Who has the right to claim a place as home? How familiar is the foreigner, and where can he or she be found? What does it mean that “I” is another? These are some of the questions Susan Hefuna addresses in her art. Since November 2009 the German-Egyptian artist has been involved in Mapping Vienna, a still-in-progress, year-long, site-specific project in Austria’s capital, developed and undertaken in cooperation with gallerist Grita Insam. Mapping Vienna consists of 15 interventions in select public spaces, each one accompanied by a unique signature yellow postcard that uses typography to draw attention to the fact that xenophobia and orientalism, the perception of the East as a mostly negative inversion of the West, is a matter of form, a cultural code that determines how and what we see in the foreigner.

Recently, visitors to and natives of Vienna may have come across a black ‘Arab’ or ‘Turkish’ tent pitched at the MuseumsQuartier Wien (center for arts and culture), a busy complex of courtyards of mostly baroque architecture, which during the Habsburg Empire housed the Imperial Stables. Closed on all sides, the tent creates a private, segregated space in one of Vienna’s most public places. Segregation indeed, not lack of communication. There’s a message written on the tent’s outer skin: “Knowledge is sweeter than honey.” In another intervention Hefuna designed black, body-length cloaks — wearable tents if you will — to be worn at Vienna’s annual Opernball (Vienna Opera Ball), an occasion where the city’s white upper class traditionally celebrates its cultural hegemony. Open only to the wealthy and the ‘very important,’ the Opernball appropriates a public place (the Vienna State Opera) for a private event, shutting out most of the city’s population. When Hefuna, her gallerist Grita Insam, and a Viennese art collector donned their cloaks and joined the ball, they did more than violate the dress code. Reminiscent of both the Muslim hijab1 and the cowl worn by Christian monks with the words “patience” and “beautiful” or “Vienna” stitched onto them in large colorful letters, the costumes insist on the presence of the excluded “other,” not as mirror, stereotype or symptom, but as reminder of that strangeness within ourselves.

Like most European nations, Austria looks at the East from an orientalizing point of view. Muslims (roughly eight percent of Vienna’s population) are perceived as suspicious ‘others.’ A woman’s headscarf or a ‘Turkish’ tent evoke a deep-seated, irrational Islamophobia that has its roots in the 16th and 17th centuries when the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire competed for control over Southeast Europe. Many Austrians remember the sieges of Vienna in 1529 and 1683 as if they happened yesterday; they serve to justify the racist urge to patronize Muslims and vilify Islam. In this context Hefuna’s interventions insist that the foreigner is always already part of the family. The tent is a particularly powerful intervention as it forces us — it forces me — to ponder the question: What kind of knowledge is sweeter than honey? The ‘naked truth’ of the orientalist-scientist who cannot distinguish between knowing and unveiling, who believes he will remain untouched by the objects he dissects, who fantasizes about breaking through the tent’s skin? Or the wisdom of the ‘orient,’ which assumes that knowledge is fluid and provisional, transient and experiential, the result of a relationship between the subject of knowledge and the object of knowledge that affects and changes both of them. A kind of knowledge produced on a carpet rather than on a chair or a desk.

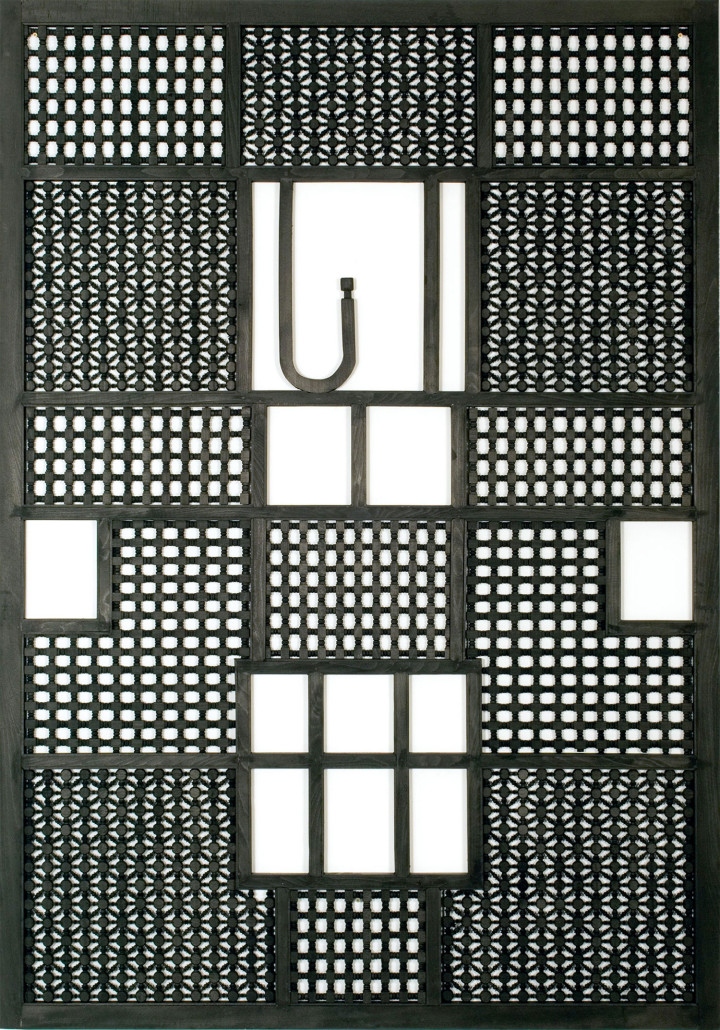

Before the opening at Grita Insam on November 19th there will be one last intervention produced in collaboration with the Freud Museum: a series of wooden masks hung on walls, and a mashrabiya2 with the inscriptions ANA (I in Arabic), ICH, MYSELF. Inspiring the project are those masks worn in traditional Swabian3-German Fasnacht.4 Hefuna kept the types but used her own face to make each mask. I am intrigued by the location! The gallery is located in the Berggasse 19 storefront in which Siegmund Kornmehl operated his kosher butcher shop until 1938. In 2002 the storefront became part of the Freud Museum, which is located in the same building on Berggasse 19 where Freud lived and worked from 1891 until 1938, when on June 4 he was forced by the National Socialists to flee with his family into exile in England. Since the storefront gallery cannot be entered, I must sneak a look through the window, like a voyeur, peeping into an analyst’s office. The masks and the mashrabiya inside mirror my own disguised detachment on the outside. I’m drawn into the analytic relationship: as subject I find myself on the screen of the other; intimate strangers, the face is the mask.

Drawing plays an important part in Susan Hefuna’s body of work. Ink and pencil on multiple layers of tracing paper, the drawings work with abstract patterns and configurations. They evoke molecular structures, maps, cityscapes, but also musical scores, dance notation, a choreography of dots, lines and curves. Though abstract and formal, the drawings suggest the presence of a body, perhaps two bodies: that of the artist and that of the viewer. In their fragile beauty — some of them are literally harmed, pierced, perforated, bleeding, stitched together — the drawings are at once terrifying and hugely attractive. Terrifying in that they don’t conceal the wound that lives within them, a wound every foreigner knows; attractive because they draw strength and orientation from their pain and vulnerability. Although highly seductive, there is nothing voyeuristic about Hefuna’s drawings. The two layers protect one another, inviting me to embark on a journey. In fact it is the viewer who makes sense of the patterns and grids, who decides what to foreground and what to push back. In this the drawings are deeply human. I think of them as a “corporeal map” (a concept hard to grasp within Western notions of rational space), a way of relating to a place, a city, a body that combines the experiential — always corporeal, always sensual — with the abstract without ever subjugating one to the other. In their fleeting presence Hefuna’s drawings remind me of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. It is the imagination that makes us humane. Science alienates.