Nostalgia for 1990s TV, film, web culture, or art should not seduce anyone who lived through it the first time around. Perhaps it’s fine that our childhoods are being sold back to us with added retro value, but we shouldn’t pretend that this reappraisal is anything like how things really were.

With “Time Is Thirsty,” curator Luca Lo Pinto tries to make a “temporal mash up” of the sights, sounds, and smells of the 1990s — specifically 1992, the year Kunsthalle Wien was founded.

The result is overtly eerie. Most of the huge first-floor space is left empty, with dim lighting that changes throughout the day, and a soundtrack in the form of a fifty-song, seven-hour-long underground electronica playlist by musician Peter Rehberg, which plays on shuffle from speakers lined up against the left hand-wall and rigging affixed to the ceiling.

Lo Pinto makes two moves: he politicizes a context depoliticized by what Mark Fisher, following Fredric Jameson, calls the “formal nostalgia” of contemporary culture, with works by Chris Wilder, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Lutz Bacher; which in turn allows the textures of works by Anna-Sophie Berger, Willem de Rooij, and Georgia Sagri to act as a kind of conscience, adding to the atmosphere even if they have no clear political motive.

Wilder’s Press Clippings sets the scene. This selection of newspaper articles on key events in 1992 — raves, the Los Angeles Riots, the advent of women priests, environmental disasters, anti-immigrant violence — directly establishes the exhibition’s social context.

So does “Untitled” (It’s Just a Matter of Time) by Gonzalez-Torres, a billboard that was installed in Hamburg, New York, São Paolo, El Paso, Düsseldorf, and now Vienna, each time conveying the title’s parenthetical admonition via classic gothic font in the official language of the country in which it is displayed. The work related the AIDS crisis to anxieties about the end of the century — anxieties that feel no less timely today.

Because it combines body horror with consumer goods, Bacher’s Untitled (Denim) (1992), an oversized pair of Levi’s jeans stuffed with packing material, offers a link between the political and the visceral. If we recoil at the grotesque idea that a person could, literally, be that huge, we should also worry about how such garments are made.

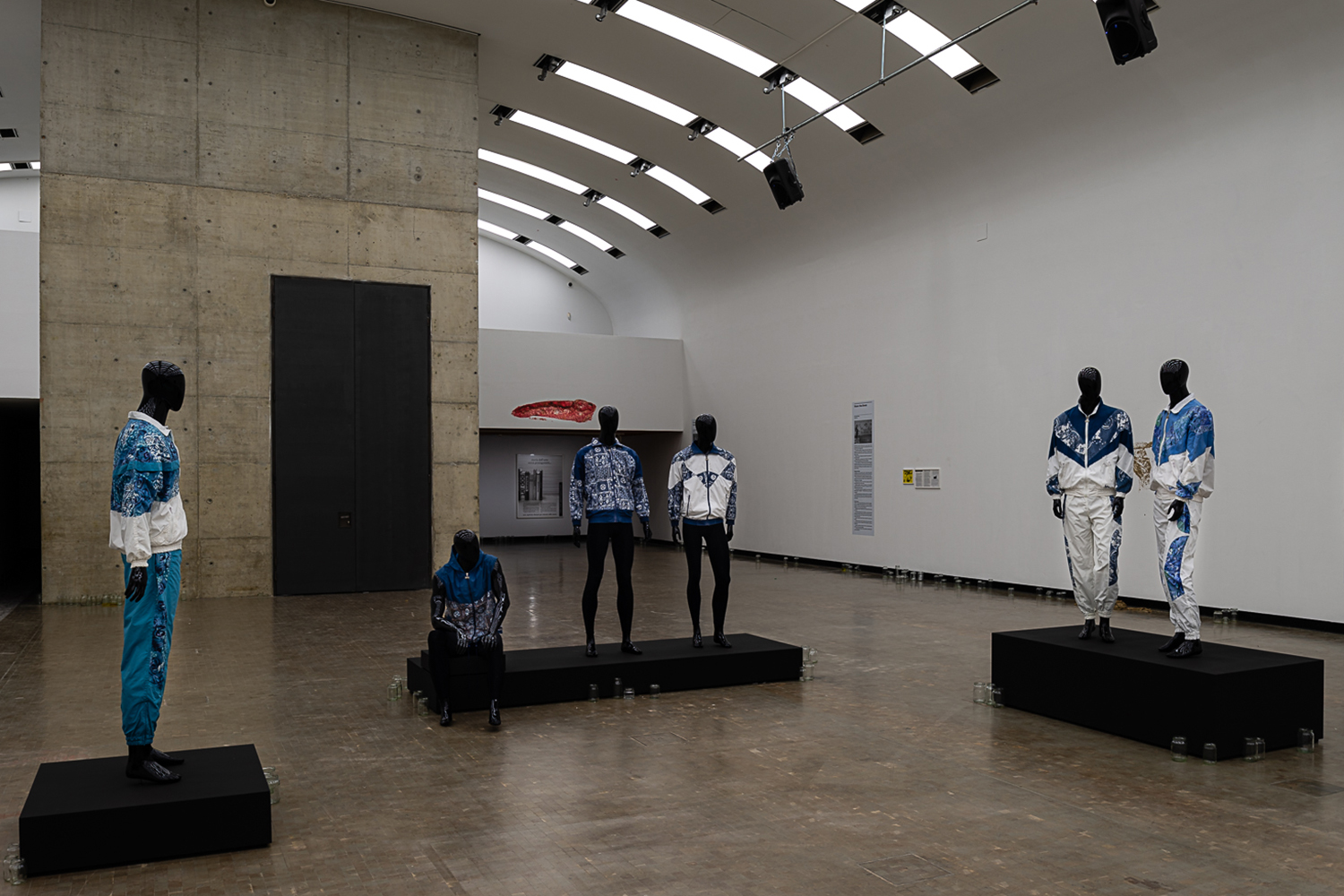

Such concerns are, however, largely absent from De Rooij’s selection of six garish blue-and-white tracksuits (all 2015), modeled by static shiny black mannequins on raised platforms in the middle of the space. We need to remind ourselves that, although they might once more be trendy, these clothes were — and still are — produced by labor outsourced to the developing world, often assembled by teenagers earning $2 a day in firetrap sweatshops.

Nostalgia can’t coexist with such a sense of disgust, which is a little too obvious in Anna-Sophie Berger’s Time that breath cannot corrupt (2019), three mud-splattered polyester lace coats, and Georgia Sagri’s fresh bruise, open wound, and deep cut (all 2018), three laser-printed vinyl stickers of ugly bodily injuries. They might make us balk, but it’s all on the surface, just like everything back in the 1990s.