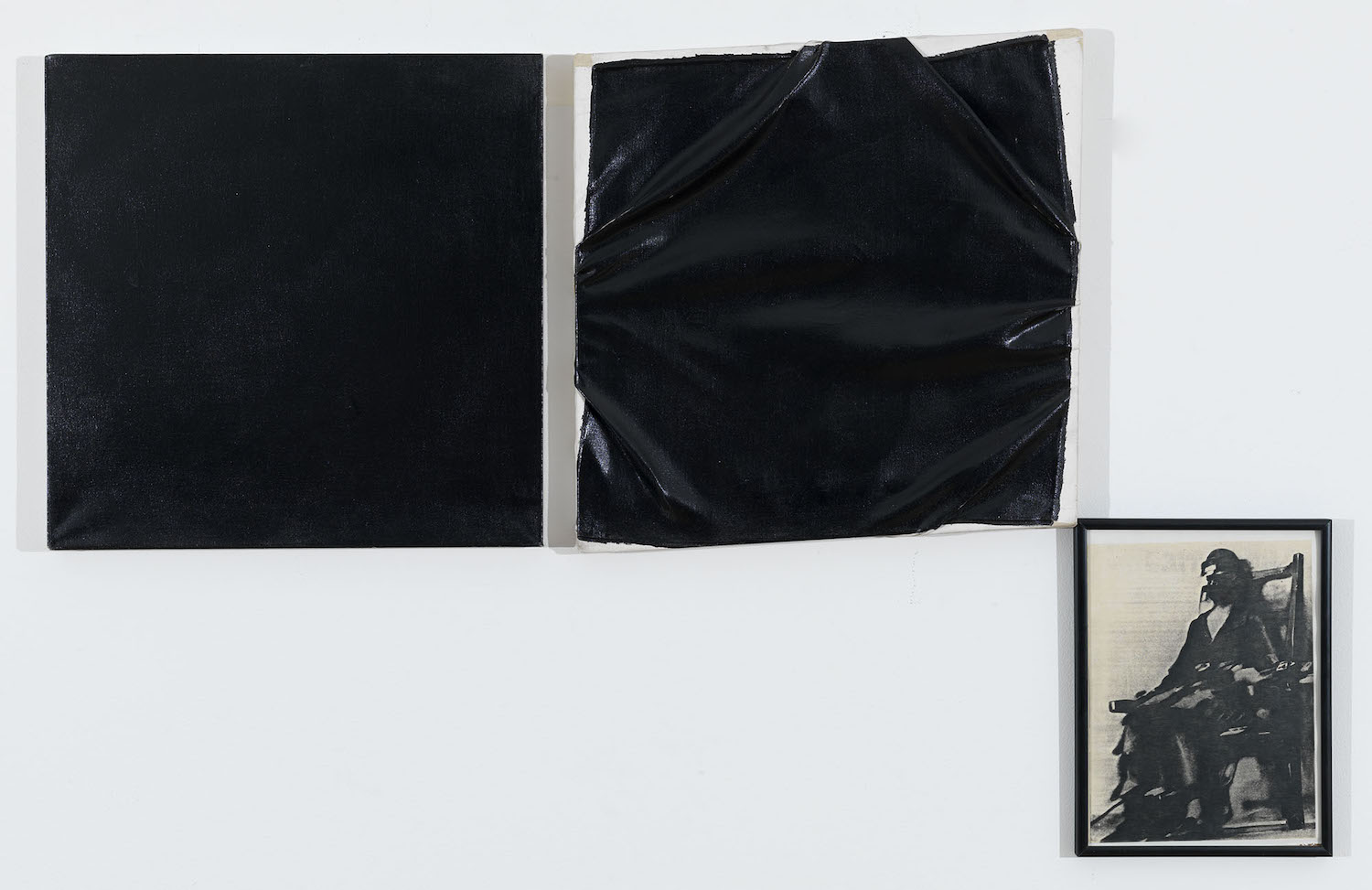

For all the mythology that dogs the legacy of Steven Parrino, two decades after his death at the age of forty-six, his work maintains a cryptic anarchism. This jewel of a show at Gagosian’s intimate Basel location balances the introduction and deep dive, making it enjoyable for those only passingly familiar and fanboys alike. It’s an achievement of tight curation and Parrino’s singular ability to connect and alter the threads and legacies of concrete art through Pop art. The entry of the gallery is dominated by Untitled (2004), a gigantic pyramid of four triangular canvases hinged together and inverted so that it balances on its tip within a corner. Like his most iconic works, its slick black monochromes have been unstretched and reattached to their stretchers so that folds, raw canvas, and plays of highlight and shadow create new compositions of suggested randomness. Equally phallic and central, the work is a seminal display of sex appeal, freshness, and the nonbinary medium. It’s undeniable that it belongs at Dia alongside Richard Serra and Michael Heizer, yet the lack of passion for Parrino, especially while he was alive, sits squarely in the crown of embarrassments for the New York and American art world. Three decades on, Switzerland remains the major locale of display and understanding. An outsider’s work, so openly questioning of rules, treated as kindred in this exclusionary and inflexible country acknowledges the multiplicitous and paradoxical nature of Parrino.

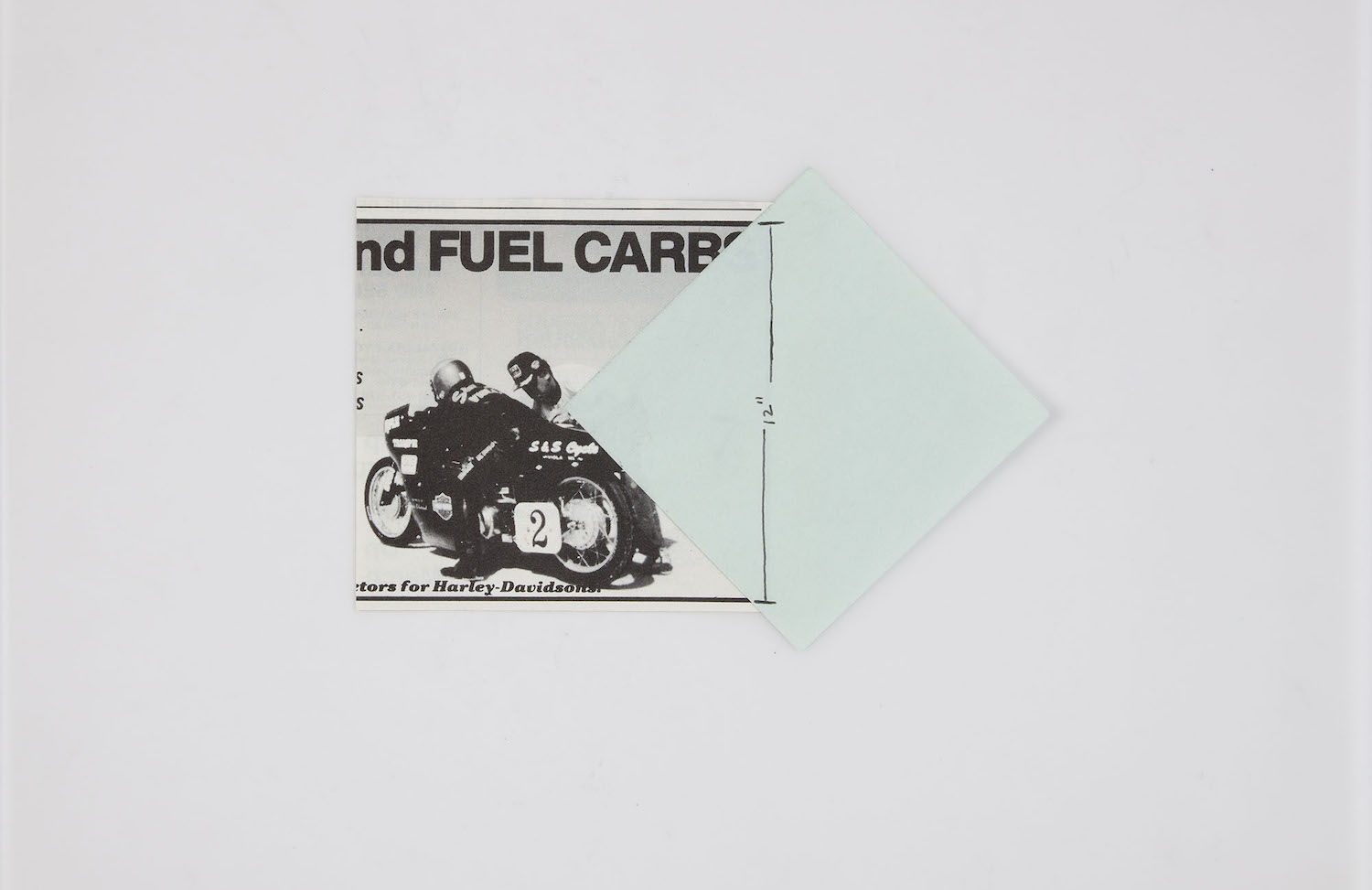

Two walls gridded with framed paper works explain this in part, as they dissolve from appearing as concretist and neo-geo, in the veins of a grayscale Max Bill, toward a revelation of unique nature. One small drawing from c. 1979 creates angular compositions out of a gender-neutral display of bondage. It imbues a sexual and violent duality into the dozen organically abstract spray enamel on vellum pieces, from the 1990s, scattered throughout the show. Every fold, real and suggested, in a Parrino turns one on, as much for ideas of gentle touch as hard beating. Along with Cady Noland, his work was an initial detector that raw forms and materials convey content and feeling, as well as spatial reactions. A monochrome of the current event. Parrino managed to tackle the ideas of his artistic forefathers without reactionarily negating their achievements. In this show, Easter eggs are everywhere: from the stationary from Alu Menziken, the Swiss company that produced Donald Judd’s last decade of work, to the renegotiation of both Lucio Fontana’s cuts and Andy Warhol’s The Kiss (Bela Lugosi) (1963) in Seduction (1984). Bentoverslime #1(1995) is, in itself, a comprehensive introductory course in sculptural dialogues since 1960. Save David Reed, I can think of no other artist of his generation who so efficiently and precisely steers his work through a lucidity of influence. The discourse around Parrino typically credits him with admitting to, and then working around, painting’s apparent death in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Our current moment of that medium’s global imperialist success renders this reading whimsical and dated. It wasn’t painting Parrino was mining, but the death of the industrialist idea of modernism with its insatiable need for advancement in styles and schools of art, rather than deeper development of known ideas. As Parrino macerated movements and trends, dancing the macabre with a sleeping beauty, only appearing dead, he raised zombie hordes of ambiguity. The works here, paradoxes of meaning and execution, all try hard to not appear as they are. Concurrently pretending to be what they’re not is a clear-cut and unambiguous brilliance.