According to many renowned local contemporary artists, Eastern Europe appears to be a rust zone filled with paint-striped concrete blocs, a steel gray sky and unwilling staffages. This inconsolable image is underpinned by the machine-precise documentary work of young photographers working in the footsteps of the German Becher School.

To this group belongs the fine art photographer Tamás Dezső, a former photojournalist. With a style that is at once restrained and monumental in its serial approach, he is an heir to the socio-graphically concerned novelists of early 20th-century Hungary. His series entitled “Here, Anywhere” (2009-2011) documents disillusioning post-socialist moments: a downtrodden character clutching a special breed of Hungarian pig in front of a barely plastered wall (Peter with a Mangalitsa Piglet, 2009); a stark bus stop on the outskirts of the foggy Hungarian plains (Bus Stop, 2011); and a car wreck abandoned near a derelict suburban social housing estate (Car Wreck, 2009). During communism, this type of photo and film documentation was considered dangerously confrontational to state-sanctioned propaganda.

The work of Dezső, who, as a descendant of the liberal, pro-opposition documentary style of the ’70s, today attracts not censorship but Western audiences for its time-capsule characteristics. For local viewers these images often seem atypical and uncomfortable; for foreigners they are engaging. After all, Eastern Europe is a kind of Bikini Atoll to the Western world, where the atomic experiments of communism were conducted and, a few decades later, horrified by the destruction and deformed contamination of ideologies, were terminated. Tamás Dezső searches for manifestations of this epoch of “explosions,” interpreting found content as bitter, universal metaphors for contemporary life. The official art of the Soviet epoch presented the opposite of the Bikini Atoll.

The name of the Paris-based contemporary artist-duo Société Réaliste is a reference to this Stalinist stylization. Founded by the Hungarian-born Ferenc Gróf and the French native Jean-Baptiste Naudy, the collective is inspired by varied scientific practices, molding found stories in to a genre of “scientific essay.”They marry political design and experimental economics with architecture, typography and cartography, which is then presented with scintillating irony and expert graphic application. Their Parisian attitude suggests that it is more important to understand the heritage of the revolution than to enunciate the problems of the post-socialist era. In one of their early exhibitions organized by Budapest’s Trafó Galéria (“Transitioners,” 2006), they compared the characteristics of Western-funded democratic evolutions (e.g., the Ukraine’s orange revolution) with the latest fashion styles predicted by Trend Union, a trend-forecasting organization.

From this they created “Transitioners,” an unprecedented stylist studio committed to exploring political changes with a design consciousness. They returned to the basics: to the heroes and color scheme of the French Revolution. Historical figures, from Robespierre to Marie Antoinette, were allocated a unique color code determined by the individual’s characteristics and allocated according to a scientific graphic scale based on the CMYK color scheme. At a recent exhibition (“Xenolalia,” 2010), the Communist Manifesto in English was sketched on the walls of the Kisterem Gallery with a pencil; each word was replaced with its conceptual anonym. This double-edged manifesto, where transposed Marxist phrases looked out of place in English, was presented on a map of Europe. Their interest in the revolutionary spirit continues with Subject to Change: Orange (2011), which is a medium-sized enamel plate with a familiar image.

This vision of the athletic worker with hammer in hand was conceived in 1917 by the Hungarian graphic designer Mihály Bíró as the logo of the left-wing worker’s broadsheet Népszava. By 1919 it became the poster image of the Hungarian Commune in the form of large-scale transparencies and as decoration in public spaces.After World War Two, the man with hammer reappeared as the eternal icon of the empowered worker. Société Réaliste poignantly re-appropriates the third digit of the 1919 edition as a question mark that signals the cyclical nature of events by referring at once to the Commune, the 1949 Stalinist constitution and to the political changes of 1989. The orange color of the otherwise multi-shaded working hero also symbolizes the current Hungarian government’s struggle for power.*

Société Réaliste’s recent work addresses issues of contemporary Hungary with an enamel road sign bearing the name of a town cancelled out by a red cross (Sztálinváros, 2011). The sign is presented in an archaic Transylvanian font, which is increasingly popular among Hungary’s nationalistic and neo-pagan mayors. There is of course a signature twist to the work, as the place it refers to was a former new town built along the Danube River called Sztálinváros (“Stalin-city”), and has since been renamed as Dunaújváros (“Danube-new-town”).

In this artificial socialist industrial town lives Gyula Várnai, an autodidactic master of ingenious philosophical and conceptual works. One of Várnai’s recent works addresses the settlement’s political past. Neon Peace (2008) is a large-scale propaganda sign with the Hungarian text “Békét a Világnak!” [Peace to the World!] written on its base, with a dove grasping a palm tree branch in its beak depicted above. The vision of the dove, invented by Picasso in 1949, cunningly aligns the European tradition of humanism with left-wing internationalism.

The image recalls its omnipresent reproduction during socialism, which graced Sztálinváros on the top of its highest architectural point: the “socialist-realist” (more commonly known as “soc-real”) pharmacy building. This neon light, considered a key directional point of the city at night and an indication of the city’s metropolitan ambitions, was eventually removed in the 1990s. In 2008, Várnai presented a smaller version of the work as a public art project in a grass strip positioned across from its original location. The neon peace dove has since graced the monumental red marble walls of the Hungarian National Gallery, once the home of the Workers’ Movement Museum, as a warning to the vacation of political symbols and their lurking messages (“The New Refutation Of Time: Works from the Irokéz Collection,” 2008-2009).

Isolated by the Iron Curtain, Eastern Europe conducted not only the experimental explosions of communism, but also explored the varied possibilities of modernism, which, in contrast to the capitalist program of the West, was initiated by its social engineers. Hungarian artists have of course explored many alternate chapters of the nation’s bloody history, from the Hungarian Conquest to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. And yet, Western audiences remain most interested in local interpretations of what is at best understood as the latter’s own progressive-modernist roots. With its unknowingly familiar “orientalist” appearance and fused symbolism, in Hungary this is known as the “soc-modern.” This reading is made available, of course, only if we examine the gray tones of the Cold War’s black-and-white color scheme. As one example, the Hungarian communist leaders convinced renowned avant-garde émigrés to return home. Op Art’s visionary founder, the Hungarian-born Victor Vasarely, received a dedicated museum, and his enamel plaques made regular appearances in public spaces.

Raised in an era of non-figuration and with an indoctrinated optimism, Hungarian art of the 1960s received a great blow. This could be said for the official art’s neutral decorative characteristics, and also for the unofficial arts movement. While there were fundamental differences between the two, the troubled avant-garde graphic artist János Major protested against the monstrous 1969 Vasarely show in Budapest with a piece of paper declaring “Vasarely Go Home.” This was a standard blockbuster show that the government staged to legitimize its international standing while at the same time persecuting the local avant-garde. Andreas Fogarasi, a Viennese-born artist of Hungarian roots, commemorated this incident in his recent exhibition at Madrid’s Reina Sofia. He presented documentary photographs of the event on freestanding marble slabs and video news footage about Hungary’s arts community at the time of the incident (Vasarely Go Home, 2011).

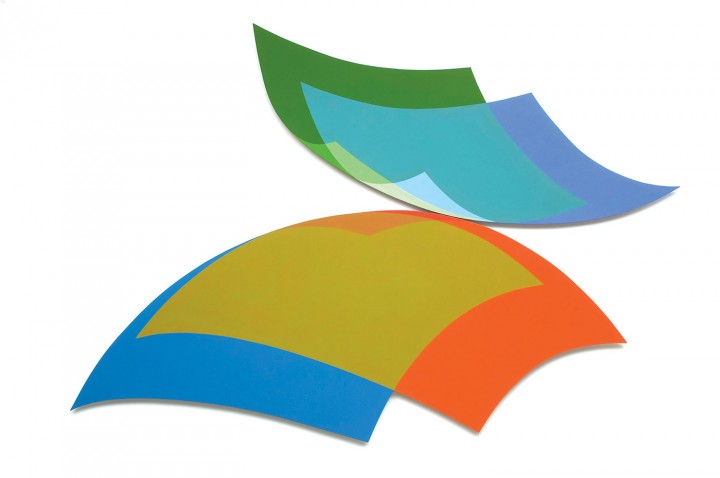

There were many Hungarian followers of geometric abstraction, hard-edge painting and concrete art during the progressive years of the ’60s. From this climate emerged Dóra Maurer, who initially focused on conceptual photo-analysis before turning to consequential geometry. After the political changes of the ’90s, Maurer, like many of her contemporaries, took a teaching post at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest. As a consequence, she educated younger and younger generations with a late-modernist geometric language. To this group belongs Ádám Kokesch, one of her most outstanding students. Kokesch emerged on the local arts scene a decade ago with a distinct style of non-figurative signs and suction-cup objects mounted on plexi sheets. Kokesch paints these seemingly unidentifiable symbols on walls, windows and corners; at times they appear as molecular formulae and monoscopic color schemes — relics of an unknown civilization or futurist visions of our own visual culture.

Victor Vasarely attempted to design the planetary folklore of a galactic society, while Kokesch continually examines the shattered ideals of modernism through his inanimate objects for which he creates environments using industrial suction-cups, plastic stands, neon tubes and metal props. Yet Kokesch no longer believes in the power of natural scientific art; his geometric patterns are drawn without a ruler, constructed by eye; the sterile laboratorial setting is at best considered as a stage set. His untitled works commemorate the aesthetic decorum of late modernism like an empty snail shell, reflecting with regret on the abandoned context of his mission. At the underground venue of his last show (“Platform,” 2012), the floor was covered with white sticky-tape, presenting a sterile stage for the potted plants to extract the seeping poison from the air. Could this be anything but the desperate clean up of a Bikini Atoll explosion?

Another Hungarian visual artist, Ádám Albert, examines these late modernist clichés from a typographical perspective. At first Albert created fictional enamel taxonomy plaques for botanical gardens, and later he exhibited large-format urban guerrilla signs on public wall surfaces. Made from MDF discs, his “Decoder” series (2008) reproduced the modernist visual culture of the ’60 and ’70s in the shape of a large radio, a pin-legged clock, a cupboard and an archaic desktop computer. Painted white with minute details, the objects are finished with laser-cut logos (“decoders”) written in the stylized handwritten font of designer Battista “Pinin” Farina, whose work, despite the Cold War polemic, became the preferred font of many car manufacturers in both the East and West. Thanks to the Hungarian-made Ikarus bus, which became prolific in Eastern Europe, the font became a ubiquitous symbol of the ’50s and ’60s. Ádám Albert’s decoder boxes, despite the appearance of mechanical buttons, do not function. Instead, the sculptures appear attractive yet remain mute, just like the formalist doctrine of late modernism. And so it appears that in a local context, modernism has broken down. As these “Eastern” objects remain incompatible with “Western” ideas, soc-modernism can thus be interpreted from a contemporary perspective more as a bundle of failures than as a tale of success.

Albert’s decoders and Kokesch’s objects address the same ambitious art historical question: Is it possible to consider modernist works from the “irradiated” Eastern Europe as art at all? During the early years of socialism, strict rules ensued. After the 1956 Revolution the new party leader, János Kádár, expressed less stringent aesthetic views: “I am first and foremost concerned that they [the artists] serve the purpose of socialism in their varied styles. I couldn’t care less whether it is expressed as a six-edged head or with harmony…”

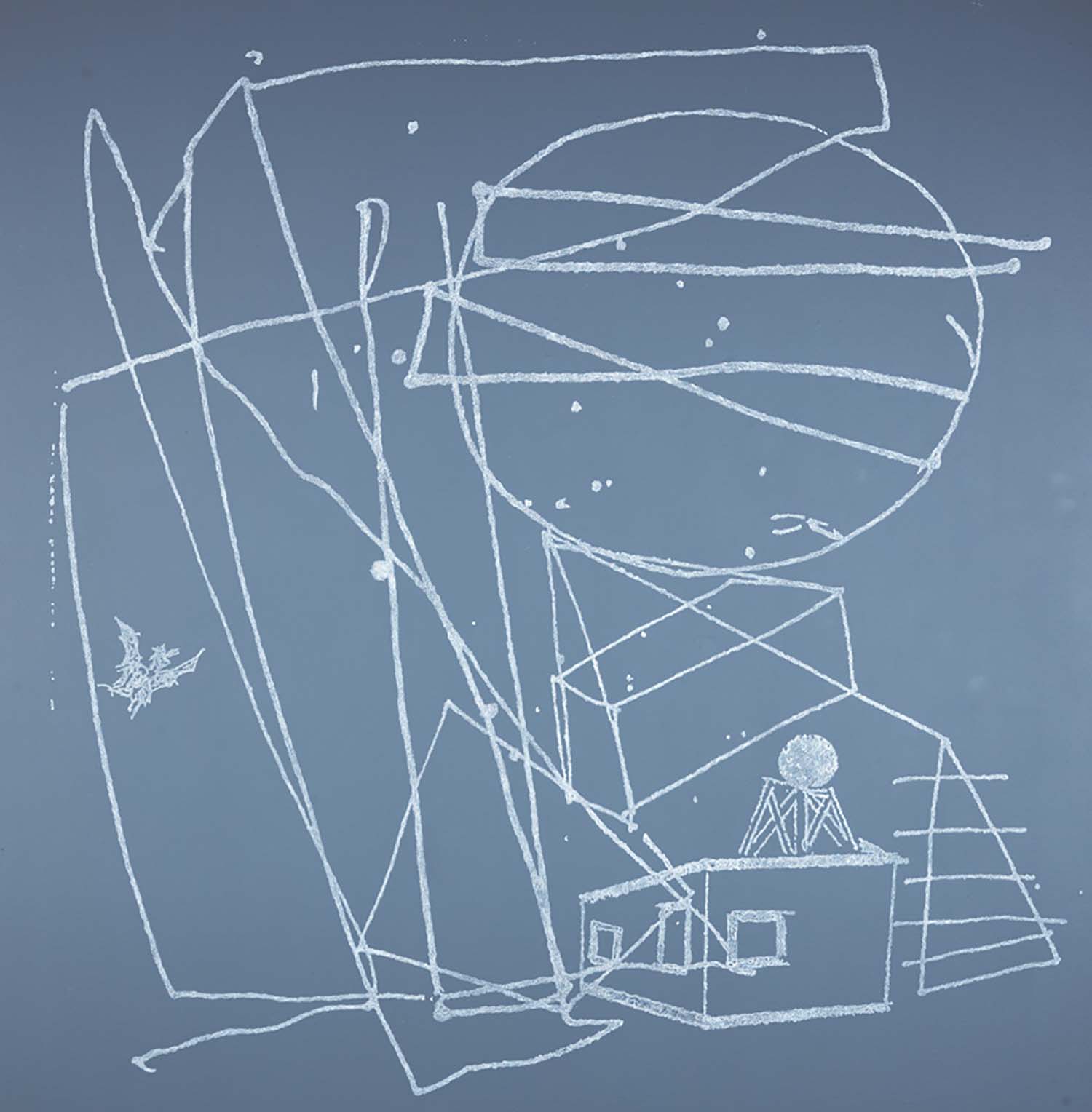

Soc-modernism was accepted as the synthesis of traditional avant-garde formalism and the socialist doctrine. Straightforward abstraction, however, remained banned. At best it was permitted for émigrés and for decorative purposes. Soviet satirical journals happily made fun of such non-figurative images, depicting an artist at work during a headstand, along with a monkey posing as an artist of an abstract-expressionist painting with an awe-struck audience of fat bankers.The Hungarian comic journal Ludas Matyi followed a similar narrative. One caricature presented an art historian trying to make sense of abstract brush strokes; on another, someone’s wife became a bundle of lines; and on a third, a blatantly well-dressed “Western” woman is enthralled by an abstract painting. In the center of all three images appeared abstract two-tone artworks. Painting an allusion to Kandinsky’s lyrical calligraphies and Malevich’s red-and-black squares, the images represented the sad state of affairs for Hungarian contemporary art at that time.

From these satires, Gábor Gerhes (b. 1962) — a conceptual artist working across media — painted a recent body of works. A five-piece series entitled “Every Image is an Enemy” (2011) and recently exhibited at the acb Gallery in Budapest is a critique about the cunning mechanics of power and the image-phobia of the Marxists. At the same time, it stands as an unrealized memory of a Western-style modernism that in Hungary only existed as the state-sanctioned soc-modern, and, in its absence, commemorated the ill-fated avant-garde. It is impossible to repaint every unrealized abstract image; and while history is a given and we can lament upon it, the ultimate task is to continue this path.