“Curator” is a pretty new word. It has made its way into dictionaries over the past few decades, and we only started talking about “curatorial studies” in the 1990s. But hey, we’re all about new methods and attitudes around here. For our new column focusing on experimental curatorial and editorial approaches to gallery culture, we played around with words. We present “The Curist.”

Two Queens, the artist-run gallery and studios in Leicester, occupies the increasingly rare role in contemporary art of a seasoned project space intended to serve as an incubator for artists to work through ideas free from market constraints.

In the twelve years since its establishment in 2011, the organization — run by Gino Attwood and Daniel Sean Kelly — has consistently delivered programming with a significant impact on the UK’s cultural landscape, presenting pivotal projects from artists including the likes of Joey Holder, Jala Wahid, Alice Theobald, R.I.P. Germain, Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings, Hannah Perry, and Jesse Darling, winner of the Turner Prize in 2023.

Amid the infrastructure of contemporary art giving way to the proliferation of a hybrid of project-space-meets-commercial-gallery, I spoke with Gino about the history of Two Queens and the complexities of sustaining an enclave dedicated to artistic experimentation.

Caroline Elbaor: How are you doing, Gino?

Gino Attwood: The caffeine is just kicking in. I’ve got this slightly unnecessary, overly complicated coffee brewing process, where I use digital scales and weigh and grind beans to make pour-over with a drip kettle.

CE: I had one of those where you have to drizzle water in a certain way, so the coffee looks like it’s blooming.

GA: The bloom is what it’s called; it’s the technical term. I know this because of YouTube.

CE: So I take it you’re one of those people who really likes YouTube tutorials?

GA: Definitely. It’s something that’s part of my curatorial or artistic existence: how I connect with the art world or whatever has always been very online.

CE: I figured the internet underlined your approach in some form, just based on the artists you show. It’s not overt, but it’s there.

GA:Completely. I graduated in 2011, at the tail end of post-internet art, so while I was at university, there was so much stuff.

CE: Yes, that would have been prime post-internet; 2006 at its height when we were powerless to escape it.

GA: And because I studied at Loughborough University in the East Midlands, the internet was how I engaged with the art world.

CE: That makes sense; you were isolated. I’m not disparaging the Midlands, but without the internet, it must have felt like, “Who else do I have to talk and relate with?” The sheep.

GA: When we started Two Queens in 2011, Leicester had no big institutions. There was a small space called City Gallery that lost its foothold when it was absorbed into the City Museum, but even only a small percentage of exhibitions there were actually looking at contemporary artists, and the ones they did show were already established, like Cory Arcangel.

CE: Yeah, basically the UK’s darling.

GB: Exactly. Adding to the lack of support for a major visual arts venue, very Leicester-specific lore around King Richard III also changed the city at that time. He was the last king of England to die in battle, and local legend said his body was thrown into the Soar, Leicester’s river, but it turned out he was buried in a modest grave under an old little chapel, which was knocked down and paved over. They eventually found his bones under a car park in 2012.

CE: Are you serious? That is crazy. The car park especially feels like some kind of contemporary commentary.

GB: Growing up, I had a very clear image in my mind of Leicester. We were always told it was multicultural and pluralistic, and its high concentration of people from other countries was celebrated. It felt weird when this medieval history got folded in: Leicester is now a city of heritage, tourism, and violence. It left a bad taste in my mouth. It also meant that all the money went into heritage, which felt sad because we still didn’t have any substantial cultural investment in what is going on today, and that was part of forming our responsibilities for Two Queens.

CE: Where did the name come from?

GB: Literally our address. We got really lucky with the building because it was a big space that had just been lying empty after the 2008 financial crash. We came in on the back of a failed city cultural regeneration project, so we’ve always joked that the gentrification had failed, and we moved in and did it the other way around. The beginning was intense. We took turns alternating two sets of shows, which became an exhibition program.

CE: Where were you getting funding from?

GA: Nowhere. That first year was completely unfunded and very DIY. We paid for a van to drive to London and pick up works for weird little collaborative projects. We only had a three-month rolling contract, so we didn’t think we’d have the space for long. All the walls we built were just bolted together, thinking we’d probably have to move, and many of those walls are still there twelve years later. It was pretty ramshackle, full of shit, and always felt a bit tenuous. I had guilt about the amount of unpaid labor.

CE: The thing is that unpaid labor is the story of art. It’s the sentiment of the union adage that you can’t eat prestige.

GA: Totally. We’re always trying to figure out how to improve how we pay artists. One tactic is paying them more to do less, which has been difficult for us to absorb, but the expectation that the artist isn’t the least well-paid person should be the norm.

Our most significant projects have been quite intense new commissions, like R.I.P. Germain or Joey Holder, so huge amounts of work for artists to produce and us to realize. As an organization with limited resource capacity, we must find a balance to keep those shows where artists push themselves at our core.

Another example is Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings’s show. I initially thought it’d be drawing and painting, but they’d just finished their UK gay bar directory and were keen to make a film. That project was down to the wire because it was their first time working in full-scale video production.

That’s when I realized the importance of supporting artists doing that kind of work, where they’re pushing ambition and scale. Because our space is very big, and many people can get stressed by a show in it.

CE:Cavernous spaces can be like a riddle. Dallas Contemporary, for example, was originally a manufacturing plant, so when putting on exhibitions, there was a constant question of how the work would do best in a sprawling and stark warehouse. Its vastness stressed me out, but like you’re saying, when an artist is up for engaging that stress, what they produce often ends up lending itself to the space and vice versa.

GA: Yes, 100%. The size of our space feels like a room in an institution in some ways, and I think when artists can show that they can make work on that scale, they’re more appealing to institutions.

CE: Playing Cupid a bit, as if you know institutional curators won’t be able to resist once they see the work in those circumstances for themselves.

GA: Yes, Hannah and Rosie’s film then went into the show at Hayward Gallery, “Kiss My Genders,” in 2019. Something clicked for me at that point, and I thought, “Oh , shit, we can help artists in this way, we can be of more value to them.” So, rather than scale back, we want to help artists push themselves.

CE: Yes, that can help the longevity to their careers. Not to mention, pushing themselves is just a good thing to do in itself.

GA: Yes. We try to explain to artists that Two Queens is where you can test things and experiment, meaning literally, not just as an art practice that seems “experimental” because it’s not traditional. Our space can hopefully be experimental in the context of their own practice, where they can try and develop a new kind of work or working process. For Hannah and Rosie, it was making a film, and they also went on to make another.

CE: It gives them a sort of freedom.

GB: Yes, and in a place where it’s maybe safer. It’s not the same feeling as having a show in London, where the scrutiny is different. Although Leicester is only an hour from London, hopefully, what people are allowed to do here is more than what they do when there’s pressure to sell.

CE: I struggle with the commercial gallery structure because I feel like quality risks falling by the wayside. Showing bankable work is their basic business; that metric could clip artistic development in the form of experimentation you’re talking about. I mean, even a successful artist might be stifled under this model because the gallery could have no monetary impetus to encourage experimentation with anything new. I get that commercial galleries are intrinsic to the art world ecosystem, but the principles you describe with Two Queens are why I didn’t want to work commercially.

GA: Definitely. I think that’s where I’m most like an artist: someone who has an art practice and wants to make as much art as possible and work with artists as much as possible. That’s why I’m still excited about Two Queens because it feels like you’re encountering the work at this stage, where it’s still forming.

We’re also trying to supplement our program by paying people to show work they’ve already made, so we’re not burning out while living on these fractional, precarious employment contracts. I think I realized not every exhibition has to be nearly killing us, with 3 a.m. installs every night.

CE: Sometimes I get weirdly high off all-consuming, 3 a.m. nightly install periods, but that shouldn’t be the baseline.

GA: R.I.P. Germain’s show, “Shimmer” (2022), where we built the newsagents in the gallery, felt a bit like the early days when we didn’t know what we were doing because instead of gallery walls, we were building something specific with a different kind of architecture, including ceiling tiles and security locks.

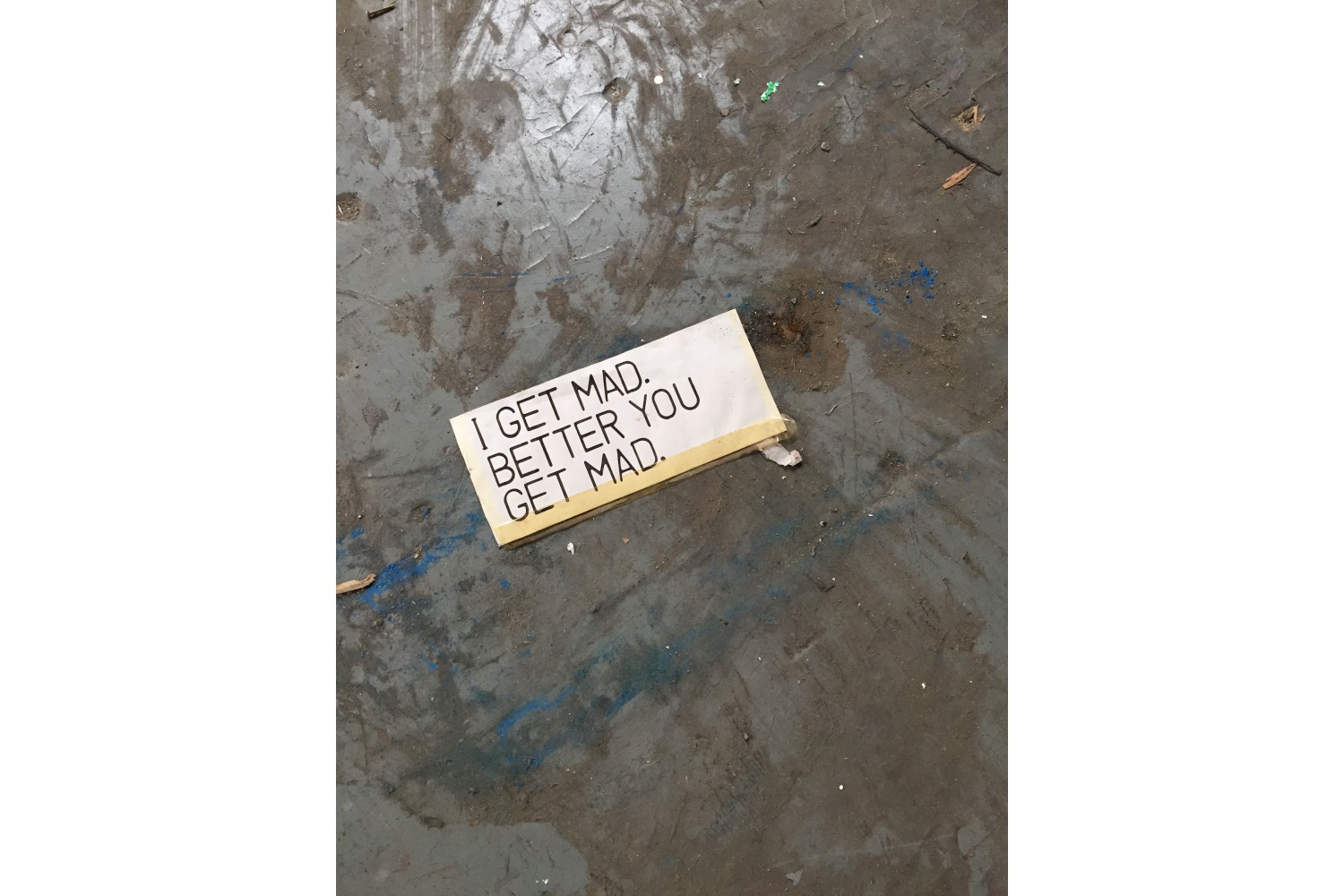

The show was about access to spaces and what we might not realize goes on in certain spaces behind the scenes, and it had a gamified element to it, where you had to solve things to get to the back room. The first door you encountered said “Staff Only,” but of course, you could just walk through it. The second door had this futuristic digital key code to enter the final chamber.

CE: “Chamber,” that is very video game-y of you.

GA: Yes, it was like getting closer to the end boss or something. It almost functioned like a boss because you were interacting with this fictionalized character of someone the artist met in real life, and if you interacted the wrong way, you were sent straight back to the beginning. It was a fun exhibition to engage in with people because there’s so much autobiographical narrative within R.I.P.’s work that it can feel quite conversational.

Sometimes I want to be able to look at the work we do at Two Queens fresh without knowing how it’s been made. That is often a feeling that I get with shows. I would have loved walking in on this without having climbed out from the inside.