Tavares Strachan

Bahamas pavilion

Art and travel are like two old lovers who do not always get along. Bruce Chatwin may have known this when, while employed at a famous London auction house, he resigned due to vision problems. An ophthalmologist had advised him to stop looking at paintings so closely and instead to turn his gaze to the horizon; he left art and thus began his life as a traveler.

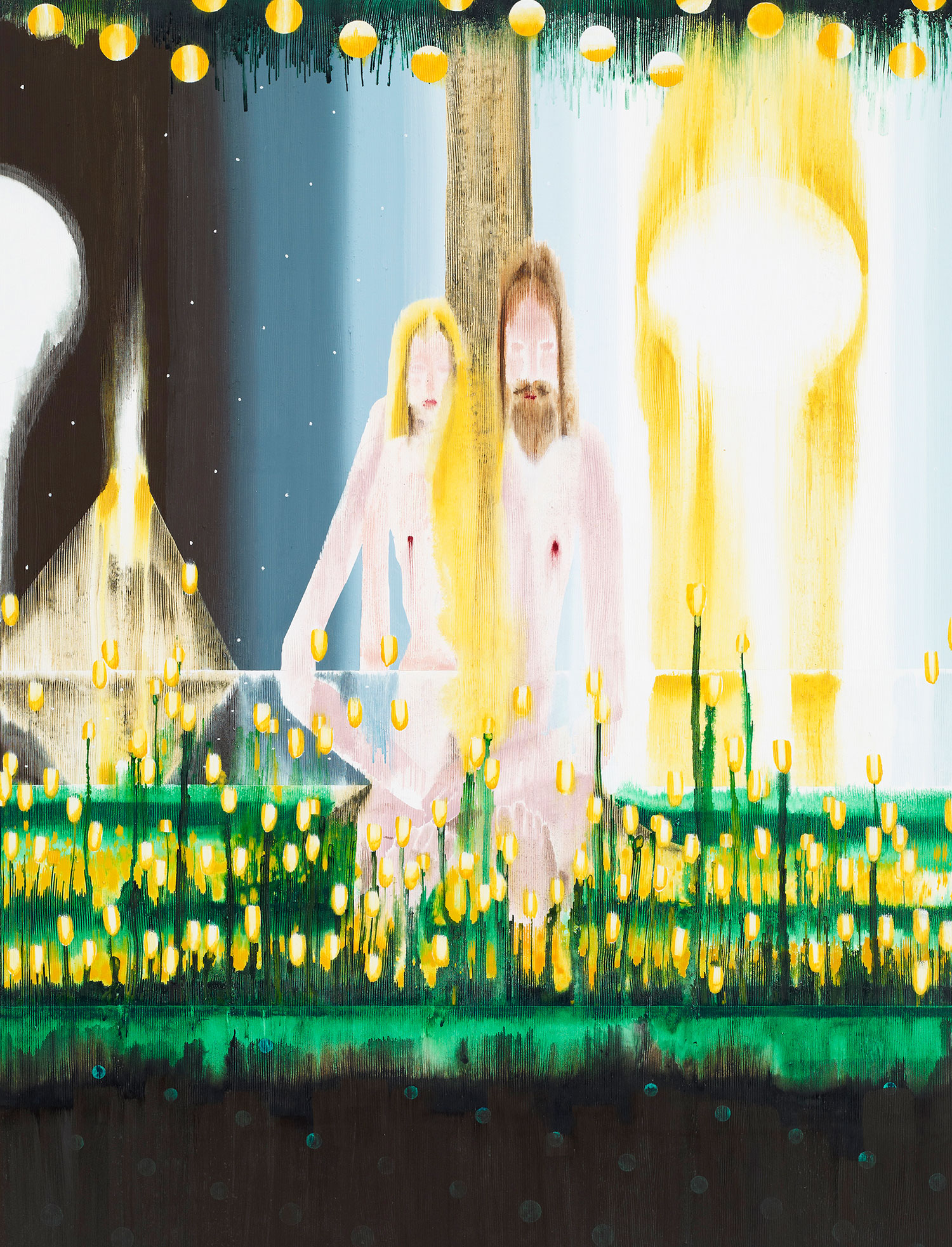

Tavares Strachan, born in Nassau in 1979 and now based in New York, considers travel in its different guises: exploration intended as the heroic conquest of the horizon and uncharted territories, the hunger for adventure, as well as a necessity when problems arise. Unlike Chatwin, who failed to merge his passions for art and travel, Strachan treats the trip — especially exploration — as a metaphor for life and art, with all the dichotomies that this implies. Think of a Caribbean in the North Pole: Strachan plunges us into a multi-sensorial realm in which cold and heat, the Far North and the Far South, coexist.

The protagonists of this narrative, which seems to unfold in chapters, are Robert Peary and Matthew Henson Alexander, the two Americans who in 1909 explored the North Pole. Entering the pavilion, the effect of white neon is alienating. From the darkness emerges blocks of ice, snow-white canvases populated by tiny signs that make up the shape of a bear, a bird, the two explorers, like tracks in the snow. On a monitor, we see and hear children from an elementary school in Nassau singing an Inuit song before disappearing, as if swallowed up by something. Lightboxes depict the “Polar Eclipse,” a phenomenon that does not exist in nature. These elements suggest the possibility of an unprecedented meeting, a way to replace the sun with ice, to subvert the laws of nature. And when nature fails to accommodate such meetings — the North and South Poles will never meet, and ice will always melt in the light of the sun — it is man who is able to facilitate these meeting points.

by Daniela Ambrosio

Shirazeh Houshiary

Torre di Porta Nuova, Arsenale

Sound is a schizophrenic medium, as constraining as it can be liberating. Its immersive condition has fostered the transformation of sonic material into weaponry, deployed as barriers and repellents within today’s society of control. Yet the medium’s liquid qualities, which enable it to spill over categories, seep under firewalls and slip between memories to find us and move us, offer aesthetic and personal avenues for contemplation.

Among the cacophony of artworks vying for attention during the Venice Biennale this year, Houshiary’s immersive sound installation Breath (2013), inside the majestic 35-meter-high Torre di Porta Nuova at the edge of the Arsenale, was remarkable for its untimely composure. Many artists in the Biennale drew from the frenetically charged rhythms and images of media and social networks as foundations for an analysis of the construction of our identities and our relations with the world around us. Giorgio Agamben in his essay “What is the Contemporary?” remarks that to be contemporary and belong to one’s time, one must neither really coincide with it nor fit to its demands; that it is in this sense of being out of phase that enough perspective can be acquired in order to truly see contemporaneity. Housed within a specially constructed chamber clad in black felt, Houshiary’s work steps determinedly out of time, coupling the meditative chants of Muslim, Buddhist, Christian and Jewish prayers with the delicate patterning of the vocalists’ inhaling and exhaling breaths portrayed on four video screens. As with so much of her practice, the impetus is as microcosmic as it is macrocosmic. Breath traverses the accelerated flow of contemporary times by focusing on the life-affirmative quality of taking a breath for survival and exhaling what might be your last. Yet it also highlights the simultaneous unity and multiplicity of the collective, the vocalistst and by implication the four world religions evoked.

Outside the chamber Houshiary presents the intense torsion of Eclipse (2008), a large reflective aluminum sculpture, as well as three delicate paintings: Bruise (2013), Pneuma (2013) and the artist’s largest diptych to date, Between (2010-11). The paintings are particularly conversant with Breath, not least because the ancient Greek meaning of “pneuma” is breath, soul or spirit, and because “between” is evocative of the connecting spaces within people — the jointly shared moment that give breathing its wider collective meaning. These are painstakingly created works, born from hours of patient coating of pigment layers on canvas, upon which Houshiary then traces intricate pencil filigrees composed of two sentences — “I am” and “I am not” — overlaying them hundreds of times until oblivion is reached. Their meaning thus disappears; indeed, for Houshiary words are dangerous things, constraining experience.

These paintings are remarkable for their sense of internal rhythm, depicting what appear to be processes rather than finite configurations. These are processes that relate as much to the endoplasmic dynamics of our body as they do to the galactic forces around us — both of which are energies beyond our complete control. At a time when knowledge is everything in our world, and when almost everything is spoken and codified, Houshiary’s works take us on a journey of silent revelation, along a path of interconnectedness between what is unknown within us — our pneuma — and the overwhelming powers of the cosmos. This is a journey beyond the word, beyond the certain, and which can only take place within the search for the intangible and the invisible within and beyond us.

by Katya Garcia-Anton

When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969 / Venice 2013

Fondazione Prada, Ca’ Corner Della Regina

To recreate Harald Szeemann’s iconic exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” more than forty years later is quite a challenge. But Germano Celant went even further than that. Not only did he succeed in gathering ninety percent of the works that were on display at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, he also transposed, with the help of Rem Koolhaas and Thomas Demand, the original exhibition spaces to the Ca’ Corner della Regina, an 18th-century palazzo that hosts the Prada Foundation in Venice. The intent was never to find a white cube-type of space to rebuild the show, as Celant explained to Erik Verhagen: “Reconstructing it as it was would be an illusion, because you can’t turn back the wheels of history, or translate the exhibition — and thus betray it — into an adaptation that is not the same.” This might sound irreconcilable with the very purpose of the project, which was to “exhibit an exhibition, like the one curated by Szeemann.” The intriguing result goes way beyond a simple reconstruction of the show. The transposition of the Kunsthalle within the Ca’ Corner creates the strangest exhibition space one could imagine, bounded by white wooden slats and crossed by architectural elements — the walls and columns of the palazzo — that act like parasites. This has dramatic consequences for the works of art, as for instance Bill Bollinger’s Screen Piece and Pipe Piece (both 1968), which are squeezed against pillars, Carl Andre’s 36 Copper Square (1968) on display between two doorways, and Barry Flanagan’s Two Space Rope Sculpture (1967), now turned into a “three-space” piece. But it also affects the way the (very numerous) visitors see the exhibition, as there is no easy way to go through it; being a guard at the Prada Foundation will be a tough job this summer. Presumably the only solution for preventing accidents with Richard Serra’s “prop” works is to place a thick rope around them — something that seems inconceivable at first. Celant forces us to wonder whether it makes sense to display these historical pieces in this way, putting the emphasis on the freedom of the curator. His gesture seems iconoclastic at first glance, but produces the exact opposite effect; even under these conditions, the works maintain their integrity. Last year, Jens Hoffmann (who is a contributor to the catalogue) curated a show called “When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitudes” at MOCAD, presented as a “sequel to, and a re-evaluation of” Szeemann’s exhibition. Floor plans, images and a large-scale model of the Kunsthalle Bern were presented along with pieces by “artists working in relation to the history of Conceptual art” or else responding directly to the 1969 event. If Hoffmann and Celant share a similar interest for “When Attitudes Become Form,” they look at it from two different, complementary points of view: the former focuses on the artworks themselves and their potential influence on creation today, while the latter studies it as a founding moment in the history of “exhibition setting,” referring to Terry Smith’s Thinking Contemporary Curating. For Celant, it was thanks to Szeemann that “the curator found a creative dignity on his own.” Considering the very prominent position of the curator in the contemporary art scene today, there is no doubt that Szeemann’s message has been heard.

by Pierre-Yves Desaive

The Middle East Pavilions

Kuwait, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Turkey, Bahrain, Syria, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Iran

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the collective Middle Eastern presence at the Venice Biennale was that so many participants were there at all. Barely a decade ago, artists of Arab and Persian origin were still regarded by many west of Suez as a global novelty. How times have changed. Middle Eastern art has never been so strong, vital and globally visible as today.

This year’s Biennale featured a record number of artists from the region in both pavilions and collateral projects. Pavilions from Kuwait, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Turkey, Bahrain, Syria and Egypt were all present. Hailed and applauded, rightly so, for its thrilling scope of vision and satisfying heft, Massimiliano Gioni’s “Encyclopedic Palace” nevertheless failed to pick up on any significant contributions from the East. No matter. There is always next time.

Instead, we head to the Arsenale, to the Pavilions of Bahrain, Turkey, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates. The latter is the first Gulf state to have entered the Biennial, in 2009. Now, following two rather unremarkable presentations, the UAE has presented a solo exhibition by conceptualist Mohammed Kazem, one of a tiny coterie of like-minded Emirati artists who have been quietly developing and archiving their works for over two decades now. Kazem’s Walking On Water, an installation that envelopes the viewer in a near-360-degree seascape with an undulating horizon bathed in deepest aquamarine, is part of a decade-old project in which the Emirati artist once flung wooden boards into the Arabian sea, off the coast of Fujairah. He has long been fascinated by the possibility of losing oneself and one’s identity through the metaphor of the sea — a preoccupation perhaps related to a near-drowning incident in childhood. This low-key yet deeply affecting work has set the bar high for future UAE participations. Given they have just signed up for a 20-year lease on their pavilion, it will be interesting to see who comes next.

Across from the UAE is the Pavilion of Turkey. Understandably, video/installation artist Ali Kazma might have been feeling a little sidelined personally, as protests in Gezi Park began around the time of the opening of the Pavilion. A spontaneous protest in San Marco took place the following day. In Resistance, Kazma focused on one of the most incendiary platforms of cultural debate in the region — the human body, that bellwether of religious affiliation, cultural positioning and gender politics. Kazma showed a series of film installations dealing with bodies, bodies, bodies. Seen through a prism of socio-cultural intervention, the works vibrate with tension, ossified traditions, expectations and evolving strategies to either move towards restraining or revealing the body.

Nearby, the Pavilion of Lebanon also presented a work by a single artist (solo exhibitions tended to be the better pavilions this year). Akram Zaatari’s LetterTo A Refusing Pilot, curated by the peripatetic team of Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, demanded your time. For 45 minutes it gently took you through the early life of the artist via dream-like sequences and poignant evocations of innocence, family and tranquility — until the day in the summer of 1982 when an Israeli pilot was instructed to bomb the artist’s alma mater in his small hometown. Whether the pilot actually did ignore his commands to hit the school — and instead dumped his payload into the sea, as local rumor quickly had it — is almost irrelevant. The power of memory, personal mythology and collective narrative actively engages the viewer through Zaatari’s almost forensically presented scraps of nostalgia — letters, diary entries, photographs. It is as if he is challenging us to believe the veracity of the contested incident. (The pilot did disobey his commands, incidentally — only for the school to be subsequently bombed by another fighter jet.)

Visiting Iraq’s Pavilion felt less like trudging wearily into a typical pavilion and more like collapsing gratefully onto a sofa in a much-loved relative’s home. Tea was on hand as guests prowled the airy rooms of the apartment in Ca’ Dandolo, near San Tomà, filled with art sourced from deep within the beleaguered nation. More a sum of its parts, constructing a narrative of hopeful, cautious optimism and renewal deep within the complex national fabric of the nation, it’s an engaging affair with a stand-out contribution from photographer Jamal Penjweny. His “Saddam Was Here” series of photographs depict ordinary Iraqis in various social and cultural permutations, holding aloft portraits of the late, unlamented leader.

In addition to official pavilions, this year’s Biennial included a record number of collateral activities by Middle Eastern institutions. These included Edge of Arabia’s fizzy presentation of young Saudi artists. Done in typically grand style, “Rhizoma” was a testament to the organization’s relentless promotion of young art from the region. Another terrific show was “Love Me Love Me Not” by Azerbaijan’s Yarat Foundation, which featured 17 artists from Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, Russia and Georgia. These included old stalwarts such as Farhad Moshiri (who has evolved wonderfully from the crowd-pleasing, Middle Eastern auction star) and one of Central Asia’s most prolific artists, Jameel Prize nominee Faig Ahmed. Also present were the irrepressible Slavs + Tatars, a collective who work with linguistics, wit and common, collective mythologies from this amorphous, culturally complex part of the world. Their typically idiosyncratic installation Molla Nasreddin the Antimodern (2011) managed to present an appreciation of the 13th-century Sufi poet Molla Nasreddin in the form of a playground ride. And the insanely popular Ali Banisadr, an artist so much in demand by the cognoscenti at the moment that his waiting list is rumored to be worthy of framing in its own right, presented his largest work to date, a colossal triptych that referenced the Zoroastrian symbolism of fire and light.

The two artists representing the non-state state of Palestine both had impressive global credentials: Bashir Makhoul is the head of the Winchester School of Art in the UK, and Aissa Deebi is the founder of ArteEast in New York. No doubt presenting a classification muddle for organizers, it was presented in a quiet side street near Accademia. Wittily entitled “Otherwise Occupied,” the two artists participated with two very different projects. Makhoul invited visitors to literally construct a city from a stack of cardboard boxes. This prompted the unprecedented sight of groups of stylish art mavens on their hands and knees, wielding Stanley knives and enthusiastically carving boxes that joined the tottering mountains leading down the garden path to the entrance. A commentary on the fundamental issues of land and settlements in the artist’s homeland, the interactive installation brought a rare and pointed wit to an altogether tragic reality.

It was with work such as this that I really felt an evolution, a maturity and a new dynamic in the range of work coming from what we rather sloppily tend to refer to as the MENASA (Middle East, North Africa and South Asian) regions. To this we could add a very necessary “CA” to reflect the growing accumulation of contemporary art coming out of cities in the former Caucuses. After once existing in the curatorial margins, this year’s Bienniale shows that the contemporary art of the Middle East is finally standing proudly in its own right.

by Arsalan Mohammad

Kamikaze Loggia

The Georgian pavilion

After the fall of the Soviet Union and the resulting chaos of the 1990s, the “kamikaze loggia” — extensions of existing buildings constructed in order to expand living spaces, built in defiance of building regulations — began to appear in Georgia’s capital city of Tbilisi. It seems that such structures can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when these special wooden buildings were built on the slopes of mountains.

Walking through the Arsenal we come across a wooden frame that extends from an existing building — a structure driven into the mud of those rainy opening days of the Biennale. This unique pavilion was designed by artist Gio Sumbadze, founder of the collective Urban Research Lab (URL), which documents the relationship between Soviet infrastructure and the decline of Marxist ideology. An example of parasitic architecture and an emblem of the unauthorized dark years of the post-Soviet era (dark not only in a metaphorical sense, given that electricity was in short supply), this model for do-it-yourself urban planning evokes both past and future, good (the idea of home, shelter) and bad (the word “kamikaze” evokes suicide bombers). Joanna Warsza, a curator attentive to socio-political developments and the urgent needs of the public, organized the participation of the Bouillon Group, Thea Djordjadze, Nikoloz Lutidze, Gela Patashuri with Ei Arakawa and Sergei Tcherepnin, and Gio Sumbadze. In other words, she brought together architectural elements, installation, performance, poetry and sound art to create a deliberately diverse perspective that reflects the religious and cultural diversity of Georgia. This multiplicity is especially well represented by the Bouillon Group, whose performance Religious Aerobics translates the gestures of the three main monotheistic religions in Georgia — Islam, Christianity and Judaism — into aerobic exercises to be repeated like a mantra. Implicit is a playful critique of the obsession for the perfect form, as well as the advent of a strongly religious Georgia in reaction to the Soviet era, when religion was taboo.

Thea Djordjadze hates loneliness. She uses materials like steel, polyurethane foam and glass to create the individual words of a speech yet to be given. The result is concrete and abstract at the same time, because what we see are not just metal frames, glass bottles and pieces of cloth, but also places with rarefied atmospheres, without a name.

Performer Nikoloz Lutidze presents Euroremont — a neologism that suggests restructuring based on the European model. It consists of photographic collages, receipts, notes and calculations to document the conversion project of a space from Soviet to European — and therefore democratic and modern.

Gela Patashuri, Ei Arakawa and Sergei Tcherepnin have previously worked together. On this occasion they interpret a musical composition using the 277 musical poems that Patashuri’s father wrote from 1978 to 2003, the year of his death. Here, the poem becomes a voice for recounting the country’s political and social changes in the form of a series of songs played by radio-sculptures.

The Pavilion of Georgia reflects the desire to build and self-destruct, the search for a vital space to create and dismantle at the same time, an obsession for something that is near and yet far away, on the other side of the wall, in the West. And now, after the end of everything, we realize that Stalin is not dead. He’s just sleeping.

by Daniela Ambrosio

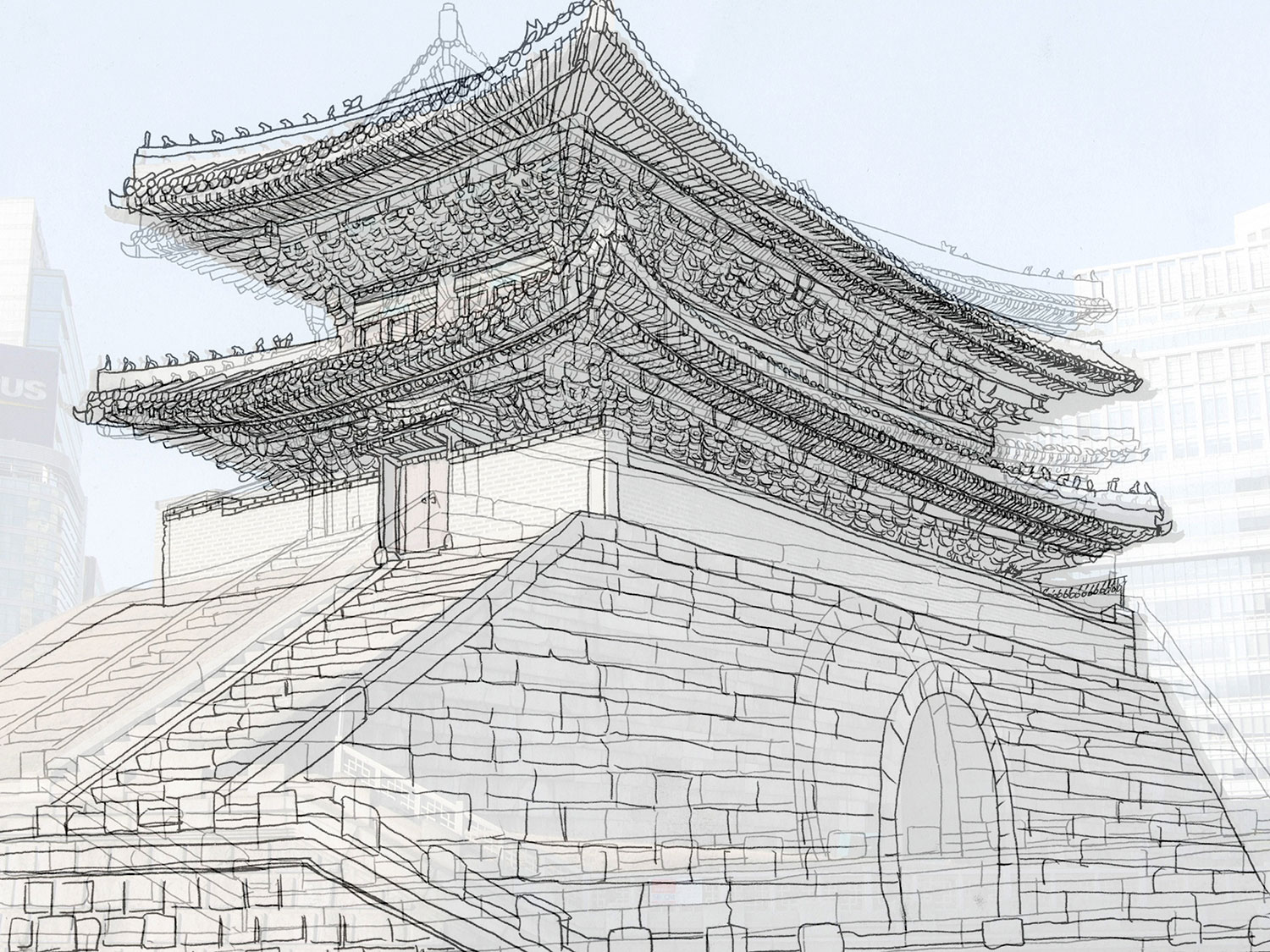

Asian Pavilions at the Venice Biennale: Studies in Collaboration

Japan, Indonesia, Taiwan, Korea, Thailand

What happened in Japan after the tsunami? This very simple question demands a very complex answer. As infrastructures recover, how are the psychological aspects of social relationships changing? Koki Tanaka explores the post-tsunami situation from a unique perspective in his new project for the Japanese Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Focusing on the idea of collaboration, Koki Tanaka created five different projects that involved asking communities in Tokyo to investigate their memories of how people worked together to overcome the crisis after the tsunami. Intelligent and touching, sublime and simple, Tanaka has developed an unpretentious way to address a very complex and delicate social context.

In the Indonesian Pavilion, curators Rifky Effendy and Carla Bianpoen developed a narrative response toward their country’s current political context. The theme of “Sakti” provides a framework for works by five artists: Albert Yonathan Setiawan, Eko Nugroho, Entang Wiharso, Titarubi and Sri Astari. Most of these artists came up with large-scale installations that lend the interior spaces a dramatic ambience. The works juxtapose many different visual elements of Indonesian culture, but all strongly emphasize the aspect of traditional craftsmanship. Various spiritual symbols strongly resonate within a performative chaos with darkly humorous political overtones.

While the Indonesian Pavilion plays with representations of its national identity, Taiwanese curator Esther Lu chose to work across borders by inviting artists from different backgrounds — a strategy also used in the German Pavilion. “This is Not A Taiwanese Pavilion” presented works by Chia-Wei Hsu (Taiwan), Bernd Behr (Taiwan/Germany) and Katerina Šedá (Czech Republic).

Near the entrance to the Arsenale, Hong Kong artist Lee Kit showed his ability to connect the idea of space with a subtle evocation of everyday memories. Visitors were invited to notice the changing details of a quotidian archeology as narrated by domestic materials. Hosted by M+ and curated by Lars Nittve, the Hong Kong Pavilion represents a new vision of a rapidly evolving cultural landscape.

The Korean Pavilion this year featured To Breathe by Kimsooja. Continuing an ongoing project, the New York-based artist transformed the exhibition space into a mirrored landscape that enables audiences to meditate on concepts of the self and its relationship to others. Within a small, darkened space, viewers were also invited to experience total darkness.

Away from the hectic Arsenale and Giardini is the Thai Pavilion, located near the Santa Lucia railway station. Presenting two artists, Wasinburee Supanichvoraparch and Arin Rungjang, the exhibition is curated by Worathep Akkabootara. Golden Teardrop, a work by Arin Rungjang, beautifully narrates the historical Thai era that gave birth to thong yod. It’s a story that begins about 700 years ago in Portugal and reveals connections between Thailand, Portugal and Japan.

Singapore decided not to mount a pavilion at this year’s Biennale, a decision that provoked much debate about how their government should distribute public funds for arts and culture. With their history of high-quality exhibitions in Venice, I missed their incisive yet humorous critical commentary on issues of identity.

by Alia Swastika