Designers of technology love to propagate the myth of a just world, in which people always get what they deserve.

In erasing the messier and unsolvable elements of social experience that shape subjecthood, technology attempts to frame us as clean and uncomplicated. We become reducible, mapped by a programmable sets of traits with defined, singular meanings. Our digital choices and consumption patterns give a portrait of who we are. We are easily represented by our avatars.

It is cheaper to be a universalist, disavowing structural inequities, abuses of power, the ubiquity of classism, racism, and misogyny. It is easier, traditional, even, to just ignore what we cannot see: trauma, depression, mental illness, chronic pain. It is less agonizing to ignore how environment or oppression or historical lack of opportunities, “factors” that cannot be hacked, reworked, or re-engineered, close doors.

In her video piece Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016) Sondra Perry subtly interrogates and undoes these pervasive technological claims about our ontological position, and our being in the world, stitched into the programs, interfaces, and systems that dominate and organize our lives. Last fall, Graft and Ash was part of several video installations within Perry’s first solo institutional show, “Resident Evil,” at The Kitchen, New York. The piece was split across three LCD monitors that were retrofitted atop a bike workstation, painted in electric blue automotive paint.

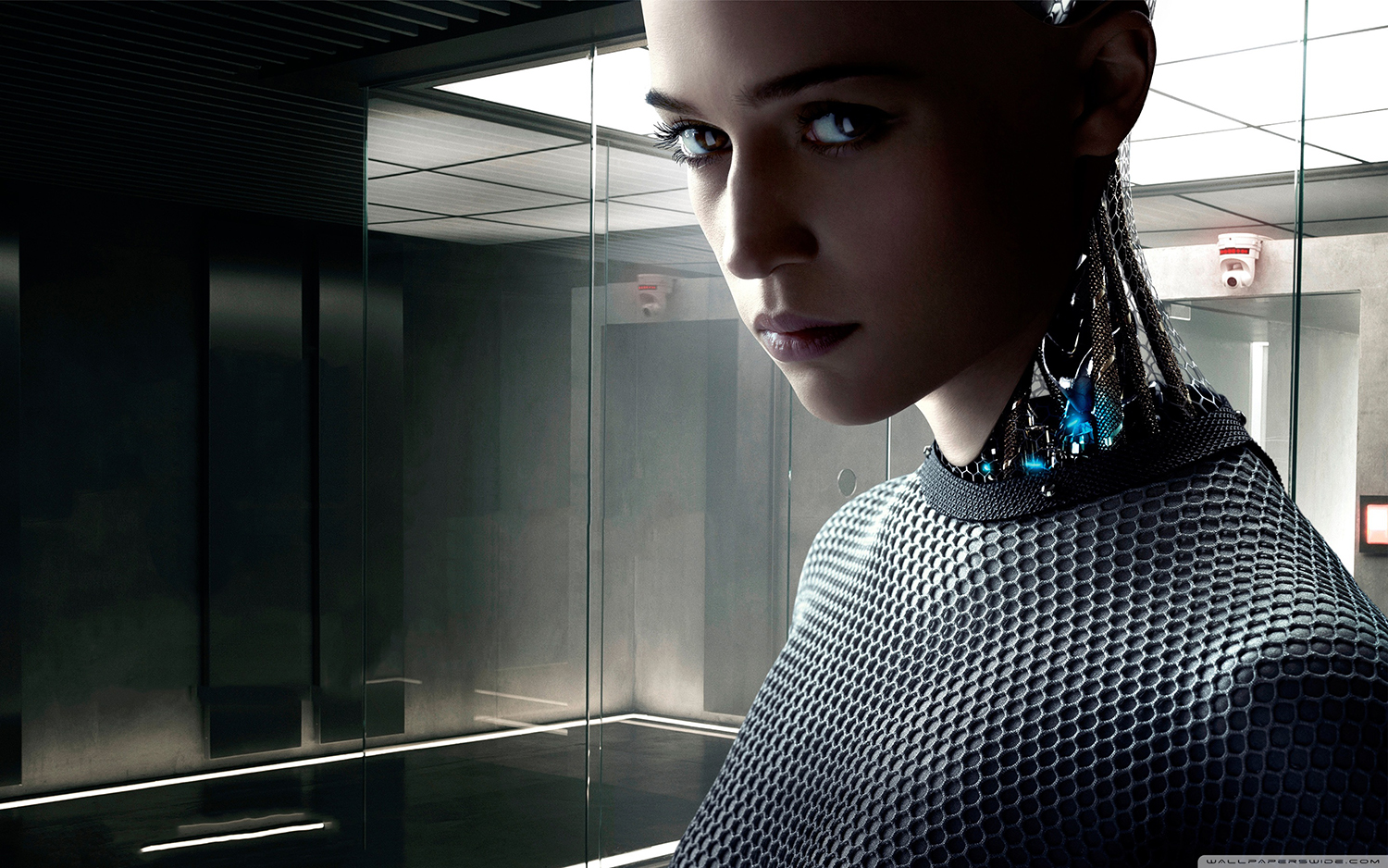

Fading in, Sondra Perry’s avatar, her face stretched atop a speaking face template, begins to speak. She hovers before an alternating backdrop of Chroma Blue (used in blue screen animation and special effect rendering) and a close up of Perry’s own undulating skin surface in 3D (so detailed it seems to be a surging sea of gold and red and pink). She first intones the details of what we are seeing: the make of the bike workstation, the hexadecimal code of its Pantone paint, the monitor set-up, the Ocean Chill out Music for Relaxation / Meditation / Wellness / Yoga Youtube video playing in the background. Her expression is bemused and warm, searching and curious, looking down at and, it feels, deep into us. The head lolls from side to side, much as we look at ourselves in our front-facing phone cameras. Her voice is relaxing, but still performatively artificial. The viewer relaxes and is primed to be soothed.

“We’re the second version of ourselves that we know of,” she opens, her face captured from Sondra’s image, “rendered to her fullest ability,” with limits, as she “could not replicate her fatness in the software that was used to make us.” This instant friction suggests a body living off camera, off screen, forced to exist in a system that does not acknowledge one’s form as a valid type to be represented. Further, standardization of a neutral, normal, good body is ever a reflection of a dominant cultural standard; all these standards end up in code. People using these programs internalize what is neutral, and what is deviation.

That AI is not neutral, objective, or devoid of values is finally gaining widespread traction into debates about the future of AI. Perry here crucially uses AI or rather, its simulation, as a laboratory for mapping out how race and body politics are woefully mechanized. She frames technology as it allows us to dehumanize one another yet again, flattening race history and political context out in favor of a spectrum of slottable “markers” like age, class, and education.[1]

Frequently, the algorithm’s decisions are not mysterious or beautiful, but quite banal, familiar, a tool and platform for reifying inequity. That AI can now make decisions of horrifying and binding effect (who gets a job, a house, insurance), potentially locking people deeper into structural inequity, it seems imperative we question the pure, mathematical objectivity claimed by engineers who also deny white supremacy’s fundamental relationship to capitalism.

In a nine-minute performance, we learn the detailed contours of Perry’s disembodied representation. Ambient, in the background, is the unseen body, both Perry’s and the black body, generally. The avatar changes tone, clear and measured though still pleasantly neutral: did we know, she asks, that attributing success to personal characteristics instead of biased structural systems has a negative impact on the health of black people? People who “both strongly believed that the world was a just place and experienced higher rates of discrimination were more likely to experience higher blood pressure,” chronic illness, and early deaths.

What does it mean for an avatar to ask us to contend with the persistent social fallacy that trauma and oppression are not legible or real? Perry’s face does not quite fit atop the avatar template, so pieces of the substructure, the wireframe, peek through. A second eyelid glimmers at the edge of her eyes, so the effect of an uncanny mask is constant. The center, the structure, does not hold.

The avatar has slips in its “elaborate performance,” which all minorities must implicitly deploy in a racialized society. Some reviews of the exhibition suggest that the avatar “malfunctions” to tell us how it really feels: “Exhausted … daily, with you n****s all up in our fucking face.” But the breaks are intentional, revealing exactly what is on its creator’s mind. The viewer is turned to remember that these “mistakes in performance” are not shown often in real life, for fear of social retribution. Perry’s avatar notes, wryly, “We are not as helpful or Caucasian as we sound,” marking the exhaustive labor and burden of such performances.

Perry’s avatar cleverly and obliquely reveals how limited our collective imagining of the interiority of others is, by centering hidden feeling, hidden sickness. “Productivity is painful and we haven’t been feeling well,” she says. She is told she should live up to her potential, but “We have no safe mode,” she adds; existing in the world is a matter of constant risk. How to make this risk continuously legible? As in many of her works, Perry suggests a kind of brief respite in abstraction; the film cuts to a ball of her skin, rotating above a grid.

In creating a sustained contrast between who is speaking — the thrown, disembodied voice — and the violence of what is being described — erasure and denial of hidden psychological suffering — the avatar forces us to think about what we cannot see. She also makes us consider what self-care cannot heal. Facials, candles and self-soothing subbass sets on Youtube might soothe traumatic shocks, but it will take more to correct the demand to be a right and good body, meaning, smaller, sweeter, never-exhausted, chipper, light in tone, and lighter. “We are a problem to be fixed, and if we resist that problem, we will be made a problem to be fixed,” she concludes.

She doesn’t assume that the listener is complicit in these structures, asking, “How many jobs do you have? How is your body? How does your body feel inside of us?” The viewer then considers how her own body registers inside of these systems, inside of software, if at all. This is a strong embodied critique of industries that try to engineer good health through self-care. It is an even broader indictment of the core of both neoliberal ideology and conservative politics, which absents institutions, society, of responsibility for anti-black racism, police brutality, and mass incarceration, and demands victims carry their pain as a fated curse, a mark of their own moral failing, ever irredeemable.