Performances of blackness have generally been limited to particular styles of music, theater, dance, and popular culture, which has fostered a historically narrow perception that black artists had a distinct status in modernism: often relegated to the realm of so-called “primitivism,” and thought to have a natural disposition toward spontaneous expression instead of thoughtful purpose or action. In the Americas, indeed wherever the specter of capitalist exploitation in relation to the estrangement, or more precisely, the overwhelming fungibility of the black being has occurred, the “body as material” for a black artist has been overwhelmed with historical meaning and scopic regimes, as well as laden with signifiers and markers that are deeply related to historical narratives. In such a context, artists engaging the conceptual dimensions of racial blackness, which is to say the very system and structures through which the concept of race developed, circulates, and is sustained, have evolved formal techniques and aesthetic operations that challenge legibility, rely upon opacity, and proceed by errancy.

In many instances, black representation involved the confluence of an artist’s individual perspective or desire for personal agency with the discourse of racial advancement movements (historically including the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movements in Britain and the United States, Négritude in francophone Africa and the Caribbean, and the art of nascent post-apartheid South Africa), circumscribing the parameters of blackness in art. There has been a tendency toward figuration and realism in most of these movements, which have operated on principles of an impossible transparency, immediacy, authority, and authenticity. These well-meaning efforts ultimately reinforced a reductive notion of “black art” or the idea of an essence locatable in works of art by black artists.

Over time, artists’ responses have been to create methodologies and concepts as strategic calculations in opposition to and as aversions to regimes of representation in both intraracial and general discourses. In these instances, the aesthetics of dematerialization have been useful. In performance, artists summon a “body,” yet through aesthetic tactics attempt to alleviate its historical and social weightedness by acknowledging particular histories and social conditions, while simultaneously expressing a desire to maneuver, circumnavigate, and reimagine them.

In the wake of debates about and movements dedicated to the subject of black representation, artists have turned to a vector of opacity in which their works operate and treasure above all else what can be described as a productive withholding. This inclination can be understood as a catalyst toward dematerializing social structures at the level of the individual, and thereby coming to know oneself in the larger social schema. What remains after such a process is a stark reminder of the vitality of the unrepresentable, the indiscernible, the elusive, and all that is deficient at the level of the visible. In performance in recent years, black artists have made black works with their black bodies in places of literal or metaphorical darkness; typical modes of signifying are thus obliterated. Primarily interdisciplinary, total works of art with visual art, dance, language, the projected image, and sound elements in equal measure have emerged from experimental scenes in which opacity, obfuscation, and darkness are tactics, strategies, and modes of blackness as artistic resistance.

Stanley Brouwn is a progenitor of such a sensibility, if one is to be had. Eschewing the circulation of biographical data, images of himself, and reproductions of artworks, he takes an approach to Conceptual art that can be distinguished from that of his peers precisely because it situates Conceptualism’s key characteristic — dematerialization — not only in the art object but elsewhere and otherwise. His art is the embodiment of the colonial bureaucratic administration: the conceptualization, itemization, enumeration, and adherence to a set of tactics structured for the embodiment and therefore expression of operations, procedures, supervision, rules, regulation, control, and management. For example, such a proclivity manifests in This Way Brouwn, begun in 1960 in Amsterdam, which involves the peripatetic artist strolling the streets and randomly approaching people and “ask[ing] anonymous passersby to draw on a sheet of paper directions to a particular unnamed location”; he would then apply to the drawing an eponymous stamp.[1] It also is present in the gray metal file cabinets housing the cards that in part comprise The Total Number of My Steps, a perambulant piece initiated in 1971 in which the number of footsteps Brouwn takes in twenty-one cities is enumerated and displayed. Brouwn also had a series of works in which he would use his body as an individualized unit of measure or would turn to archaic ones no longer in use, such as the Egyptian cubit, Castilian pie, Western European ell, and Hispanic vara. Often these works demonstrate a preoccupation with distance — being away or approximate to something other than where one currently is. They also emphasize the truth of fluctuation, irregularity, and variation as things to be valued, against conformity and universalism.

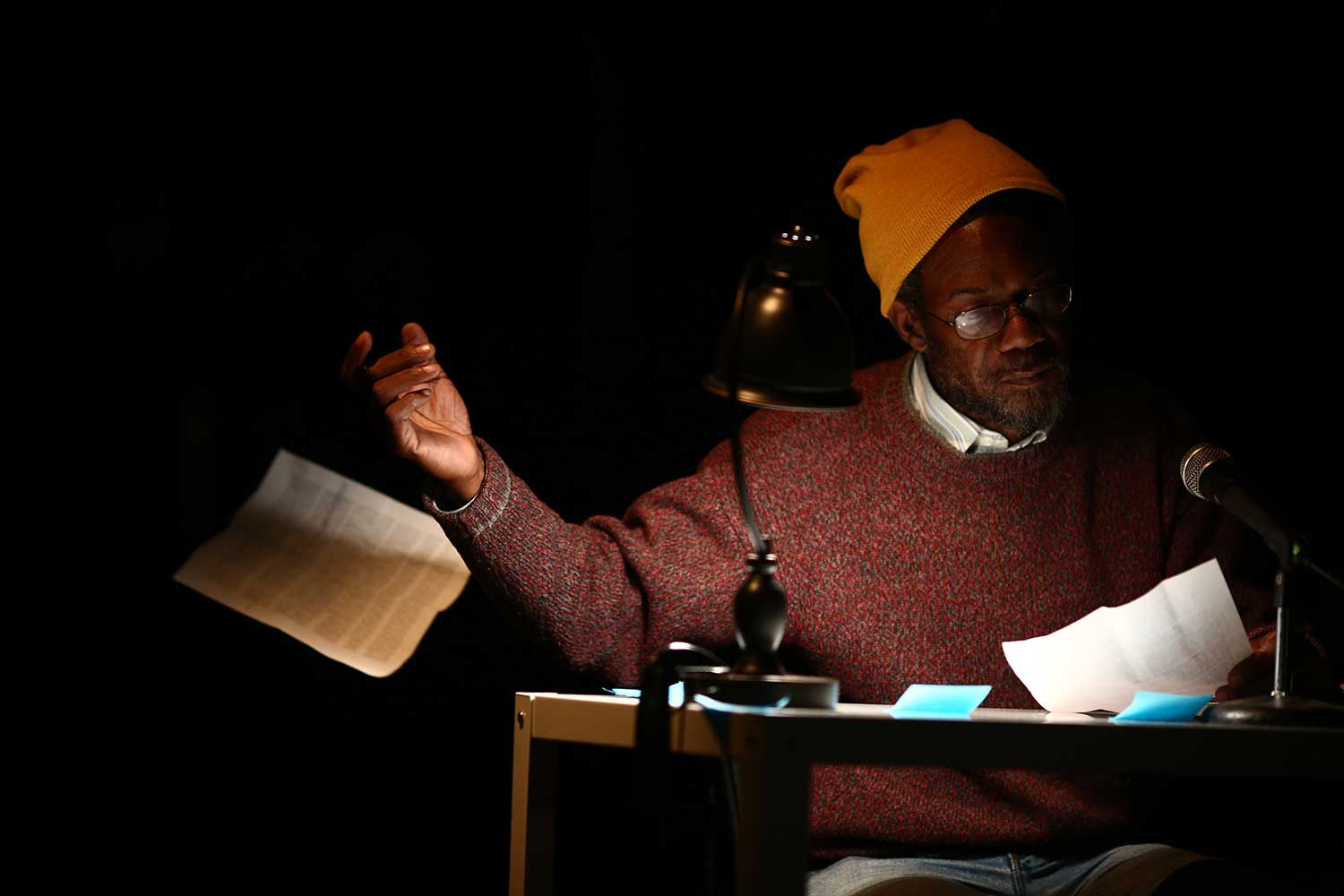

Though perhaps best known for his street crawls such as The Great White Way, 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street (2001–2009) and public performances like Thunderbird Immolation (1978), Pope.L’s Cage Unrequited (2013) engaged a similar desire for encounters with operations of chance and anonymity. It was staged in a black-box theater illuminated by only a few clusters of celebration lights and a desk lamp; their minimal light dissipated into the vast darkness of the venue, a void with almost no audience. Over the course of twenty-five hours, a procession of some seventy-five artists, scholars, musicians, students, and curators — also the performance’s only viewers — took turns reading portions of John Cage’s Silence: Lectures and Writings (1961) in twenty-minute intervals. Around midnight, Pope.L’s interlude involved a talk about Julius Eastman, a black gay avant-garde composer, who had a vexed relationship to Cage and ultimately fell into terrible obscurity: Eastman once staged a performance of Cage’s Song Books (1970) in which he undressed his boyfriend and attempted to disrobe his sister. Pope. L’s act of homage to such a transgressive composer as Eastman thus also took on the tone of a critical, antagonistic act of filial (im-)piety. This was surprisingly accentuated when, in the predawn hours, the lobby was unexpectedly occupied by two bands from the Black Rock Coalition. The sudden proximity of reading about silence and Afropunk music is a sublime example of the contrary dimensions of black matter.

Brouwn and Pope. L’s art, primarily shown and contextualized in the visual arts, would presage a sensibility materialized by subsequent generations of black artists. Beginning in the late 1990s, artists such as Ellen Gallagher, Glenn Ligon, Steve McQueen, and later Adam Pendleton, Rashid Johnson, Oscar Murillo, and Torkwase Dyson, among others, turned to black monochromatic painting and objects as an attempt to negotiate and exhaust the paradigm of black representation in visual art with profound capaciousness and theatricality.[2]

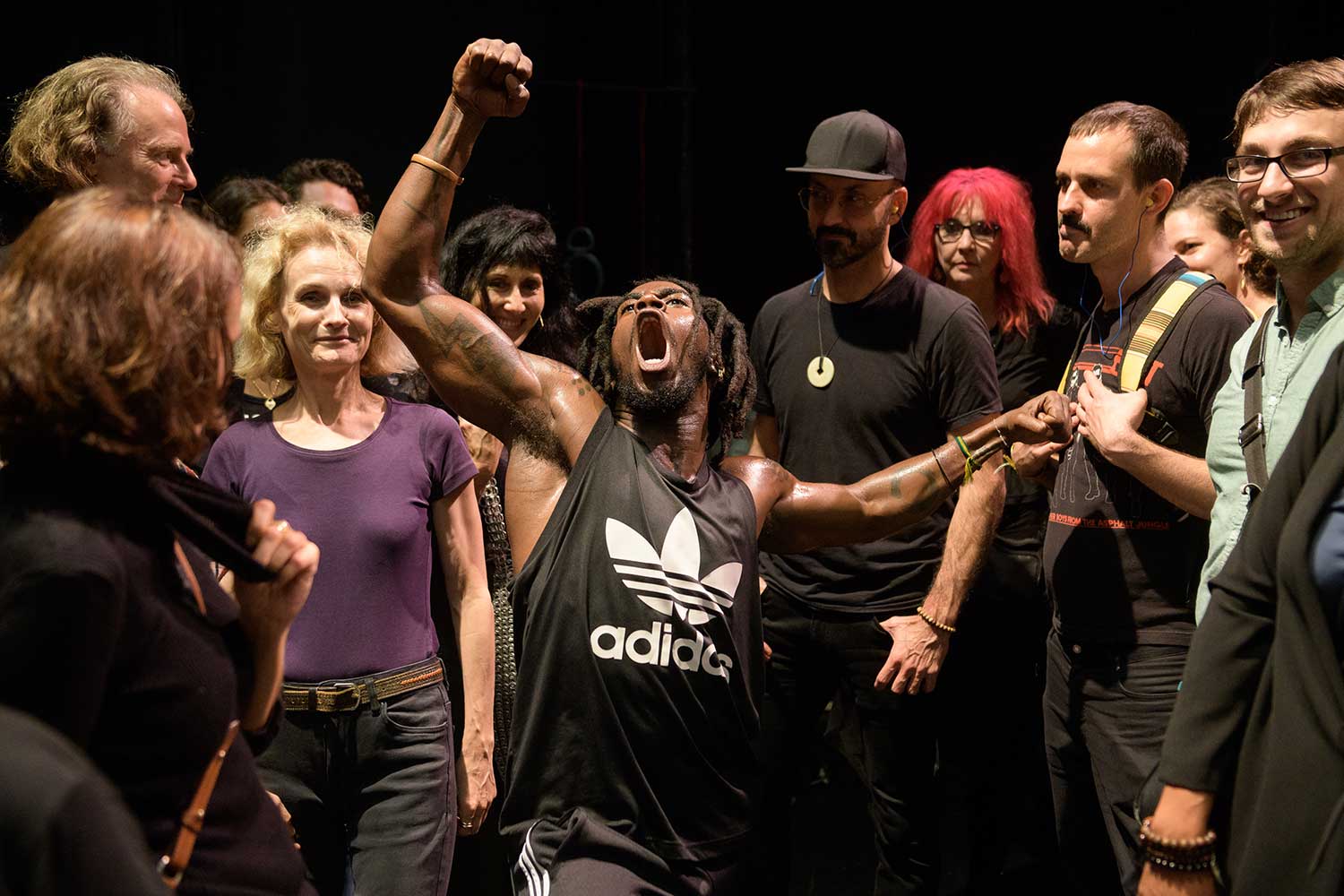

In actual theaters, artists such as Nora Chipaumire, Okwui Okpokwasili, Will Rawls, and Claudia Rankine have made dark dances interrogating the uncanny realities and aesthetic potential of blackness. Chipaumire’s choreographic operations explore the bounds of virtuosity through modes of resistance with a distinct punk sensibility and gender complexity. Her more recent works have been shown in near total darkness. In 2012, with Okpokwasili, she choreographed and performed Miriam, a dance of a personal exploration considering the antagonistic relationship between public expectations and private desires of African women, and the presupposition of certain feminine ideals with which such women must contend. Portrait of Myself as My Father (2016) played with illuminations and shadows to structure the viewer’s experience of power, masculinity, and sexuality. #PUNK 100% POP*NIGGA (2018) has almost no “dancing” at all — just dub beats, growls, verbal stutters, and somatic swerves, all in repetition.

Okpokwasili’s own interdisciplinary performances, which have similar conceptual considerations as Chipaumire’s, have played with blackness in a range of registers. In Bronx Gothic (2014), a solo tribute to black girls’ coming of age, her body is at times a mere silhouette of darkness, often with her back turned to the audience, cast against a backdrop of white fabric one of the most remarkable movements is when her entire physique trembles violently, as if needing a desperate release. Visual obfuscation is also a dominant trope in the ensemble work Poor People’s TV Room (2017), a hybrid, nonlinear piece that traverses the Nigerian black female experience from the Women’s War of 1929 to the current Bring Back Our Girls movement. Some portions of the work are performed in the dark, while in another section a thick, c loudy plastic tarp covers the width of the stage and forecloses the audience’s ability to see the performers.

Will Rawls, whose choreographic work is rooted in language and questions of subjectivity, made a black dance in 2015 with the solo Personal Effects. This evening-length work, performed in a basement, is a meditation on the constraints of identity and the precarity of black queer masculinity, as Rawls navigates the space with his back turned to the audience, diverting behind walls and into chambers not entirely accessible to viewers, turning off and manipulating the lights, stammering incoherently, and donning a hoodie sweatshirt such that he is obscured for the vast majority of the performance. What Remains (2017), a collaboration between Rawls and poet Claudia Rankine, is an artistic outgrowth of Personal Effects, although an ensemble work. It concerns surveillance of black bodies, expressing articulations of the frustration that results from such optical oppression and dominance. It draws upon Rankin’s stellar poesy on being black in America — her books Citizen: An American Lyric (2014) and Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (2004) are fragmented, reassembled, and distended with and by movement and voice, including pop hits like Jidenna’s “Classic Man” (2015) with its refrain “even if she go away…” The work is also informed by Homi K. Bhabha’s essay “Writing the Void,” published in Artforum in the summer of 2016. A highly structured improvisation, the work attempts be a “void,” or what Rankin has described as an “already dead space,” as mimetic of lived blackness in the United States and understood as full of potential and possibilities despite its seeming lack. Staged in a dark, bare setting, the performance features lighting used sparingly as if to emphasize the tenebrosity of the space and the bodies performing in it. The sense of “shadiness,” which is to say suspicion, that attends all stereotypes of black beings is materialized as performance as image-making, as a way of manipulating visibility and speech precisely through and as a basis of recalibrating value.

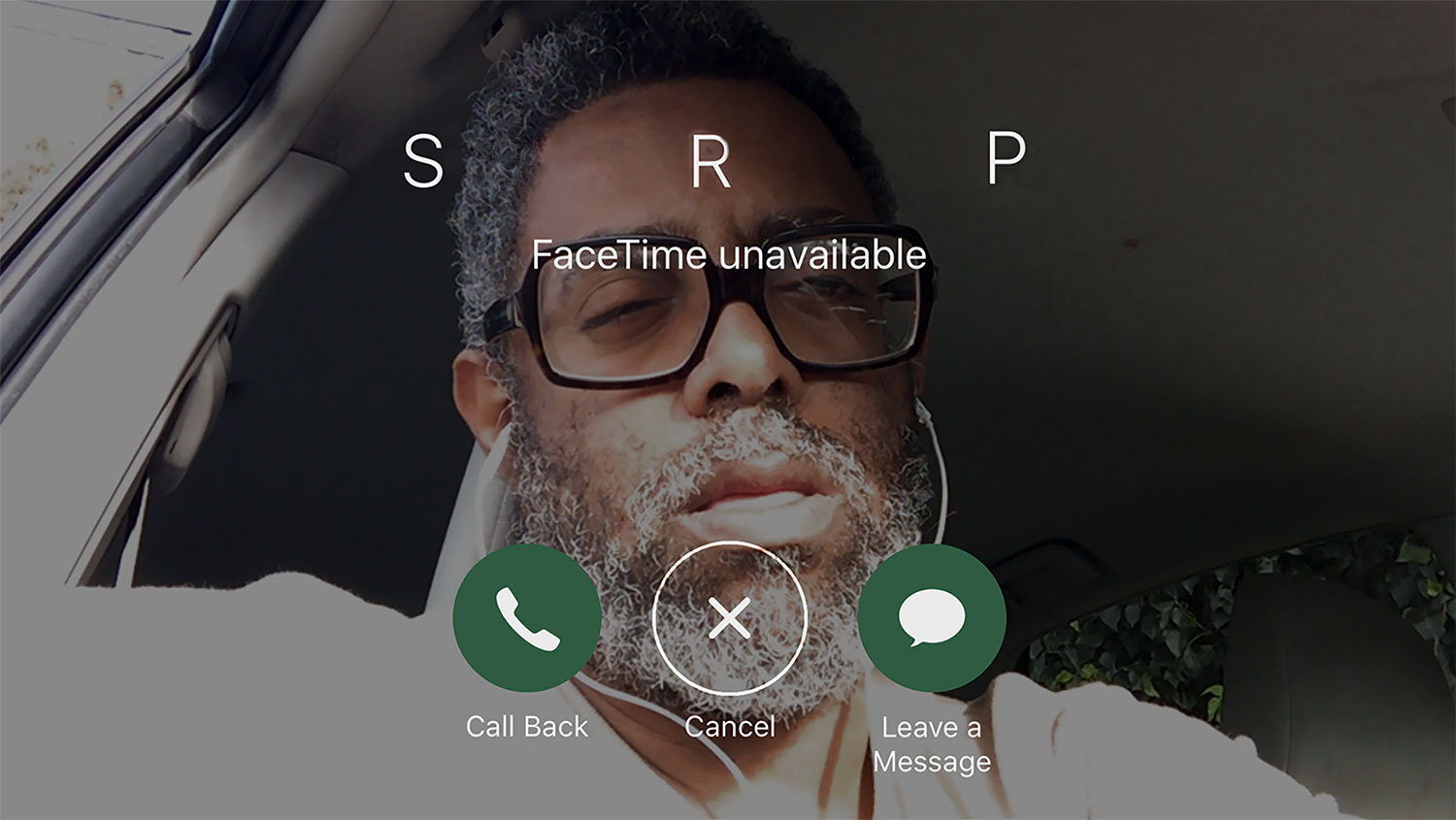

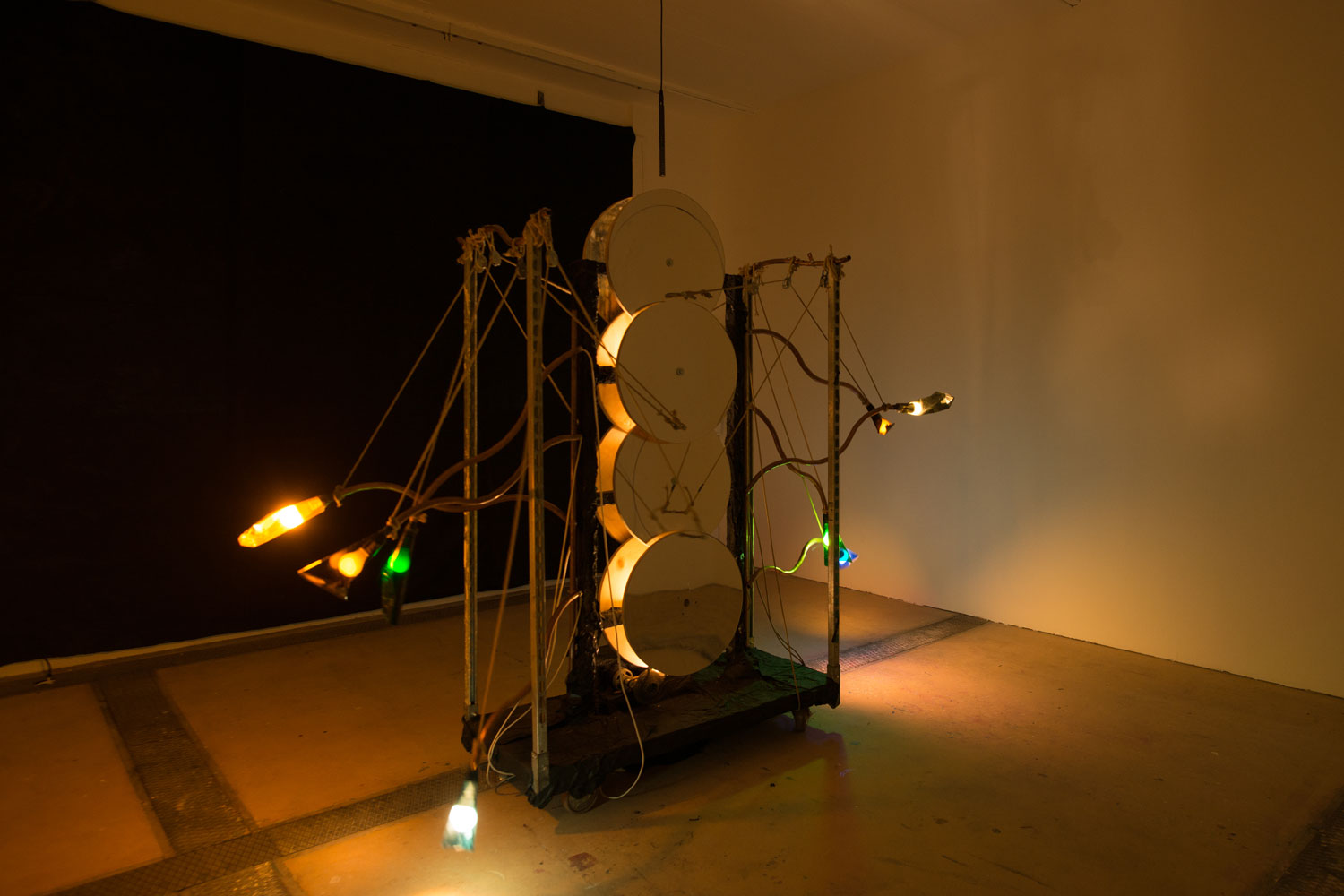

Kevin Beasley’s sound works are made on turntables, as in I Want My Spot Back, a performance in three parts. The first version occurred in 2011while Beasley was a graduate student at Yale University; he performed in a room within a room, a white box with internal black walls located in the basement of the art school’s sculpture building. Another iteration took place in the sanctuary of St. Mark’s Church in New York’s East Village as part of its Platform 2012 Parallels program, culminating a day of overlapping performances organized by Ralph Lemon. Before Beasley finished his set, Ishmael Houston-Jones was rolled onto the floor and totally enveloped and bound in black plastic bags while reading Ralph Ellison’s generative Invisible Man (1952). This was reminiscent of Houston-Jones’s 1984 dance f/i/s/s/i/o/n/i/n/g, performed at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York, upon his return from the civil war in Nicaragua — a work he performed wearing only work boots, socks, and a bandana to veil his face. Lastly, Beasley took to the turntables at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (also in 2012), where he overwhelmed the audience with sonic scats and scratches, laced with tempting hip hop beats cut and looped with maddening intensity to undermine any sense of gratification. In each instance, deafeningly loud vibrations shook the room and altered one’s sense of orientation. Beasley isolates these dubbed beats into single frequencies, notes, or keys that appear as hundreds or even thousands of dashes, which collectively constitute a cartography of song as a new plane. His microscopic extractions and condensations are extremely reduced, isolated elements of sound waves, played at tremendous volume, which confer a physicality that renders a powerful somatic experience. Beasley builds his own subwoofers and often constructs stand-alone environments in which he performs on the floor. For him, one of the most generative aspects of his sound pieces is that they are often simple manipulations of air, for sound is nothing more and nothing less than the movement of air. The paradoxically ephemeral yet physical nature of such sound work is a hyper-distillation of music that strips it of all of its leaden capitalistic and materialistic references, reducing it to an anti-rhythmic primordial essence that is sheer affect in a raucous void. Most recently, for his Whitney Museum exhibition titled “A View of a Landscape” (2018), Beasley made a sculpture-instrument out of a modular synthesizer that connects up to twelve microphones in a chamber that houses a cotton gin motor from Maplesville, Alabama, which transmits the incessant hum of the machine into an adjacent listening room. In a related performance held in January, Beasley and Taja Cheek made cacophonous electronica with their laboring machines. At one point, near the end of the approximately hour-and-forty-minute set, Beasley animatedly banged away on a lone cymbal, only we couldn’t hear a single note from it. The noise from the machines killed the beat and disjoined what we saw from what we heard in a sweeping act of total disembodiment.

In New York at the moment, a concentration of artists is taking the notion of dematerialization in art at the nexus of identity and social reality to the extreme. Devin Kenny is annihilating rhythm to achieve stretched, condensed, and reconstituted sonic elements appropriated from trap music that interfaces and reverberates with his own socially conscious lyrics. Thickening the sound, he scours the internet and social media for source material that he places in dissonant juxtapositions. Meanwhile, at Performance Space this past fall, American Artist, Caitlin Cherry, Nora N. Khan, and Sondra Perry exhibited a similar nihilism as they imagined the end of the world with their installation A Wild Ass Beyond: ApocalypseRN, a black shack on wheels and in total disarray. The work asks how the reality of blackness as lived social death[3] has shaped those given to it, and are therefore susceptible to police violence, economic precarity, and dreams deferred until the end of days. They seek a new maximal language, baroque iconography, and an affectionate way of being in the world and with themselves. Such a desire for intimacy is also expressed in niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa’s Black Power Naps, a roaming live installation, also recently mounted at Performance Space, that critiques capitalism and neoliberalism and exists to provide no entertainment. Because of the history of enslavement, extraction from and exploitation of subjugated people has led to an epidemic of restlessness and exhaustion that instead necessitates rest, relaxation, and downtime as the event.

These artists’ performances propose alternative types of representation through various modes of dissonance. In their own distinct ways, each summons a blackness in search of its own event horizon, an absolute void, a total darkness that is not nothing — which is to say not a single thing[4] but perhaps, maybe, likely a multitude constituted in and through chance, chaos, noise, a stutter, a fragment. These artists evince modes of illegibility, withholding, and opacity that conjure an extreme abstraction, for which there are myriad approaches and styles. When sieved, they are expressions of capacities to delight the imagination.