Thirty years ago, Dan Graham proposed a plan for a movie theater that would immediately lay bare cinema’s social and psychological structures. Cinema (1981) is an architectural model for a corner theater with a façade of two-way mirrors between the film audience and the passers-by on the street. Depending on which side has more light, viewers can see what is happening in the other space. In reference to psychoanalytical film theory, the conventional screen is substituted by another two-way mirror. Once a film ends and the house lights go on, the movie viewers become fully visible to the outside spectators as well as to themselves in their own reflections on the mirror screen. Graham’s experimental set-up illuminates at a glance what is fundamental to cinema from the very beginning: its status as a mass medium that addresses a group of people gathered in one space. In comparison, Graham’s Public Space/Two Audiences (1976) condenses the position of the viewer in the museum. Similar to Cinema, the artist alters the existing architecture of the exhibition space with mirrors and glass and takes away the usual object of the gaze, in this case the art object. What is left is the spectator confronted with the image of herself/himself looking at herself/himself.

Against the backdrop of these two radically different viewer positions, a recent tendency of visual artists to venture from the white cube to the black-box movie theater is noteworthy. Over the last five years, artists such as Shirin Neshat (Women Without Men, 2009), Steve McQueen (Hunger, 2008), Sam Taylor Wood (Nowhere Boy, 2009) and Pippilotti Rist (Pepperminta, 2009) — to name only a few — temporarily left their accustomed gallery settings to create feature films with methods of production and channels of distribution more common to the world of art-house cinema. Most of the films went through the international film festival circuit and were widely released. One reason for this surge of feature films made by artists was surely the now-burst art market bubble, which heightened backer’s willingness to invest in costly productions. Another was the desire to reach an audience outside the art world. As Pippilotti Rist writes in the film distributor’s brochure for Pepperminta, “The ritual of consenting to sit together for a specific length of time in the dark room lends cinema a very special strength: the viewers sit together in one and the same thought bubble!” This wish to connect with a mass audience through cinema comes somewhat as a surprise at a time when the old system of film distribution and exhibition yields to the Internet, a meta-distributor that can deliver any form of moving images right into people’s homes.

Cinema’s ability to speak to the masses was already acknowledged in early Soviet and German film theory. Because of the loss of aura through mechanical reproduction and the collapse between individual and collective perception, Walter Benjamin asserted the possibility of turning cinema into a revolutionary art form, a naïve belief that was harshly criticized by his colleagues from the Frankfurt School and proven painfully wrong by the Nazi’s propaganda machine and Hollywood’s total commercialization of film. Most of the time, truly experimental and avant-garde cinema had to be produced outside the mainstream with independent means and was usually shown away from the masses in small theaters or outside venues during the Expanded Cinema movement of the ’60s and ’70s.

In the early ’90s, the marginalization of experimental cinema took a new turn when a generation of visual artists started experimenting with the language of classic cinema and projecting their results in art galleries instead of alternative theaters. Artists like Tacita Dean, Douglas Gordon, Stan Douglas and Steve McQueen appropriated the by then almost 100-year-old canon of cinema, and their works entered the collections and exhibitions of major museums, a product of more affordable and flexible projection technology, but also of the new generation’s nostalgic view of a vanishing medium, replacing the negative attitude of the preceding generation of underground film makers. Large seductive projections in dark empty spaces became a familiar sight in art exhibitions and biennials.

In the gallery spaces, cinema was presented to individual spectators as a one-on-one experience instead of as a communal one. Art exhibition visitors brought with them a heightened willingness to watch abstract, non-linear and fragmented moving-image art works. Their ability to move unrestrictedly around the screens, to walk in and out of presentations at any given time, seemed to be a new freedom compared to the fixed position of the cinemagoer. However, Dan Graham’s Public Space/Two Audiences makes apparent that the visual regime of the art gallery is as ideologically charged as the tiers of a movie theater. With their entry into the white box, cinematic images became a continuation of a visual structure that has been concerned with the creation of the individual subject starting with the 19th century. In this genealogy, art exhibitions constitute a public ritual that explicitly addresses the individual who understands himself/herself first and foremost as such, and therefore makes for the ideal subject in capitalist consumer society.

Artists have been attracted to making films throughout the medium’s history, playing an important role in the discovery of film’s aesthetic possibilities. An early film work by the painter Fernand Léger (Ballet mécanique, 1924) playfully explores its abstract potential, quite similar to the Dadaistic experiments by Man Ray (Le rétour à la raison, 1923, and Emak-Bakia, 1926) who later worked with Marcel Duchamp on challenging viewing and reading habits with the kinetic film installation Anémic Cinéma (1926). In a surrealist manner, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel (Un chien andalou, 1929), as well as Jean Cocteau (La Sang d’un poète, 1930), explored film’s marvelous effects of jump cuts and superimpostions.

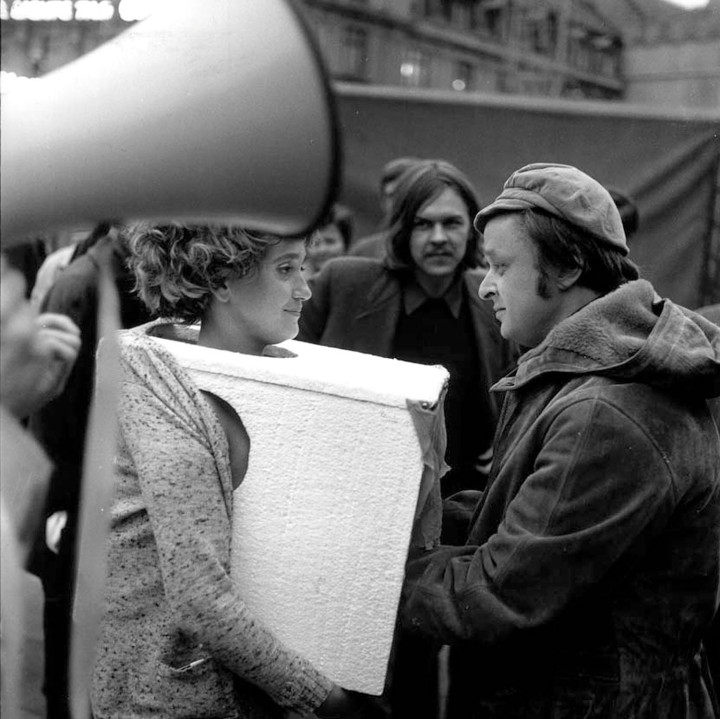

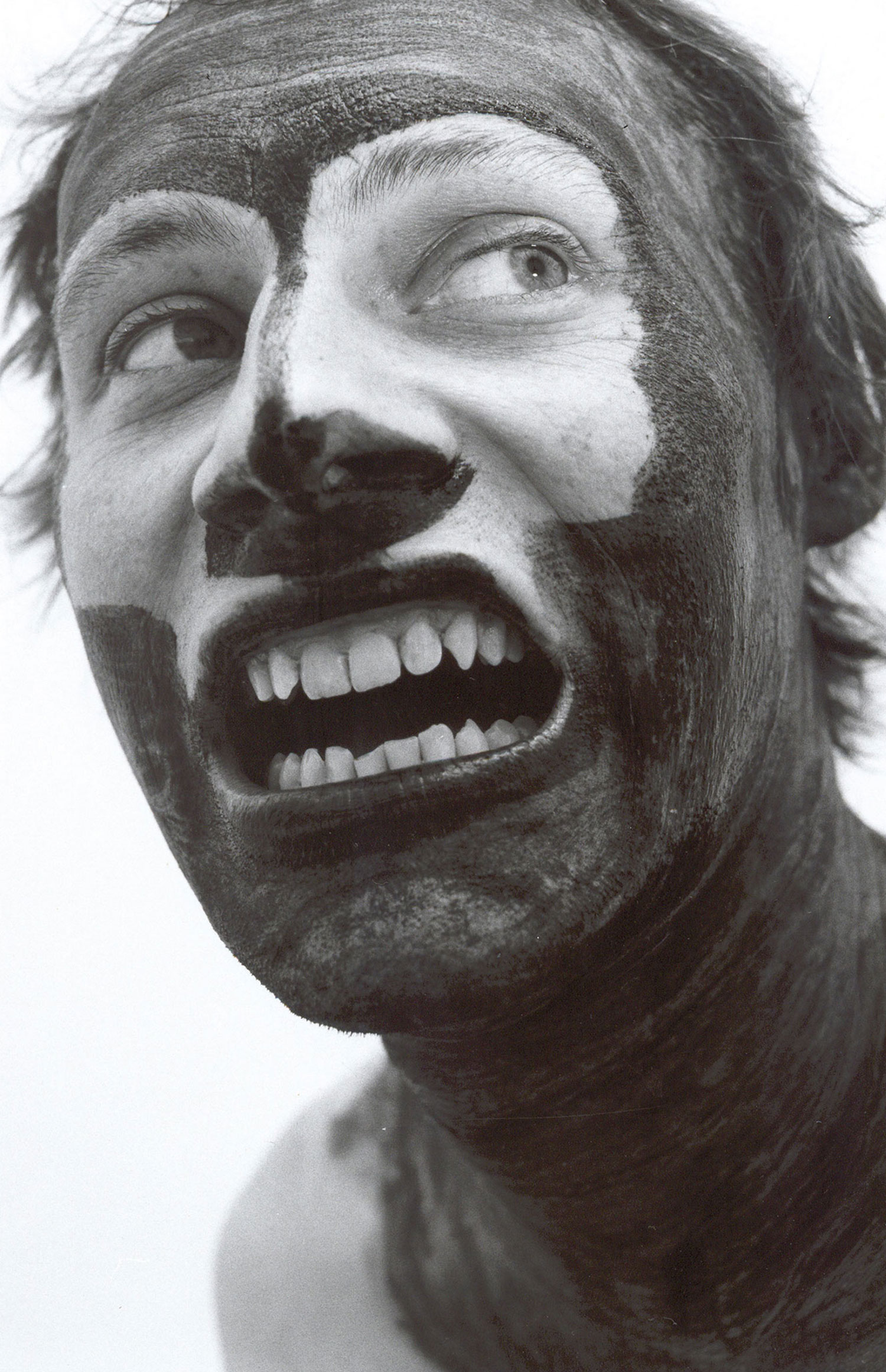

After WWII, the distinctions between painting, literature, dance and film blurred even further. Many artists sought proximity to underground film, which advocated the representation of sexually explicit and politically pressing material. In Fuses (1967), Carolee Schneemann shows coitus from an impressionistic female perspective whereas VALIE EXPORT challenges cinema’s patriarchic gaze with her provocative actions such as Action Pants: Genital Panic (1969) and TAPP und TastKino (1968-71), for which she encouraged people on the street to touch her breast through a portable and curtained contraption. With over sixty films — excluding the screen tests — Andy Warhol is the artist who pushed the crossover between art and cinema to its most extreme. Even though his films were always independently produced and, apart from Chelsea Girls (1966), never widely released, Warhol’s promotion of Superstars, and his later interest in magazines and TV programs, attest to an obvious lust for mainstream relevance.

This lust would carry over to Warhol’s successors, the so-called Pictures Generation artists, who proved to be extremely media savvy, treating popular culture as a never-ending source for their artistic endeavors. The incorporation of visual vernacular lent critical depth and cultural relevance to their art. However, their ambitions to produce films with mass appeal fell artistically and commercially flat. Neither critics nor audiences ever got excited about Robert Longo’s highly produced cyberpunk film Johnny Mnemonic (1995) starring Keanu Reeves. And David Salle’s star-studded Search and Destroy (1995) is, at best, visually striking, never exceeding its disposition as an empty cynic satire. Similarly, Cindy Sherman’s horror melodrama Office Killer (1997) does not really hit the spot as it is seemingly supposed to. The only exception among the artists that emerged in the ’80s is Julian Schnabel (Basquiat, 1996; Before Night Falls, 2000; The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, 2007; Miral, 2010), who might be remembered more for his films than for his paintings one day. The Pictures Generation marks a turning point in the historical flirt between art and cinema inasmuch as it seems to have had an interest in neither extending the medium’s boundaries nor looking for new cinematic ideas in a Deleuzian sense. Since then, artists have chosen to work with moving-image installations rather than movie theater screens in order to create alternative ways of thinking and make visible the role of time and space in it. One of the few exceptions is Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s soccer film Zidane: A 21st-century Portrait (2006), which has a structural temporality that defies any ideas of sport coverage or film portraiture and is a powerful testament to the immeasurabilty of life. Comparably, but with diametrically opposed means, Matthew Barney’s excessive Cremaster Cycle (1995-2002) transcends cinema by being intrinsically tied to the artist’s sculptural practice. It is noteworthy that both film works also exist as gallery installations in which their multilayered temporal and respectively spatial dimensions become more palpable.

Next to these examples, the latest wave of artists-turned-filmmakers is rather disappointing. Employing strong cinematic language and leaning heavily on good writing, Steven McQueen’s Hunger (2008), a film about the last six weeks of the life of the Irish republican hunger striker Bobby Sands, is probably its most successful outcome. Apart from a few scenes and the self-conscious use of sound that attest to the artist’s interest in structural foundations of the medium, the film does nothing to advance the art form itself. Most of the other artists, like Pippilotti Rist, simply take ideas they have been successfully developing for their gallery works and stretch them into feature length films, adding some dialogue and narrative elements to the mix. Shirin Neshat’s Women Without Men is the most irritating example in the group because it attempts to be political as well as emotional without ever breaking through the cliché-like character of breathtakingly beautiful and highly seductive images. If the only thing we should expect from visual artists is their offering us alternatives to the relentless bombardment of empty, numbing images in media society, Piotr Uklański, too, fails with his Polish version of a Spaghetti Western called Summer Love (2006). The film — starring Val Kilmer and catering to art-film audiences — tries to overcome the cliché by taking it to its most extreme but instead gets caught in the self-referential deadlock that is irony.

Dan Graham’s plan for Cinema has never been realized. It only exists in the form of an architectural mock-up. Nevertheless, it has proven to be a productive thought model for reflecting cinema’s nature, its structure and its possibilities. By stressing the importance of the border between inside and outside, the model demonstrates why artists are doomed to fail when they swap the modes of production and distribution from the art gallery to the movie industry without reflection: they simply end up with a different set of ideological confinements. Consequentially, the most interesting work right now is being created in the spaces that operate between art and cinema.

Pretty much from the beginning of his career, Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul has worked simultaneously in exhibition spaces and movie theaters. His recent multiplatform project Primitive (2009), consisting of interrelated installations, an artist book and two short films, has traveled to different art institutions in Munich, Liverpool and Paris. In one of Apichatpong’s short films, a movie screen is burned down by a group of Thai teenagers revealing a ghostlike projector beam. The German artist Clemens von Wedemeyer shows a similar interest in the screen as a threshold between inside and outside that needs to be reconsidered. For a project in the small town of Mardin, close to Turkey’s southern border with Syria, he is currently building a sculptural open-air cinema in one of the few public spaces. On its backside, the big monolith screen will be — in reference to Graham’s model — covered with mirror glass reflecting the sun while it sets in the east. Once Sun Cinema (2010) is completed, the people of Mardin, who have been living without a functioning movie theater since the civil war between the Kurdish PKK and the Turkish army in the ’80s, will do their own programming, supporting von Wedemeyer’s case for reviving cinema’s communal and ritualistic values.