Two phrases reverberate like battling incantations throughout Virgil Abloh’s exhibition at ICA Boston, both from the video Peculiar Contrast, Perfect Light (2021): “Make space for me,” the voiceover implores, admonishing cultural gatekeepers to allow more Black designers like Abloh to ascend to positions of power. Then, in the same breath, a demand: “Make it up to me,” the voice insists, with “it” referring, ostensibly, to the centuries of violently stolen land, labor, and life that formed contemporary racial distributions of wealth.

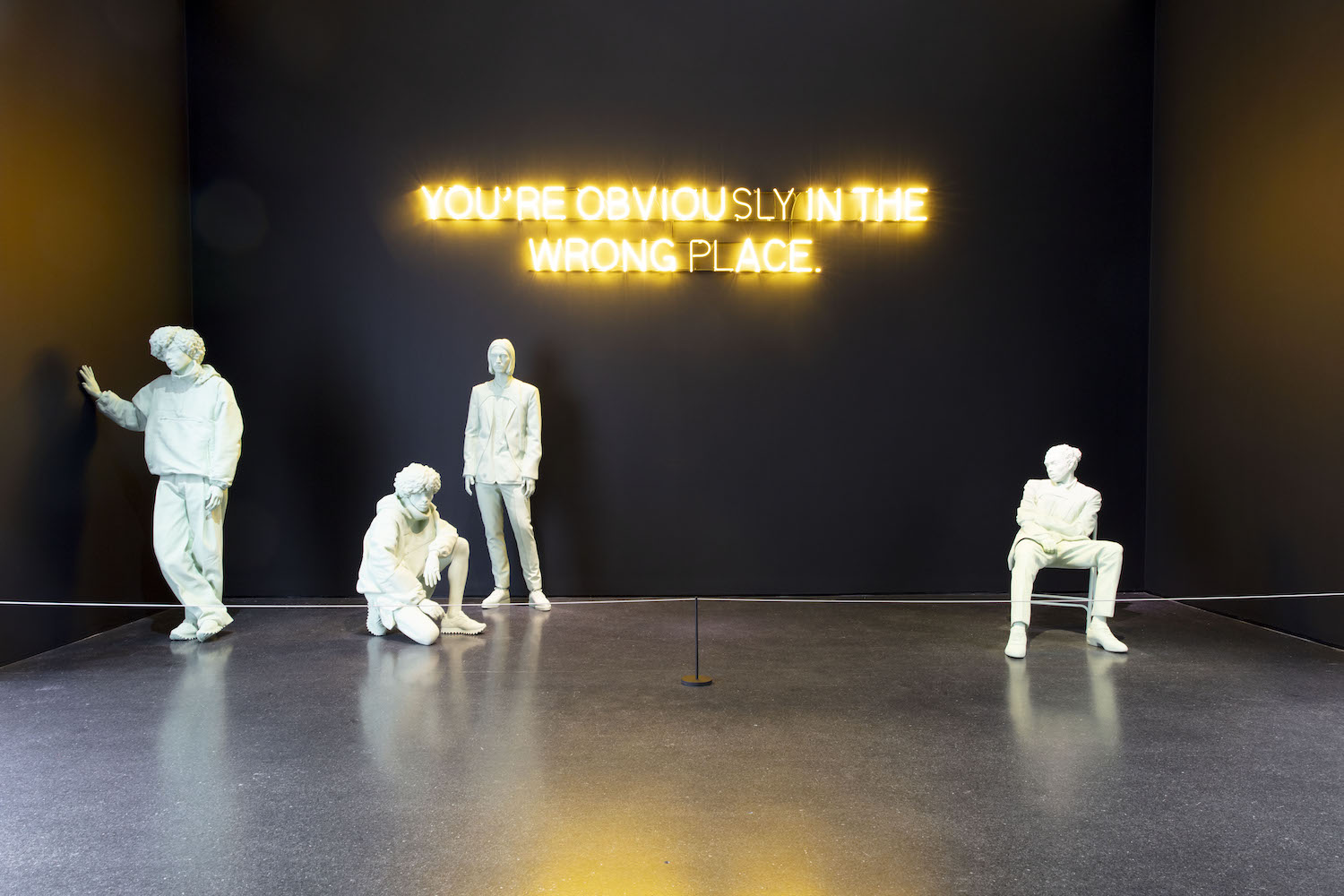

“Figures of Speech” opens by carving out a space for Abloh in the art museum, situating the multi-hyphenate creative as an inheritor of both Marcel Duchamp and Kazimir Malevich. The exhibition’s first room features a Juergen Teller photograph of Abloh wearing a sweatshirt inscribed “R. Mutt 1917,” positioning Abloh himself as an authored readymade, as well as a cultural producer authorized to appropriate in the name of art. On the opposite wall hangs a black monochrome painting, an homage to Malevich’s utopian communist vision: on the precipice of the Russian Revolution, the painter declared his black monochromes “economic surfaces” prefiguring the moment of “freedom […] after our ideas about the organization of solids have been completely smashed.”1

For Malevich, collapsing the distinction between figure and ground was an explicitly communist act; Abloh’s black monochromes insistently reinstate figuration in the form of advertising text. In the exhibition’s final room, two monochromes function as billboards, the first marketing, simply, “television,” and the second bearing a phone number which the viewer can call to hear Abloh discuss his 2016 Off-White collection. The message is clear: today, the collapse of figure and ground provides only a smooth surface upon which to articulate branded content.

Abloh emphatically reiterates this reimposition of figure onto ground in one of the exhibition’s most unnerving works, “FASHION” (2020), a nearly fifty-foot wallpaper of a street scene in Accra, Ghana, where Abloh’s parents lived before immigrating to Chicago. The photograph’s foreground is populated by cut-and-paste images of runway models wearing all-white designs; their bodies crowd out the Guyanese pedestrians to literally march into the museum space as life-size paper dolls. At the opening, museumgoers pointed out recognizable faces (Gigi Hadid, Kendall Jenner), whose images, in proper Duchampian fashion, are valuable mostly for their ubiquity. The installation chillingly suggests that Accra provides an effaceable backdrop against which brand ambassadors become visible.

Abutting “FASHION” is Abloh’s take on the classic Louis Vuitton Keepall bag, which features a heavy, safety-orange chain. In the museum space, the chain secures the bag to its low pedestal; in a boutique, the curatorial text explains, it acts as a deterrent to would-be shoplifters. The motif is repeated in A Series of Events (2019), an installation of cylindrical ceramic vessels whose long chains trail down their safety-orange plinths. The reference to shackles used to transport captured Africans to slavery in the Americas is unavoidable; here, the tension between making space and demanding repair reaches an impasse, with Abloh using the same visual cue to refer to both the violence of making people property and the securing of luxury goods from theft.

During last summer’s uprisings, Abloh condemned precisely the sort of smashing of solids that Malevich celebrated: when protestors broke glass storefronts to claim luxury as their own, Abloh posted on Instagram that they should consider the goods they had taken “tainted.” (He backpedaled shortly thereafter.) “Figures of Speech” presents a more ambivalent attitude toward the magical power of thievery. If, in practice, Abloh insists upon securing luxury goods to pedestals, in Peculiar Contrast, Perfect Light, stealing is figured as a creative act. As a Louis-Vuitton-clad Yasiin Bey (Mos Def) twirls and pirouettes, poet Kai-Isaiah Jamal recites, “You know, when all the girls […] take things from runways or ballrooms, it’s not stealing, or robbery, or looting. It’s stepping into a fantasy that shouldn’t be a utopia, but just a living right. I think, as Black people […] the world is here for our taking, for it takes so much from us.” In the video’s most thrilling moment, Bey does precisely that, gracefully lifting a metal briefcase from the floor before losing himself in a crowd of briefcase- and bag-swapping thieves.

The boundaries Abloh seems most willing to smash are those between creative disciplines and commodity markets. Perhaps, as the ultimate appropriator, he might push Duchamp’s vision one step further, dissolving the final remaining boundary between those things that cost money and those that are free. I imagine his next exhibition emblazoned with instructions to “steal this show,” and I imagine an artist who might mean it.