large Glass”; the two figures are watched over by two other dismayed figures: a mustachioed Mona Lisa hung high on the wall, and a crouched Richard Hamilton (the most enthusiastic Duchampian of all the Pop artists) wearing Chinese cloth slippers and sitting in the chair of a security guard. These knowing assemblages were notable for two main reasons: first, they called out the legions of other Chinese artists whose 1990s practices focused with less intensity and nuance on directly aping precedents from Western art history; and second, they demonstrated a soft-spoken confidence, even arrogance, in the face of this tradition honed from an absurdist sensibility of integrating it into a Chinese material and intellectual universe that was self-conscious of its relative deprivation. Many grew out of intense dialogues with the Dutch curator Hans van Dijk. (In van Dijk’s archive, one finds the 35mm photographs that served as the earliest basis for a number of these compositions.) This conversation is said to have brought Wang from the provincial fringes into the center of a Beijing conversation that was then looking for possibilities for realism beyond the rote symbolism of “Cynical Realism” and the self-righteous turn of lens toward the common folk of the “New Students Generation.” These were the two great trends of early 1990s Beijing painting, which also imbued Wang with a skepticism of the Western artists then in vogue among his peers.

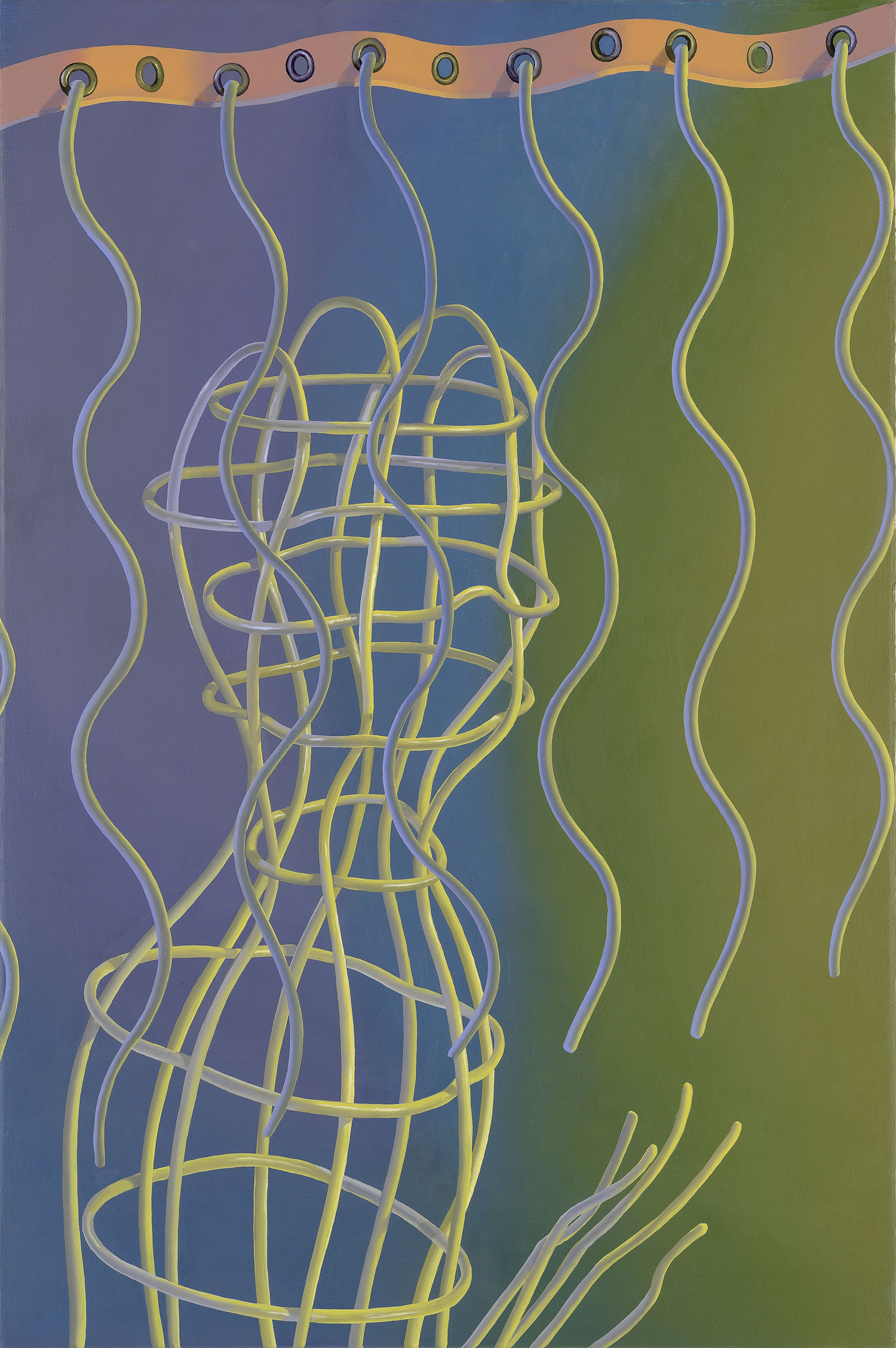

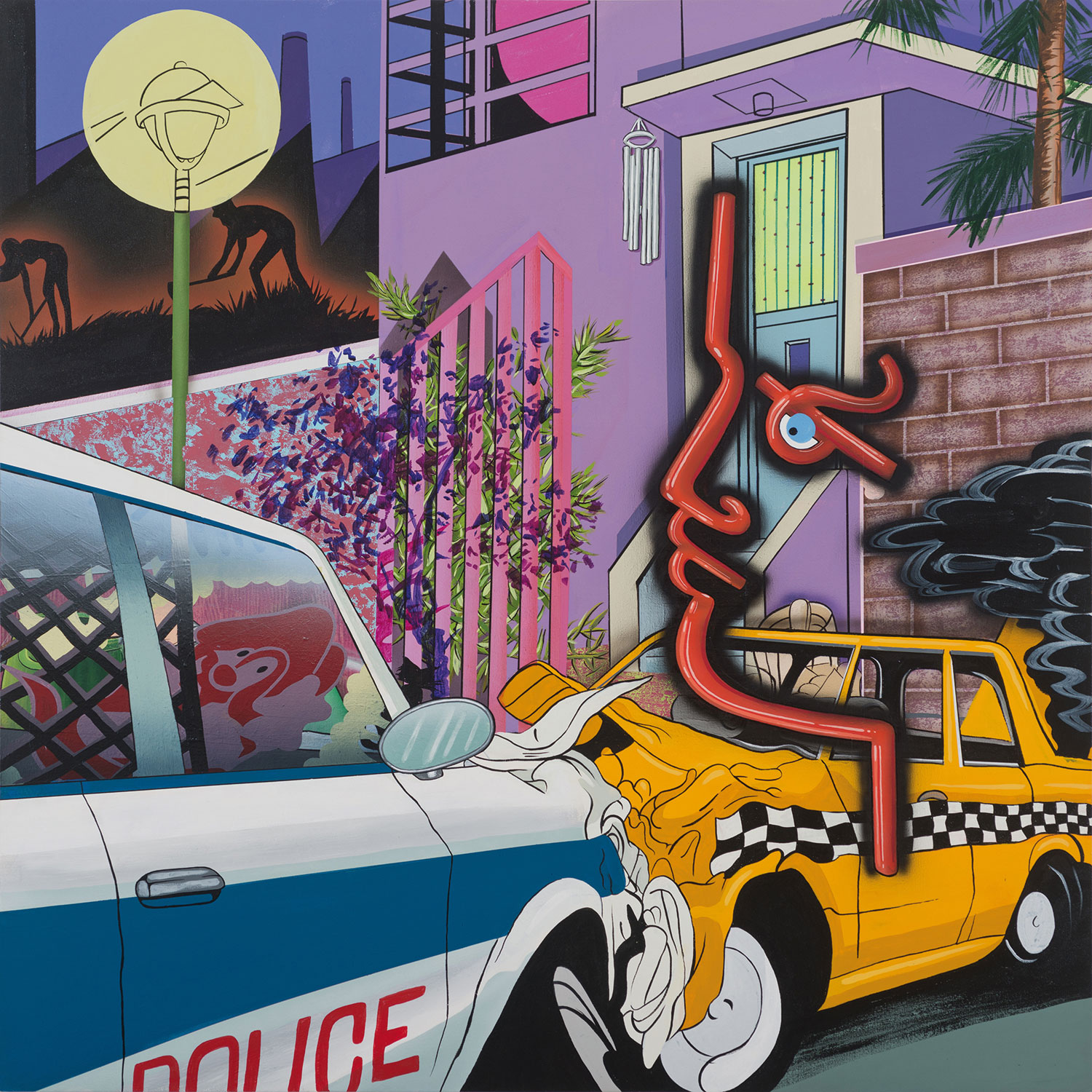

If he made his initial reputation with such direct citations of outside forms, Wang Xingwei’s evolution in the late 1990s and early 2000s led him toward a world in which it was possible to borrow and recombine images based mainly on motifs and stock figures of his own making. The purple-suited man, for example, recurred in the painting Untitled (Watering Flowers) (2013) where he uses his head (now transformed into a watering can) to hydrate a Picabian sitting nurse (herself one of a coterie of recurring, uniformed figures in another group of paintings) whose head has become a pot of flowers. References to other artists and histories are buried increasingly deeper beneath the surface, to the point where the artist resists exposing them to all but the most dogged of interviewers or closest friends. It is a strategy that leads us to look at his works less in terms of whom they cite, and more as an extended, Tarantinoesque family of characters, postures, objects and brushstrokes that are left free to reassemble in unscientific, even random configurations. Their intention is less to convey allegorical information than to give predictable visual delight.

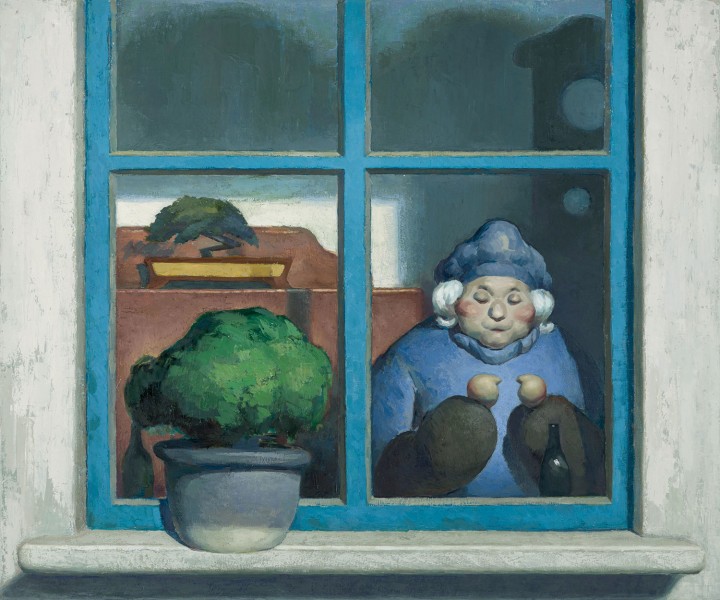

Back to the brochure, and the pigment shop outside the Central Academy: the “old lady” was first pictured on this giveaway handout, as an example of the sort of test-beating insight this training course would instill. There she appeared with her husband, threading a needle harmoniously with a clock behind her and a pot of flowers to her side. It was an anonymous allegory of the resigned intelligence of one’s waning years, responding to a prompt along the lines of “wisdom in old age.” Wang picked up the brochure, most likely amused by the rudimentary thinking and technique it represented — by the idea that an idea could be distilled so directly into so specific an image, and by the stilted if cursory attention this “answer” paid to key elements of painting such as composition, coloration, light, line and form. He brought the “old lady” back into the studio and let her live there for a while, thinking about what possibilities she might offer. From 2010 through 2012, she appeared in nine variations.

This subjective decision to dedicate the better part of two years of one’s output to a subject so arbitrarily arrived upon is almost Joycean in its boldness — some strange inverse of the “throwaway” newspaper Leopold Bloom tosses into the River Liffey. But aside from the quixotic or sardonic register on which this gesture of absolute commitment to an accidentally acquired flyer might be regarded, it resounds on a number of other levels: there is the notion common throughout art history of a theme and multiple variations. There is the gentle absurdity of the handling of the subject, as the woman appears constantly to be threading a needle that has been elided, to the ticking of a clock that has been stripped of its hands. There is the humor conveyed in what is in Chinese called “small intelligence” — the gentle toggling between textures and finishes, among varieties of flowers and distances of perspective. There are the references to other places in Wang’s oeuvre, whether through the window frame that mirrors the 1993 portrait of artist friend Wu Tao after his suicide in Untitled (Bonsai Old Lady) (2012) or the foliage, itself taken from the painting Big Tree by the Film Museum (2011), which seems to have landed on her head in Untitled (Flowerpot Old Lady) (2011).

But perhaps more striking than any of this is how the series works to affirm a commitment Wang seems to have made long ago: to the fundamental premise that realism continues to contain possibilities for advanced expression. In this commitment to teasing aesthetic heft and visual delight from inside the language of realism itself, he evokes no one so much as Jeff Koons. As the artist said in an interview at the beginning of the “Old Lady” series: “First making a value judgment and then giving it a form — this sequence is problematic. If you only talk about meaning, you remain unaware of the orientation that underlies its foundation. I’ve always been very interested in commercial painting because in a different sense it strictly and completely avoids these issues. It achieves a sort of pure and perfect state, whereas nothing else creates a perfectly symmetrical dynamic.” The irony of the “Old Lady” paintings, then, is based not on the supposed kitsch of the image, but rather on the idea that the cram school might be creating, in shortcut form, painters exactly like Wang.