In conversation with Jordan Richman

Betsy Johnson’s latest body of work unfolds like a game you’re dropped into without a tutorial. You don’t know the rules yet, but you feel them pressing in — unspoken, inherited, unavoidable. The images, the videos, the constructed realities within them flicker between control and chaos, between documentation and something closer to myth-making. Shot in Grimsby, a town that is both home and exile, the project is an excavation staged like a simulation — because sometimes the only way to understand the world you’re in is to reprogram it.

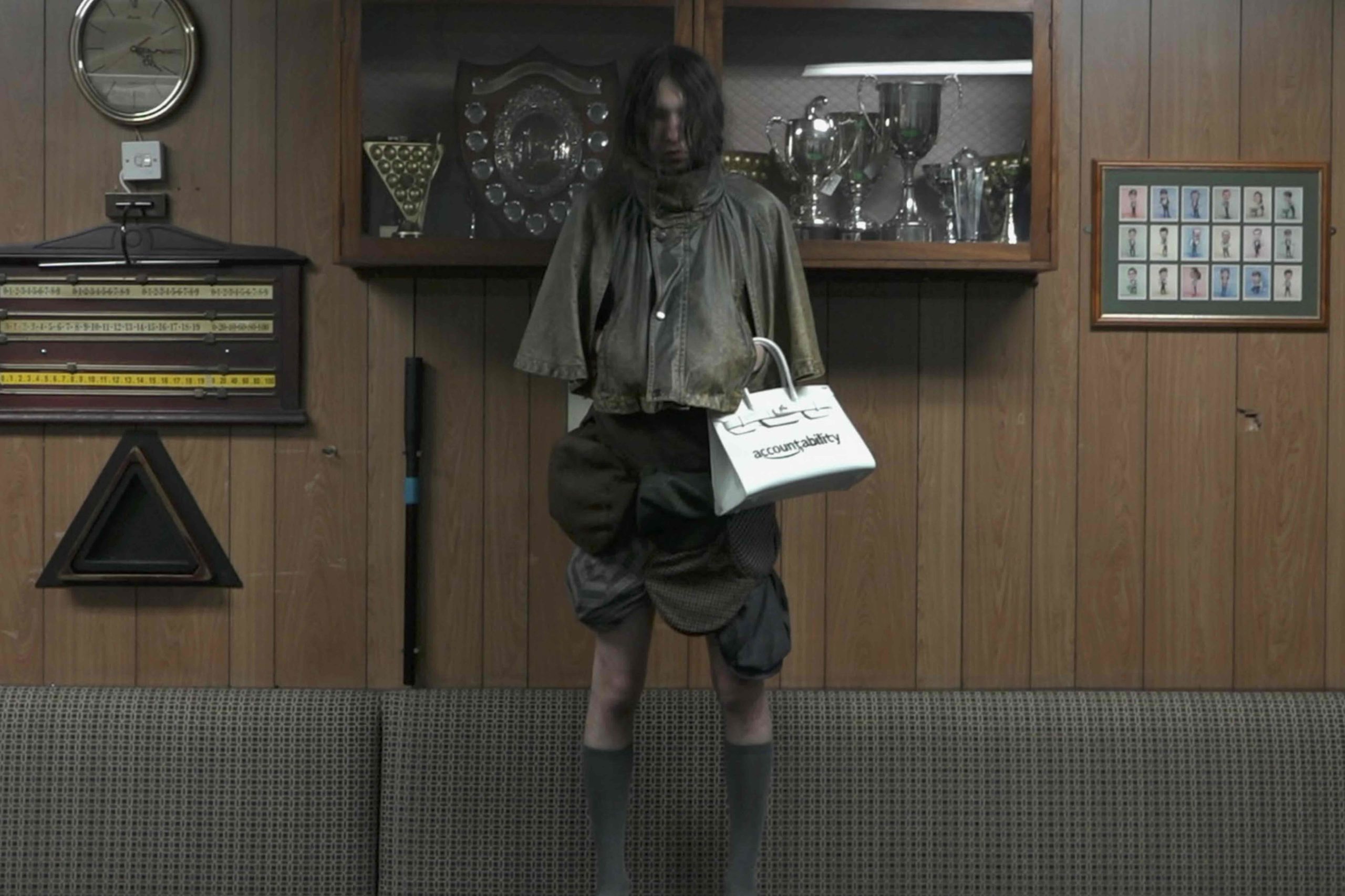

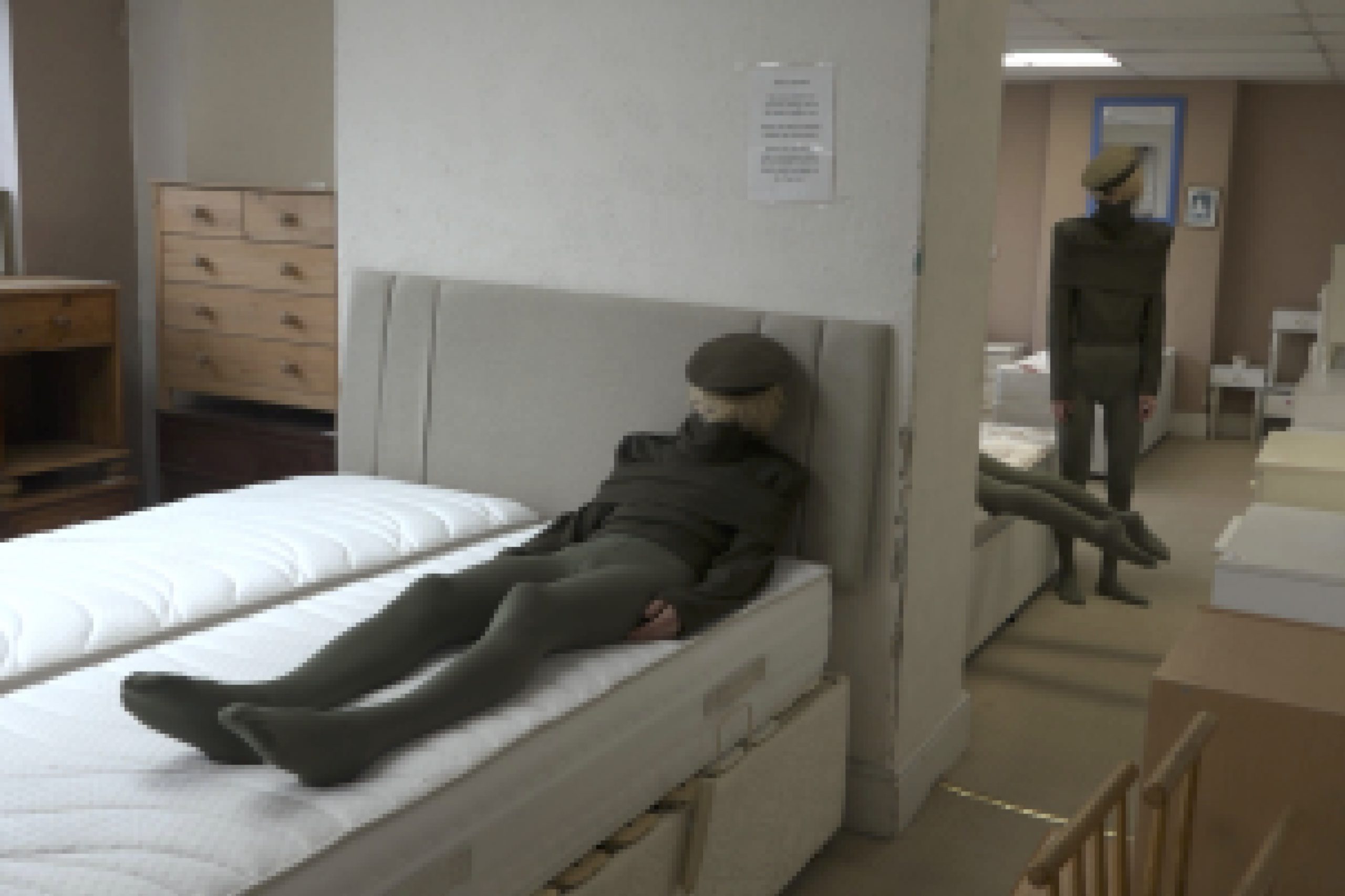

At the core of the work is an exploration of gender, identity, and performance—how femininity and masculinity are shaped by environment, expectation, and survival. The project dissects these themes through a visual language that pulls from the aesthetics of war games, suburban surrealism, and the uncanny familiarity of The Sims, blurring the lines between reality, simulation, and personal mythology.

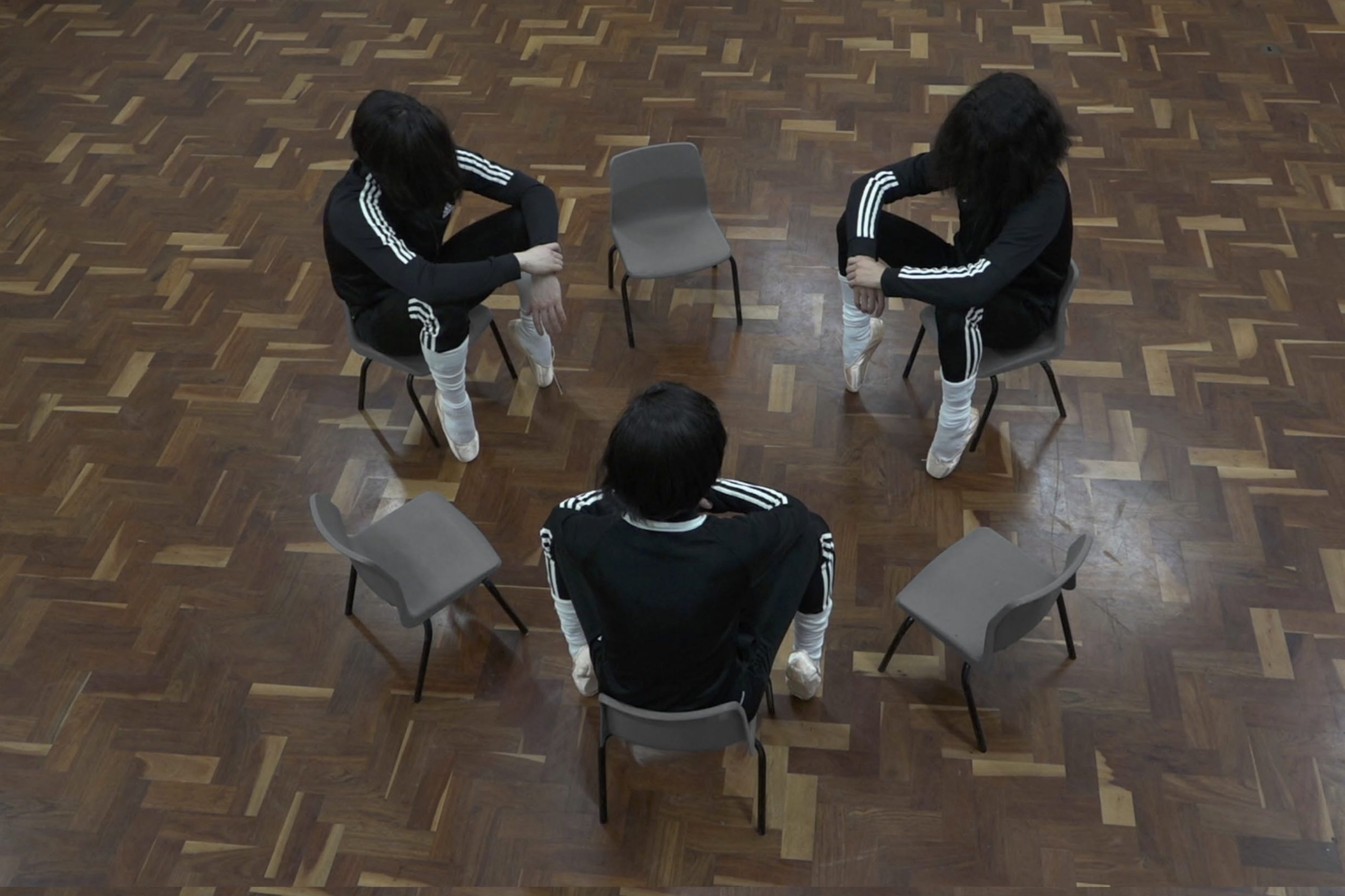

The videos are essential — first-person POV shots that feel like being inside a character’s head, sequences of ballerinas drifting through military surplus stores, the choreography of combat and dance collapsing into one. It’s a way of mapping out the tensions that exist between tradition and transformation, between the roles we’re assigned and the ones we try to script for ourselves. The sense of isolation is immense, but it’s not static. It moves, shifts, reloads.

For Johnson, this project was an experiment in letting go. Usually, she works with precision, with a clear vision of what each frame will be. This time, she let the images and footage accumulate, layering them like artifacts, like evidence. The result is a fragmented world that feels more real because of its fractures — a story that refuses to be neatly told.

The print version is only a fraction of the full project. The real experience — the full immersion — lives in the wider digital portfolio, where the layers of footage, the shifting perspectives, the recursive loops of war, gender, family, and escape can play out. Because that’s what this work is: a game you can’t win, a simulation with no exit, an afterimage that lingers long after you’ve looked away.

Jordan Richman: What the fuck is Grimsby?

Betsy Johnson: Grimsby is home now. It used to be everything I was trying to get away from, and now it’s everything I try to go back to when I feel something is missing in my work, the industry, or my medium. Until I was twenty, it was all I was running from. But yeah, it’s home. It’s in Northeast England. And yes, it’s as grim as it sounds – but there’s so much charm in how grim it actually is.

JR: Grimsby is home and home is where the heart is.

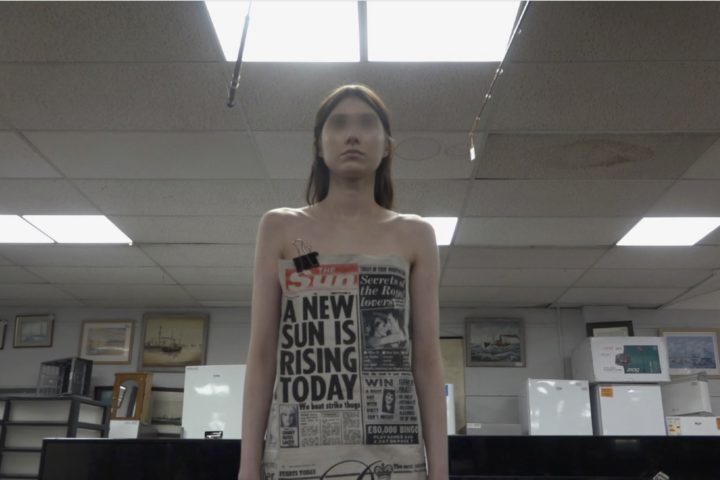

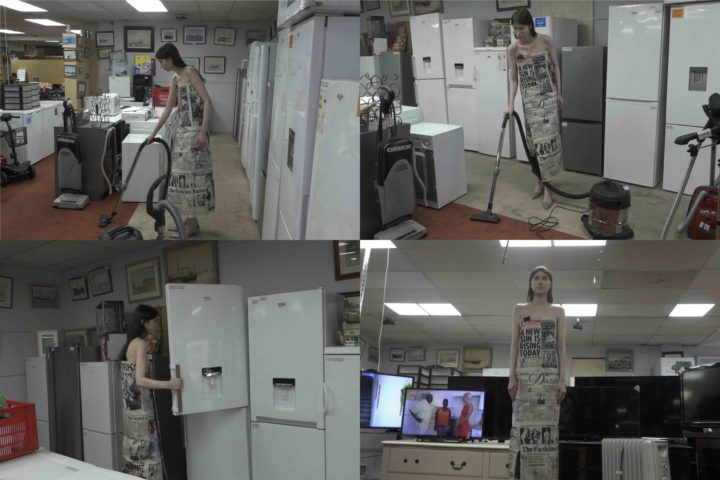

BJ: Family is at the center of this work, but unlike my usual approach – where everything is precise, planned, and nothing is left to chance – this was one of the rare times I just let go. I got all the ingredients there and let things unfold. It became about the tensions between femininity and masculinity, like when we shot in a Cash Converters and had this girl robotically interacting with a home environment. It’s hard to fully articulate how family connects to it all, but it’s there, woven into everything.

JR: Cash Converters are pretty grim.

BJ: So much of my work is about precision and decision-making, but none of that thought process went into why we shot at Cash Converters. I guess that’s just where you end up when you let go. So much of home is about taking places that hold a negative association and re-experiencing them – letting the work just happen.”

JR: How did you scout the locations?

BJ: It’s actually the gym where my cousin works, and every single location we used was through a family member – letting us in, sneaking us in, giving us the space to do our thing. What I love about shooting at home is that no one has really shot there before. No one in that world is thinking about art, fashion, or architecture, so to them, it all just feels super exciting.

JR: Is there more to Grimsby then you were able to capture?

BJ: I literally want to shoot a whole book back home. We were only there for four days but we captured so much content that we could’ve stayed for months and still kept going. That’s why we created the webpage – there was just too much to fit. We even struggled to narrow it down to eight spreads for print; it was really challenging.

JR: Did growing up in a military family develop your severe aesthetics?

BJ: A lot of people where I’m from enlist – my dad was in the military, all my uncles too. It’s just a thing, a military family. It’s funny how the things you grow up around suddenly seem ‘cool’ later, but to me, it’s still kind of strange. I wouldn’t say the worlds we inhabit now are directly connected to military culture, but the way I communicate and approach projects can feel a little militant. Sometimes I feel like a closeted artist in this weird military environment – but at the same time, we do have a bit of an army going on here. It’s nice.

JR: The essay feels stylistically like a simulation. Do you think you are living in a simulation?

BJ: I definitely think we’re living in a simulation. I went through a really difficult year where I genuinely believed I was in one – it was trippy. Everything felt too on the nose, too perfectly timed, like a constant state of oxymoron. It was a confusing way to live, like someone was pulling the strings, having fun with my every move. It was too strange to be real. But yeah, we’re definitely in a simulation.

JR: Have you seen the meme of an image of the Burj Kalifa and above it written “$1.5 Billion,” and next to it the GTA VI videogame cover and above it written “$2 Billion”? It’s about how the production cost of the videogame were more than the construction cost of the world’s tallest tower. With these developments soon we won’t be able to tell the difference between reality and computer generated graphics.

BJ: The whole point of escapism, I feel like, is that — wasn’t it Steve Jobs who said the reason he developed the MacBook was because he wanted it to become an integral part of people’s lives? It had to be seamless, a natural part of the experience. But the whole point of escapism, especially in video games, is to escape and feel a drastic shift from reality. So when you make escapism a seamless part of your daily life, where does one begin and the other end? When do we start living inside the escapism? It’s like people who live on drugs all the time — when do they come back to reality? If it becomes too seamless, shouldn’t it feel like a jolt, both visually and experientially, to snap you back?

JR: Gender performance and expectation are also major themes in the essay. How did your sisters and brothers experience influence the way you approach your own gender?

BJ: My gender experience is definitely influenced by my upbringing and the expectations placed on me growing up. I was the youngest, the only girl, in a very military household in Northern England. My dad was very traditional, and my mom had a pixie cut, didn’t wear heels, and wasn’t very feminine. It was a very masculine environment — no makeup, no fashion, no dresses, nothing traditionally beautiful. But in a way, that’s shaped who I am. My Grandpa was always there, we’d watch the news or documentaries, just experiencing life as it was. It was tough, but it influenced how I approach gender performance and expectation.

JR: Do you see similarities between combat and dance?

BJ: I think that mix of combat and dance reflects my inner monologue. I’m a really dramatic person, but I’m also very much in my masculine, and the duality between the two has always fascinated me — both within myself and in the relationships I have with my family. There’s always this harsh contrast, and I feel like I’m the only one in my family with these influences fused into who I am. So when you see them visually contrasting in my work, it’s something I really enjoy playing with — the harshness of one thing against the femininity of another.

JR: There is a strong sense of isolation throughout your work.

BJ: I feel really isolated within myself, and I think that comes through in my work — it’s probably a reflection of how I’ve always felt. As for Grimsby, yeah, it feels isolated too. It’s the last stop on the train, the end of the line. There’s a motorway that goes to Grimsby, and it doesn’t pass through anywhere else — it’s a destination, not a stop along the way. You’re either going there or you’re not. It’s very isolated from everything.

JR: And growing up in Grimsby you also felt very isolated from the rest of England?

BJ: I was trying to funnel all my creative expression through literature and performance — doing drama, theater studies, English literature, and sociology. I was following my thoughts down those paths, not realizing that fashion and art were other lanes I could access. That’s why I wasn’t exploring them. I didn’t think I could break into the art or fashion world. I was in fucking Grimsby. Then I went to Manchester, and it still felt like it was light years away from where I could go. It seems stupid now, but at the time, I didn’t think I could go to London. London felt like such a far-out reach for me six years ago. It’s crazy to think about now.