Darkness hung in the trees, forming a thick mass together with the humid air, enveloping everything. The only features discernible to the eye were those areas touched by the beams of flashlights we wore on bands tied around our heads. We could choose from three different intensities of light, among them a red hue that was less intrusive to the eyes of nocturnal insects. As we staggered through the rainforest, shuffling around on earthen ground covered in evening dew, our guide, entomologist Tracie Stice, pointed out one tiny (or not-so-tiny) body after another, finding her way through the night with impressive agility.

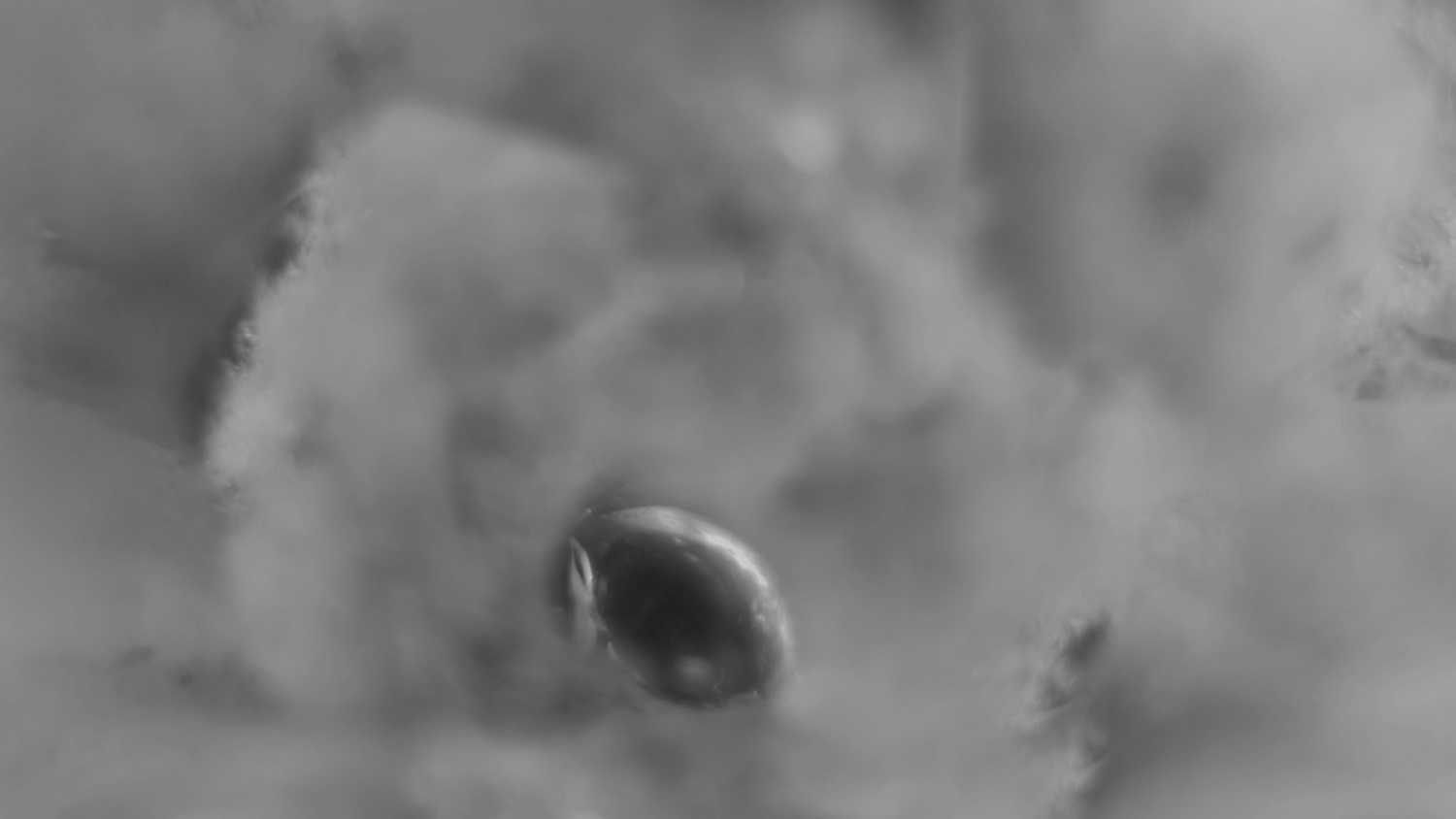

Tracie called us over to where she was poking around the soil with a stick. She found what she was looking for, and with a quick and decisive movement pushed her instrument into the dirt to pry open a perfectly round hatch. Behind it emerged the chunky black eyes of a Ctenizidae trapdoor spider, peering out of its home. While we were still staring at this skilled hunter, thinking about how its presence usually eludes human perception, our guide pointed out a Cyrtophora citricola tropical tent spider clinging to its web. She told her incredulous audience that she had lived with one hundred of these arachnoids in her house. Having dedicated her entire life to these other life forms, she was truly entangled in their being.

It was around this time last year that I encountered these and other spiders in the Costa Rican night. Simultaneously, I was preparing the exhibition “More-than-humans” with works by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Tomás Saraceno from the TBA21 Collection at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. Gonzalez-Foerster’s OPERA QM.15 (2016) — a holographic projection of the artist lip-syncing one of soprano Maria Callas’s most beloved arias — was shown next to a group of works from Saraceno’s long-term spider research. The pairing of the works could be considered unusual — opera being one of the most complex forms of Western human culture, and spiders often being considered as part of the natural world, not makers of culture. Nonetheless, spiderwebs — and doors — are complex architectural creations; some arachnoids weave them anew every night, only to devour and re-digest them the next morning while waiting for dusk to fall over their hunting ground. Other spiders build lassos from their silk, which they shoot with precision to catch their prey. Their use of tools is both versatile and remarkable. In human terms, we might refer to these inventions as culture. As for opera, spiders do not have an auditory apparatus, but they can nonetheless discern the vibrations of an approaching insect or human. In 2016, researchers discovered that jumping spiders, Phidippus audax, can detect human speech through quivers of the hairs on their legs. Spiders and their webs are nature-cultures.

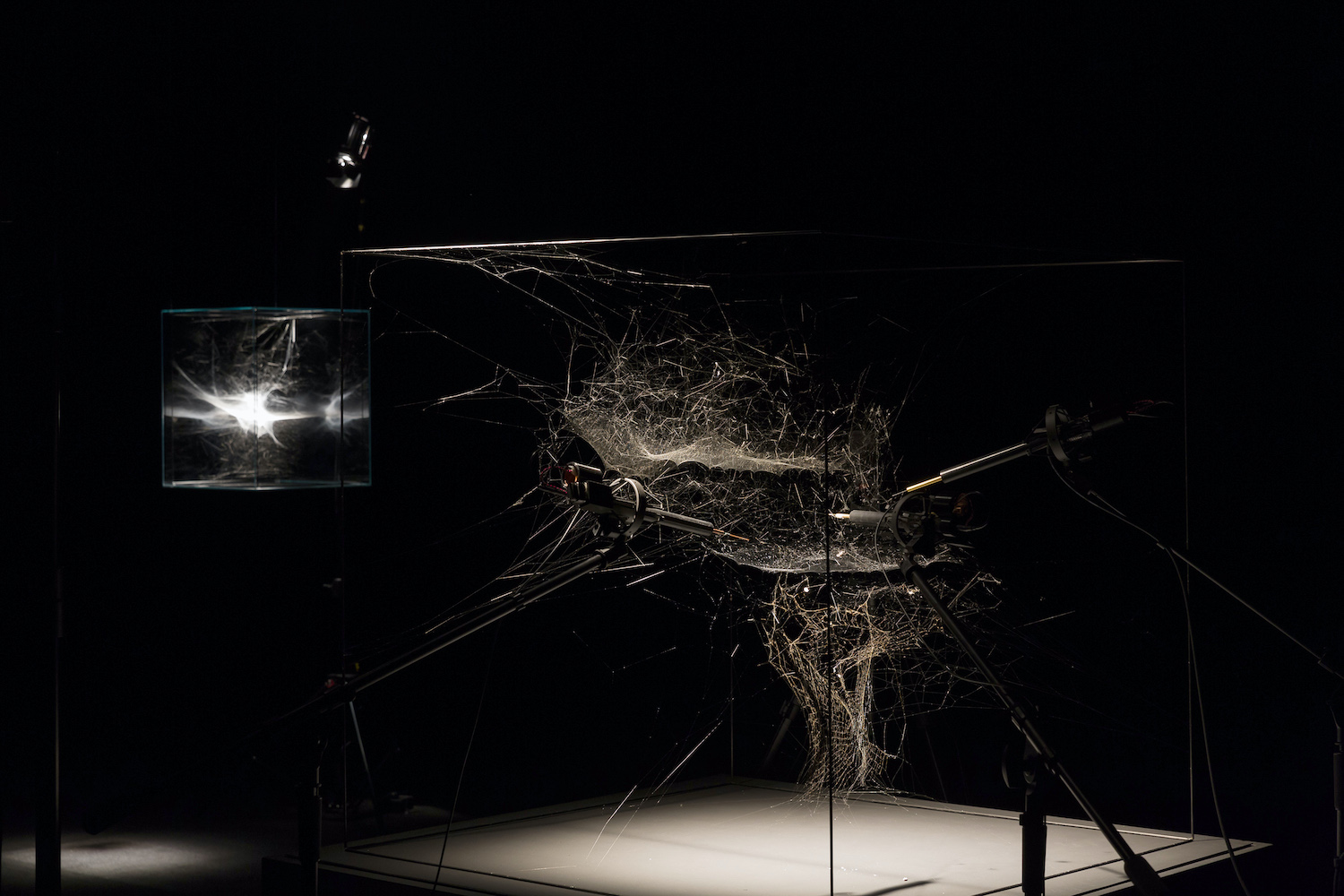

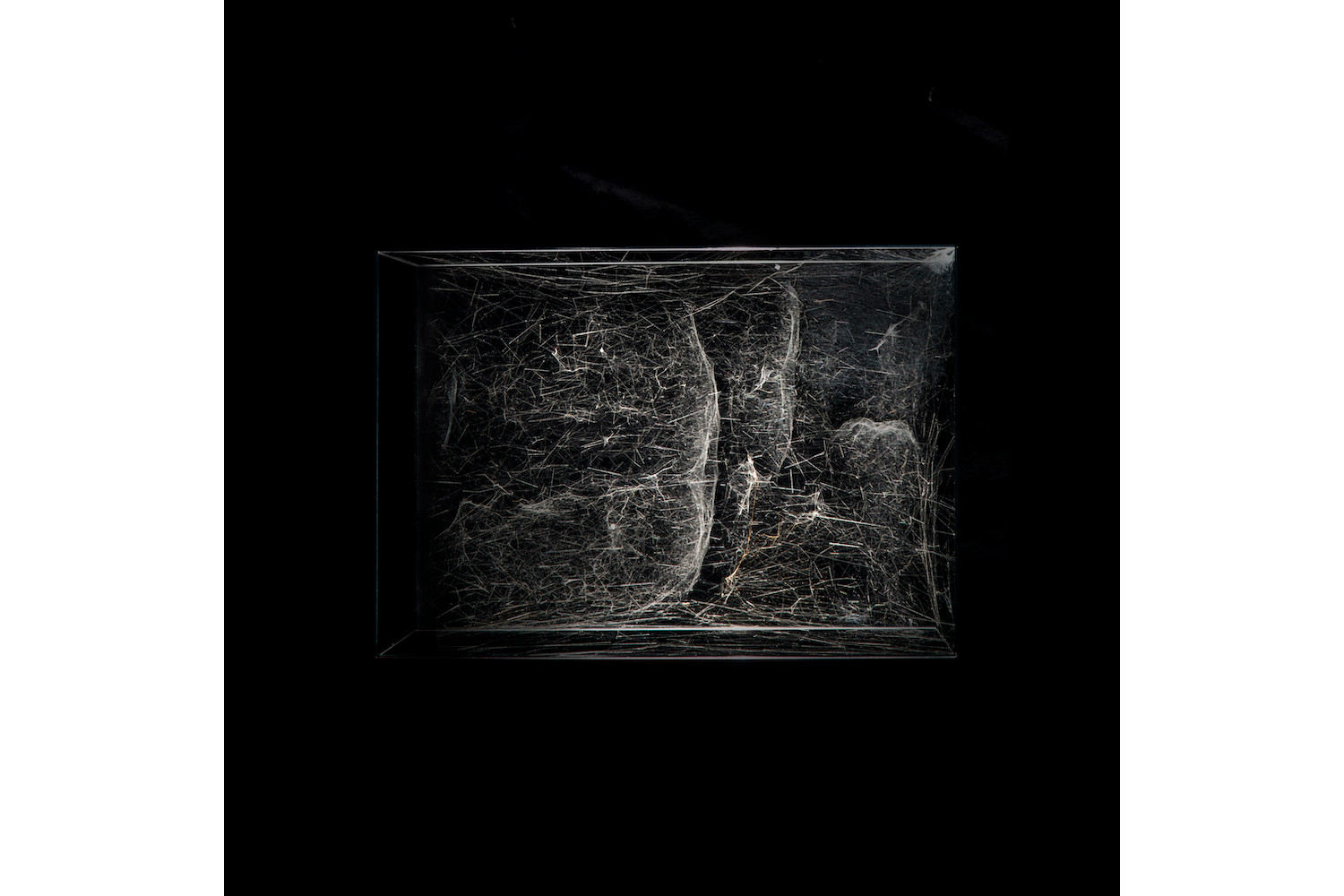

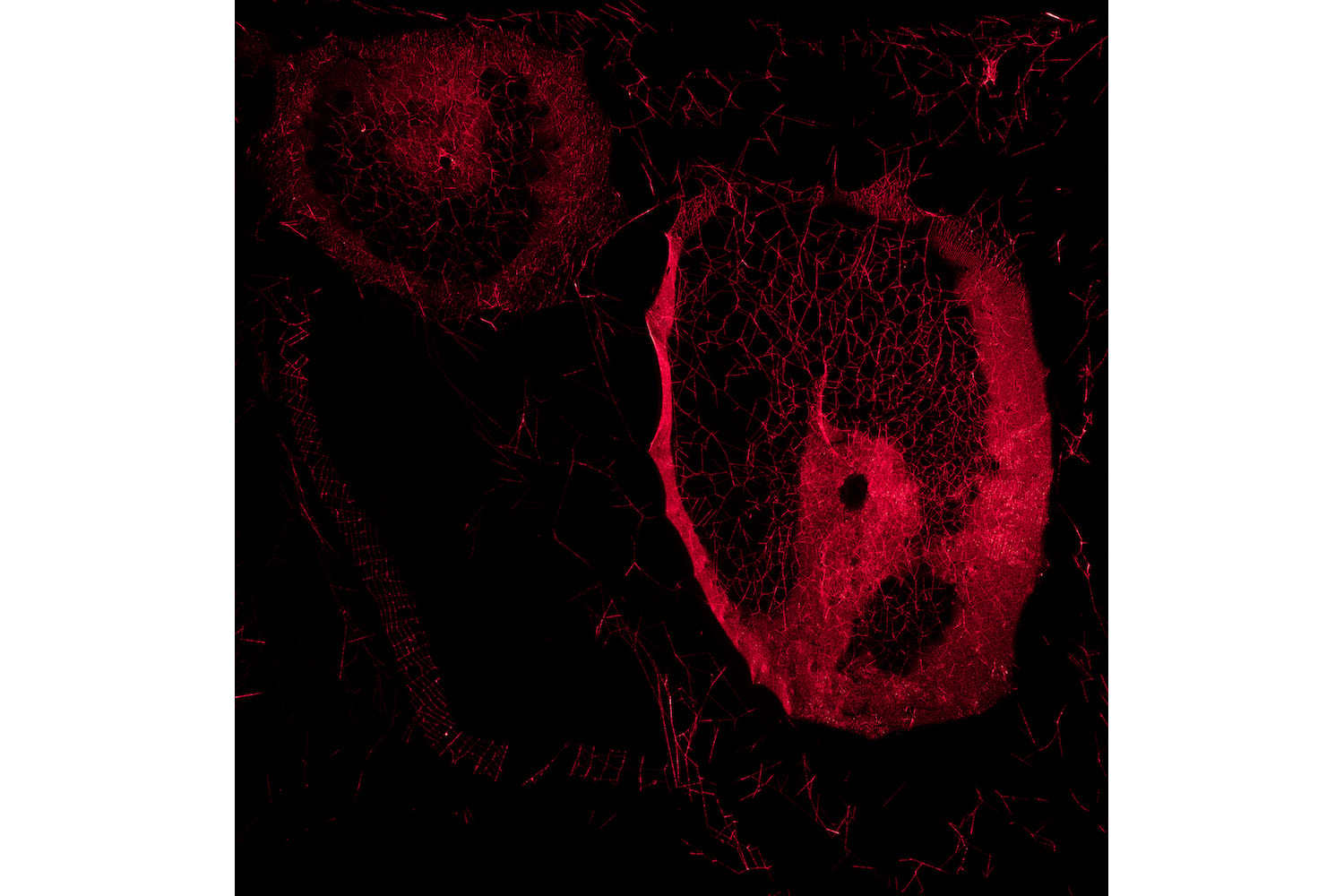

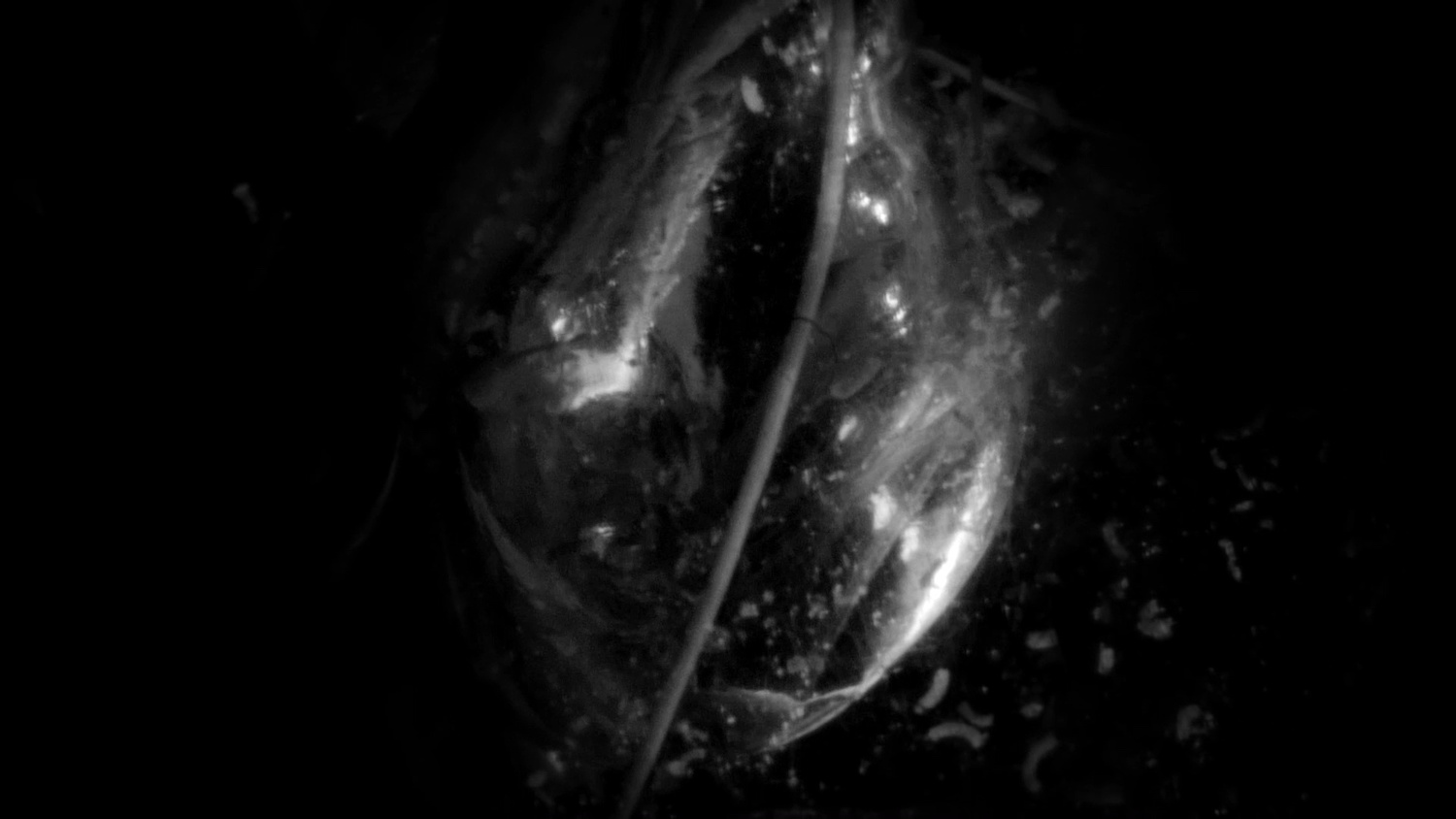

Saraceno’s practice is situated at an equivalent interstice between living bodies — both human and nonhuman — and entangled in their ecological surroundings. In his installation Hybrid semi-social solitary Instrument HD 74874 built by a triplet of Cyrtophora citricola — four weeks and a solo Agelena labyrinthica — one week (2019), for instance, three tropical tent-web spiders and a single funnel-web spider engaged over four weeks and one week respectively to build a complex web using their combined skills. Spiders of different species usually don’t weave webs together. Nonetheless, biologist and expert in vibrational communication Roland Mühlethaler and other researchers collaborate with spiders in Saraceno’s studio to create new hybrid architectures. In the installations, consisting of composite webs encased in glass boxes and suspended from the ceiling, the different weaving techniques and hues of silk can easily be discerned, in this case forming sections of golden and silvery-white threads. To build these conglomerates, the spiders each weave in their species-typical manner while also creating what one could call improvisational connections with the other webs. Nodes and attachments produce relations that are representative of multiscalar connections between diverse species that may at first sight appear unrelated. In these novel formations, the spiders act as role models of interconnectedness, in which attempts at matching sameness are surrendered in favor of embracing difference.

Evolutionary theorist and biologist Lynn Margulis propagated the term symbiogenesis to describe relations between organisms and their environment, including other organisms, as a form of open-ended mutual becoming. In her view, the symbiosis of organisms affecting one another — in fact co-constituting one another — is a more apt understanding of the natural world than the disproportionate focus on competition in classical Darwinian evolutionary theory. To better accommodate these entanglements and their novel recognition by Western humans, Saraceno’s studio is developing a glossary of terms to communicate about their work. Rather than speaking of spiderwebs, for instance, they refer to these living-non-living undividable composites as spider/webs.

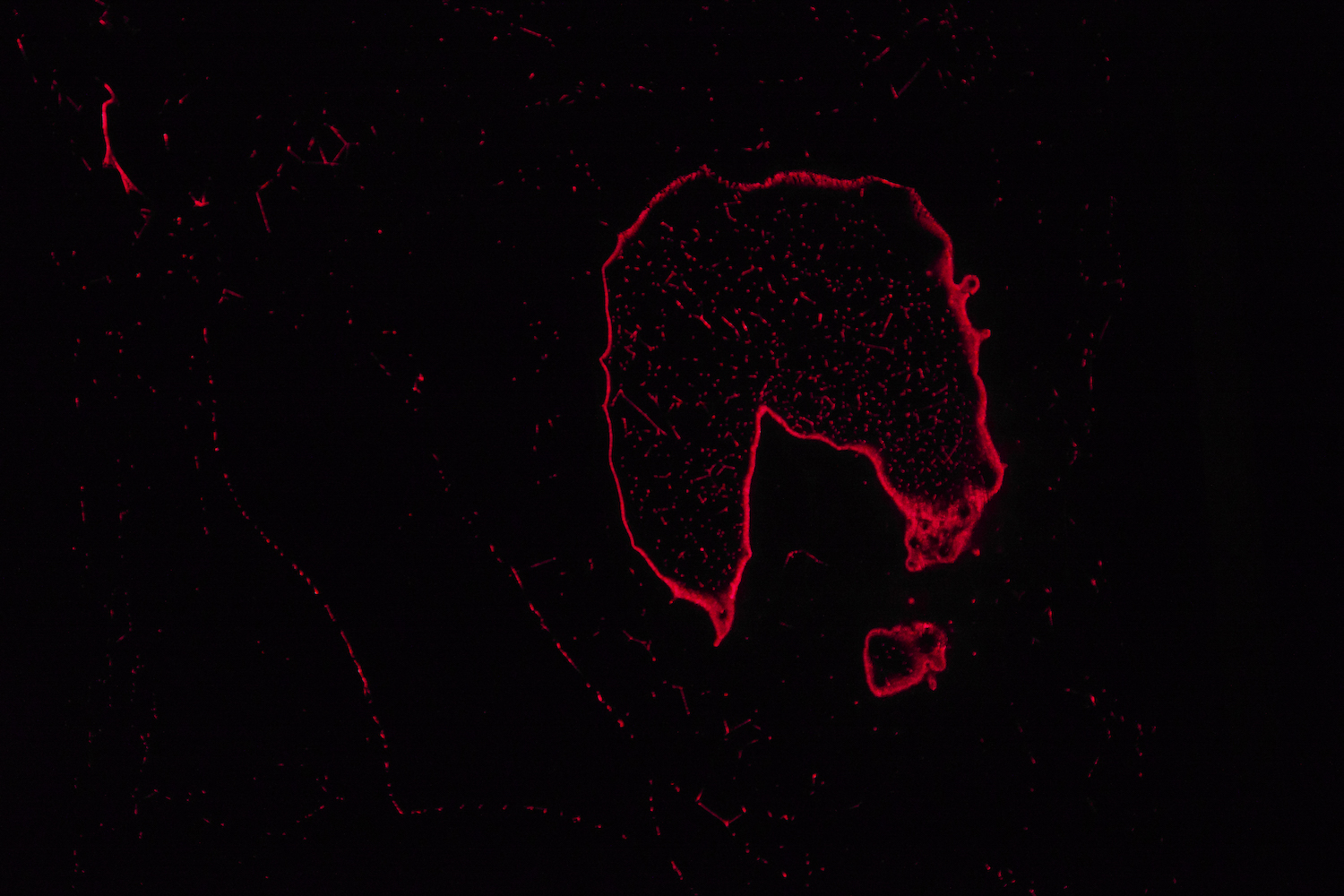

In another of Saraceno’s installations, How to entangle the universe in a spider web? (2018), a spiderweb is installed behind a glass sheet installed flush inside a wall. A red laser positioned out of view at one side moves slowly back and forth to illuminate different cross sections of the three-dimensional structure. The work seems like a film installation, or an animation of the urban layout of a busy metropolis. The wandering laser sheet reveals the intricate arachnoid architectures, which often remain hidden to the human eye, while composing a moving image that does not represent the web but visually amplifies the structure itself. This gesture to me reads as one of respect toward the expressive possibilities of other species, which do not ask for human representation yet deserve acknowledgement of their worthy existence, however foreign it is to us. In Saraceno’s activation of spiderwebs in musical performances, such as the Arachnid Orchestra. Jam Sessions (2015), performed at the NTU CCA Singapore, he similarly, in this case sonically, amplifies the silk’s vibrations to make it audible to human audiences. In doing so he highlights that which exists regardless of human intentionality by homing his anthropoid listeners in to their auditory and otherwise shared spaces with other species.

Saraceno’s studio, perhaps a bit like Tracie’s home, is an ecosystem of nonhuman and human collaborators who are experts in different fields including arachnology, music, and geography. Titled Spider/Web Department, the research collective focuses on multispecies ecologies by taking cues from anthropologist Anna Tsing, who calls for the need to cultivate different “arts of noticing.” The conversation about interdisciplinarity in art is continuing to gain traction, and yet it often stops short of being truly transdisciplinary to the point that boundaries dissolve and something novel emerges. In Saraceno’s case, to the contrary, the cross-disciplinary conversations and applied experiments create reverberations that leave no participant in the ecosystem — or web of relations — untouched. These dialogues, it seems to me, provide one of the most fruitful grounds for inciting new — and rediscovering old — forms of thinking and feeling in relation to our environment. They allow different scales, places, and temporalities to matter, regardless of whether they seem immediately crucial to humans or only indirectly so. If we take the interwoven histories, present moments, and possible futures of interspecies ecologies seriously, then we need a plurivocality of disciplines and non-anthropocentric perspectives to engage in common dances founded in the resonances of our shared cosmic web.

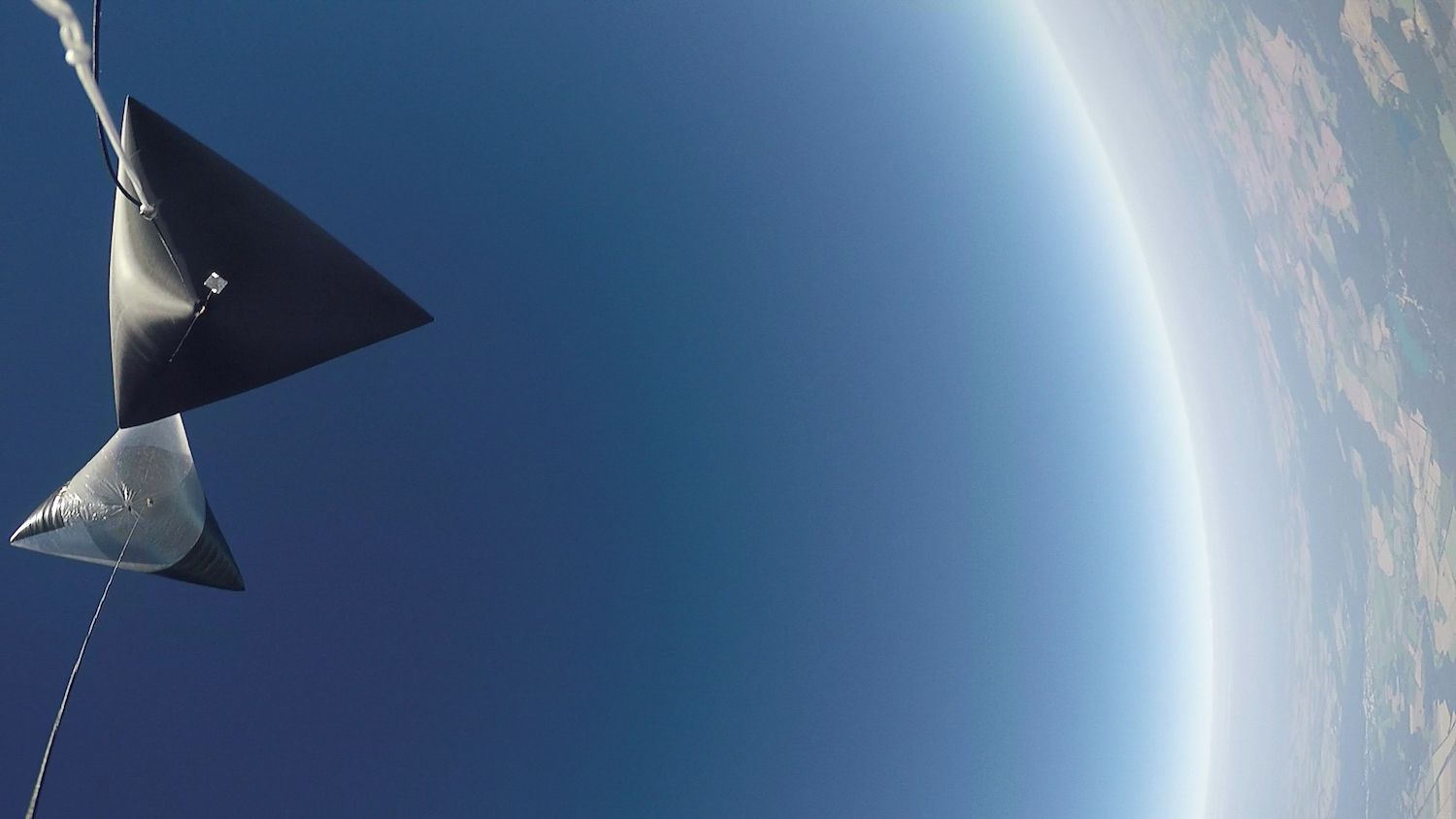

Just as committed to ecological concerns is Saraceno’s perhaps most well-known project, the interdisciplinary artistic community Aerocene. A wordplay on the Anthropocene era and air or flight, this long-term initiative intends to find ways of flying without using any fossil fuels or creating carbon emissions. On January 25, 2020, the Aerocene Pacha hot air balloon, which had been developed and prototyped by the community to harness only the sun and wind, lifted a person into the air, reaching an altitude of 275.5 meters above the Salinas Grandes in Jujuy, Argentina. The vehicle, using lighter-than-air technology, travelled for a distance of 1.73 kilometers over the duration of one hour and fourteen minutes before landing the person safely on the ground again. Aerocene is an attempt at alleviating environmental degradation through air travel while also critiquing national borders. The project further questions transportation as merely utilitarian, highlighting the joy that accompanies the act of floating in the air. In balloon flight, the traveler can only adjust the speed and direction of travel to a certain degree, and therefore needs to surrender to coincidence and to being carried by forces outside of their control.

In an interview I did with Saraceno’s studio in 2016, the team referred to seventeenth-century philosopher Francis Bacon’s experimenta lucifera, a set of experiments intended to discover simple rules of nature, but which at the outset have no purpose other than to fulfill curiosity. Saraceno proposes taking back experiments from the “high” realm of science, to profane them, in the sense of philosopher Giorgio Agamben, and free them of their imperative to serve specific ends. In this sense, the Aerocene project relies on playful, speculative experimentation, yet it is also integrated within the holistic understanding of ecology in Saraceno’s work. In science fiction writer Liu Cixin’s book The Three-Body Problem, the inability to conduct fundamental scientific research leaves the Earth’s citizens unable to devise an effective defense system against extraterrestrial invasion. Especially in a time plagued by climate change, a global health crisis, and unending social injustice, fundamental scientific research is incredibly important. Nonetheless, it is crucial not to forget that knowledge production, like art, cannot be endlessly instrumentalized if it is to matter, and that other forms of knowledge, be it non-Western epistemologies or nonhuman intelligences, need to be given the space to transform what is considered knowledge. Recognizing our ties with other species and taking them into account in research offers the potential for a new cosmopolitics — to use the words of philosopher Isabelle Stengers — of shared ecology and care toward other species.

Returning to Saraceno’s spider research, his studio’s speculative approach has also made applicable contributions to the scientific field. For instance, the team developed a scanning technique that allowed them to digitize for the first time a three-dimensional web. Due to the intricate architecture and the limited, mostly still bi-dimensionally oriented focus of scanning technologies, this was no small feat and gained the artist recognition within the science community. Finding a productive balance between speculative and applicable science, and art, is needed more than ever today.

Back in the night in Costa Rica, Tracie told her captivated audience about an incident when a monkey broke into her house where she lived with the one hundred tent-web spiders. In Tracie’s story, the monkey ended up eating all of the spiders. In another version of this story, it let them live and stayed to admire their webs.