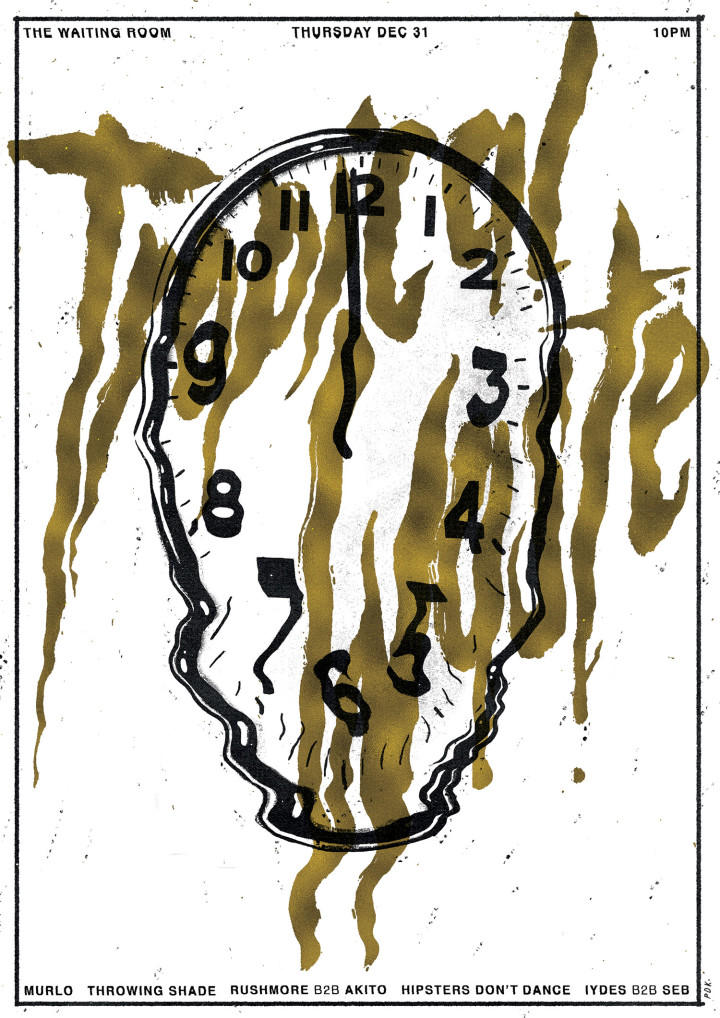

Down a flight of stairs, beneath an unremarkable, noisy pub in Stoke Newington, North London, lies a basement club called The Waiting Room. Once known as The Drop, evoking its steep steps and tight squeeze, it is the home of Tropical Waste, a bimonthly clubbing event held for the past two and a half years in this intimate, 120-person-capacity space, that is without a stage and lit solely by a dimmed red lamp. Organized by journalist Seb Wheeler and music producer Joe “Iydes” Brooks, the events have become a nexus for new and experimental electronic music, pulling in exciting global talent.

Down a flight of stairs, beneath an unremarkable, noisy pub in Stoke Newington, North London, lies a basement club called The Waiting Room. Once known as The Drop, evoking its steep steps and tight squeeze, it is the home of Tropical Waste, a bimonthly clubbing event held for the past two and a half years in this intimate, 120-person-capacity space, that is without a stage and lit solely by a dimmed red lamp. Organized by journalist Seb Wheeler and music producer Joe “Iydes” Brooks, the events have become a nexus for new and experimental electronic music, pulling in exciting global talent.

Artists such as Melbourne-based New Zealander Air Max ’97, Barcelona-based Austrian Zora Jones, Berlin-based American Lotic, as well as Swedish Dinamarca have all had their UK debut here. Eighteen-year-old Staycore crew member Toxe, as well as Kablam and M.E.S.H., have also performed here, along with a line of gifted native Londoners and transplants: Endgame, Felicita, Gaika, Kamixlo, Rushmore, and Throwing Shade, to name just a few. London-based Macedonian MBJ Wetware and Berlin-based Australian Mind:Body:Fitness have also presented live audio-visual sets, as has local producer and visual artist Hannah Sawtell. Needless to say, the Tropical Waste program is impeccably curated.

As is often the case with the international network of hyper-connected millennials, a major feature of Tropical Waste is its focus on art, not only on its own visual aesthetic, provided by artworks by Bristol-based Patch Keyes, but also that of its featured producers. These are artists, diverse and drawn from all edges of the most interesting parts of the world’s club-music scene, who share a commitment to visual media and collaborations in art. You can see it in Air Max ’97’s single-shot sneaker-fetish video set to the clammy, insistent heartbeat of “Swelter.” It is also vividly realized in Zora Jones’s 3-D-rendered liquid figures and interactive 360-degree video experiments. They accompany her wavy suites of fractured and pitch-shifting vocal samples in Fractal Fantasy, an online collaboration with Sinjin Hawke.

“A lot of electronic music these days is certainly informed by contemporary art,” says Mind:Body:Fitness about the confluence of art discourse, politics and cultural theory in these respective scenes. “In terms of dance and electronic music created within an art framework, it has to pass two gates: not only does the music have to hold up, but also the concepts pinned to the music and how well they interact.” MBJ Wetware and Mind:Body:Fitness combine a shared interest in yoga and meditation, along with a sensibility for doom-laden, frenetic visions (and sounds) of the future, in a fully organic, collaborative, live A/V set, which they’ve also performed at Tropical Waste. Strobes and video respond to Hannah Sawtell’s brutal presentations of shrieking modulators and shifting frequencies presented via speakers, lights and screens she designed herself. All of these artists have a very strong, singular style that they may or may not integrate into their performances; they’re are all very different, yet somehow they all seem to fit.

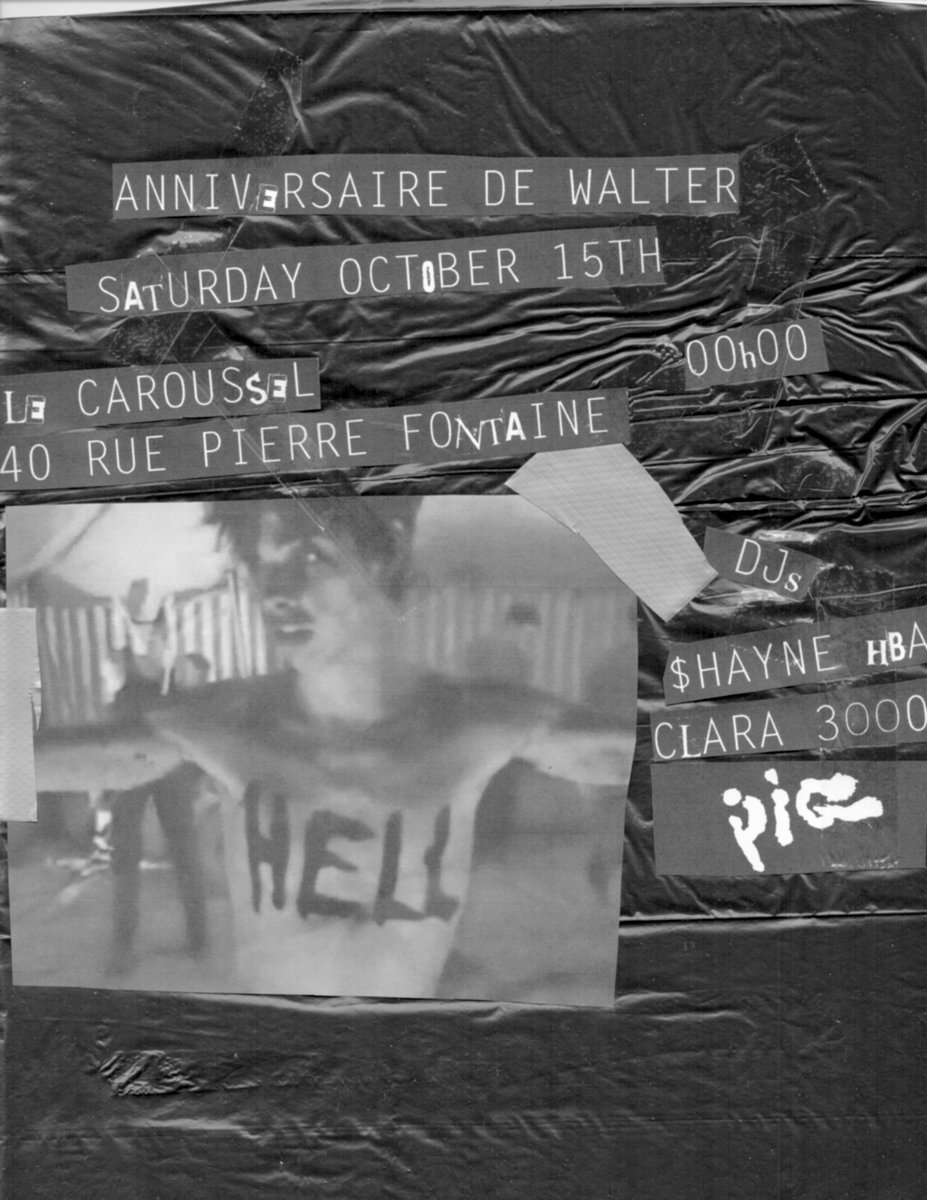

“It’s everything. It’s another language. The counterpoint to the music. I can’t explain my music but visuals can,” offers London-based Endgame about the role of images in his music. He’s worked with the likes of digital artist Kyselina (aka Alberto Troia, who has also collaborated with Lotic), and artist and graphic designer Daniel Swan: his penchant for sexy-though-horror-fueled near-futures found its way onto the cover of Endgame’s first self-titled EP. Swan, along with Endgame, also has a history of working with and wearing progressive London fashion designers such as Cottweiler, while Kamixlo is often associated with Nasir Mazhar. Both Endgame and Kamixlo’s fledgling club night collective called Bala Club, founded along with Uli K, has also collaborated on Nazifa Begum’s menswear collection called Oummra.

“I remember the first one I went to was in an art studio in Bermondsey,” says Wheeler about Endless, a vital South London party, which Bala Club also branched off from. It counts Endgame, Kamixlo and Blaze Kidd, as well as Nkisi, Shanti (aka Yves Tumor) and Uli K as associates, and produced a number of artists that Tropical Waste has enlisted into their own London lineups. “Each artist was just playing on a laptop with their backs to the audience. The laptop was on a really small table and they were just kneeling down playing off DJ software. Their sound system was constantly peaking in the red. It was just raw and had that whole blend of genres, but everything made sense.” Some of these very artists have inevitably found themselves featured in an Unsound Festival program, a week-long Polish arts and music festival that has set a standard for contemporary music programming and been a major influence on Tropical Waste’s eclectic and far-reaching booking policy.

“It’s my favourite festival, and also I think it is just the most important for this kind of music. And it’s really set a template for how you can curate it,” says Wheeler, who credits visits to his grandmother in Krakow during the Polish festival as a core inspiration for Tropical Waste. “Any year you can go and on the same day or night you can see noise and drone, or footwork, techno and everything in between. And it’s all from the experimental side, which is cool. I thought that would be great to do in a club night.”

Unsound’s artists often originate in Western cultural centers: New York, Chicago, Berlin and London, which means its eclectic yet entirely coherent curatorial remit in turn influences a small London-based party like Tropical Waste: “We make a point of bringing different crews together, because there are so many club nights [in London], where you go and just see one clique, one set of people performing together. Whereas we have someone from the red corner, someone from the blue corner, come together, in kind of the same way that Unsound does it. I think we’re incubating a certain attitude to electronic music.”

Asked to attribute a reason why Tropical Waste is unique, a number of the aforementioned artists reference the freedom it offers, as well as its intimacy as a space, and its fearless booking policy. “It feels unpretentious and down to earth,” offers Air Max ’97 via email, while Wheeler himself states: “We like to make sure that the artists we’re booking are from as diverse a range of backgrounds as possible because as promoters we feel like that’s our responsibility, and I don’t think that many other promoters feel that responsibility. We definitely know that we’re two straight white guys who are putting on this party, and that’s quite a privileged position to be in, so we want to make sure that we’re bringing as many people on as possible.”

“It’s quite interesting when nonlocals will come in and start their own thing,” continues Wheeler. “I guess that’s what London is all about. It’s what the city’s built on.” He identifies the one thing about London, as a global cultural and economic center, that makes its creative undercurrents so exciting. “Never mind Brexit,” says MBJ Wetware, a performer and fan of the club night who agrees that it’s the globalism of the London scene — and not a recent political push to isolationism and anti-immigration policy — that parallels the outlook of Tropical Waste and makes it so progressive. “Coming from a country that has been the opposite in terms of sterility and exposure, I have found London so inspiring that I never wanted to leave.”

While speaking with Wheeler, it occurs to me that we are sitting in an organic supermarket café, Harvest E8, in East London, less than a mile down the road from The Waiting Room. It’s one of many indicators of gentrification of a still predominantly working-class and immigrant community that for a time was also an important underground art and music hub. “I heard Dance Tunnel is going to be turned into a cocktail bar, like a speakeasy,” says Wheeler, ruing yet another club closure, a phenomenon which has already claimed Shapes in Hackney Wick, Plastic People in Shoreditch, and most recently Fabric in Islington. “Obviously it would be better if those clubs didn’t close down, but there’s still room to work in,” Wheeler offers. It’s a positive sentiment echoed by producer Endgame: “It’s more difficult in a lot of ways, there are less empty spaces to use, and its more expensive, but there is always opportunity. I’m an optimist: ‘Fuck the past, kiss the future.’”