May 27, 2013: On the train from Rome to Venice, I kill time studying other passengers’ features and behaviors, trying to pick out those who, like myself, are going to the 55th Venice Biennale. During the entire trip, along with the rocking of the Freccia d’Argento, we are accompanied by the constant clicking of a camera. As if reenacting an Antonioni movie, a young Asian man ceaselessly documents his arrival in the Laguna. (Definitely a Biennale type, probably his first time.)

“The Venice Biennale is the Mother of them all” and “Italy is a republic founded on labor.” These two sentences buzz in my head, sounding like a dead language. First came the Venice Biennale, then São Paolo; after the Second World War came Documenta, helping Germany to overcome its Holocaust trauma. And finally the 1990s came along, as did the crazy swarm of contemporary art biennials, predominantly in emerging countries in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. The art tribes started to cheerfully migrate from one continent to another as if on an eternal spring break. As the meaning behind these all-inclusive exhibits began to dissipate, the contemporary art audiences only widened; however, within the system a massacre was at play: inclusion or exclusion, biennial or oblivion. For young artists, having a presence at the various biennials became essential for gaining critical recognition and market validation.

Massimiliano Gioni is a talented and ambitious young curator who began his career on the very pages of Flash Art. He has had a long, symbiotic, intellectual relationship with one of the most renowned Italian artists of the last twenty years: Maurizio Cattelan. In 2006, with Cattelan and Ali Subotnik, Gioni curated a very interesting Berlin Biennale. Since 2010, he has been Associate Director at the New Museum of New York. He is very close to the Greek collector and tycoon Dakis Joannou, one of the main financial backers of this Biennale. It is said that this year’s opening was pushed back to the last weekend of May in order to accommodate the migration of luxury gypsies — the hard core of the contemporary art system — to Hydra to celebrate Dakis and his bombastic eighties-born collection. Massimiliano dwells in the heart of this system and embodies everything a young curator would like to be; curiously, however, his exhibition was defined “an outsider’s Biennale.” In Venice I saw Gioni’s young colleagues vexedly swimming past, appearing slightly preyed upon while raving about the show. All this is to say that in some sense Massimiliano was able to capture the Zeitgeist quite well. I’m older and belong to the last generation of Italians who believed they could change the world. My political and intellectual background was shaped within the Italian student movement of 1977. What we inherited from the student movement of 1968 was merely the sentence “Immaginazione al Potere” [All Power to the Imagination].

We arrive in rainy Venice and, after a quick pit stop at the hotel, there’s the usual dance of accreditations (we have over a decade’s worth of experience at letting in our unaccredited friends). We make our way into the Arsenale. The exhibit opens with Marino Auriti and his Palazzo Enciclopedico, which gives the Biennale its title. Marino Auriti was a visionary architect who immigrated to the United States in the 1920s, and who lived his entire life working on a utopian project to gather into a single building all that is known to mankind. I think of other great Italian immigrant figures of different eras who, arriving in that promised land, sought refuge in utopia: Paolo Soleri who built the city of Arcosanti in Arizona, or Simon Rodia who built Los Angeles’s Watts Towers.

At first glance the Arsenale is looking good — the best it has ever looked. The spaces of the Arsenale are truly difficult for installing art; however, for this edition Massimiliano has collaborated with noted New York architect Annabelle Selldorf, who designed and renovated the gallery spaces of Hauser and Wirth, David Zwirner and Barbara Gladstone, among others. Selldorf deals with this space by counterbalancing it and turning it into a sort of white box reinterpreted with a touch of Palladian classicism, with recurring themes of entrances and exits within circular rooms. In spatial alignment with Auriti’s Palazzo Enciclopedico, we find Belinda, a half-formed, vertical, somewhat spiral-shaped sculpture by Roberto Cuoghi, which to some degree introduces the feeling of “being and nothingness” that will follow us throughout our visit to the 55th Biennale. Surrounding Auriti’s Palazzo Enciclopedico, the space opens up into a circular shape where beautiful black-and-white photographs by Nigerian photographer J.D. Ojeikere are on display. Born in the 1930s, his entire collected works, spanning forty years, were a meticulous catalogue of Nigerian women’s hairdos. At this point, the exhibit’s tempo is imprinted. As Hal Foster wrote in 1996, the artist as ethnographer guards us against the risk of narcissism and omnipotence hidden in the practice of self-othering. In his Biennale, Gioni has declared the curator as ethnographer of the artist as ethnographer.

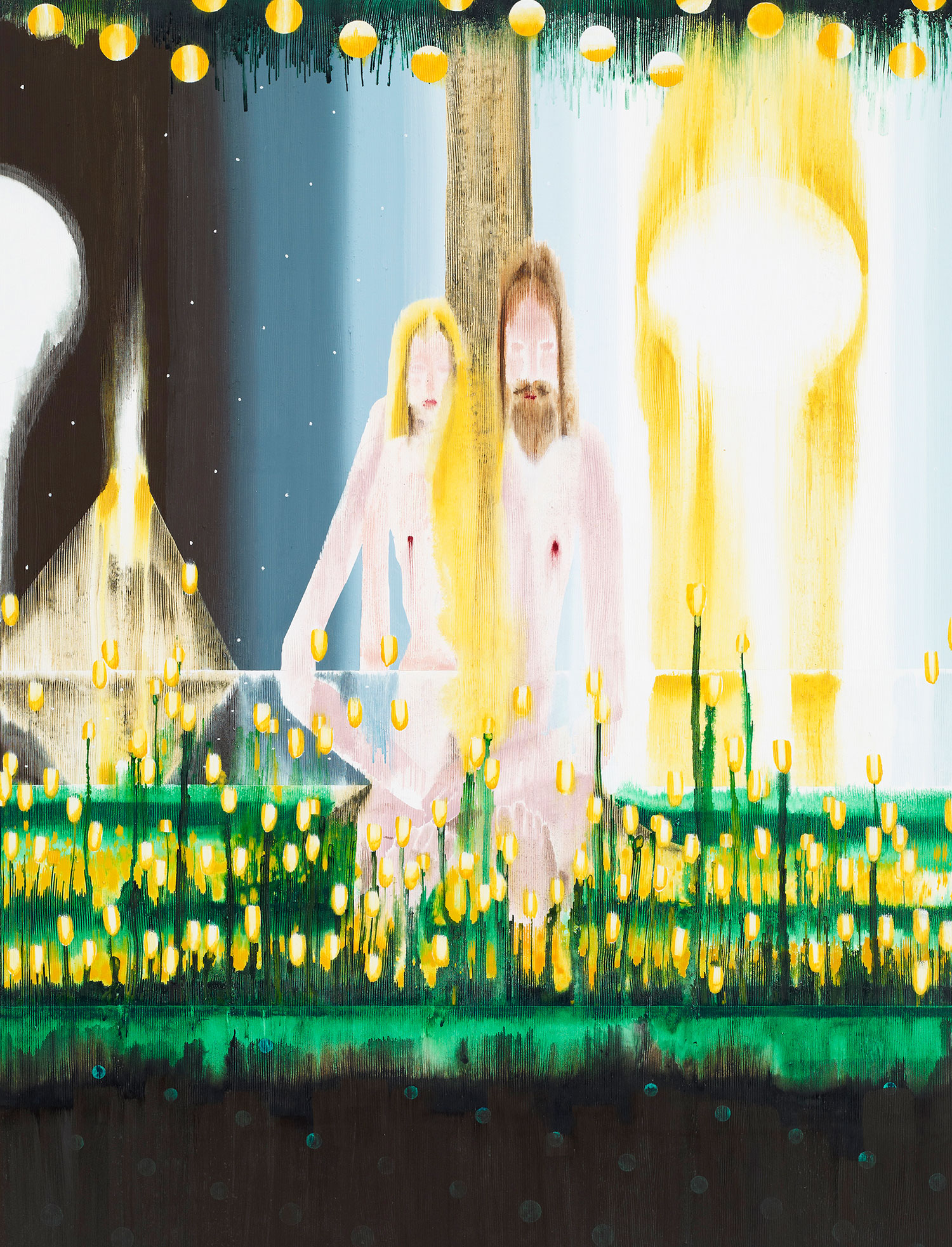

From the 1960s on, anthropology as a study of the Other has progressively become the lingua franca of art history and artistic practice in general. Camille Henrot is well aware of this. With her video Grosse Fatigue, winner of the Silver Lion, the French artist poetically analyzes the process of information accumulation and the impossibility of objective knowledge. The exhibit flows fluidly. Lin Xue’s drawings strike us with their impeccable calligraphy. They have a timeless dimension that transports us back to the Surrealists’ automatism. The great blobs of Phyllida Barlow appear, hanging clumsily — and slightly menacingly — from the ceiling. I see something very familiar that warms my heart — a room dedicated to Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. One of his painterly psychedelic explosions hangs in my living room in South Pasadena (few works hang on my walls; in fact, I have an odd psychological resistance when it comes to placing art in my home). Von Bruenchenhein, born at the beginning of the last century, died in the 1980s. He is one of those artists who received little recognition while alive, yet he worked ceaselessly, propelled by magnificent obsessions, free from the self-condemnation of finding consensus at any cost. So it is with many of the artists chosen for this Biennale. Gioni has brought great outsiders together with hipster artists and big-league galleries in an omnivorous operation that validates all and nothing.

The debate about the catalogue, the archive, the fabrication of personal genealogies, becomes almost implicit in any artistic practice of interest. By definition, an artist is a collector of images. Between the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, Aby Warburg’s “Mnemosyne Atlas,” composed in 1929, received renewed critical attention. In 1989, the first edition of Atlas, an impressive collection of images by the German painter Gerhard Richter, was published. In the early 1990s this collection of personal images heavily influence art produced by emerging artists, for whom the archive, its documentary material, became a style and no longer merely a source. I truly feel that Massimiliano’s “Encyclopedic Palace” should have included some of the first artists to confront this discourse at the beginning of the 1990s, such as Renée Green or Mark Dion, among others.

We make our way to the center of the galleries in the Arsenale and arrive at the heart of the show — the section curated by Massimiliano with artist Cindy Sherman. As I approach the three figurative sculptures that open this section — by Jimmy Durham, Paul McCarthy and John De Andrea — I have the sense of something that looks familiar but feels alien. I experience an uncanny feeling.

Massimiliano is a great admirer of Mike Kelley’s work, and, for good reason given the context, he originally wanted to include Kelley’s “Harems” in the exhibit. The “Harems” are probably Kelley’s most personal works, wherein all objects collected by the artist, from childhood through adulthood, are divided into eighteen categories: from rock collections to vinyl records and business cards. Kourosh Larizadeh of Los Angeles, who owns this artwork, was personally very close to Kelly and ultimately didn’t consent to the requested loan. The “Harems” were part of “The Uncanny” show, curated by Kelley himself, originally in 1993, which he proposed again in a more completed version at the Tate Liverpool in 2004 as well as at MUMOK in Vienna in the same year. Central to the idea of the show were polychrome figurative sculptures of human bodies. The word “uncanny” refers to the Freudian concept of something that appears familiar and alien at the same time, stirring in the viewer strange feelings, as for instance when confronting a doppelganger or double. In his 2010 Gwangju Biennale, Massimiliano presented a non-authorized replica of “The Uncanny” as a tribute to Kelley — a tribute that was, however, unwelcome by the artist himself.

Is this Biennale ultimately a collector’s narrative? Is Massimiliano a collector himself who hides among artist’s collections? We know that collecting is an act of compulsion and that for a collector the most important piece is always the missing one…

To see photo albums dug up by Cindy Sherman from garage sales, which tell of anonymous suburban American lives, and to realize they have been the inspiration for one of the most iconic bodies of contemporary art, is without a doubt a unique and authentic experience for visitors to this year’s Biennale. In this same section of the exhibition we find strong, emotionally intense and highly representative works by Rosemarie Trockel. As I move on, my heart aches in front the silent beauty of Shinichi Sawada’s work, but I grow uneasy as I read the accompanying description on the wall: “Born with severe autism, Shinichi Sawada barely speaks…” Sanity and psychological equilibrium aren’t parameters with which I usually judge an artist’s work. There are many examples of works by acclaimed artists who have been afflicted by great psychic suffering and mental illness, but usually their labels do not read as such: “Afflicted by bipolar disorder for many years, lives under the constant effect of mood regulators,” or, “he/she has suffered from chronic depression since birth and throughout his/her life he/she has self-medicated with vodka and cocaine.”

From this moment on, starting from its center, the show begins to shed its scales. It becomes fragmented, regardless of the quality of the work exhibited. Mark Leckey’s video reinforces the curatorial position: that of using fragmented information and heightened consciousness to return to magic in a post-technological era.

In the show’s final section, Massimiliano pleads for the blessing of the fathers: Dieter Roth, Walter de Maria and Bruce Nauman. Unfortunately, resorting to this male genealogy is not enough. It’s not clear why these artists are here, except that they are unquestionably great; possibly because of this they are called upon to legitimize the situation… And so the exhibit slides toward its finale.

The other part of the show in the Padiglione Centrale dei Giardini includes three other great father figures. Here is The Red Book by Carl Jung, the grandfather of modern psychotherapy. After his death, Jung’s successors would try to hide this work. Jung began compiling data for this diary of the unconscious in 1913, the year he broke away from Freud, at a time when he feared he was teetering on the edge of madness. Leaving the magic circle of The Red Book, or Liber Novus as it was originally titled, we find ourselves in front of a cast of André Breton, the father of Surrealism, made by René Iché. A decade after Paul Klee, the Surrealists turned to madness as a means of freeing language from bourgeois conventions, logic and linear thinking. The movement helped re-evaluate the creative value of artistic expressions by the insane. Nothing is new here; and so it went during the rainy inaugural days of the 55th Biennale.

Later, it is time for Rudolf Steiner and his blackboards drawings. Founder of the Anthroposophical movement, Steiner was a prolific and inspiring lecturer who is said to have held all-inclusive conferences even for the milkman and the plumber who came to his house. I think of Joseph Beuys, who isn’t in the show. In the central garden pavilion are exceptional gems, like KP Brehmer’s skies and Aleister Crowley and Frieda Harris’s tarot cards. Pardon my leaps between styles and periods, but that is what occurs in Massimiliano’s palace, built upon his personal cosmology. Are we witnessing curatorial superpowers? Is Massimiliano a curator of exhibitions who would like to curate worlds? Isn’t this omnipotence the secret ambition of every curator? Let’s just rearrange the universe the way we like it, man. I begin to feel overwhelmed by all the material.

At the end of this tour of the 55th Venice Biennale, what I’m left with is the feeling you have after a sleepless night spent searching the Internet with dozens of web pages left open. We don’t even recall where we started. Such is knowledge in the age of the digital. It is the “Wikipedic palace,” after all. It is a greedy and bulimic show with blind spots and omissions. With its interesting but fragmented materials, the contents have somehow already been assimilated by the discourse of art.

Massimiliano Gioni’s Biennale is, beneath it all, a kind of nostalgic look back — yet played fast-forward and schizzed out like a character in a Ryan Trecartin video.