Art is finally returning to its internal motives, the reasons which constitute its workings, its place par excellence, the labyrinth — the ‘inside work,’ the continuous digging inside the substance of painting. The idea of art in the ’70s has been to rediscover within itself the pleasure and the peril of getting your hands dirty, and rigorously so, in the substance of personal imagery, made up of driftings-off and elbowings-in, approximations and never-definitive landings. The work becomes a nomad’s map of the progressive movements practiced outside of any direction preconstituted by artists, the seeing-blind, wagging their tails around the pleasure of an art that doesn’t stop at anything, not even history.

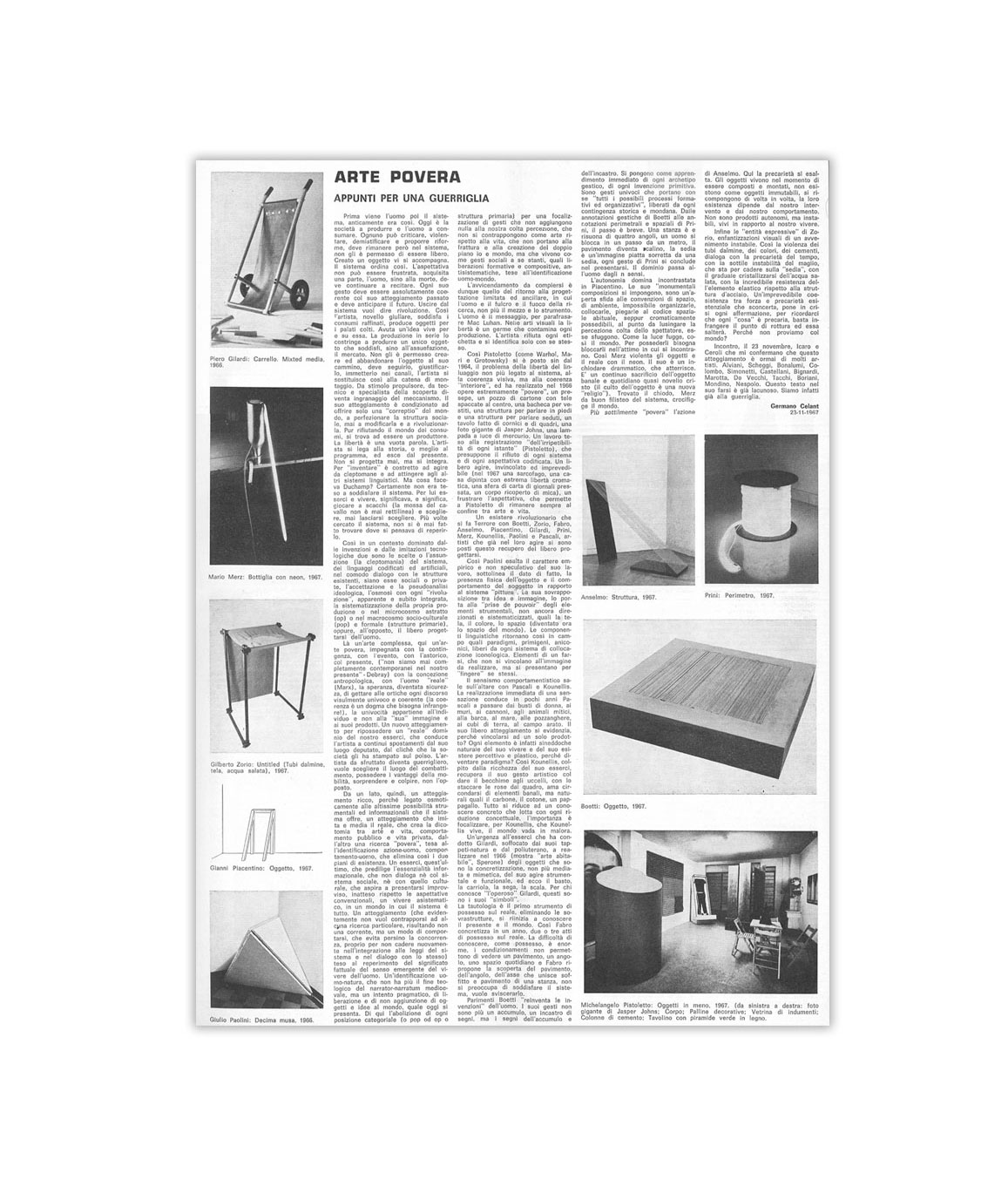

Art in the ’60s, including that of the avant-garde, has had a moral character: in its critical design, the formula of the Italian Arte Povera pursued a repressive and masochistic line, fortunately contradicted by some artists’ works. Later on creative practice did away with the formal censorship related to artistic production to favor the practice of opulence as amends for an initial loss, an access that means neither asceticism nor renunciation, but growth and development of the capacity to become a land-owner, at the limits of a possession put into continuous debate by the work’s and the artist’s natural movement of dispossession and overcoming.

Its opulence consists in its capacity to invest an initial loss, in the nocturnal condition of the day-to-day, with the risk of a solar practice of art. Finally pictorial practices are taken up as an affirmative movement, as a gesture which is no longer one of defense, but of active, daytime, fluid penetration.

The initial precept is that of art as the production of a catastrophe, a discontinuity that destroys the tectonic balance of language to favor a precipitation into the substance of the personal imagery, neither as a nostalgic return, nor a reflux, but a flowing that drags inside itself the sedimentation of many things which exceed a simple return to the private and the symbolic.

By definition the avant-garde has always operated within the cultural pattern of an idealistic tradition which tends to shape the development of art into a progressive, continuous and rectilinear line. The ideology which subscribes to this mentality is ‘Linguistic Darwinism,’ an evolutionary idea of art ascertaining a tradition in the linguistic development from our avant-garde ancestors up to the latest outcomes of artistic research. This position’s idealism lies in its consideration of art and its development apart from the blows and counterblows of history, as if artistic production were torn away from history’s more general production.

Until the ’70s, avant-garde art maintained this mentality, operating within the philosophic theory of ‘Linguistic Darwinism,’ of a cultural evolution respectful of every genealogy with a purist and puritanical punctiliousness. This caused an artistic and critical production careful of getting trapped into the geometric rut, subject to its continuity. As their final aim, the neo-avant-garde tried to save the artist’s ‘happy conscience,’ entirely based on the internal consistency of his work, realized within the experimental limits of language, against the negative inconsistency of the world.

Such a theory causes that coercion to be new, which characterized artistic production in the ’60s, an activity circumscribed to language which promoted the need to experiment with new techniques and new methodologies in the face of a dynamic reality, experimental in and of itself in its productive capacity and in its developments of tendencies of thought.

Artists in the ’70s begin to operate at the very point where the coercion to be new ceases, at the moment of the productive slow-down of economic systems, when the world is entangled in a series of crises stripping the productivistic giddiness of all of its ideological systems. Finally, talk has been heard and is still being made of a crisis in art. However, if by crisis we intend, according to the etymon, ‘breaking point’ and ‘verification,’ then we can use the word as a permanent angulation to verify the real stuff of art. The definition of crisis in art refers to two levels: the death of art and the crisis of the evolution of art.

In Hegelian terminology, however, the death of art means the bypassing of the categories of artistic working by philosophy, the science of thought which includes and absorbs artistic intuition. More recently, the death of art refers to the realization that such an experience can no longer corrode the various levels of reality. If on the one hand the impotence of the superstructure (art) compared to the structure (the economy, politics) is underlined, on the other we can ascertain the fall in artistic production from quality (value) to quantity (merchandise).

Today the crisis in art in its strictest sense means the crisis in the evolution of the artistic language — the crisis in the avant-garde’s Darwinistic and evolutionary mentality. This critical moment is overturned in terms of new operability by the artistic generation of the ’70s. They have unmasked the progressive valence of art, demonstrating how in the face of the unchangeability of the world, art is not for progress but rather progressive with respect to its consciousness of both its own and circumscribed internal evolution.

Now the scandal paradoxically consists in the lack of novelty, art’s capacity to achieve a biological respiration of speedings-up and slowings-down. Novelty is always born of a market demand for the same merchandise but in a transformed shape. In this sense many poetics and their relative subgroups were burned in the ’60s. Because through their poetics, the sub-groups permit the constitution of the notion of taste which, by reason of sheer quantity of artists working in the same direction, allows the social and economic consumption of art.

Finally the poetics have been thinned out, every artist working on an individual research that shatters social taste and pursues the finality of the work itself. The value of individuality, of working by oneself, is contrary to a social system crossed by superimposed totalitarian systems, political ideology, psychoanalysis and the sciences, all of which resolve the antinomies and swerves, produced in the forward movement of reality, inside their own viewpoints, their own projects. Inside a concentration camp which cuts down on its own expansion and tends to reduce all desire and material production of its own torturous and impregnable routes, a culture of forecasts has to tighten its belt. The religious system of ideologies, of psychoanalytic and scientific hypotheses, tends to transform all that is different into something functional to the system, recycling and converting into terms of functional and productive all that is instead rooted in reality.

That which cannot be reduced to these terms is art, which cannot be confused with life. Art instead serves to push existence towards conditions of impossibility. In this case impossibility refers to the possibility of keeping artistic creativity anchored to the project of one’s own production. The artist of the ’70s is working on the threshold of a language which cannot be reduced to reality, under the impetus of a desire which never changes in the sense that it is never transformed except in its own appearance. In this sense art is biological activity, the applied activity of a desire which only lets itself be ratified according to its image and not its motivation. Art does not accept transactions, conjugated inside the artist’s need to make the relative data of current production absolute and to create discontinuity of movement, while the austere immobility of the productive concept exists.

Today art is not the artist’s insertion of remarks within the territory of language, never dual or specular with respect to reality. In this sense the production of art by the ’70s generation moves along paths which require other disciplines and other concentrations. Here concentration becomes deconcentration, the need for catastrophe, breaking with social needs. Artistic experience is a necessary lay experience that confirms the essentiality of breaking-off, the incurability of every fragment, of the impossibility of recreating unity and balance. The work becomes indispensable because it concretely re-establishes breakings-off and imbalances in the religious system of political, psychoanalytic and scientific ideologies, which tend to reconvert the fragment in terms of metaphysical totality.

Only art can be metaphysical because it succeeds in transferring its ends from outside to inside itself in its possibility of establishing a fragment of the work as a totality which recalls no other value outside of the fact of its own appearing.

Basically art finds inside itself the strength to decide the store from which to draw the energy necessary to construct its images, and the images themselves are an extension of the individual’s imagery that rises to an objective and ascertainable level through the intensity of the work. Because without intensity there is no art. Intensity is the work’s ability to offer itself, or what Jacques Lacan calls the “gaze-tamer,” its capacity to fascinate and capture the spectator inside the intense field of the work, inside the circular and self-sufficient space of art functioning according to internal laws regulated by the demiurgic grace of the artist, by an internal metaphysics which excludes any outside motivation.

The rule and motivation of art is the work itself, imposing the substance of its own appearing, made up of material and shape, of thought directly embodied in painting, and the sign, unpronounceable without the help of the grammar of vision.

In this way in the ’70s appear deliberately shattered, disseminated in many works, each one carrying within itself the intense presence of its own existence, regulated by an impulse circumscribed to the singularity of the work created. Thus is delineated the concept of catastrophe, the production of discontinuity in a cultural fabric held up in the ’60s by the principle of linguistic approval. The internationalistic utopia of art characterized the research of Italian Arte Povera, bent on smashing national borders, thereby losing and alienating the deepest cultural and anthropological roots.

In opposition to the apparent nomadism of Italian Arte Povera and the experiences of the ’60s, based on the recognition of methodological and technical affinities, the artists of the ’70s respond with a nomadism both diverse and diversifying, playing on the sensitivity and the swerve between one work and another.

The unexpected landslides of the individual’s imagery preside over the artistic creativity previously mortified by the impersonal, synchronic character and even by the political climate of the ’60s, which preached depersonalization in the name of the supremacy of politics. Now instead art tries to repossess the artist’s subjectivity, to express itself through the internal form of language. The personal acquires an anthropological valence because it participates in bringing the individual, in this case the artist, back to a state of renewal of a sentiment towards himself.

The work becomes a microcosm which grants and establishes the opulent capacity of art to repossess, to return to being a land-owner, of a subjectivity fluid up to the point of entering the folds of the private as well, basing the values and the motivations of its working in every case on its own pulsion.

The ideology of Italian “poverismo” and the tautology of Conceptual art are bypassed by a new attitude which preaches no pre-eminence outside of that already inside art and in the work’s flagrant rediscovery of the pleasure of showing itself off, of its own texture, of the substance of the painting unencumbered by ideologies and purely intellectual worries. Art rediscovers the surprise of an activity infinitely creative, open even to the pleasure of its own pulsions, and an existence characterized by thousands of possibilities, from the figure to the abstract image, from a flash of genius to the delicate texture of the medium, which all simultaneously cross each other and drip in the instantaneity of the work, assorted and suspended in its generously offering itself as a vision.

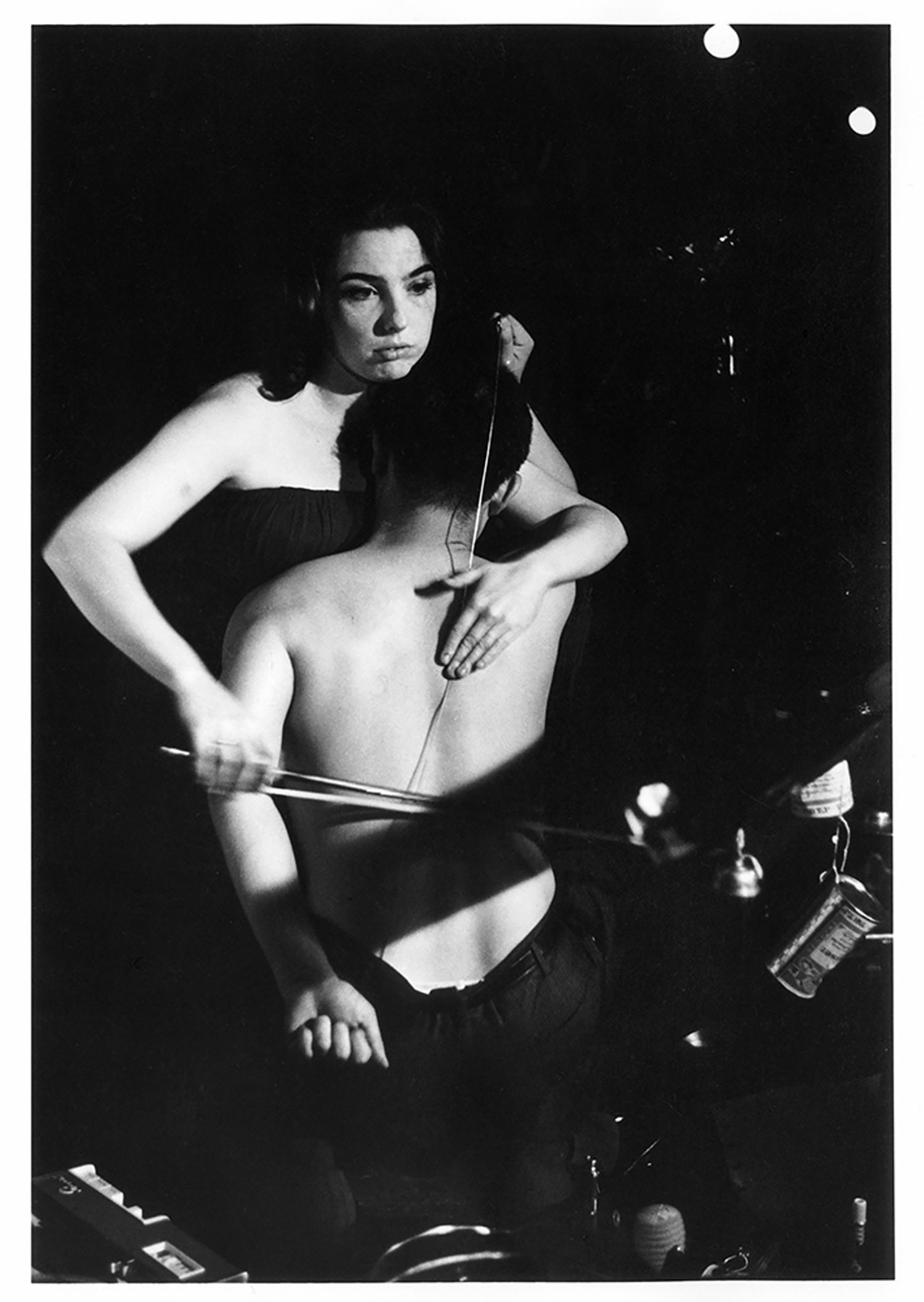

In its nomad creativity, art in the ’70s has found its own movement par excellence, the possibility of unlimited free transit inside all territories with open references in all directions. Artists like Marco Bagnoli, Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Nicola De Maria, Mimmo Paladino and Remo Salvadori work in the mobile field of the Trans-Avantgarde, meaning the crossing of every experimental notion of the avant-garde according to the idea that every work presumes an experimental manuality, the artist’s surprise at a work no longer constructed according to the certainty expected of a project and of an idea, but which forms itself before his eyes under the pulsion of a hand which dips inside the substance of art in a personal imagery embodied somewhere between idea and sensitivity.

The notion of art as catastrophe, as an unplanned accident making each work different from the rest, creates a movability for young artists, even within the limits of the avant-garde and its traditions, no longer linear but made up of returns and projections ahead, according to a movement and a vicissitude which are never repetitive since they follow the sinuous geometry of the ellipse and the spiral.

The Trans-Avantgarde means taking a nomad position which respects no definitive engagement, which has no privileged ethic beyond that of obeying the dictates of a mental and material temperature synchronous to the instantaneity of the work.

Trans-Avantgarde means opening up to the intentional check-mating of Western culture’s logocentrism, to a pragmatism which returns space to the work’s instinct, not a pre-scientific attitude but if anything the maturing of a post-scientific position which exceeds the fetishistic adjustment of contemporary art to modern science: the work becomes the moment of an energetic functioning which finds the strength to accelerate and to achieve inertia within itself.

Thus question and answer come to a draw in the image match, and art bypasses avant-garde production’s feature of setting itself up as an inquiry, ignoring the spectator’s expectations in order to arrive at the sociological causes provoking them. Avant-garde art always presumes discomfort and never the happiness of the public, obliged to move out of the field of the work to understand its complete value.

The artists of the ’70s, whom I call the Trans-Avantgarde, have rediscovered the possibility of making the work clear through the presentation of an image which is simultaneously enigma and solution. In this way art loses its nocturnal and problematic side, its pure inquiry, in favor of a visual solarity which means the possibility of realizing works well-made, in which the work really functions as a “gaze-tamer,” in the sense that it tames the restless glance of the spectator, used to the avant-garde’s open work, the planned incompleteness of an art which needs the spectator’s intervention to be brought to perfection.

Art in the ’70s tends to bring art back to a place of satisfying contemplation where the mythic distance, the far-away contemplation, is brimming over with eroticism and energy originating in the work’s intensity and in its internal metaphysics.

The Trans-Avantgarde spins like a fan with a torsion of a sensitivity that allows art to move in all directions, including towards the past. “Zarathustra wants to lose nothing of mankind’s past, he wants to throw everything into the crucible” (Friedrich Nietzsche). This means not missing anything because everything is continually reachable, with no more temporal categories and hierarchies of present and past, typical of the avant-garde, having always lived the time to its back as archaeology, and in any case as evidence to reanimate.

The work of Marco Bagnoli is an investigation of the physical and mental quality of space and time in their interactions and in the open dialectic of multiplication (space times time). An analysis of the concept of limit, of the interstice as the germinal place of differences and oppositions. The principle of centrality is shattered to favor oblique and mobile relations.

Sandro Chia practices, through painting, the theory of a manuality aided by an idea, by putting to work a hypothesis formulated in the particularity of a figure or a sign. If the image constitutes on the one hand the unveiling of the idea, on the other it’s also evidence of the pictorial procedure that produces it and unveils its internal circuit, the complex range of reflexes, possible correspondences, the shiftings and cross-references between different polarities.

Francesco Clemente works through repetition and shifting. He sets out with a pre-existent image which he reproduces in painting. However, every successive reproduction is altered and moves away from that which is being reproduced according to variations as subtle as they are unpredictable. An expected certainty is at the basis of the work, which in being effected implies a swerve away from the initial norm. This shifting occurs through oblique lines, a tangible sign of the production of difference.

Enzo Cucchi accepts the movement par excellence of art, inscribing the ciphers of his own personal language under the sign of inclination, where no stasis exists but rather a dynamic of figures, signs and colors which reciprocally cross and drip into the sense of a cosmic vision. The painting chews up and absorbs the crash of various elements into the picture’s microcosm. Thus, together the microcosm and macrocosm complete a crossing where chaos and cosmos find the deposit and the energy of their combustion.

Nicola De Maria works on the progressive displacement of sensitivity, practiced through the instruments of a painting which tends to offer itself as the exteriorization of a mental state and as the interiorization of possible vibrations which are born during the execution of the work. The result is the foundation of a visual field, of a vision at the intersection of many different points, in which sensations find a spatial extroversion until they resolve themselves into a kind of interior architecture.

Mimmo Paladino exercises a painting of surfaces, in the sense that he tends to deliver all sensitive data, even the most internal, to a visual emergency. The painting becomes a meeting and expansion place in the range of vision of cultural motives and sensitive data. Everything is translated into terms of painting, sign and matter. The painting is crossed by different temperatures, hot and cold, lyric and mental, dense and rarefied, which surface at the end of the color’s gauging.

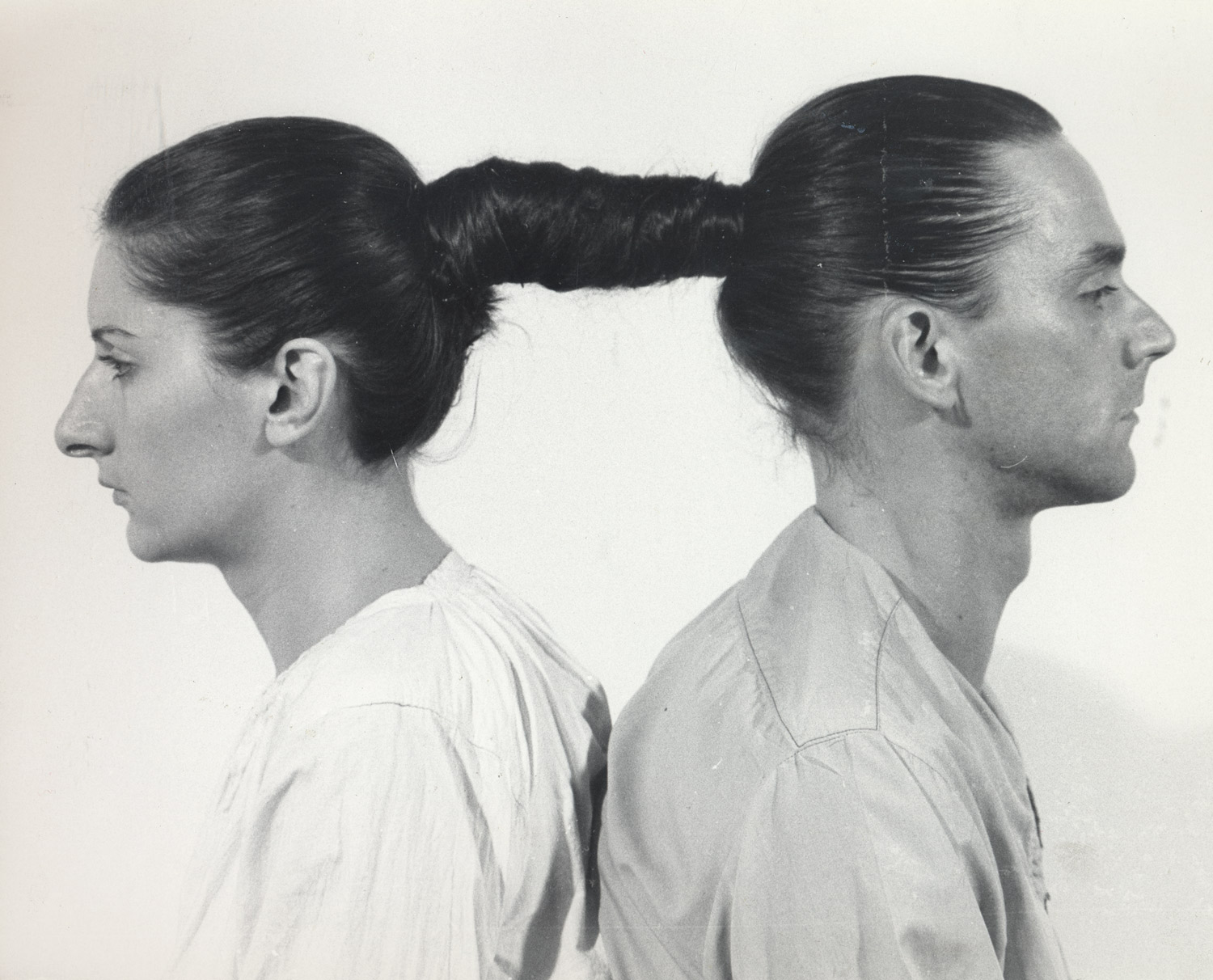

Remo Salvadori carries out a work mainly on the theme of the double, the splitting of unity as the presence of two opposite unities: the male element and the female, the front and the back. The line of the diaphragm which separates and differentiates the identity and the resemblance can be approached in the median, generating the faces of symmetry and situating them on opposite and irreconcilable planes.

Today to make art means having everything on the table in a revolving and synchronous simultaneity which succeeds in blending inside the crucible of the work both private and mythic images, personal signs tied to cultural and art history. This crossing also means not mythicizing one’s self, but rather inserting the self onto a collision course with other expressive possibilities, thereby accepting the possibility of putting subjectivity at the intersection of all. “Being is the delirium of many.” (Robert Musil)

The shattering of the work means shattering the myth of the unity of the ego, assuming the nomadism of a non-stop personal imagery without anchorage or reference points. All this reinforces the notion of Trans-Avantgarde since it overturns the avant-garde’s attitude of having privileged reference points.

Every work becomes a vicissitude carrying and returning to the place of work, crossing multiple fields of reference, using every utensil, a manual capability oriented by the grace of color and of many mediums, a thinker who thinks directly through images and crouches down to the bottom of vision, like a temperature which acts as an adhesive, allowing the work’s fragments to maintain a mobile relationship which is never bolted and never seeks shelter in the idea of unity.

No demiurgic rule exists — only the creative practice of an art which stabilizes all precariousness without transforming it into stabilization and symbolic fixity. The work preserves the flow of its process, of its being active on the outskirts of a subjectivity which never tends to become exemplary but rather preserves the character of an accident, of an opening in a field — not the avant-garde’s romantic intoxication with the infinite, but moving without a center along drifts marked by a unique perspective: mental and sensorial pleasure.

from Flash Art n°92-93, 1979