“The successful negotiation of holes is dependent on maintaining a healthy respect for what cannot be seen.” – Pope. L

Over winter in London, like many, I’ve found myself preoccupied by thoughts of elsewhere. I found solace in Alia Farid’s beautiful Chisenhale Gallery commission “Elsewhere,” curated by my colleague Olivia Aherne, and in conversations that erupted around it. This new body of work focused on transregional solidarity between Puerto Rico and Palestine via sixteen exquisitely woven textiles made in collaboration with weavers in Samawa, Iraq. Each intricate tapestry forms part of a growing material archive initiated by Farid in 2013 that traces how architectural styles, symbols, rituals, and other social devices coalesce across continents and express shared struggles.

Farid and I, with my colleagues Rachel Be-Yun Wang and Oscar Abdulla, developed a series of events alongside the exhibition, inviting others, including scholar Maru Pabón, curator Odessa Warren and artist Joe Namy to reflect on Farid’s work. On February 1, in the show’s final week, Namy hosted a sold-out listening session at the gallery, inviting Nihal El Aasar, Christina Hazboun, and Sasha Shadid to contribute. We spent an evening with forty fellow attendees, listening to and discussing tracks, including the anthem of C.D Palestino, the Chilean football club founded by Chile’s Palestinian community members, soundscapes from Gaza and Bethlehem, and Palestinian wedding songs. It was a night inflected with joy, grief, and deep solidarity.

Elsewhere in the city, brightening January, was “Premiums,” an interim presentation of artists’ work from the Royal Academy’s post-graduate program. The week-long presentation shared new and recent work by Suleman Aqeel Khilji, Bishwadhan Rai, Alex Margo Arden, Rosa Klerkx, and Esther Gamsu. A highlight was the quiet authority of Bishwadhan Rai’s sculptures. A collection of delicate objects permeated boxy constructions: stacks of egg crates topped with fragile, hollowed-out wax eggs and adorned with small, pink artificial flowers.

Condo London (2024) also made its post-pandemic return to London at the start of the year. This month-long, typically annual, event sees galleries across the capital invite international peers into their spaces. The initiative encourages smaller galleries to pool resources and create a more sustainable environment supporting artistic risk-taking and experimentation. Along the Condo route, I dropped into Ginny on Frederick (who moved into a bigger space a stone’s throw from their characterful sandwich shop space at the end of last year.) I chatted with gallerist Freddie Powell, who is hosting LOMEX, New York. We discussed the rapid professionalization required of young galleries in the city and lamented the decline of the “project space.” What new models might enable small, non-profit spaces to thrive in the problematic funding landscape of Tory Britain? I visited one answer to that question in the shape of Terminal Projects the following day. They occupy a huge billboard on the edge of a business park in Greenwich, South London, and a new work by Aurelia Guo had been unveiled the night before. I enjoyed encountering Guo’s words in a new context and on a vastly different scale, having previously read her brilliant book World of Interiors (2021), a collection of essays and text fragments that explore the question and cost of survival.

Also taking part in Condo was Emalin, fresh from celebrating the opening of Clerk’s House, their second space in East London. At their Holywell Lane gallery, they hosted Galerie Neu, Berlin. The photographs of Megan Plunkett accompanied the work of Berlin-based Manfred Pernice. Pernice’s sculptures appeared as though they’d all been pushed from the center of the space, like someone had entered the exhibition and decided to make room for a dance floor. Angelina Volk, co-director, pointed out that Pernice had recently introduced a slight tilt to the provisional-looking, cylindrical columns that recur throughout his practice. At Emalin, each work lightly leans towards the gallery’s edges, perhaps reaching for something beyond the boundary or asserting themselves against an external, unseen threat? Resolute, steadfast forms provoked reflections on how we make our presence known in the political sphere and what constitutes action.

Other highlights from Condo included Christopher Aque and Alexandre Khondji at Sweetwater, Berlin hosted at Maureen Paley’s Studio M, Tolia Astakhishvili at HollyBush Gardens, hosting LC Queisser, Tbilisi and, at Hot Wheels Athens’ new London space, an exhibition by Maria Toumazou and the late Cora Pongracz, co-curated with Maxwell Graham, New York.

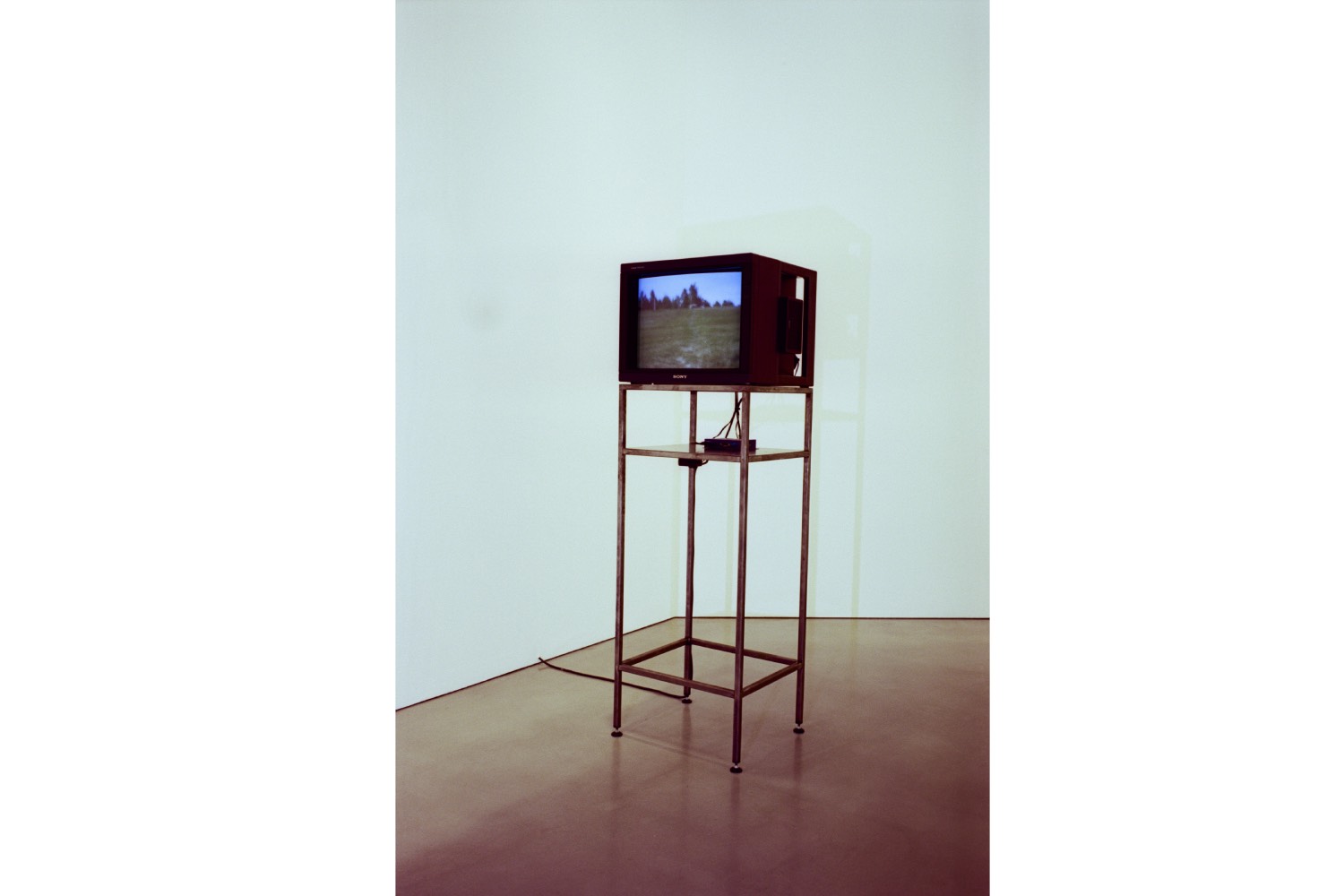

Following Alia Farid’s exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery, there is a major commission and first solo exhibition by London-based artist Joshua Leon. His text-led practice spans exhibition-making, performance, and writing. I’ve been working with Leon for two years, developing an installation that uses forms of annotation to trace collapses of personal memory and recorded history. Through these collapses and an engagement with the history of Chisenhale’s site, previously a veneer factory, Leon excavates a nuanced exploration of Jewish subjectivity, erasure, and withdrawal. Recently, as I often experience when engrossed in a project, the central idea has started to appear everywhere. Collapse was also at the heart of Pope. L’s last exhibition, “Hospital,” which opened at the South London Gallery in November, weeks before his death. In the main space, three large-scale wooden towers fall into one another. The towers are recreations of those the artist constructed for his performance, Eating the Wall Street Journal (2000), in which he sat, covered in flour, on a toilet, eating pages of the journal doused in milk and ketchup. In this retelling, the performer is absent; all that remains are toppling towers and an invitation to imagine what happened or might still unfold. Pope L. has always worked deftly with absence (I’m thankful to Lotus L. Kang for introducing me to his text Hole Theory, which I continually return to), and it feels as though few are better equipped to remind us that possibility and even humor, can persist in the wake of loss, than him. Both Leon and Pope L.’s reflections on collapse offer a space to grapple with the destruction that unfolds from the past and into our present. In doing so, they also gesture towards another form of collapse that invites us to fall into one another so that we might hold each other up.