The international exhibition of the 53rd Venice Biennale, “Making Worlds,” opens on the 7th June under the directorship of Daniel Birnbaum. This edition also sees Carlos Basualdo take up the role of commissioner of the U.S. Pavilion. To find out more about what to expect this year, as well as what it means to be involved in Venice, Flash Art invited Daniel and Carlos to share their thoughts on the task in hand.

Michael Polsinelli: Daniel has presented an outline for the Biennale that aims to draw upon the lineage of contemporary art through the inclusion of some historical touchstones — the roots of the as yet unknown future branches of contemporary art. It is interesting in this respect that Carlos has selected one of the most influential artists in contemporary art history, Bruce Nauman, for the U.S. Pavilion this year. Perhaps you could begin by considering your respective starting points.

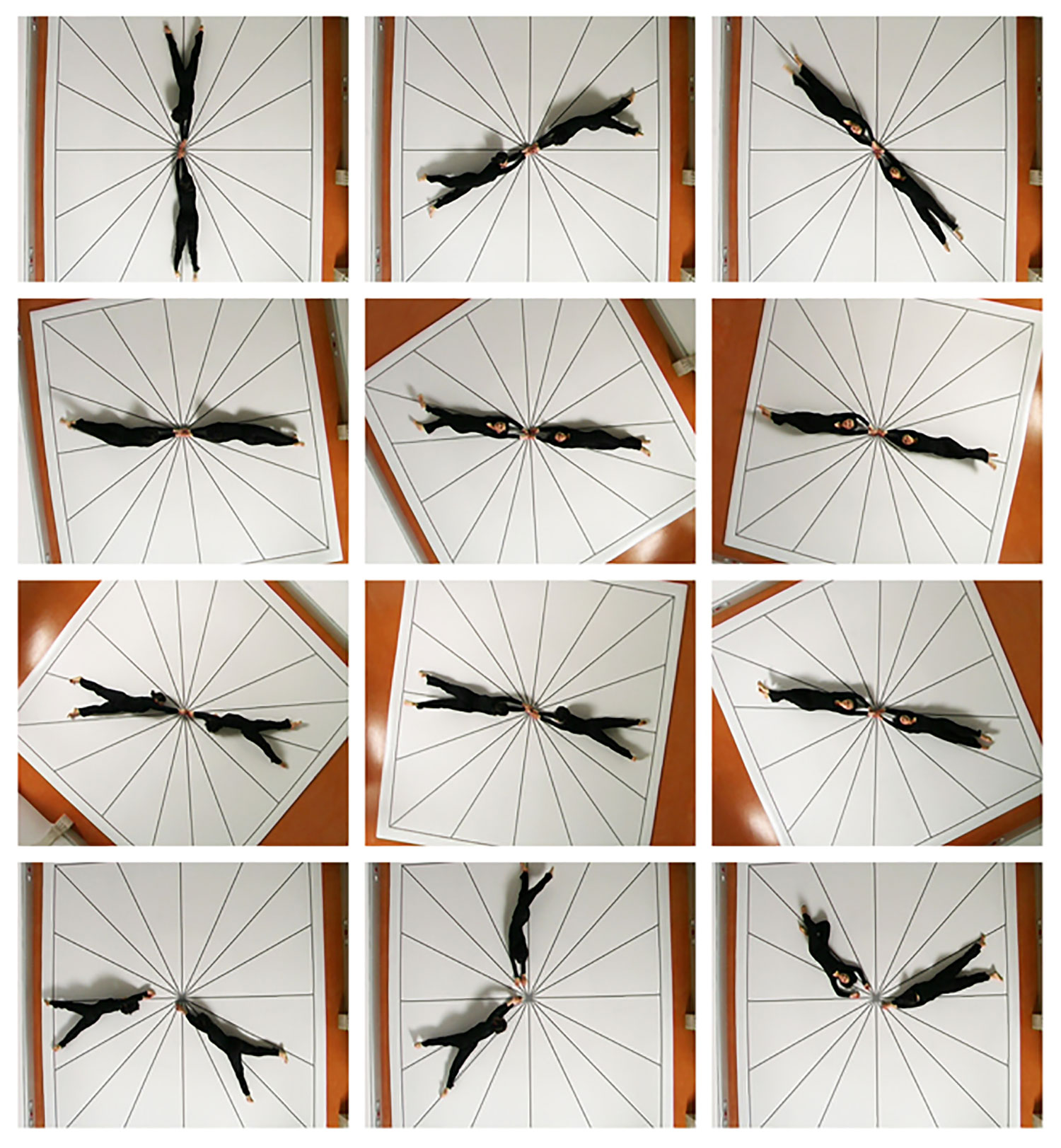

Carlos Basualdo: I have been teaching in Venice since 2004 but had never considered making a proposal for the U.S. Pavilion. Once I began to think about it, it made sense in terms of my relationship with the university. I was talking to Michael R. Taylor, who is the Curator of Modern Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the co-commissioner of the Nauman project, and we were both thinking hard about Nauman because the museum had recently finalized an acquisition of one of his early neons [The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967] and I had seen his Square Depression (2007) in Münster that summer, which was an older piece realized after more than 30 years and it was simply fantastic. I was curious about Nauman because I really didn’t feel like I understood his work as a whole — I wanted to learn more about the work. I thought that maybe Venice could tell me something about the work and the work could tell me something about Venice.

There will be two other sites for the show in addition to the Pavilion at the Giardini. One is the Università Ca’ Forscari on the Grand Canal and the other is the Università Iuav at the Tolentini. The intenition is to connect the universities to the structure of the exhibition. In the ’70s there was a very serious attempt to put the Biennale in very close relationship with the city, the people of Venice, the workers in Venice and Mestre. There were a number of very successful shows in this respect, but then it kind of simmered on the ’80s and then it was not attempted comprehensively again. It is a very difficult thing to do because of the determinations of the Biennale, but I felt the Pavilion could try that. To turn to you Daniel, I think it’s a wonderful proposal to move the Biennale archives to the Italian Pavilion because it will pave the way for collaborations of all kinds. How do you relate to that — is it something that interests you?

DB: This ambition is a key ingredient of what we’re trying to do. The idea didn’t come from me to establish the central Pavilion as a platform for permanent activities; it came from Paolo Baratta [President of the Venice Biennale]. I’m trying to give it an artistic dimension. For example, we’re building a bookstore by Rirkrit Tirivanija, we’re building a cafeteria by Tobias Rehberger and we’re doing an educational space by Massimo Bartolini. These elements may well last a little longer than this show. With all the things that happen in Venice — the dance, theater, music, architecture, film and art festivals — all the international interest in these artistic communities could really build an institution of a very different kind. Now we have the feeling that the Venice Biennale disappears and then has to reinvent itself from scratch every second year, but it should really be a place where there could be small shows, seminars, readings and workshops in an interdisciplinary fashion.

CB: What you are describing has many things in common with the experiments of the ’70s — the idea of permanent activation of the Biennale through an archive that is open and alive but also through the collaboration of different artists coming from different disciplines… Does it tempt you to do the next Biennale too?

DB: No, but it tempts me to be involved. We have plans that would not make me responsible for a second show — because I’m not so sure that is a good idea — but to be somehow involved more long term. This is actually part of my contract. Although not quite formulated yet, it could be that we start some sort of international art workshop.

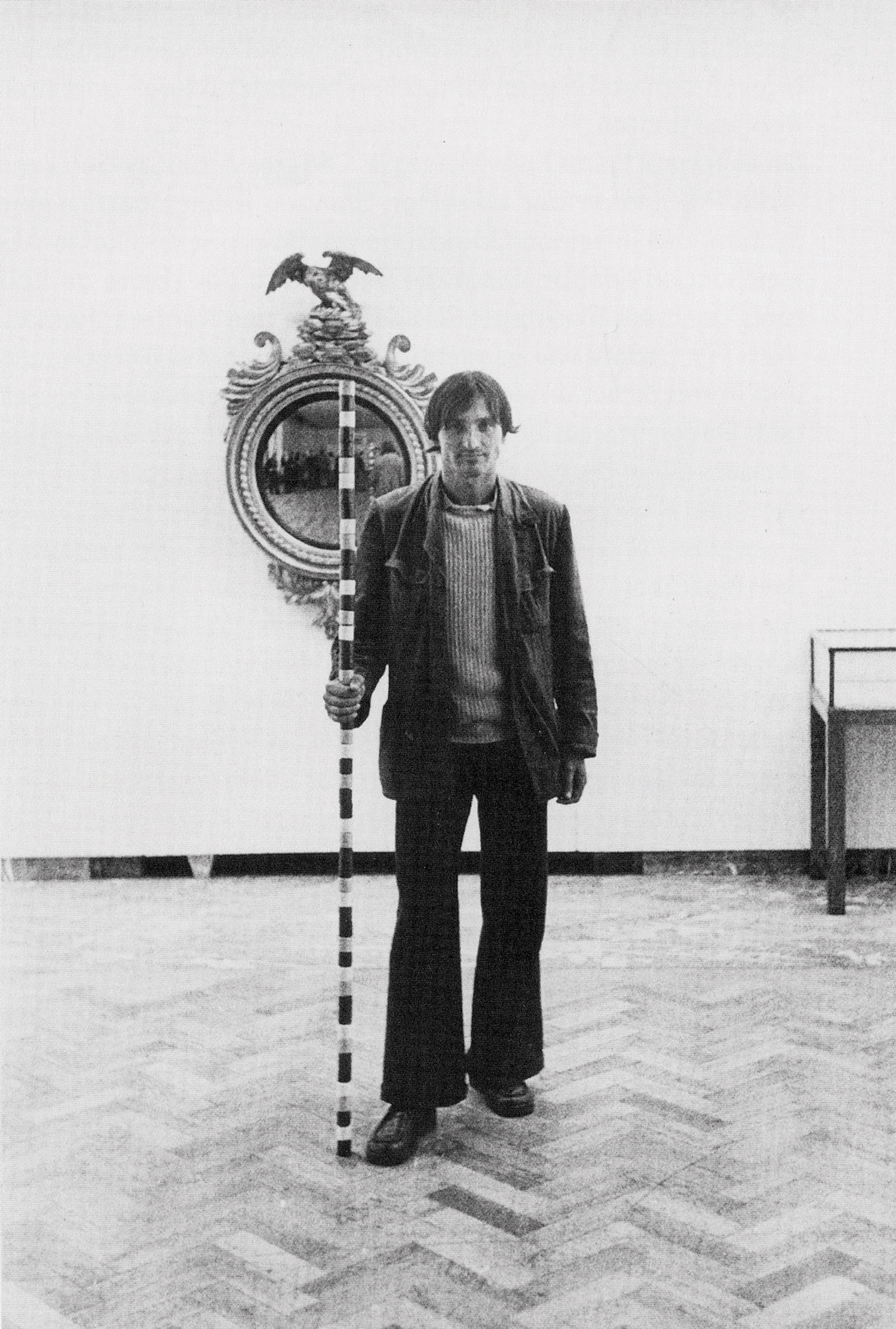

To return to this idea of roots, I should mention a few other people who we are working with that will anchor “Making Worlds” historically, so to speak. I don’t know exactly how to define these artists, but some people would define them as artist’s artists; they are well known but particular sources of inspiration for younger generations. We have André Cadere, a conceptual artist from Romania, and we have a piece by öyvind Fahlström, the Swedish political pop artist. We have a piece by Gordon Matta-Clark. We have a piece by Blinky Palermo, Lygia Pape. We have the instructions by Yoko Ono. And this is of course where it could have been perfect to have Bruce Nauman — but I’m so happy that this happens in any case! Especially in a more substantial way than we could pull off. I want to ask you: on one level some could say it’s important to present new things in Venice; on the other hand it’s important to show things that give a lot of inspiration to the art world, several generations, and there’s no doubt that Bruce Nauman is one of the most important.

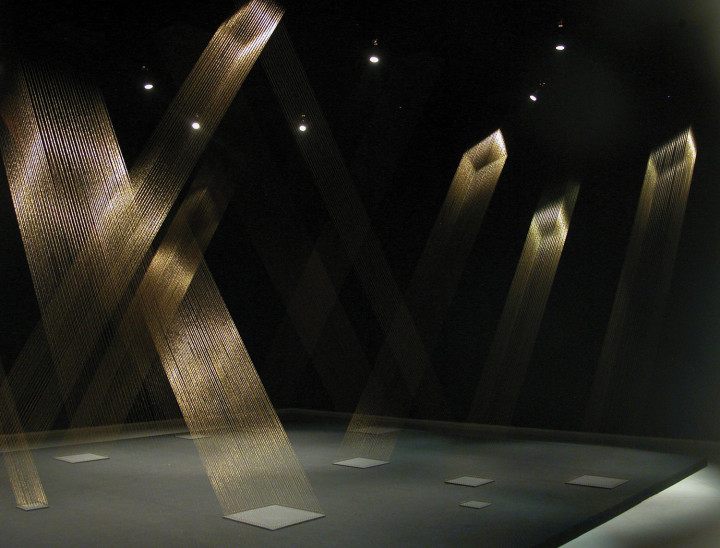

CB: First, I want to pick up on the possible relationship between the main exhibition and the pavilions. Historically, the pavilions came out of the main exhibition. Of late, they have grown independently. In 1993 Achille Bonito Oliva made this wonderful gesture of asking pavilions to invite artists who were not nationals to really rethink the notion of national identity and to reconnect the pavilions with the exhibition. I feel that in a much more spontaneous way that seems to be happening with this edition — for example, there is an attempt at rethinking the way in which the Giardini works by reestablishing the presence of the Biennale’s archive (ASAC), which was founded in the ’70s and conceived to be at the very heart of the institution. That ideal was partially forgotten. This year’s U.S. Pavilion with Bruce is trying to articulate the fact that the United States can hardly be considered as one territory that coincides with one people that coincides with one culture — which is the presupposition that historically enabled the creation of the pavilions. In Nauman’s work, it is more like a field of heterogeneous forces that are constantly interacting and producing very different forms of equilibrium. It was the choice of Nauman that prompted us to rethink the Pavilion and its relationship to the city.

DB: I often get the question from journalists, as if I have to defend the structure of the Biennale. Of course on one level it’s easy to make fun of the Biennale as if it’s some sort of Olympic Games of art from the 19th century. But if you use this nation state structure as a starting point to discuss issues of identity and nationality it’s actually very productive. The Liam Gillick project will be a success if people ask how can it be that there is a British artist in the German Pavilion.

The thing for me about Nauman and trying to define these key artists who are kind of ‘batteries’ for our days — that’s why I involved people like Blinky Palermo or Gordon Matta-Clark — is that I get the sense that he helps us to get even further back. In thinking about his work we are also catapulted back to Samuel Beckett. Early Nauman work is a kind of repetition of the original avant-garde in a productive way. So it’s these kind of artists that help us ride histories and help us understand where we are now I think. Obviously we’re not writing art history books when we curate shows, but it’s interesting if the shows can help us understand where we are now — so it’s more genealogy than history I guess. It’s like historical lines written from our now, and that’s where one can begin to introduce artists that have been forgotten but nonetheless help us understand who we are. Someone like Cadere, or even more so öyvind Fahlström, are examples.

CB: Do you think it is the context of Venice that made you think more about historical figures or was that something that you wanted to do in any case?

DB: Well, of course we are going to introduce lots of young artists. But, for example, we also want Gino De Dominicis in there — it might just be one painting. There are several Italian painters, or artists, in the exhibition who cannot be fully understood without De Dominicis; we will have Pietro Roccasalva in there, Alessandro Pessoli and younger Italian artists — they need De Dominicis as a backdrop.

MP: Are there any more examples that you would pick out in terms of these lineages?

DB: One line for me is that there’s something interesting in the painting in the extended field discussion that still continues. There are so many artists that are being painterly without being ‘oil on canvas.’ We have works by Tony Conrad, a new monochromatic work by Cildo Meireles, Michelangelo Pistoletto with mirrors. But I would say even younger artists like Wolfgang Tillmans or Ulla von Brandenburg, they’re not painters in any kind of classical sense, but Wolfgang has always had this closeness to moments of abstraction, even if the pictures seem to be about social gatherings and alternative ways of living together. Ulla von Brandenburg does these big kind of constructivist architectures within which films are screened, but there’s also a proximity to the tradition of abstraction. I want the painterly world to be in there without it becoming a reactionary idea about returning to painting.

MP: Daniel, you’ve mentioned your aim to present certain works that can slide with relevance into periods other than their own. You’ve mentioned the archive, but are there any other ways you are thinking of to tease out this concept of ‘riding histories’?

DB: In the end it’s an exhibition and one cannot turn it into an educational structure or performance base. But we are presenting some work that will be produced on site, such as Yona Freedman’s. There will also be a few time-based elements and a big poetry ingredient in the exhibition; we have a thing called the Moscow Poetry Club — it’s a Russian initiative but it will involve 50 international poets who will do readings inside the exhibition. We’re also working with Arto Lindsay, the music producer, and we’re doing a big parade — it’s going to happen once and then it’s gone. So that’s something which is far away from the classical exhibition in the museological sense. I’m interested in previous models; I collect art books and the catalogues from the ’60s Moderna Museet shows, exhibitions such as “Poetry must be made by all” and other such visionary endeavors that Pontus Hultén did are models that inspire me — they’re about a different kind of display, a different way of presenting art that involves production, performativity and interactivity that still, when you look at those catalogues, feel very forward looking.

CB: I understand there will be a show of Futurism at the Museo Correr and this is interesting because Futurism has a very disputed legacy, but one of the interesting aspects of Futurism is that it inaugurated a modern exploration of interdisciplinarity. This happy coincidence might be one of the felicitous ways in which the Biennale will make us rethink some of the still-productive aspects of historical Futurism.

DB: Also there will be a few things from the archive of the Biennale that we will show in the Biennale. Futurism was not necessarily only politically progressive, but there’s something with the idea of a non-nostalgic that I like a lot. I hope that “Making Worlds” brings back expressions from a recent past not for nostalgic reasons but in order to find the tools to make possible new beginnings. Baratta has opened up an entirely new area. At the very end of the Arsenale there’s now a garden that has never been used before — the Giardino delle Vergini. It’s not such a classical place for contemporary art but we have involved lots of artists to do interventions and react to this fairytale-style garden. We have works there by a young Thai artist called Att Poomtangon who has hardly been seen before, Sara Ramo, Miranda July, Tamara Grcic from Germany, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Lara Favaretto, Nikhil Chopra, William Forsythe the choreographer — I’m not sure if it’s a futuristic garden but it’ll be interesting to see what this new venue throws up. We have tried to create a varied exhibition that has different zones of articulation within one big show.

MP: You have both been involved in the Biennale before — how much do you feel the Biennale’s legacy impacts your curatorial decisions?

CB: It’s a pertinent consideration because the history of the Biennale is still not that well known. However, in the case of the U.S. Pavilion its history is pretty well recorded — there’s one excellent book on the history of the U.S. Pavilion by Philip Rylands, the Director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. You can truly learn almost everything there is to know about that building and its shows. One the other hand, the preparation for the shows at the Pavilion starts quite early, comparatively speaking, so you almost have the minimum amount of time that you need to precisely organize an exhibition. In the case of the main exhibition the situation is quite different because its history is relatively unrecorded and the timing is extremely short.

DB: It’s not like an American museum show where you can spend three years doing research and make the list. But I don’t think it would actually help so much to have more time because it’s the same group that do the architecture biennale, it’s the same group involved with theater, dance, music and even the film festival. So actually, by the time they have time for you there’s only half a year left and that’s the way that this biennale works.

CB: Did you come to the Biennale with a clear idea of what you would like to do?

DB: Getting the phone call asking you to do the Venice Biennale is not something you plan for, but at least since I’ve been involved — the same year as you were — one knows what it is, you know what you cannot do. Probably a person who isn’t doing exhibitions all the time would have a very different reaction to the invite. I think an exhibition on this scale is only possible if you’re in the middle of things.

CB: This differentiates the Biennale in Venice from Documenta in Kassel. For Kassel, you’re almost asked to reinvent the wheel. And in Venice you just have to set it turning to a certain degree.

DB: Absolutely, and you’re probably already part of the machine turning that wheel, otherwise you wouldn’t be a relevant candidate. Kassel is different. I would say that Kassel could be done by someone who is not a curator. Imagine they would have asked Michel Foucault to curate Kassel — obviously a fanciful suggestion — but my point is that someone who has a radically different take on things could theoretically stand four years to research and make that exhibition. Venice is different.

CB: In this way Venice becomes a curator’s tour de force. It is an exhibition that can only be done by someone who has a certain training — and even for that person it’s an amazing effort!

DB: It’s the ultimate challenge. I can tell you now!