Udo Kittelmann: What are your most important influences?

Rudolf Stingel: *1

Massimiliano Gioni: You often spoke about an exhibition by Franz Gertsch you saw in Vienna many years ago and how it influenced you. Who are the heroes of your formative years?

RS: *2

Massimiliano Gioni: Do you remember when you decided that painting could end up under your feet and become a carpet?

RS: In 1989 I rented the former showroom of “Magic Carpet” on Houston Street as a studio. There was wall-to-wall carpet covering the entire floor of the loft space. John Currin and the Landers brothers were upstairs. It took me a while but at some point I realized that taking an entire space by laying carpet was more powerful than the paintings I was doing at that time.

The first time I showed it was in a group show curated by Colin de Land in the foyer of a small theater on Walker Street. In addition to the carpet I had painted the baseboards the way I did my abstract work following the instructions.*3

Jeanette Pacher: Your book Instructions is a DIY-guide about how to make an abstract painting the way you do. This rather matter-of-fact approach towards the production of contemporary art seems to ironize the (market-driven) idealization of the artist genius while it emphasizes the aspect of craftsmanship and use of everyday materials. For the production (e.g. of ornamental reliefs) you rely on the mastership of highly professionalized craft businesses as partners. Where do you draw the line (could it be reproduction/seriality?) and what meaning does craftsmanship have for your?

RS: I am by far not the first one questioning the “fairy tale of the creativity of the artist.” It derived first and foremost from a feeling of honesty towards myself. The “instructions” were a guide to calculate chance as a working method.

Helena Kontova: Is there a relationship between the self-portraits and objects from the past that you represent in your work? Which historical periods speak to you the most?

RS: *4

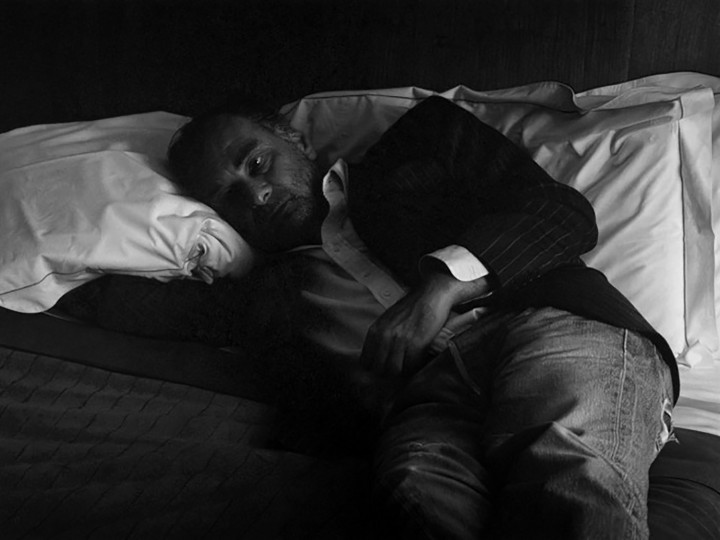

Sadie Coles: What prompted you to return to photorealist painting after a long period away from it?

RS: Unhappiness.

Giancarlo Politi: What have you found to be the difference between the Italian and American art systems?

RS: I am not aware of an Italian art system. And if there were one it would be crazy to waste your time on conquering it.

Chrissie Iles: Why is it that painting is stronger than ever in our current technologically dominated, image-saturated culture?

RS: I guess because it is the opposite of it.

Patrick Steffen: You once said that Michael Asher has had a big influence on your work, especially “where sometimes you don’t even notice that he’s done anything.” Are you (still) interested in the idea of disappearing through art?

RS: At some point I was interested in his toughness but that was a long time ago. Gradually my interest in contemporary art has vanished and with it also Michael Asher.

Paula Cooper: Given your keen sense of the way space can inform a work, which spaces have you found most intriguing? Which ones have been challenging? Can you talk about your recent installation at Palazzo Grassi?

RS: When I was asked to do the exhibition I thought, “Shit, how are you going to do this one? How can you do a show in 28 rooms over three floors without being boring?” Since Palazzo Grassi was not a museum, a retrospective approach was out of the question. A radical intervention was the only possibility to master the building. The task was to unite the three floors with their mazy rooms to one giant installation. To cover the floors and walls with a patterned carpet would annihilate the existing architecture and create a space in which gravity and scale were abolished. The relentless onslaught of carpeted rooms would induce the viewer in a sort of trance. Once in a while a window would promise relief, but what one sees are only more patterns outside.

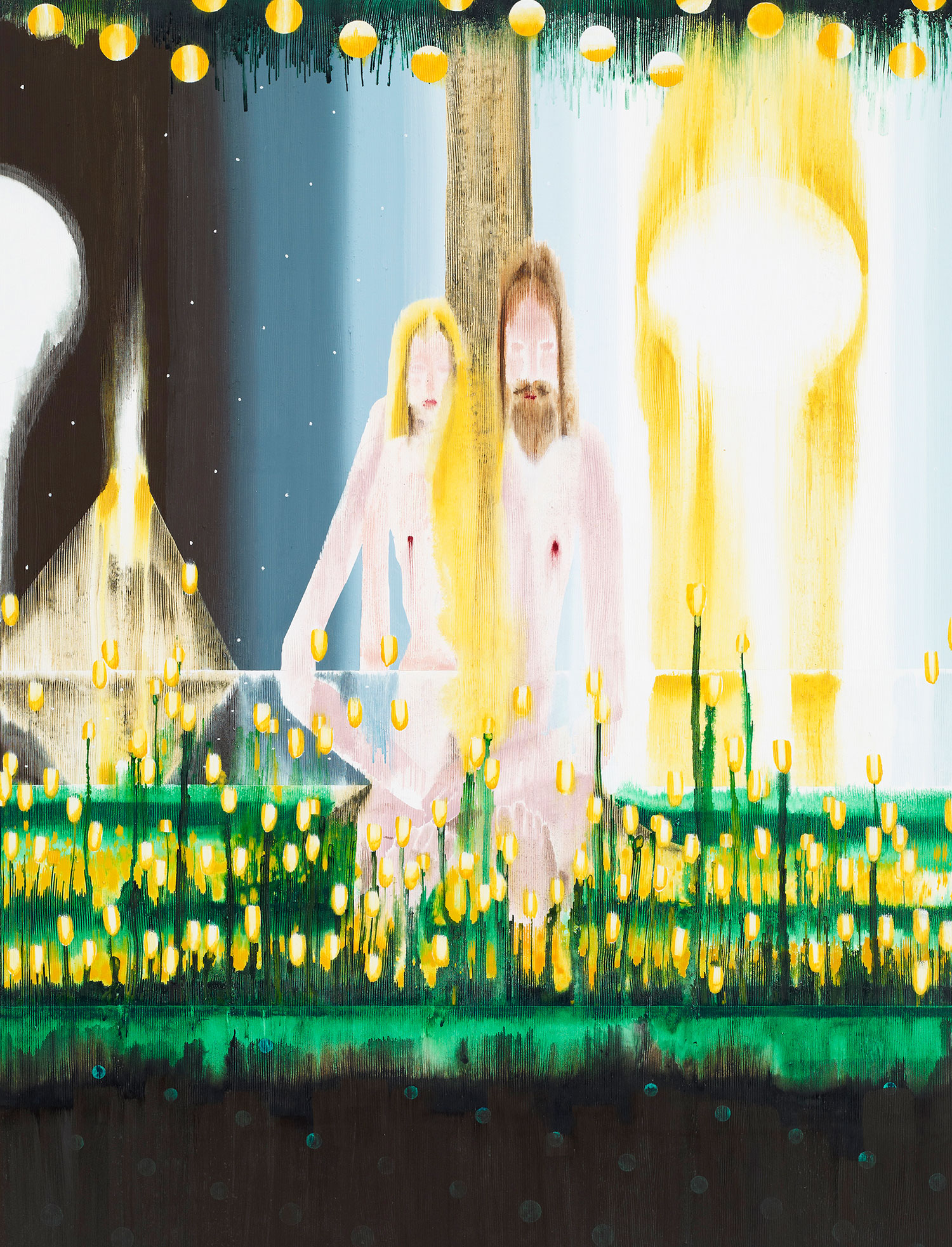

Nicola Trezzi: As part of his practice, Edvard Munch had left his paintings outdoors in all kinds of weather. I thought a lot about him when I saw the golden works you presented at Gagosian in 2011, especially since they were paired with your self-portrait, and considering how deeply your work is rooted in melancholia. I wonder if you knew about Munch’s peculiar practice — which he called “hestekur” [horse cure] — and if you see any connection with your work.

RS: Horse cures are good to get rid of a cold. I walk on my paintings because I want to hurt them.

Roberto Ago: You are one of those painters — as it could be today for Cecily Brown, Sarah Morris and Wilhelm Sasnal — who are not just painting but rather using painting to question its linguistic limits and its currency — artists like Damien Hirst, Sterling Ruby and Kerstin Brätsch. Would you agree with this distinction between two notions of painting? Would you support the leadership of artists over painters regarding their ability to innovate its specific codes as well as to interpret the Zeitgeist?

RS: Dear Roberto, I don’t know who these artists are.

Daniele Balice : What do you think your work has given to the life of a person who knows about art as well as to a person who doesn’t know about art?

RS: Daniele, if I was thinking about these things I might as well shoot myself.