Caterina Barbieri is an Italian musician and composer. She completed her studies at the Conservatory of Bologna and then at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Her compositions are delicate interweavings of nonconventional rhythmic patterns and melodies. They explore the extremes of the listening experience, so that it becomes a flight over a precipice, or an exploration of the motionless chill of space. Her two LPs, Patterns of Consciousness and Ecstatic Computation — the former released in 2017 by Important Records and the latter in 2019 by Editions Mego — attracted the attention of specialist critics and the international public, confirming Barbieri’s reputation as a key figure in contemporary electronic music.

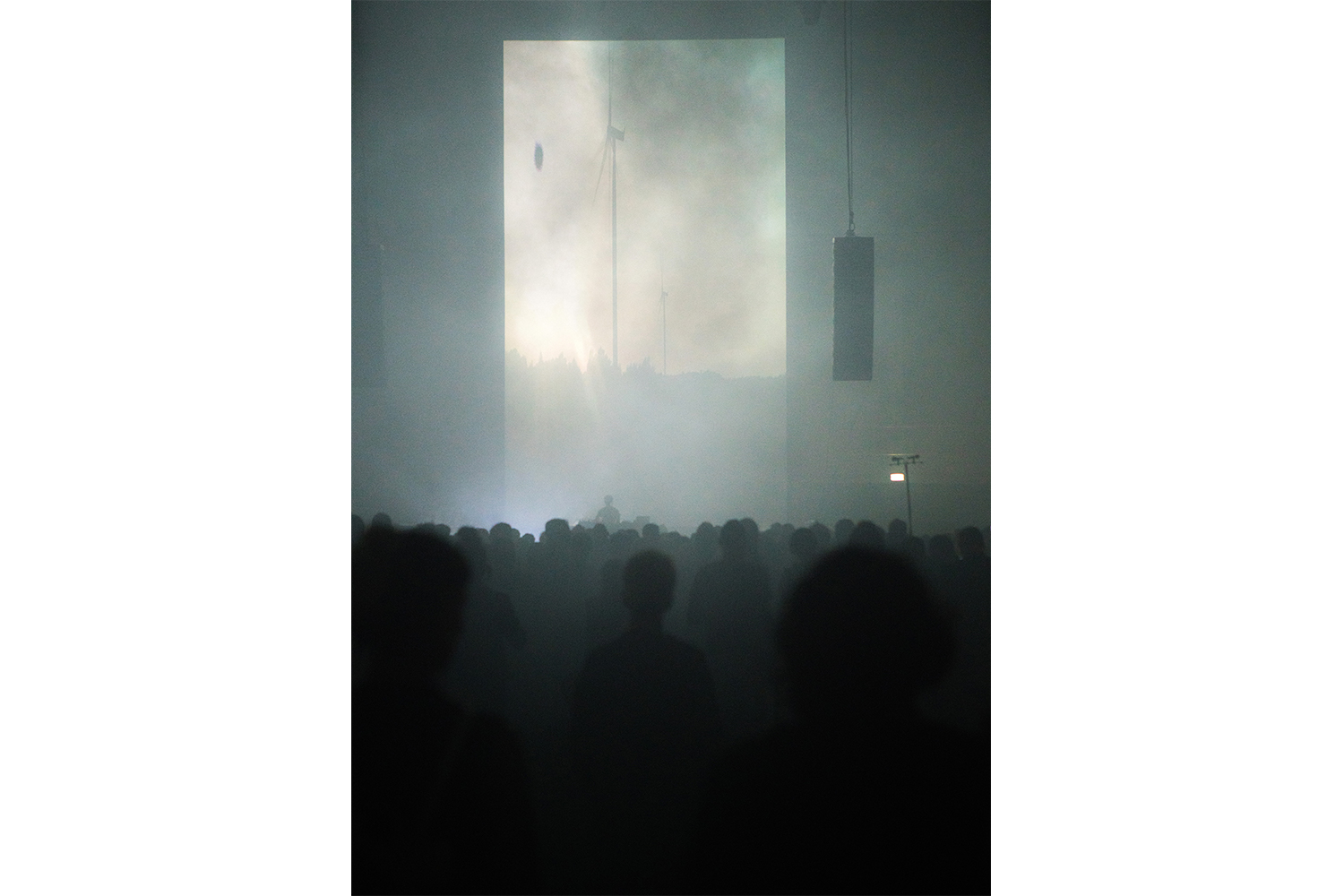

For some years, together with Caterina, I have been dealing with the visual dimension of her work. Our first collaboration was in Berlin in August 2018, when we presented Time-Blind, an audiovisual show produced by the Berlin Atonal festival that subsequently evolved on dozens of international stages, including those of the Unsound festival in Krakow, Sónar in Barcelona, Triennale Milano, and Club to Club in Italy. The conversation that follows is a extension of a dialogue between us that has continued over the years, punctuated by shared projects and research, in which two faithful rhythms accompanied and supported each other: the more insistent ticking of online communication; and a louder tolling when we expanded our discussions in person, in the wings, behind the LED walls of festivals, in the waiting rooms of hotels, or in airplanes at an altitude of eight thousand meters.

Shortly after Caterina moved to Milan, the COVID-19 pandemic paralyzed the public dimension of our profession. And so, in a certain sense, the digital space within which our collaboration first germinated and blossomed has now become another of the many bell jars where everyone’s relationships have been put on hold. We have become flowers standing side by side, but certainly not in a garden. Traditional interviews often refer to the connection between artists and their studios, that microcosm of objects that represent the visible signs of a creative sensibility. But there are no props on the stage in online communication. Phantom limb syndrome is a perceptible and painful absence. For a year this void has become the only location for most of our relations, and in acknowledgement of this experience, which is by now collective, I refuse to garner my memories to conjure up the room where Caterina composes. Instead I prefer to carry out this conversation in the dark, trying to map out the void together with her.

What does this abyss conceal? Perhaps, if we keep our eyes open and wait long enough, we will recognize an unexpected presence in the darkness. I am thinking of the “Dirac sea,”1 an obsolete theoretical model of the vacuum as an infinite sea of antimatter that postulated the existence of particles, which were then discovered experimentally. Neptune was also discovered “in the dark,” due to the gravitational force that it exerted on the other planets, as the moon does with the tides on Earth.2 Or the arctic expeditions that set up their tents on floating icebergs and let themselves be borne adrift toward the pole, traveling through the unknown areas that cartographers call “sleeping beauties.”3 In her music Caterina explores the blind spots and open wounds of our perception, and that is why I wanted to face the darkness of the present with her.

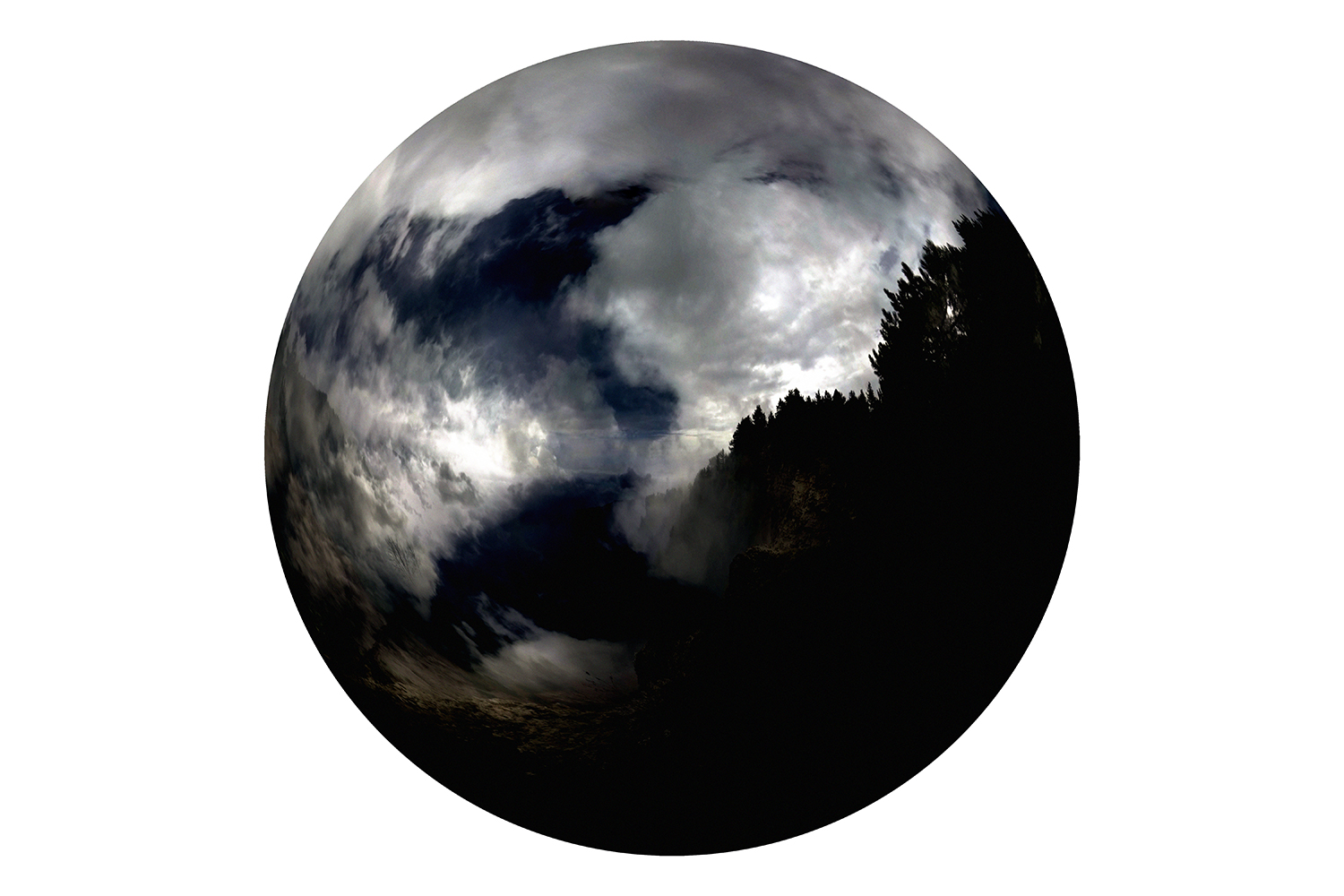

Ruben Spini: In the shows that we have presented together, my visual experimentation provides a kind of scenic backdrop to your presence. I choose natural places, which I transform into a “geography” that is primarily psychic — I want them to resonate with the perceptual states that you explore in your music. According to this extended definition of “space,” I would like to ask you what places you have inhabited the most in the last year, and which you have lost or feel the lack of.

Caterina Barbieri: Framed, forbidden, filtered spaces: windows, gates, walls, and doors. These are the physical spaces that have presided over the last year, which I have spent almost entirely between the walls of my studio in Milan. At first I saw confinement as a radical exercise of absolute, ascetic dedication to music. I did nothing else all day, and after years of centrifugal dispersion, traveling around and doing live performances, it was a marvelous moment of focus for me. In fact, the vocabulary of confinement has a spatial dimension that has always fascinated me and that I feel has been an archetype of the female condition ever since the dawn of time. I think of all the women who were unable to move freely in the outside world and who observed it from a window, concentrating all their energies on the inner world, opening cosmic chasms and building “interior castles” — to use a mystical metaphor coined by Saint Teresa of Avila4, of which I am very fond.

This friction and contrast between negation of the external world and encroachment into the cosmic, visionary domain of the inner world is at the root of the mystical, spiritual vein of many female thinkers, who were able to cultivate a cosmogonic modality of thought that went beyond lives that were often strictly segregated and denied. It is that “undiscovered continent” that Suzanne Juhasz refers to in her wonderful essay “Emily Dickinson and the Space of the Mind,” which you gave me for my birthday, and which goes so far as to consider the transcendentalist American poet as a pioneer of science-fiction literature, due to her extra-corporeal and extra-terrestrial visions.5 All of these images resonate a great deal with my experience of the pandemic. I would tell you that the space I have inhabited most in the last year is in fact that interior castle, where music has always resounded, becoming the compass of my “psychic geography.” In a moment of strong denial and sensory stasis, music “saves” us precisely because of its psychoactive nature, which expands the perceptual horizon toward new worlds. It becomes a sort of cosmogony in the silence of the outside world. What is missing, however, is the sharing of these worlds with others, which we previously took for granted. To answer your question, then, the spaces I lack are those of sharing, of otherness, of intersection and encounter with the lives of others, also accidental and spontaneous, which nourish us and give our existence meaning.

RS: In a letter to Freud, Romain Rolland describes the feeling — typical of the mystical tradition — that one is indissolubly part of the external world as an oceanic sensation, which we perceive as limitless.6 How do you safeguard this experience, which I feel is so effectively channeled into your music?

CB: For me that oceanic feeling is linked to the experience of ecstasy in sound. This is something that I feel particularly strongly with electronic music, due to its extreme physicality, which often manages to strip the sound of its extra-musical cultural references, activating a type of listening that is more anchored to sound as a physical object — with intrinsic properties associated with the sound spectrum — than as a cultural artifact. To preserve this type of experience, I try to avoid the use of immediately recognizable iconic sounds, which risk immediately awakening a specific cultural memory, preferring instead simple waveforms, which minimize extrinsic references and make it harder to identify the source of the original sound (source-bonding).7 I like music that is able to do this and that reduces the listener’s cultural subjectivity and transforms and raises him to the level of an object that is itself fused with the sound. It is a molecular listening: an eternal dance of atoms. It is the deep listening that Pauline Oliveros talks about. Since you mentioned Dirac, also Feynman comes to mind, with his molecular view of sea waves, which closely resembles the idea of getting lost in sound:

Stands at the sea…

wonders at wondering…

I… a universe of atoms…

an atom in the universe.8

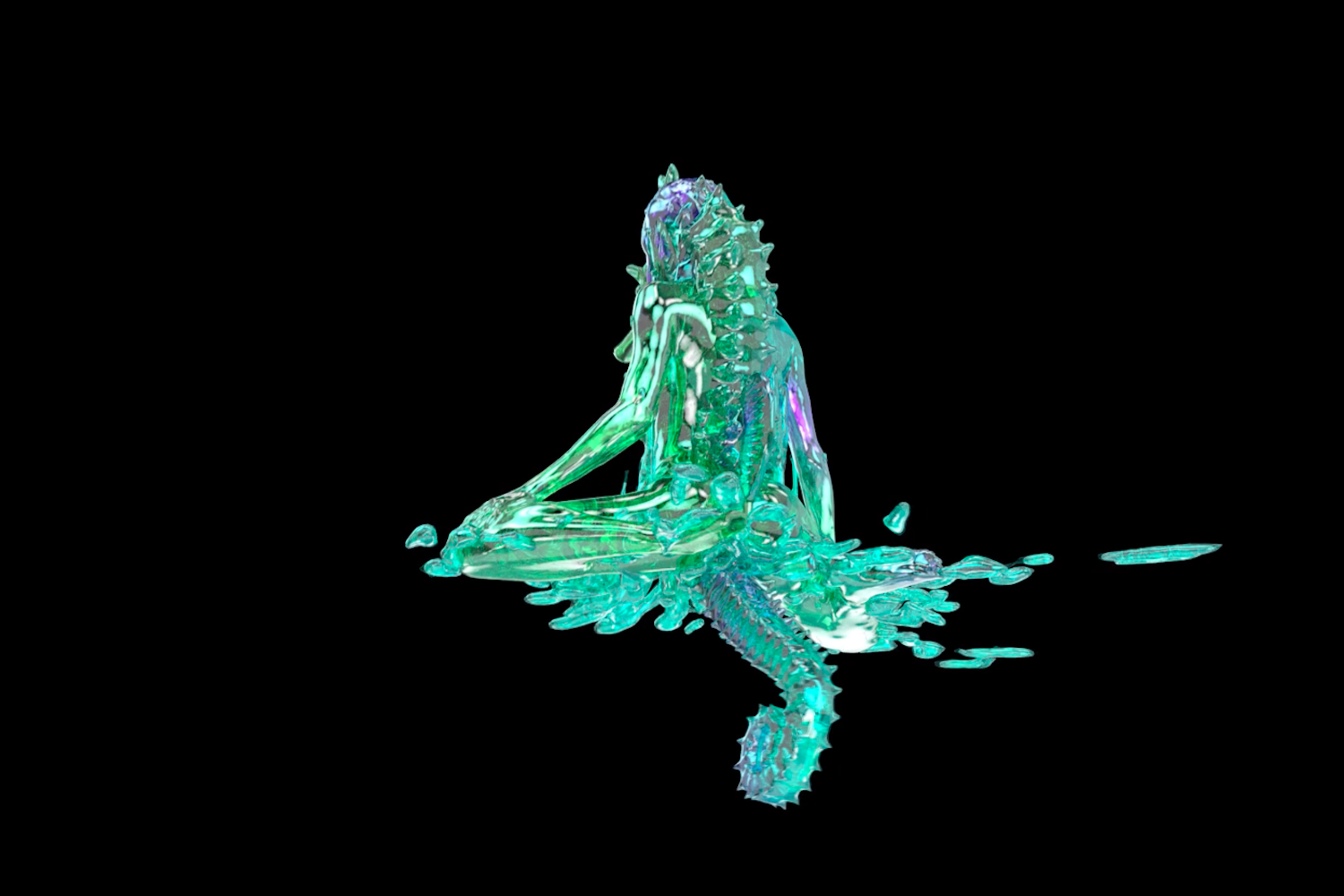

When we listen to a sound we become that sound, because we physically resonate with that vibration of the ether and with that wave. It is a simple physical principle but it is also the key to understanding the ecstatic nature of music: sound transports us outside the limits of our individual physicality and those of our ego, and in this process we embrace a larger and more collective dimension, which transcends the human and the terrestrial, and becomes a cosmic perspective.

Music thus becomes a spiral of connection between the interior and the exterior, the subject and the object: between confinement of the ego and cosmic freedom detached from time and space, beyond the oppositions of duality: it is the continuum of life and of becoming. Like all forms of ecstasy, however, it also corresponds to a kind of double unconscious desire for death — to dissolve oneself in sound, as well as to lose one’s ego and encounter oneself in a more open dimension of continuous transformation. I find it fascinating to see how music represents all of this in a way that is so simple and pure, and at the same time so powerful and so poignant. On the one hand there is this sensual, euphoric dimension of the accumulation of desires, promises, and expectations, which are produced by the continuous tension of music, and on the other there is this desire for abandonment and annihilation, and to be free from one’s body. This intrinsic transcendent quality of music should not just be understood in religious terms. Instead, I feel that music also accustoms you to an exercise in radical immanence: an exercise in being within the here and now. In this sense, sound refines and perfects the art of perception and of listening, and becomes a powerful form of sharing. So for me music is a constant act of telepathy at a distance, which makes it possible to embrace a dimension beyond one’s own ego and to perceive the connections that permeate the universe, even those that are nonhuman.

RS: This also makes me think about your compositional process, thanks to which you bring a precise, unique melody to the surface, chosen from among the many possibilities hidden in the opaque fluid that is musical language… almost as if it were an exercise in resisting entropy. Do you find it difficult to emerge from that vast oceanic feeling?

CB: Yes, I very often find it hard to emerge from that oceanic feeling in music. Nevertheless, the most exhausting, but also gratifying, aspect of my work is that of succeeding in integrating entropy into the creative process; an entropy that, in my case, derives above all from the random aspects of the machines that I use for composing. In fact, much of my compositional practice consists in incorporating the randomness of the modular hardware into my musical writing, in a way that is effective and interesting. To do this I use various generative processes of musical sequencing, also some that are random or semi-random, but all the same it takes me ages to write a sequence that satisfies me [laughs]. After all, a lot of chaotic redundancy emerges from these very technologies: a lot of “anti-content” that needs to be filtered out, manipulated and readjusted so that an intensity of meaning can be produced, which has its own balance and grace. You have to learn how to ask the right questions in order to get good answers, just as you do with oracles, but gradually you learn the strategies for managing entropy and it becomes a “calculated risk.” It has a lot to do with your personal psychology and with your mental pathways, which unfortunately do not give you any respite, and you are forced to travel upon them, even if they are labyrinthine, and even if it takes you centuries. For me this is what it means to work in the studio everyday.

Melodies are an obsession for me; they don’t let go of me for one second. I spend a lot of time unraveling them, as if they were psychic knots or riddles to be solved. So it’s just like you say: they are an exercise in resistance against entropy. They are my anchor and my continuance — to which I always return, in a circular way. But they are also my means of liberation and of therapy. For me a beautiful melody is born from this very delicate tuning between the poles of the unpredictable and the predictable, of departure and return, of the opaque and the clear. It is not always easy to tune these poles, which open up abysses and chasms of meaning into which one all too often falls. But the melody is born from this laceration, which is a wound, but it is also an absurd and impossible kind of magic, which mends the rift in the heavens. It is a kind of motherhood, which multiplies meanings without adding them together. It is the precipice of stars9 — in silence, and in the noise of the unknown.

RS: Also the past year has above all been one of noise, but also of silence. What role do you feel music should have — especially yours, which deals with these extremes? I am thinking about “Aurora Wounds,” the show we presented last September at the Zeiss-Großplanetarium in Berlin, where we narrated the intimate dimension of mourning of a “ghost” that still tries to communicate, but also the environmental dimension of a dying world.

CB: Music has always helped me to elaborate “mourning” and to transform complex and painful negative emotions. But in this year of great psychic desolation, music has been even more for me: it has been the only possibility of traveling at a distance, even if only perceptually or spiritually. For me it has been a form of metempsychosis. In “Aurora Wounds” we thought a lot about music and visuals in these very terms: as a way for a “ghost,” in the broadest sense of something that is immaterial, to inhabit a time and a space, as well as to manifest itself and communicate at a distance. The outside world is forbidden and denied: it becomes this mirage, this ghost to be deciphered. Out there is also planet Earth that is suffering and dying: the ecological collapse that we are witnessing in silence, not knowing how to tackle it. “Aurora Wounds” addresses this wound, this call for help, and this urgent need for telepathy and understanding, also in a cosmic, extra-terrestrial way. I have mentioned the act of telepathy to which music accustoms you, which I feel is particularly precious today, not only so as to address the state of isolation and personal fragility caused by the pandemic, but above all so as to find the strength to “listen” to the ecological collapse, to intimately feel it and to understand what attitude one should take toward it and how to react to it. It is necessary to overturn the anthropocentric position that lies at the basis of this terrible ecological crisis, and to embrace a posthuman perspective within which the harmony of life on this planet can be reestablished.

RS: On April 2 the label Editions Mego released Fantas Variations, a double vinyl LP that contains eight interpretations of your track “Fantas,” performed by eleven different musicians. What do you feel about these reinterpretations and what are the opportunities or limitations of a collaboration compared to the task of composition, which is typically more solitary?

CB: With Fantas Variations I wanted to radically alter the concept of the remix, limiting it to a single track from my album Ecstatic Computation. Thus a single composition, “Fantas,” gives life to eight new compositions by some very different artists, each with their own different approaches and backgrounds that are stylistic, generational, and geographical, as well as expressing their own identity. Evelyn Saylor made a version for voices, in collaboration with Lyra Pramuk, Annie Garlid, and Stine Janvin. Bendik Giske adapted the piece for sax and voice. Kali Malone reinterpreted Fantas for two organs. Walter Zanetti made a version for electric guitar, while Jay Mitta revisited the piece in an electronic singeli style. Baseck made a hard-core electronic version of it, whereas Carlo Maria reinterpreted it for TR-808 and MC-202. Finally Kara-Lis Coverdale adapted “Fantas” for the piano.

I have always perceived my patterns as being cells of a living organism or units of a language that can be infinitely recombined. For me “Fantas” is like a generative entity, which develops its own laws and its own traditions. I wanted to give these traditions a dimension that would be collective and as inclusive as possible. This vision of music as a generative grammar is partly influenced by themes of machine intelligence and technological intimacy, but it also resonates with the Hindustani philosophy of sound, which has had a great influence on my personal way of perceiving the creative process. Within this philosophical and musical tradition, music is experienced as an agent of creation and organic change, which — each time in a unique and unrepeatable way — reflects and manifests nature in the course of becoming, making its cosmic processes perceptible. The raga, for example, is a musical composition but actually it is seen as a living organism in continuous evolution, comparable to a biological species in which every rhythmic and melodic formula is a cell or organ of the creature.10 The composition is the result of this living, breathing, collective oral tradition. I think that Fantas Variations incarnates this vision. It is a celebration of the transmutability of music, and within this transmutability I wanted it to experience a collective, horizontal dimension that is also very intimate and affective. It is a work of support and co-creation, which I find is beneficial in this moment of isolation, and which transcends the usual functional and strategic use of remixes.

RS: What about on an even broader level of “the scene”? In recent months I have detected a new awareness in many artists, in addition to their urgent need to resume their profession. I wonder if the interruption of the entire market could present an opportunity to defend and support the attitudes and ideas they have in common, and what elements might help to establish this kind of sharing.

CB: In the present scenario of breakdown and great contradictions within the creative industry and institutions in general, there is certainly a great desire to reconstruct a more sustainable and independent way of making art together. The pandemic has certainly taken the process of individualistic fragmentation of artistic careers to extremes, a process that is becoming increasingly alienating, arid, and inhuman. Many artists have reacted to this alienation through collective initiatives aiming to reestablish some shared outlooks and unity within the “scene.” One of the initiatives I have had the pleasure of participating in is More Light by Berlin Atonal: a compilation with contributions from nineteen musicians with very different geographical and stylistic characteristics, which have been supported over the years by the festival of Berlin. The internet shortens the enforced distancing of this historical moment and amplifies certain messages on a global scale, which has been positive also for certain debates that for a long time should have been initiated within the music community and that the pandemic has perhaps helped to trigger. Nevertheless, online communities are not always enough to fill the sense of emptiness, and many people feel the need to start again on a “smaller” scale of real physical sharing on a daily basis, in which they can take action in the first person.

In light of all this, in the last year I have made the definitive decision to remain independent as regards my future releases and to found my own label, light-years. I would like this creative platform to be as sustainable and lasting as possible for its creators, celebrating diversity and inclusiveness as the basis of a shared outlook. light-years will become a gravitational field for my own creative orbit, as well as that of other artists and collaborators who inhabit the extensive gamut of electronic music. The project will have a multidisciplinary approach, establishing a dialogue between music, visual art, technology, and design. I would like to experiment with extended audio and video multimedia formats. light-years will put a lot of emphasis on the role of listening and music as agents of change and transformation. Nevertheless, just for now there is no rush. It is a long-term project.

(Translated from Italian by Tristram Bruce)