Two long tunics made by artist Luchita Hurtado hang in my closet. One is ribbed and purple, and the other deep, embroidered red. Both have bell-shaped sleeves and high, button-up necks. Hurtado, who began making both clothes and art as an adolescent, gave them to the late artist Eugenia Butler years ago. Butler’s daughter, my friend, gave them to me.

Having them meant that, though I’d never met her, I already knew one version of her artistry intimately when now ninety-seven-year-old Hurtado had her 2016 solo show at apartment gallery Park View in Los Angeles. Others must have been in the same position — her clothing and her work circulated around New York, Los Angeles, and Latin America from the late 1930s on. There are photos of David Salle sitting with her paintings behind him; her registrar suspects she gave away certain missing works as gifts. At Park View, the layered, geometric fantasies done in crayon, ink, and watercolor between the 1930s and 1950s, and barely seen for decades, were more exciting than surprising.

Ryan Good, director of the Lee Mullican estate, began finding Hurtado’s artworks as he prepared the catalogue raisonné for Mullican, Hurtado’s late husband. Hers were mixed up among his — so far, Good and registrar Cole Root have catalogued 1,100. They showed some to Paul Soto, Park View’s founder. “She had her first show two years ago and sold it out. And now she’s a phenomenon,” said Hurtado’s son, Pictures Generation alum Matt Mullican, in an April interview with Chinese art magazine RanDian.[1]

She did not have her first show two years ago, however. She exhibited occasionally throughout the 1950s, at the Women’s Building in the 1970s, the epicenter of feminist art in Los Angeles, and at Oxnard’s Carnegie Museum in the 1990s. LACMA and MoMA acquired prints she made in the 1970s, though both museums only recently added these to their online databases. It is the curators and gallerists working with her now — Soto, Matthew Marks, Julia Joyce at Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and Anne Ellegood and Erin Christovale, who curated her into the Hammer’s 2018 “Made in L.A.” biennial — who learned of her art within the past two years. Hans Ulrich Obrist, currently working on a thousand-page book of her work, first visited Hurtado’s studio in 2017.

“I live again!” Hurtado said mirthfully during a March interview with Obrist, held in front of a crowd at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. This, of course, was a joke. She has been living and working the whole time, interacting with her artist peers and finding a visual language to fit her experience. “She was always supportive of other women, and certainly of the men in her life (Lee, Matt), never bitter about her own lack of visibility,” wrote Hurtado’s friend, artist Joyce Kozloff, via email. Her work changed dramatically from one period of her life to the next, moving between fast abstractions and studied figuration, during eras when forging a signature, seemingly original style led to art-world prominence. She also mined the personal and the erotic before such interests were widely considered serious. The challenge now is to treat her not as a discovery but as a mature, nuanced artist who, while not an outsider, never worked with the market or posterity as motivation.

Hurtado, born in Caracas in 1920, moved to New York City in 1928. She attended Washington Irving, then an all-girls arts high school, an education choice her mother allowed because Hurtado deceptively promised to become a seamstress. She married Chilean-American journalist Daniel del Solar in 1938, when she was eighteen, through him meeting a contingent of Latin American intellectuals in New York. Among them was the Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo, with whom she would paint in her kitchen. She also met Isamu Noguchi this way, as his sister, dancer Ailes Gilmour, knew the Chilean ambassador and belonged to the circle as well. After del Solar left Hurtado with two young children to care for, she began working as a freelance illustrator for Vogue and Noguchi took her under his wing. He brought her to galleries and introduced her to Viennese painter Wolfgang Paalen. She married Paalen in 1947 and moved with him and her sons to Mexico City. There, she befriended Surrealist Leonora Carrington and met Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Remedios Varo. After her young son Pablo died of polio, the family abruptly moved to San Francisco, where Hurtado became better acquainted with the members of Dynaton, the Surrealist offshoot that Paalen, Gordon Onslow Ford, and Lee Mullican founded in 1949. She married Mullican in 1956, four years after the birth of their first son, Matt. The family traveled frequently, but primarily lived in a rustic home off of Mesa Road in Malibu. Apart from the break she took after Mullican’s 1995 death, Hurtado maintained an almost daily studio practice throughout her adult life. While creature-like abstract figures in her drawings from the 1940s and ’50s clearly reflect a broadly Surrealist sensibility, she shrugs off frequent attempts to align her with either Surrealism or Dynaton. “To say, I’m going to paint a Surrealist painting, no,” she told Paul Karlstrom in a 1995 interview for the Archives of American Art.[2] Since the movement’s early histories rarely included women, there was probably no love lost.

Attempts to read her work as a response to her husband’s also fall flat. Mullican’s work had unmistakable stylistic consistency, hers a more roving quality. In the 1960s, as he made intricate, layered paintings resembling tapestries, Hurtado worked on a series of double-sided oil paintings, hieroglyph-like notations on one side, overlapping bodies on the other, a coming together of her interests in abstraction and the human form. Her mid-1960s series “A Time to Be Alone” consists of charcoal and oil paintings of simplified male, female, and androgynous nudes hovering near and entering each other. Sometimes the bodies are left unpainted, a loose wash encompassing them; other times, they’re a blunt fleshy orange. Nothing is overwrought, in stark contrast to the figuration of her Surrealist friends. The shapes and motions read as confident and precise, an efficient yet still erotically charged study of how bodies relate. They also read as private — not secretive, but neither crafted with an audience or a set art-historical lineage in mind.

Hurtado worked on four series simultaneously in the 1970s: geometric abstractions she painted as quickly as she could, sometimes embedding text in them; the “Light Portal Paintings,” small works on paper featuring white rectangles surrounded by color washes; foreshortened self-portraits that always exclude her face; and works in which bodies become landscapes with feathers floating in the sky. When I visited, examples from each of these series shared the floor, table, and wall space in the West Adams studio that stores her and Mullican’s work. Blue, gray, and black lines and circles loop together in one eight-foot-wide abstraction, Untitled (1973), but the precision of the rearranged composition undermines the looseness of the painted shapes. She cut the painted canvas into strips of varying width, rearranged them and sewed them back together, turning an impulsive-seeming experiment into a complex collage. On a far wall, the portal paintings recalled less-pristine James Turrell skyspaces (which he began building around the same time she painted these). Hurtado said she tried to paint light so well that it attracted moths, and the whimsy of that goal feels palpable in these works, with their idiosyncratic color combinations surrounding rectangles of clean white. While the portals and resewn abstractions experiment with space, mood, and color, the self-portraits and body-landscape hybrids are skillfully representational, evincing an allegorical quality as figures relate to domestic and natural surroundings.

Such variety in a studio practice has been more career curse than blessing, as ever-changing painter Dona Nelson, younger than Hurtado, discusses often. “A defined product means that you have your little corner of originality but really, it’s a more natural thing for human beings to criss-cross,” Nelson said in 1996.[3] Each of the shows Hurtado appears in this summer feature the self-portraits or body-into-landscapes. This means unfamiliar viewers will receive a piecemeal introduction to her work, one that highlights an exploration of the personal that coincided with Hurtado’s first encounters with feminism.

When I first spoke with Hurtado in 2016 she explained that, before she joined the women’s groups, she would turn her unfinished paintings to the wall when people came over. This stopped in the 1970s, and while she does not call herself a feminist artist, she embraced the self as subject matter more confidently in the wake of her encounter with the women’s movement.

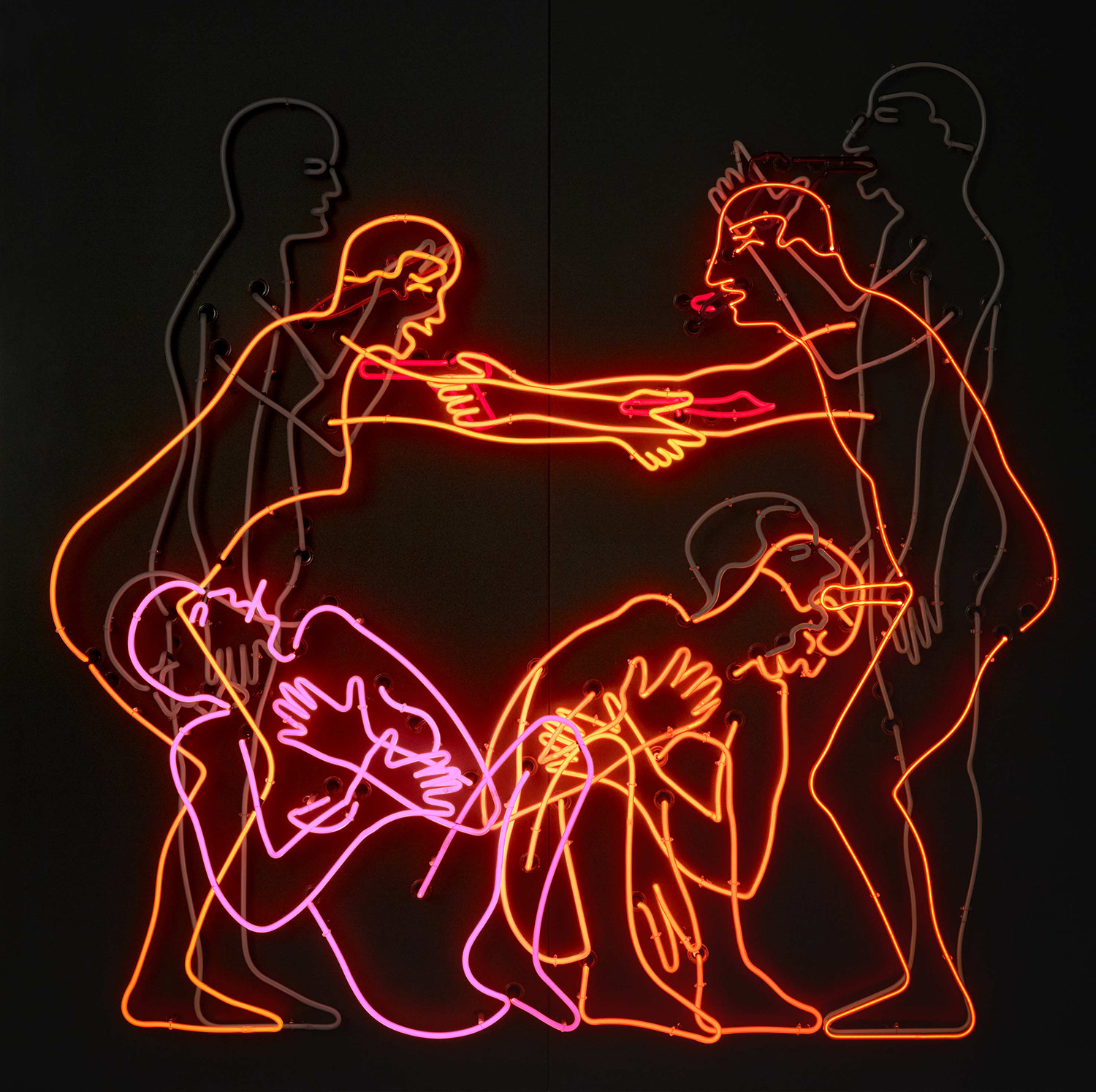

Joyce Kozloff, whose own work treats the language of craft as a sociological wellspring, moved to Los Angeles in 1971 and met Hurtado when she invited all the female artists she knew of to a consciousness-raising gathering at her apartment. “We went around and introduced ourselves,” recalls Kozloff. “Hurtado proudly said, ‘I’m Luchita Hurtado,’” though she’d gone by Mullican until then. Kozloff, who donated Labyrinth Unfathomable, an undated ink drawing by Hurtado of intertwined, ribbon-like figures to Smith College in February, recalls the work shifting as Hurtado’s life did. “It paralleled what was going on around her,” she says. It’s the 1970s self-portraits that stand out to her most clearly: “the paintings looking down at her own body, standing on a woven carpet, perhaps, her feet and stomach visible.” Bruria Finkel, an artist and curator who also met Hurtado during the women’s movement in Los Angeles, remembers the 1970s self-portraiture best as well, describing one painting in which there is “a cigarette being lit and offered and all she concentrates on is the hand, the cigarette, and the shoe.” This, Finkel observes, “creates a complete landscape of the moment.” Treating her own body as viewfinder, Hurtado connects the personal with the contextual in such a way as to make them appear interdependent.

In Self-Portrait (1971), a wooden toy car interrupts a tiled black and white floor, rendered in oil and graphite. Two figures appear in this painting, both nude and foreshortened, like they’re pointing cameras down at themselves. She doesn’t recall now if she meant both figures to be herself, but they appear to be in conversation, or confrontation, stepping toward each other. Another self-portrait from this era, Untitled (1969), she made in a closet, a thin line of light shining from under the half-open door and bisecting the Native American rug on which she stands. She holds her hands out, palms down, as if steadying herself. Curator Dextra Frankel, who put one of Hurtado’s self-portraits in the 1972 exhibition “Invisible/Visible: 21 Artists” at the Long Beach Museum of Art, wrote in the catalogue that the artist “looks down and sees herself in a way men never see women.”[4] This is literally true, since Hurtado painted herself from her own perspective with no mirrors or cameras to aid her, but the exclusivity of the female perspective seems far less important in this series than understanding the body in context. Her body multiplies and moves from confined domestic spaces into public, wide-open spaces, acting as a sincere pre-selfie browser that brings its vulnerability with it everywhere.

In an undated self-portrait from the 1970s, the space around her body dissolves into blue sky and baseball players freeze mid-game on her torso. “I’ve always had a sense of humor,” said Hurtado, who mostly talks about her work in generalities these days: “My thoughts have always been that my body is just on loan to me, that I better take care of it because I have to give it back.” While she is happy to discuss her brushes with Surrealists, Dynaton, and feminist artists, she frames her own individual works as instances in a life-long, circular quest to understand the world. Maintaining the close connection between the evolution of her life and her work became her methodology.

There is in this an echo of the work of artists like Lee Lozano or Linda Montano who, through conceptual practices and performance, experimented with “life as art,” rendering their lives a medium resistant to commodification. “The work is so personal” is something said often about women who folded their vulnerabilities, erotic observations, and personal lives into their formal explorations before feminism punctured the Western art world. Scholars describe the work of late artist Carol Rama, who had her first retrospective in 2016 at age ninety-six, as highly personal, partly because she always framed art as a therapeutic obsession. I assumed Dorothy Iannone was young after first seeing her sexually explicit sculptures, because they defied my expectations of someone in her eighties, groomed around Abstract Expressionists. Likewise, Tracy Emin thought Louise Bourgeois was Emin’s own age when she first saw the work in the early 1990s — its comfortability with emotion and self-exposure felt new, because its prominence in major mainstream exhibitions was. Hurtado’s self-portraits perhaps appeal so much right now because they, like work by a handful of “rediscovered” women born earlier in the twentieth century, recognize the usefulness of the personal as an entree into bigger subjects. But framing it like this, as a forerunner to the feminist art we value now, undermines the breadth of her art.

Hurtado acknowledges all the movements, critical frameworks, and histories with which she interacted, but doesn’t accept any one of them as her defining story, instead preferring a wide-open narrative of the work.

Two months ago, in front of a crowd, Hans Ulrich Obrist asked her about historical icons: “Can you tell us about your meeting with Duchamp?” Her answers favored sensations and minutia: “Well I was already in my nightgown and he arrived and I […] put on my dressing gown and I went out and I didn’t have any shoes on and I sat on a bench and he came and sat next to me and began to massage my feet.” When Obrist asked her about the Dynaton group, to which two of her husbands belonged, she recalled Isamu Noguchi saying Paalen had the intellect and Mullican the talent. “[Y]ou know you can’t do that to people, say someone is greater,” she said. “Things change.”