Philosopher Gilles Deleuze heeded the visionary philosophers — those he saw as seers — and considered Spinoza a vivant voyant [living seer]. Spinoza, himself, referred to his geometrical demonstrations of his Ethics as “the eyes of the soul.” 1 This radical thinker of democratic principles formulated his ethics not on rationality but on a reasoned awareness of both passive and active emotions — something akin to what Freudian psychology would later term as conscious and unconscious drives.

Deleuze also saw Michel Foucault as a seer, a visual historian adept at asking questions, particularly toward discerning the truth of our relationship to the world around us. Foucault understood that visualizing the world has its own history, and that “seeing” is an important facet of philosophical practice.2 For Foucault, making things visible is a historical practice; uncovering the underlying, unseen motivations and procedures is a critical one.3 Such is the work undertaken by the artist Alfredo Jaar, especially if we consider “The way it is. An Aesthetics of Resistance,” his three-venue retrospective organized by the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK).

Structured with regard to chronology, subject and scale of projects, each venue is designed differently for information, impact and reflection. The section of the exhibition at NGBK offers an intimate display of works about Chile, while an intervention disrupts the sobriety of the 19th-century halls of its second venue, the Alte Nationalgalerie, and major project groups for which the artist is best known infiltrate with searing light and somber shadows its third venue, the Berlinische Galerie. It makes little difference in what order one visits the three venues, but given that the NGBK galleries include early works by a young Chilean artist coming of age in the restrictive environment of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial oppression, this is arguably the place to begin.

Site of an encounter

Jaar’s first work as a young artist records the fateful moment of the bombing of La Moneda Palace by the Chilean Armed Forces in a coup against a democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. A set of numbers, letraset on cardboard, designate a moment — 11.09.73.12.10 (1974), a Chilean September 11 that would later be historically displaced as “small 11” after the events of “11 grande” in 2001, just as South America is displaced in global parlance to the greater hegemonic authority of its northern neighbor “America.” 4 Jaar was only seventeen years old at the time. He would soon study architecture, and later film, but he thought of himself as an artist, yet without any defined preconception of what “art” could be. Concerned with neither aesthetics nor formal qualities, he instead began with indignation, ideas and a project-based methodology to execute them.

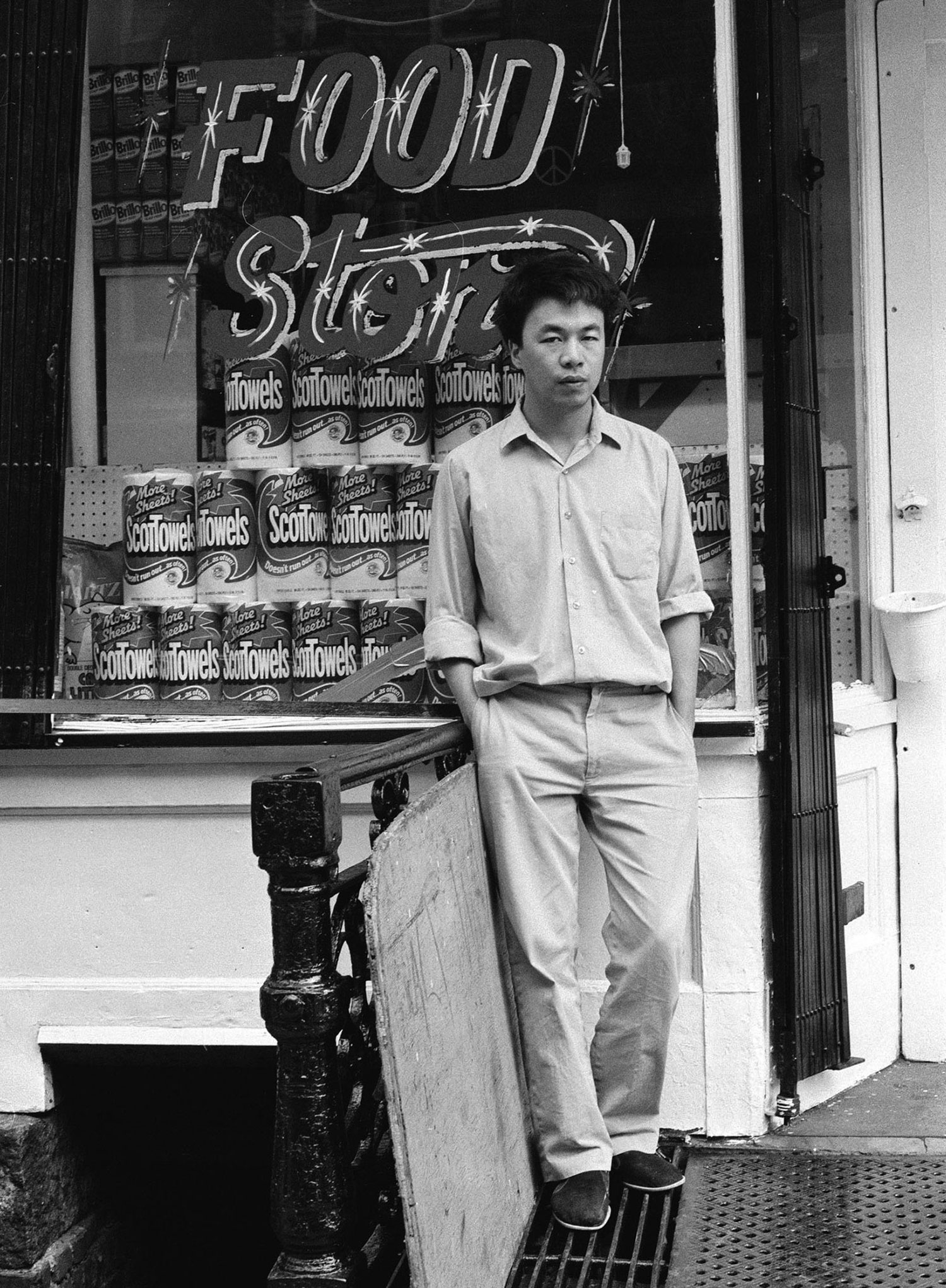

Working within the confines of censorship, Jaar exhibited a sensibility tuned to the gaps, blind spots and silences that media representations leave in their wake. He developed a way of working to imply that which is unspoken — Studies on Happiness (1978-1981); to expose that which is hidden — Searching for K (1984) and Nothing of very great consequence (2008); and to perform an acknowledgement of that which is forgotten — Opus 1981, Andante Desparado (1981), Faces (1982) and Fragments (2010). A half dozen works, shown here for the first time, reveal Henry Kissinger’s cynical role in regime change in the ’70s. In a telephone transcript, shown as a black-and-white transparency in a light box, Kissinger refers to the Chilean coup as “Nothing of very great consequence,” then assures President Nixon that “our hand doesn’t show on this one though.”

With Studies on Happiness, Jaar did not wait for cultural spaces to welcome him but created works in public using the spaces and methods of advertising by asking passersby, “¿Es usted feliz?” [Are you happy?]. It is an honest question and a good place to begin. You wouldn’t ask it of a government official or even a colleague; it is a question you ask a friend and, as Adriana Valdés reflected while speaking with Jaar, friendship is hard to come by and trust difficult to sustain during a dictatorship.5 It is a question that conflict makes superfluous yet all the more necessary for its compassion.

How can one disrupt that which is anticipated in order to see differently that which is there? This is a problem posed by Brecht in theater, and Jaar applies it to reconfigure the signs and symbols of civic identity — names, flags and logos — to question the basis of personal identity. Chile 1981 (Before Leaving) plants a sequence of Chilean flags into the earth, bisecting the country in two until they lead into the sea: a vision of exodus, suicide and, later, when revelations came to light, the fate of the desaparecidos, opposition activists dumped from planes and helicopters to “disappear” into the sea. After leaving Chile in 1982, Jaar would continue to question political and cultural hegemony by world powers in works as divergent as A Logo for America (1987) and Gold in the Morning (1987).

To do this, he developed a number of visual strategies that included appropriation, fragmentation and reflection. 1+1+1 — originally produced for Documenta 8 in 1987 where it brought Jaar international critical acclaim — uses all three. In Berlin, it is installed as a kind of agonistic debate with the 19th-century realism of the Alte Nationalgalerie. Three images of impoverished street children from El Salvador, culled from the media, are bisected, their lower halves placed in relation to a sequence of gold frames — emblems of a bleak reality of the so-called Third World in confrontation with proxies of the wealth and culture of the First World. Only in the third configuration, where a mirror reflects the image within the frame, do the two realities meet. “The mirror is where we compose our identities every day before going out,” Jaar contends: “It defines our identity — who we are and who we want to be in the world — and suddenly here in this work the mirror becomes the site of an encounter.” 6

An emergency

Deleuze read the work of philosophers in terms of their ways of seeing; art has always been about looking, but since Manet, and for Foucault since Velásquez, there has been a self-conscious awareness of the connection between seeing and representation. In a post-Kantian response, philosophers like Foucault, Jean-Luc Nancy and Jacques Rancière considered actively the work of artists; and artists like Jaar, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Martha Rosler became readers of philosophy and political theory. This, too, is an encounter and an exchange, precipitated by an emergency.

The Berlinische Galerie offers the most extensive look at the artist’s mature work, including projects from the last two decades that collectively underscore the role of the artist as public intellectual. How do we know the world? Jaar has the conviction that the manner by which we know influences the veracity of what we know: how we represent, understand and respond to information in turn influences how we engage with others. “In a lot of my work, I am a frustrated journalist. I am trying to inform and inform and inform. I have carried that weight on my shoulders all my life,” he said in 2008.7

In a world of increasingly rapid and abundant communication, we as consumers of information become overwhelmed and learn to shut out, glance aside and ignore events Jaar decries as public emergencies: Stop! Can’t you see what is happening? He leads us to Rwanda, but also to the problems of picturing genocide; he points out racism, but also the difficulty in accepting our own prejudice; and he asks us to consider a world both replete and devoid of images, but also the choices we make in response to them. Jaar deliberately blinds our vision with glaring light. Then he asks us to look again, differently. Light seen as metaphor and as a jolt to our perception, image seen as reality and as afterimage, an impression on our soul. Visibility, according to Foucault, is a matter of methodology: how we transform that which constrains our thinking.8

In The Rwanda Project (1994-2000), Lament of the Images (2002) and The Sound of Silence (2006) the artist uses an architectural vocabulary of scale, light, movement, space and tension to create environments of contemplation. He uses principally light to hold us captivated in place. For The Eyes of Gutete Emerita (1996) a million slides are piled upon a light table — the only light in a darkened room — with a few slide-viewers to look eye-to-eye as it were at any individual image. They are all the same: a close-up of the eyes of a Tutsi woman who has witnessed the slaying of her husband and sons by Hutu forces while she and her daughters managed to flee into the brush where they hid for weeks until the frenzied killing had subsided. By then nearly a million individuals had been brutally massacred, represented here not by the dead but by the eyes that witnessed and survived. The piece is exacting, connoting endless images unheeded, infinite words unheard, souls tossed in a heap.

An intervention

“And so, in the dim light, we gazed at the beaten and dying… We looked back at a prehistoric past, and for an instant the prospect of the future likewise filled up with a massacre impenetrable to the thought of liberation. Heracles would have to help them, the subjugated, and not those who had enough armor and weapons.” 9 Peter Weiss’s description of the mythological drama — represented through the sculptural tension of the Pergamon Altar — depicts Heracles as a visionary with the strength and determination of a warrior. All massacres are prehistoric in being senseless and without cognition of history; but all massacres occur in a history prefigured by a profound devaluation of human life and welfare. It takes warriors and intellectuals to change the odds.

The Pergamon Project / An Aesthetics of Resistance was created in 1992 by the artist after a year-long residency in Berlin. Compelled by a series of reprehensible racist attacks against immigrants, he took inspiration from Weiss’s novel, The Aesthetics of Resistance (1975-1981). On the famed steps of the classical altar, Jaar placed in white neon the names of German cities and towns where immigrants had been the targets of hate crime. These names now line the upper walls of the Berlinische Galerie with three added in red neon in 2012, reminders that the crimes continue. “Don’t just think like an artist: think like a human being,” Jaar intones during a conversation with Adriana Valdés.10 In The Pergamon Project, he suggests that we are all victims and perpetrators at variable points in our lives. But can he, like Heracles, change subjugation into action?

Jaar has often said in regard to his own work that he has failed — but is this technical failure? His work as an “architect” is honed and considered; he knows his margin for error. In its barest précis: Jaar excavates and lays bare the politics of the image; he dissects perception and representation, and he offers an alternative image of ethical relations. At times, as a response, his language succumbs to the vocabulary of victimization, and if not for his public projects, difficult to unveil in a museum setting, the enormous impact of his work as art might not transform into a means to generate self-reliance and respect. Outside the perimeters of a retrospective, 50 public projects in 30 years turn passive reception into active participation within local communities. Time and time again, we fail in our relations to others, but don’t give in, Jaar insists. When we fail to see, hear and act, we must continue to resist.

Space for breath

There is also need for recovery — “looking for breathing spaces,” he acknowledges.11 A space for breath is the pause we must make to stave off the paralysis of anxiety; this is the intake valve to imagine something other than perpetual hatred, revenge and victimization. In Opus 1981, he blew inexpertly into a clarinet until breathless and defeated. Later in Rwanda, he intuitively sought visual respite from the horrors of genocide in Field, Road, Cloud (1997) and Embrace (1995). This gesture is repeated in the more recent Kigali (2008). These quiet works neither efface the horror that is within our field of vision nor give us the opportunity to look away. Instead, they offer us the strength to see. They are the eyes of the soul and a means of restitution. This is Alfredo Jaar not as hero but as human being and friend.