In July, Camden Art Centre opened “Soft Acid,” the first institutional exhibition of Tenant of Culture (the anonym for the artistic practice of the Dutch practitioner Hendrickje Schimmel) in the United Kingdom. The research behind this ambitious, site-specific presentation was informed by the historic and contemporary processes used in textile production, and their wider relationship to consumer waste, mass labor, and environmental pollution. As Tenant of Culture, Schimmel has become known for her sustained exploration of the fashion industry, overproduction, and the intense cyclical nature of trends, with her skilled and materials-driven practice transforming used and discarded garments and accessories into complex, amalgamated sculptures and textiles. Philomena Epps met with the artist, mid-installation, on a humid summer afternoon a few days before the exhibition was due to open.

Philomena Epps: I wanted to initiate our conversation by inviting you to talk about the research you undertook in the archives at Camden Art Centre while preparing for the exhibition, and how that process then led you to the British laundry industry.

Tenant of Culture: Camden Art Centre started as an artist-run space in the 1960s called Hampstead Arts Centre. Martin Clark [Camden Art Centre’s director] told me that there had been lots of workshops here in those days. Workshops are such an intrinsic part of my practice, so I wanted to find documentation of these events. In my 2021 exhibition “et al.” at Kunstverein Dresden, I ran workshops for two weeks and then exhibited the results for the remaining run. In the archive, I found a flyer for an exhibition that took place in 1967 called “The Londoners.” It was about industries that employed large percentages of the population, and it was there that I read about the laundry industry. I’d never heard the phrase before, and it initially intrigued me because it sounded so domestic. I started doing some research. Although it was hard to find anything at first, I managed to find two books on the subject: English Laundresses: A Social History, 1850–1930 (1986) and Steam Laundries: Gender, Technology and Work in the United States and Great Britain, 1880–1940 (2003). Especially the last one elaborated on how this industry was forgotten within the history of the industrial revolution because of its associations with domesticity and femininity. I also read about the rising standards of cleanliness, and the upwards mobility that came from looking clean and wearing bleached and startched whites. The middle classes used their clothes to distinguish themselves from the working classes, who couldn’t avoid dirty clothes because they worked in the coal industry, for example. In these rapidly urbanized environments, there was also an increasing anonymity, so it was even more important to present a certain way for a good first impression. I find all these things very engaging, particularly how something might become a trend because of wider material circumstances.

PE: I’m assuming the majority of the workers in the laundry industry were women?

ToC: Exactly. When you think of the era of industrialization, you might associate it with men working in steel mills, but the laundries almost entirely employed women, although they were still run and managed by men. It was married women, too, which was unusual. The work was so powerfully gendered and associated with domesticity that it didn’t unsettle the gender standards.

PE: I was reading an article [on striking-women.org] that explained how despite many women being employed during that period, their income was not accurately recorded within the sources that historians have relied on. If their wages were seen as “secondary earnings” to men’s wages, they wouldn’t have included it on the census, and it therefore didn’t appear in statistics.

ToC: That’s really interesting. I also couldn’t find any personal accounts from laundresses. There has been a similar lack of information regarding the industrial history of fashion. Fashion has been more commonly associated with the beauty industry, rather than heavy industrial activity. It was important for me to make links with contemporary industry. The processes used in the laundries informed modern-day mass production. The same machines are used in factories today. This contradiction interested me, particularly how the machines that cleaned items are now used to make them look artificially dirty or faded, something like acid-wash denim. I also looked at the treatments and finishing processes used on sportswear and activewear, such as waterproofing or sweat-proofing. Before these items even hit the shops, their materiality has been deconstructed and broken down. The title of the exhibition, “Soft Acid,” references the chemical agents used to soften garments and to make them comfortable to wear. I liked the name, as you don’t commonly think about bleach or acid in this way. I also wanted to consider the dyeing practices that are used before something even becomes a garment. These finishes and materials require significant amounts of water to make. I’ve previously looked at post-consumer waste, but I became engaged with water wastage and pre-consumer waste. A garment is only 5% of the raw materials used to make it. 95% is invisible waste, largely consisting of water. That water, which is being used to feed crops, will then be contaminated and lined with chemicals and microfibers.

PE: In addition to vast levels of waste, fast fashion has been directly contributing to water pollution and carbon emissions.

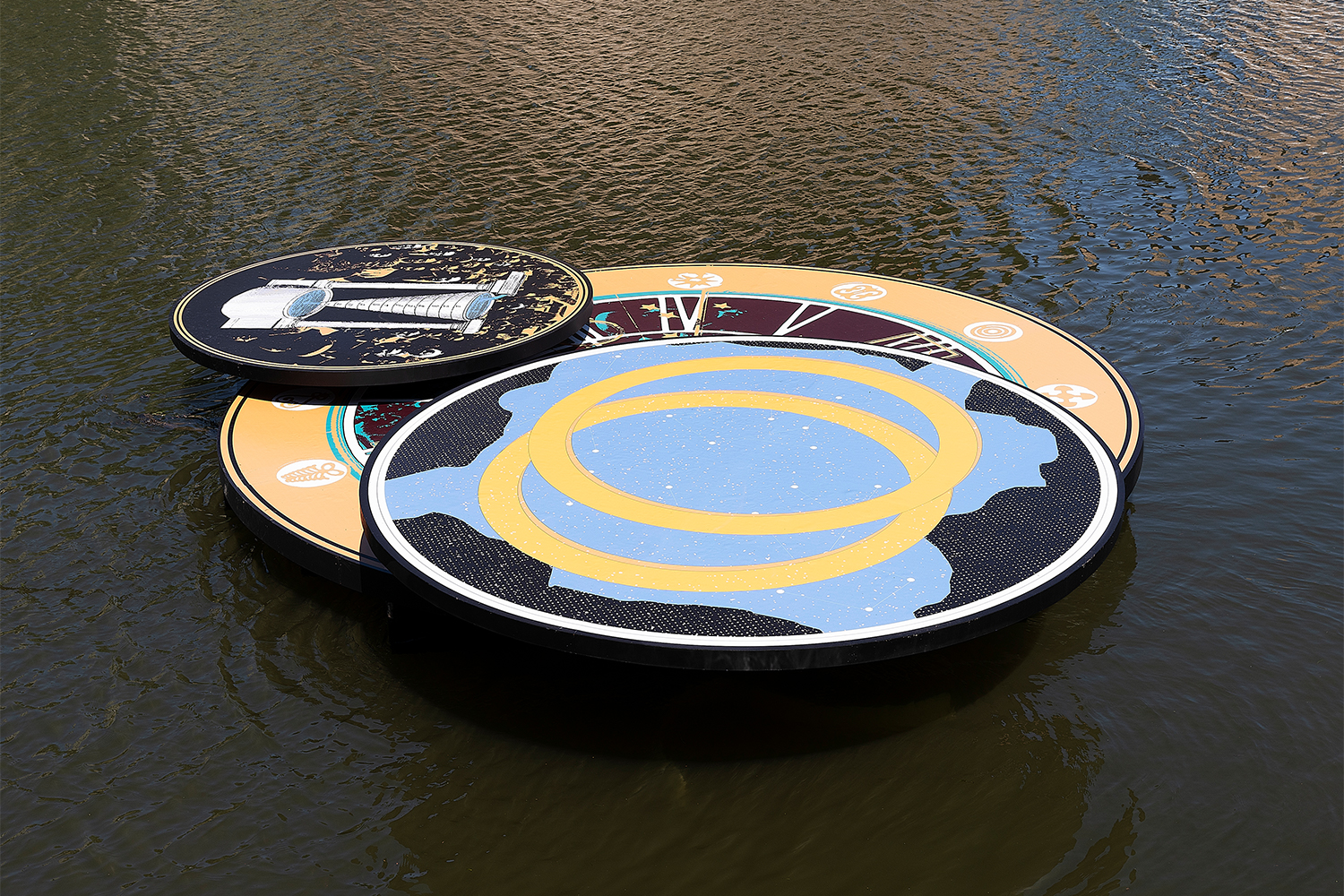

ToC: These effects are also invisible. I wasn’t aware of how much water it actually takes to make these garments. The UK and Europe have very neatly tightened their water laws rearding water pollution and rely almost entirely on production elsewhere, but water doesn’t care about boundaries; it flows all over the world. When I went to a garment factory to have the large-scale denim pieces Soft Acid (Series) (2022) dyed, I discovered that they were one of the last remaining factories in London that does it. The legislation is so strict that these factories can’t afford to do it anymore. They’re being forced to off-shore it, which happens continuously in the fashion industry. The Residual Hue (2022) shoe sculptures were dyed with waste ink collected from fabric printers by Aliki van der Kruijs for her project Afterseason, but for these denim pieces, I wanted to choose colors that were not associated with the natural world or anything organic. The yellow dye is my favorite, it looks so toxic.

PE: It looks hazardous, almost dangerous.

ToC: As it should be! It is dangerous! I wanted to walk the line between looking abject, grotesque, and unfriendly, but still somehow sexy.

PE: It’s seductive. How did you construct these textile works?

ToC: I bought all this acid-wash denim off eBay and from charity shops, and sourced all these pre-bleached and pre-washed items, and started deconstructing them. I always like to let the garment itself guide me. As soon as I started sewing them together, you get a map of the stains and washes that have been used. Some are lasered on. You can have an abstract idea of how something is constructed, but once you start handling the material, it always changes. You start to understand more about the supply chain and the intention behind its design. This material knowledge is really important to me — that’s when it really starts to live. These items become an archive of their own processes. The seams reveal whether it was stitched together before or after being dyed. Items which were fabricated more cheaply can be easily dismantled.

PE: In addition to being stitched to one another, the different sportswear materials in the Dry Fit (Series) (2022) also appear tied and bundled together?

ToC: My own selection process has the potential to create waste, so I make sure to use the whole piece where I can and not cut it into fragments. It is an intimate and multi-sensory process. I use bungees and elastics, and sew toggles on the back so they can be tightened and tied up. It would be over ten meters long otherwise, like a sort of sea monster. The bunching also refers back to laundry practices, like the action of wringing out or hanging a garment.

PE: The adjustable aesthetic feels more practical, somehow multipurpose. It also means the patchworked sculpture is three-dimensional and not flat. The work commands a strong sense of corporeality, which triggers associations with its original purpose as a garment.

ToC: It is really important to me that you can still somehow see how you might style it. Dry Fit (Series) Green has a hole in the middle, so it becomes almost wearable. Another segment has a sleeve hanging out. I want you to encounter the textiles in the exhibition space and perhaps think, “I have some jeans that might match that quite nicely.” I don’t want to completely leave the realm of fashion. My methods are rooted in artistic practice, but I see myself as a fashion practitioner rather than an artist. I always mimic and stay close to the assembly methods that the garment initially had, despite sometimes exaggerating them. Here, I used sportswear techniques, and on the other pieces, I used denim stitches. It keeps you in the same atmosphere.

PE: I’m intrigued by your relationship towards the gallery space as a quasi-boutique. You often riff on fashion merchandising, such as using glass-and-steel display pedestals that evoke high-fashion shop design, and have previously made mannequin busts out of plaster. What is your relationship to these specific environments?

ToC: I like to sometimes appropriate the luxury feel of a shop, particularly the persuasiveness of those which use stainless steel and transparent materials. The installation at Camden Art Centre is comprised of a bespoke hanging system based on the system of pipes used in dye factories. I was interested in how the aesthetic of that industry is being emulated by high-end fashion display mechanisms, such as the Balenciaga flagship store. It is strange that this aesthetic is being used in shops without actually addressing the means of production. I don’t usually use a living body or a full-body mannequin. I don’t want to render features or take it too close to the human body. The continued absence of the body is crucial, otherwise it relates too closely to identity or styling.

PE: I read an interview you gave in which you mentioned that you aren’t interested in blaming these issues regarding consumption solely on the individual, and prefer to comment on wider systemic issues regarding globalized supply chains, capitalism, and overproduction. Perhaps that is also related to the lack of bodies in your practice?

ToC: That’s really true, I want to stay away from blaming individual consumers. Consumerism should be referred to as “producer-ism.” It is not the fault of the consumer; it is the fault of the producing entities. They produce so much surplus, and they create elaborate strategies so that you consume that surplus. It is a personal enquiry for me. It all comes from a love of clothes, not a hatred of fashion. When I was in fashion school, I found it so hard to get a conversation going that wasn’t just about fashion as image. I wanted to talk about how something was produced, start to finish, but found that information was totally inaccessible. Fashion was always discussed as something ephemeral, fleeting. It was never talked about in a concrete and material sense.

PE: Through this enquiry, you’re stating that you’re also part of this system and part of this culture, which brings me to your chosen moniker: Tenant of Culture.

ToC: I liked the associations between being a tenant and being a consumer, being a participant who is subjected to these more powerful structures. The phrase Tenant of Culture is also based on an allegory that the French historian and theorist Michel de Certeau used to talk about the hierarchies that exist between producers and consumers. He specifically used the term to address the kind of tactics that consumers use to defy the strategies of producers, such as misusing, personalizing, and reinterpreting mass-produced goods.

By altering and recycling garments in my work, I want to unsettle the notion that consumerism is a passive practice. In the workshops that I have run, the energy of remaking is so much fun. I don’t give instructions aside from showing some techniques. People have a natural intimacy with clothes because it’s a daily practice, and there is pleasure in assembling an outfit. Although, I have sometimes noticed that people find it really hard to cut up an item that has a label on it.

PE: Because they attribute value to that label?

ToC: And a sense of loyalty.

PE: Brand loyalty!

ToC: It’s cleverly created. It’s important to realize how we are being manipulated as consumers, such as through the acceleration of planned obsolescence.

PE: Can you expand on these strategies of planned obsolescence?

ToC: In technology, it is more evidently seen through battery life. But with garments, you have both material and psychological obsolescence. If you stitch something with rubbish thread, it will fall apart more quickly, even if it is a great quality fabric. Then, it will be cheaper to replace it rather than restore

it. When the garments are cheap to buy, you also might not think it is worth restoring. In addition, if you make something look very current, then it will become obsolete quicker, thereby shortening that replacement cycle. There is so much money invested to manipulate people into making these purchases, but it isn’t real demand: it is artificially created demand.

PE: What do you think will halt this frenzy?

ToC: Legislation. We need laws. This is down to legislation anyway: the shifts in trade policies, strategically planned economic globalization, and the dismantling of unions, to name a few. We can’t find the answer by looking deeply within ourselves and buying organic baskets! Production wise, anything goes now. If you can’t do it here, you can do it somewhere else. It’s just a race to the bottom. Food legislation is very strict, you have to declare on the label where it was packed, where it was grown, but this is not mandatory in the fashion industry. Governments are acting like entrepreneurs, rather than protecting people from production practices that are causing harm.

PE: Constant trend cycles are a key part of this surplus of created demand. Earlier, you mentioned how trends also relate to wider circumstances in society. In your “Eclogues ” works from 2019, you considered the prevalent rustic aesthetic and the romanticized nostalgia for the pastoral idyll in contemporary fashion, such as the proliferation of peasant blouses and milkmaid-style dresses, in addition to the wider “cottagecore” agricultural trend. Then, in your 2020 exhibition “Georgics (how to style a chore coat)” at Galerie Fons Welters, you looked at the rise of workwear, such as the rural “chore” jacket, which had ironically been very popular with urban, desk-based workers.

ToC: It was in response to a politically fraught time. This pastoral tendency, to refer back to a simpler, apolitical time, is as old as the Greeks. With that rustic milkmaid trend, I saw it everywhere, from all aspects of the market, low to high end. I was also seduced by it; I was wearing it, which made me more interested. I want to look into something once I’ve fallen for it. I don’t want to critique from the outside. I am the most switched on when I am intrigued by something’s ambiguity or contradictions. These trends remind you that you are part of a much larger subconscious. Every garment has a history that is very elaborate. There is not that much innovation in clothing styles; we wear largely the same idea of garments that we have since the industrial revolution.

PE: It’s more psychoanalytic, that approach. You’re reflecting on and questioning your own consumer behavior. What do you think the current, or even future, trends are?

ToC: I’m always behind the trends. I’m not in the business of trendspotting or forecasting, despite finding it fascinating. Sourcing materials is 70% of my practice. It can be quite unpredictable. I source my materials from the secondary market, so I’m looking backwards. People have already moved on from these items but they are still in circulation. I see them as not yet decomposed images from the past that still need processing.

PE: I like your subversive use of the phrase “secondary market,” which is at odds with the way that term is conventionally understood in the art world. You’re talking about discarded and rejected scraps, whereas in the art market, secondary sales often assert and reinforce an artwork’s value and reputation.

ToC: I know that I’m misusing the term. It also means something different in economic theory. I couldn’t find a better word for it. Vintage means something else, as it similarly signifies a sense of value. These clothes are very recently made — some are less than six months old. There are stacks of items in charity shops that still have the original tags on them. How are consumers being persuaded by producers to buy something and get rid of it again so quickly?

PE: In his essay “Tenant of Culture, Ragpicker of Fashion History,” Jeppe Ugelvig draws a comparison between your practice and the historical figure of the ragpicker, who salvaged refuse and other discarded objects for the purpose of recycling and reusing them.

ToC: The ragpickers collected glass that could be melted down and reused as raw material, or would skin dead cats and dogs and make them into furs. Similarly, in the workshops I run, you are constantly evaluating materiality, seeing what a certain fiber or textile piece can do, and then turning it into something else. It is all about seeing how something can be transformed and not just seeing it as a solid entity. We should feel agency within the material world, rather than being passive bystanders. We have lost touch with the making of things. We have been alienated from it, always encouraged to buy something new.

PE: In your previous works, through the use of cement, epoxy clay, and wire armatures, the garments and shoes in your sculptures have looked like they are decomposing, or are even fossilized. In the Extensive Range of Carrying Options (Series) (2022), where you’ve made a parka, a trench coat, and a blazer from recycled plastic accessories, the associations now read differently and could even seem futuristic.

ToC: It’s true, that idea of plastic as progress. The materiality always relates to the subject matter I’m working on. When I was working with rustic materials, the aesthetic related to that trend. I’m now working with no organic materials and using this synthetic and noxious color palette. Those sculptures are made from those transparent handbags you see everywhere now and plastic mannequins. I bought used ones which were yellowing and murky. I was also thinking about Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1986 essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” and the container or receptacle as the first technology rather than the tool. This relates back to the women’s laundry industry being largely forgotten because it was so heavily associated with domesticity and femininity, and questioning who writes the history of an industry.

PE: Your exhibitions could be read as “research-in-progress,” with the material improvisation reflecting your current research during that period of time.

ToC: That’s exactly it. I’m also not offering solutions or a proposal for a better world. My practice is a constant material enquiry.