Terence Koh: It doesn’t seem to fail that every time we do something together it falls apart. Considering this is the second time we are doing this interview… The first time, the tape recorder broke.

Banks Violette: Yeah, I know. This setting is great though. It’s like we’re sitting in a Banks Violette memorial.

TK: It is! Every single surface is glossy black and I put up burnt up crosses everywhere. It’s spooky! It’s black! It’s satanic!

BV: Yeah, your stuff is like all white and mine is all black. The thing that we ended up talking about in the first place was the idea of what would motivate me to actually make something, the criteria surrounding it, and whether or not it’s got the potential for failure, which is the only thing that’s really constant.

TK: There is a built in failure factor in our work. I have always been attracted to the jokers, the morons and the derelicts of the world because they are immune to the idea of failure. I think our work sets up a stage of failure and we both formalize it.

BV: There might seem to be a vaguely formal connection, but when you get down to it, the work is incredibly different. I think the things that we have in common are not the things that are generally discussed. The thing that I’d admired about your work in the first place is that you’re one of those artists that has to do it; that, at the end of the day, if nobody was staring at you, I think you would still be gold-leafing your bathroom, painting your face white and having some kind of fucking cabaret of one with you and your cat.

TK: It’s weird, these days we seem to be at crossroads. I’ve just started doing stuff in bronze, things that are solid, and you’re starting to do things that are falling apart.

BV: Yeah, I think there’s a dialogue. This makes me think of a moronic thing that happened with Steven Parrino, who’s so central to my idea of making work. When his obituary came out, there was written something like, “Here is an artist who influenced a decade of artists from Cady Noland to Banks Violette,” not saying anything but names of people. But art is an interchange. It’s not a competition. Even talking about the way our relationship to one another is structured is something that happens according to a dynamic that is specific to the market, which is utter and total nonsense. It’s all Henry Ford with paint!

TK: I have no problems with all this, Banks. I’m intrigued by auctions and market values.

BV: I don’t think that’s true. I mean the amount of excitement you have about the possibility of working with Yoko Ono is not market-based.

TK: I just want to sing with her. She’s a diva. I’m a diva. I wanted it to be a concert of two Asian divas. My dream is Yoko, Yayoi Kusama and me giving a concert in Tokyo! I love Japan. I think I was born to be a male geisha. I was born in Kyoto but left around 6. So I only have the vaguest memories of it, but I think I inherited the Japanese idea of gestures. I want my work to be a gesture.

BV: That’s another thing I like: you have perfected the public persona. There’s an entire Warholian pedigree of people acting like that. There’s something attractive about the idiot savant kind of thing. Savants are people who can handle one task. They can play chess really well or calculate numbers really well. The amount of information that you synthesize within your practice is a rebuttal to any kind of notion of a savant. What drives me nuts is the tendency toward historical amnesia. I find attractive how specific your historical references are and how you arrange this entire series of people who are marginalized figures in art history: Yoko Ono, George Maciunas, Ray Johnson and a number of people who are weirdos.

TK: Remember the first time I met you? It was in London at Maureen Paley. You were setting up your black drumkit and I was dragging out my black drumkit… I was thinking “Oops! What’s the look on his face going to be as I’m dragging out my black drumkit versus his black drumkit!”

BV: I had a black metal band from Norway there. So it was sort of like, “okay, well, I’ve got the validation of the scary people who kill people.”

TK: Right. And I had no validation.

BV: You didn’t have any freaky long-haired murderers.

TK: Game match. No, let’s just admit that we’re hopeless romantics. The first time you struck a cord in me was in Basel when we were walking past that bridge by the river, looking at the moon and at the moonlight in the river. I said something about how it was romantic and you said, “That’s exactly what the idea of romance is.” I answered that you meant it was the idea of us wanting to jump off the bridge: that’s romanticism, because it would be beautiful.

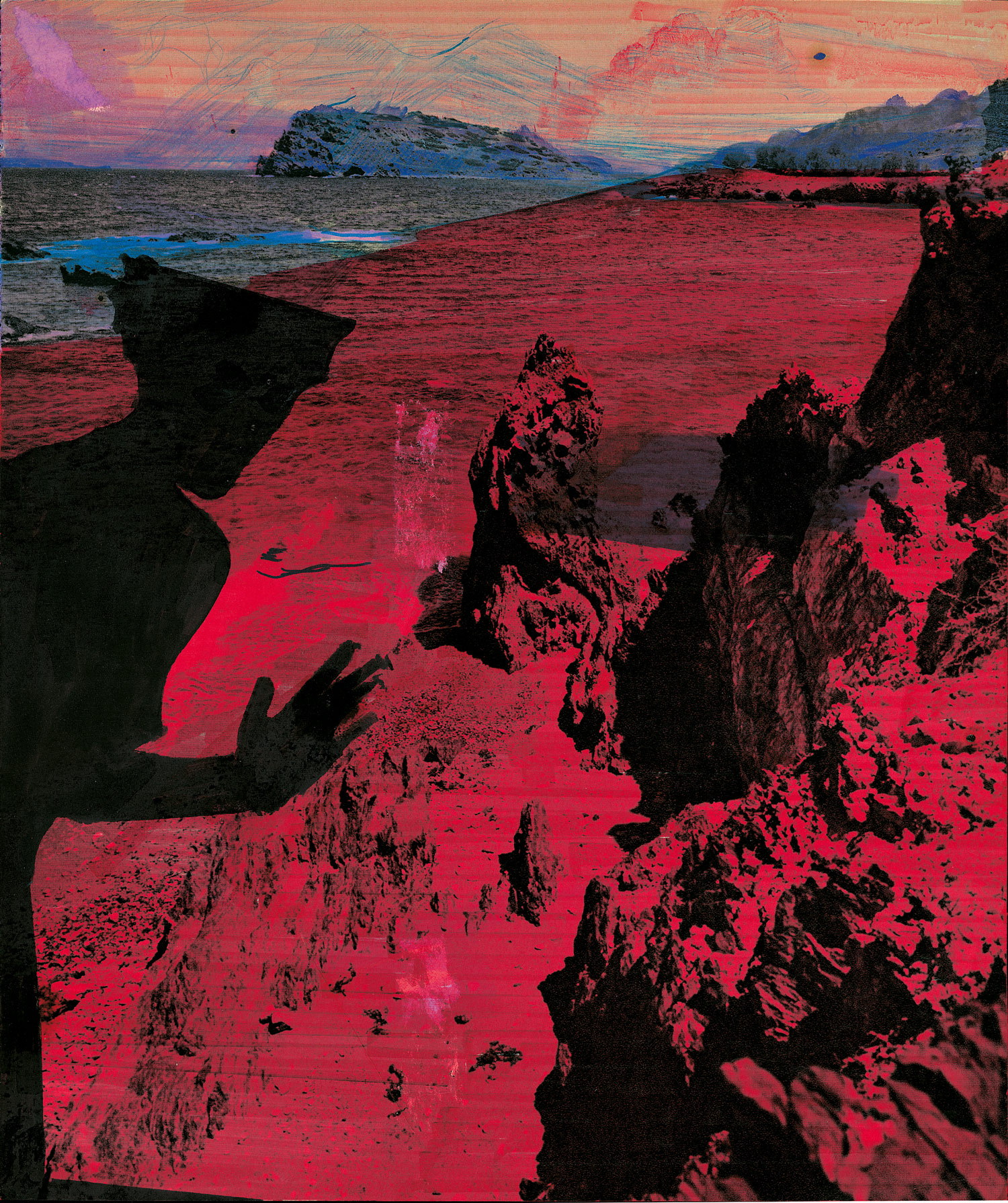

BV: Romanticism is predicated on failure. You know what are the leitmotifs in the Romantic canon in its strict classical sense? Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther is about suicide… and Caspar David Friedrich — Oh! It’s a ruined church. It’s a shipwreck.

TK: Wanting to destroy yourself ’cause you put yourself in that ship.

BV: It’s not even that. You love something so much to the point that you will allow for it to scare you and become more total.

TK: You want something so much that you actually see it.

BV: All the narratives that I use aren’t about violence. That’s not the subject. The violence is proof of belief. For instance, during my show at the Whitney in 2005, Snorre Ruch [black metal musician], who was involved in murders and church burnings, elaborated a fantasy that created a system of belief that people couldn’t disengage from. He was the better artist in that show.

TK: Everybody are better artists than us.

BV: No. That’s not true.

TK: Most are. But I no longer care. I want it all to be inside these days. I want to have no feeling anymore. It’s like in my favorite photograph, a Bruce Conner photograph of a man in a punk band playing alone on a stage and this woman dancing alone. He’s giving it all and she’s giving it all. It’s awesome. No one else might be at the show but we don’t give a flying fuck. It’s like the antithesis to an episode of Jerry Springer. Who do you care about more: Jerry Springer or the rich people?

BV: Jerry Springer.

TK: I prefer rich people.

BV: That’s funny because the idea that capital is the enemy is fucked. But capitalism has done more for gay rights than any kind of notion of grassroots politics. Will and Grace and Disney have done way more. That’s capitalism. That’s not General Idea. In the activists’ history — take Stonewall for example — more came out of capitalism being a motivating force for progressive change. I’ve worked in enough warehouses where I’ve almost been killed by the dematerialized art object. Anyone who’s got a hard-on for that line of philosophy is a Civil War re-enactor with a trust fund.

TK: I have a hard-on just watching you talking about that.

BV: You enact a polarity of poor versus rich. Whereas I have this articulated identity within a particular subculture which is equivalent to my identity in the art world. I am just as involved with that subculture as I am in the art world.

TK: How did you get up to the same level as me in this art world when I know how to suck cock! And I’m gay. And pretty! I have everything going for me.

BV: I got involved in art because I thought that that was the place where there were a lot of cultures, a lot of differences, weirdos. And there aren’t. But you’re good, strange, fine, yourself.

TK: Once we were drunk and we were walking on Canal Street and I said, “You’re like a Jasper Johns for how you are in your studio, and I’m the Andy Warhol partying every night.” But we both are total nerds. We both watch Star Trek and masturbate to Caspar David Friedrich paintings.

BV: Yeah. In opposition to what has been canonized as pop art, I’d rather create a reciprocal relationship that is more like, “You’ve got to catch up with me. I’m not going to make this easy for you.”

TK: You’re very difficult, Banks. And I’m very easy.

BV: I don’t think you’re easy. You’re easy socially. That’s a different thing.

TK: You’re easy socially too. But at our core we are both pretty sad people.

BV: That hostility that I get lumped with much more than you, it’s not really hostility. I just think that things could be better.

TK: To love, you have to hurt. To me your work is intrinsically sexual. Black. Slick. Stuck in my ass.

BV: That’s so funny because I have such a kind of non-sexual relationship to it.

TK: We both masturbate to our work. Maybe you do it psychologically. You’re the intellectual.

BV: Your just sexual.

TK: You keep it inside you. Almost like mojo. We’re introverts. We both trap so much inside.

BV: It is more majestic. It’s about your investment in it. Active versus passive. Your fantasy is always going to be better.

TK: It’s the fantasy of failing, again. We both set a stage for failure. In the end it’s about staging something so we can fall.

BV: It’s the site where you can project belief.

TK: Exactly. Back to Caspar David Friedrich. What’s your favorite painting by him?

BV: Oh. The Wreck of the Hope, which is the iceberg painting that has the fishing vessel but it also looks like the Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis) by Robert Smithson.

TK: I have a few favorite paintings. The one with the sea, the church and the snowscape — I dedicated a whole installation to it at the Zurich Kunsthalle: a room covered in white powder, Untitled (After Caspar David Friedrich After Banks Violette), 2006. And again, here you are positioned as the opposite: solid, black, slick. But both are ultimately about destruction.

BV: My destruction is always mediated. For instance, I know this guy who is charged by the Smithson Estate to recreate certain pieces. He remakes the Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis) piece, which is one of my favorite pieces —

TK: That’s where it connects us, I think. It’s like stained glass, broken glass. You’re an idea of perfection, light filtering through the stained glass window in a sense. And I’m like the crack in the stained glass window. The little crack.

BV: In Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis) — a purely processed artwork — there’s a dumptruck, a flatbed truck that has 100 plates of tempered glass; it pulls up, the bed rises up, the glass slides out and it smashes. That’s it. Except, what actually takes place is that there’s this guy who wades into the middle of it and pushes it into a formal composition. There is actually a composed dimension. So I’ll smash things, but always in a frozen and aestheticized form.

TK: Freezing what’s broken so we can remember it: it’s like your smashed bottles on a stage and my funeral with smashed beer bottles — there are so many things that appear in both our works: beer bottles, drumkits, my white powder, your white salt and secret performances.

BV: In your work, if it were purely a process or purely a gesture, there would be the idea of the transcendence of a moment. But instead what you do — where it’s a carefully controlled performance — or what I do — which is a mediated composition — is actually ruled and directed and doesn’t have this kind of transcendence.

TK: We’re trying to make things disappear. We’re trying to be magicians in a way. Or sorcerers. I’m the witch and you’re the wizard.

BV: Well, I have such a polemic involved with the performative aspect of what I do, which is trying to force this situation between two contexts that are constructed as utterly alien from one another. That’s why when I had Sunn O))) play in London I didn’t let anybody see them, because what they do is incredibly important and sophisticated but if it was shown to an audience that had no understanding of that, it could easily become a punch-line.

TK: Like a complete fetishization.

BV: Exactly. By obscuring the whole thing — there was a guy in a black robe in a coffin screaming, smoke machines, and you couldn’t see that far in front of you — nobody got to see that. Instead, people just had this experience of something divorced from the identifier.

TK: I do smoke machines and I’m the white centrality of the performance itself, the cloud that will disappear. I love nature. I remember living in Iceland for a few years and swimming in the lakes. I loved the calmness, the quiet, looking at the clouds, but at the same time there is this absolutely terrifying aspect of swimming in a lake that could be bottomless. This vision of getting trapped in absolute blackness shakes me down to the core. Perhaps this is where my fascination with myths come from. The spirit of demons and the unknown. It’s almost a primal fear. I think I create objects as sacraments of fear. Talismans to ward off evil spirits.

BV: But that’s the thing — your identity is constructed as something that you have to make a case for. So you put yourself there. Whereas for me to put myself in the performance… I’m a straight fuckin’ white guy! Nobody would have any problem with that… I had this funny experience. When I did the Whitney Biennial [2004] I was still working for Robert Gober. He went to see the Biennial, he came back and said, “Well, I guess I’m the last of this political generation.” He was talking about the Biennial as an apolitical situation. I thought, “Wow. We, at this current moment, are at a different place.” By virtue of just simply presenting difference as something that you don’t have to foreground, the articulation of a sovereign individual is inherently political. So I thought of you, and how just being what you are is incredibly political.

TK: Those two gigantic white chocolate mountains at my Zurich Kunsthalle show were based on the idea of the Twin Towers. I did a secret ritual for all the people that died. I don’t think it’s about being actively political but rather letting these reactions manifest themselves in the artwork.

BV: I think of the micro-communities, because that’s where I came from: subcultures. If you’re working from an antagonistic position, which I think you are, aside from your bullshit “I like rich people”…

TK: That’s not bullshit, Banks.

BV: I think you’ve managed to figure out a way to manipulate it to your advantage, which is still hostile.

TK: Thanks for understanding me.

BV: It comes back to mediation again. I am interested in what takes place in true crime novels. Like, a crumpled pack of cigarettes is a crumpled pack of cigarettes unless it’s a piece of evidence. So, what I mean is that you activate things by you performing them. I activate things by associating them with a narrative performance, an act of violence, something out there, or my involvement with musicians.

TK: We’re like criminals dropping clues.

BV: It’s forensics.

TK: Like The Da Vinci Code movie. You realize how violent religion is. I’m working on a piece which is a recreation of The Last Supper. So the disciples and Jesus are cast depicted as skeletons. It’s a cast of my body on the table, and Jesus and the disciples are devouring me. There are ants and bees crawling around everywhere eating me too. And it’s all cast in gold. I’m moving away from shiny bright lights.

BV: I think that this is what you have in common sculpturally with post-minimalism. This is where that’s always held up as a politically neutral, abstract kind of moment. You have somebody shattering glass or throwing a meat cleaver into the side of a museum…

TK: I think we’re both interested in the cutting. I think you’re fascinated with the grotesqueness of actually cutting skin and flesh, and I’m repulsed by it completely.

BV: I’m interested in it being a beautiful thing.

TK: I’m interested in it being a horrific thing. Although, I think we both want to do beautiful things.

BV: But our standards for beauty are a little bit weirder. Beauty is supposed to be trans-historical, trans-cultural and totally neutral. Tell that to the fat girl vomiting!