Originally published in Flash Art International no. 197, November–December 1997

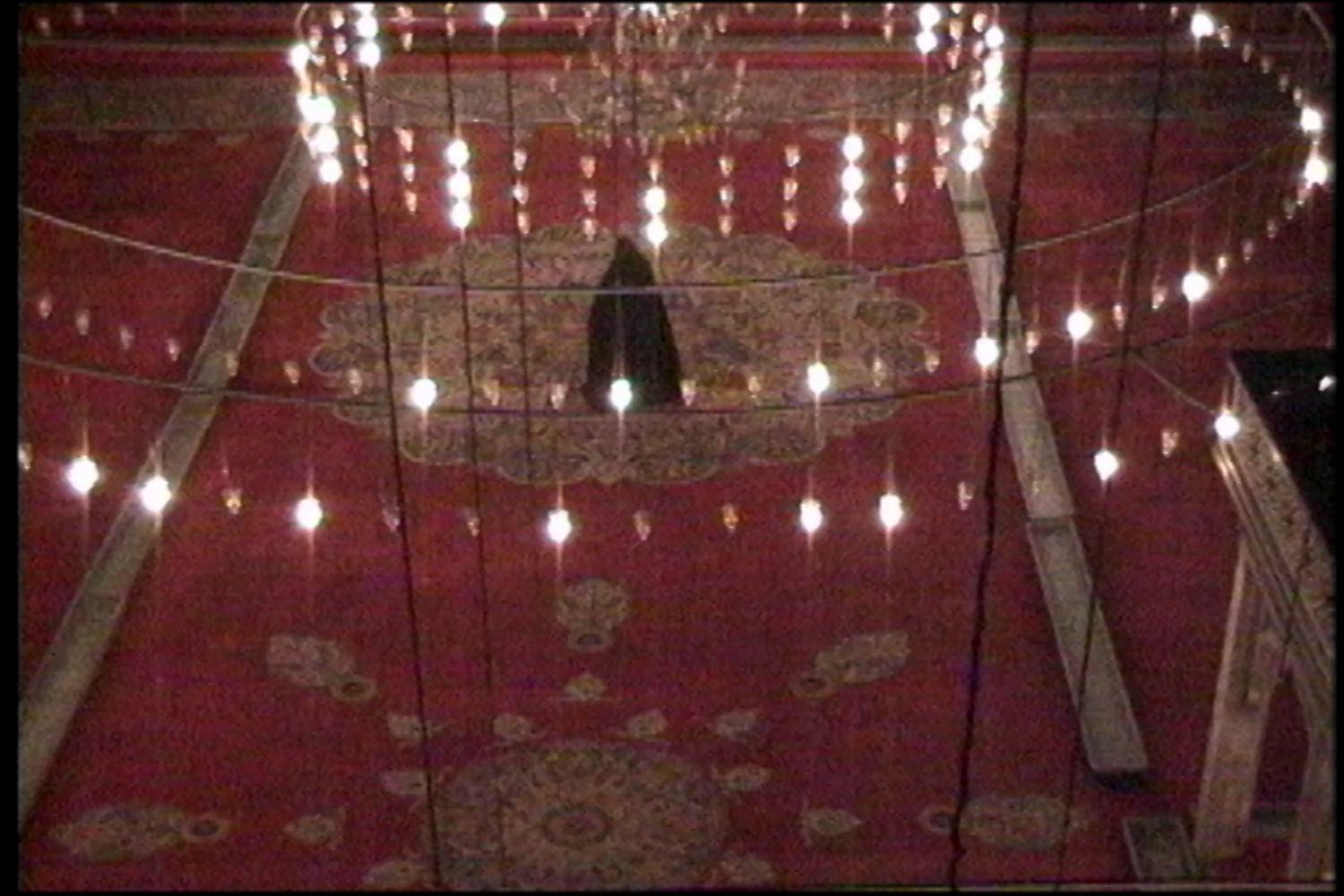

Lina Bertucci: Your work deals with very large and complex issues of Islam, women under the veil, fundamentalism, and revolutionary fervor. Tell me about your recent video installation shot in Istanbul and the meaning of the four images projected on each wall simultaneously.

Shirin Neshat: I had been working on the subject of the female body in relation to politics in Islam and the way in which a woman’s body has been a type of battleground for various kinds of rhetoric and political ideology. Recently, through some readings, I became very interested in how space and spatial boundaries are also politicized, and are designed to lift personal and individual desire from the public domain and contain it within private spaces. Ultimately, men dominate public space and women exist for the most part in private spaces, and as a woman crosses a public space she conforms by wearing a veil, hiding her body to remove all signs of sexuality and individuality from the public space. So I started to pursue some of these issues through the video.

LB: We see the figure of the veiled woman running in slow motion throughout these spaces. What does she signify?

SN: The presence of a woman’s figure, enveloped in a black chador, running against the stoic architecture of a mosque, the dense bazaar, the lonely alleyways, and abandoned ruins of a wall, speak about the peculiar relation between a Muslim woman and the spaces that she inhabits, which are so heavily coded. Each segment shows how she affects the quality of the space as she moves through it, and how the space affects her. There is a certain amount of anxiety as she moves through the spaces; it is never very clear where she is running to, or from. To me, the built architecture represents the authority and the principles of a traditional society, and she represents human nature with all its fragility.

LB: As an artist you have chosen photography as a means of representation. Why and how did you come to use photography?

SN: There are many reasons, but generally speaking, I approach photography like one would approach sculpting. I am interested in constructing images, carving monuments. In that sense, I have always felt that photography worked best with my topic and offered me a sense of realism that I needed, like the flesh and skin of a woman.

LB: How do you go about it? You set up the pictures and ask friends to take them for you?

SN: I develop the concepts, find the props and models, and hire photographers — who are often my friends — to handle the camera. We discuss the ideas at length beforehand, I make sketches of each frame as I am imagining them, then we take it from there and often improvise. I used to pose for the photos regularly, but lately, I am more comfortable in the background. I still don’t handle the camera but am able to direct the photo shoots more easily.

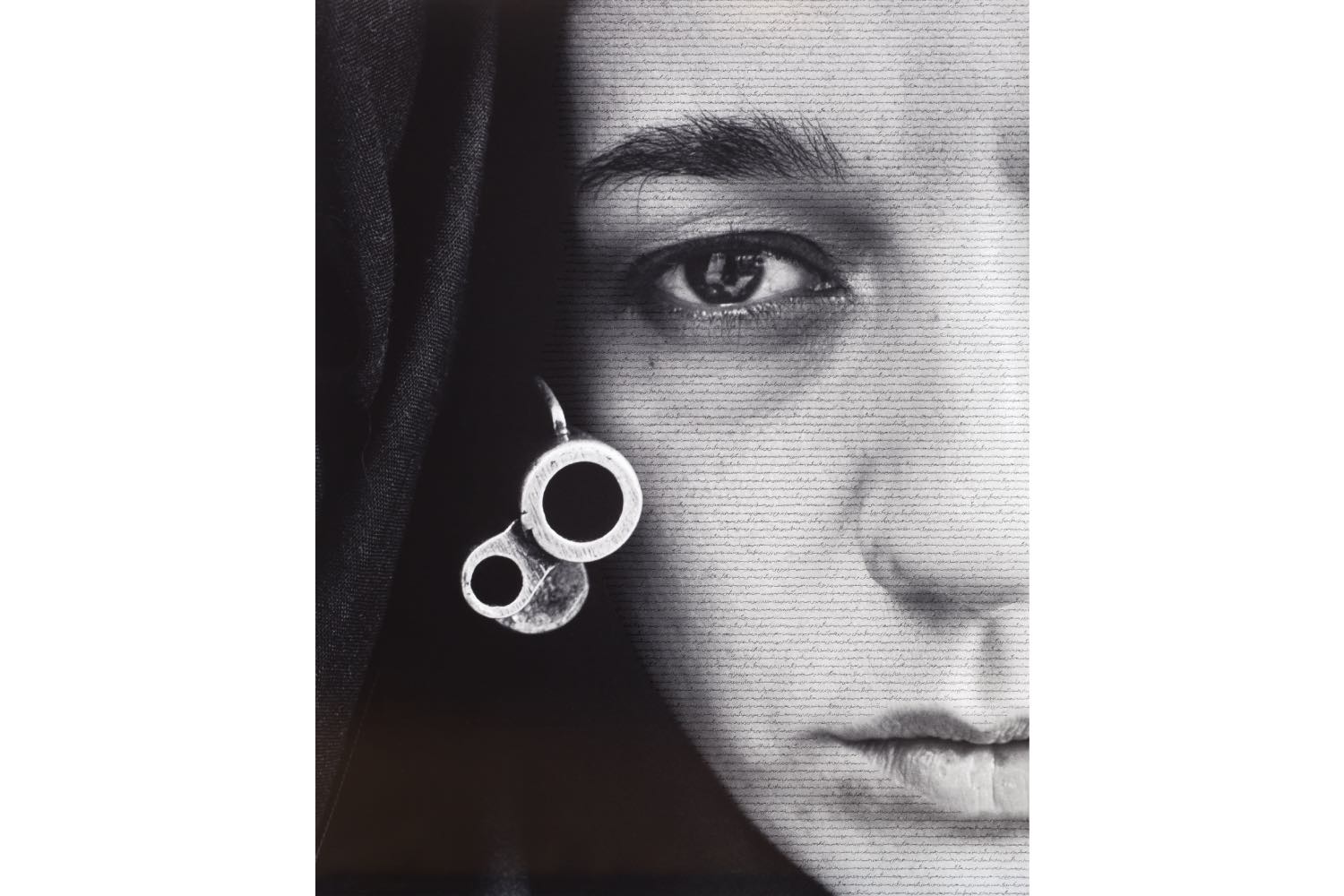

LB: In the early photographs of the women in the veil, I get the feeling that you have a double purpose. In some instances, it seems that she is exalted in the veil and relishes being in the veil; in others, it feels as if she is a prisoner in the veil. How do you feel about women in the veil?

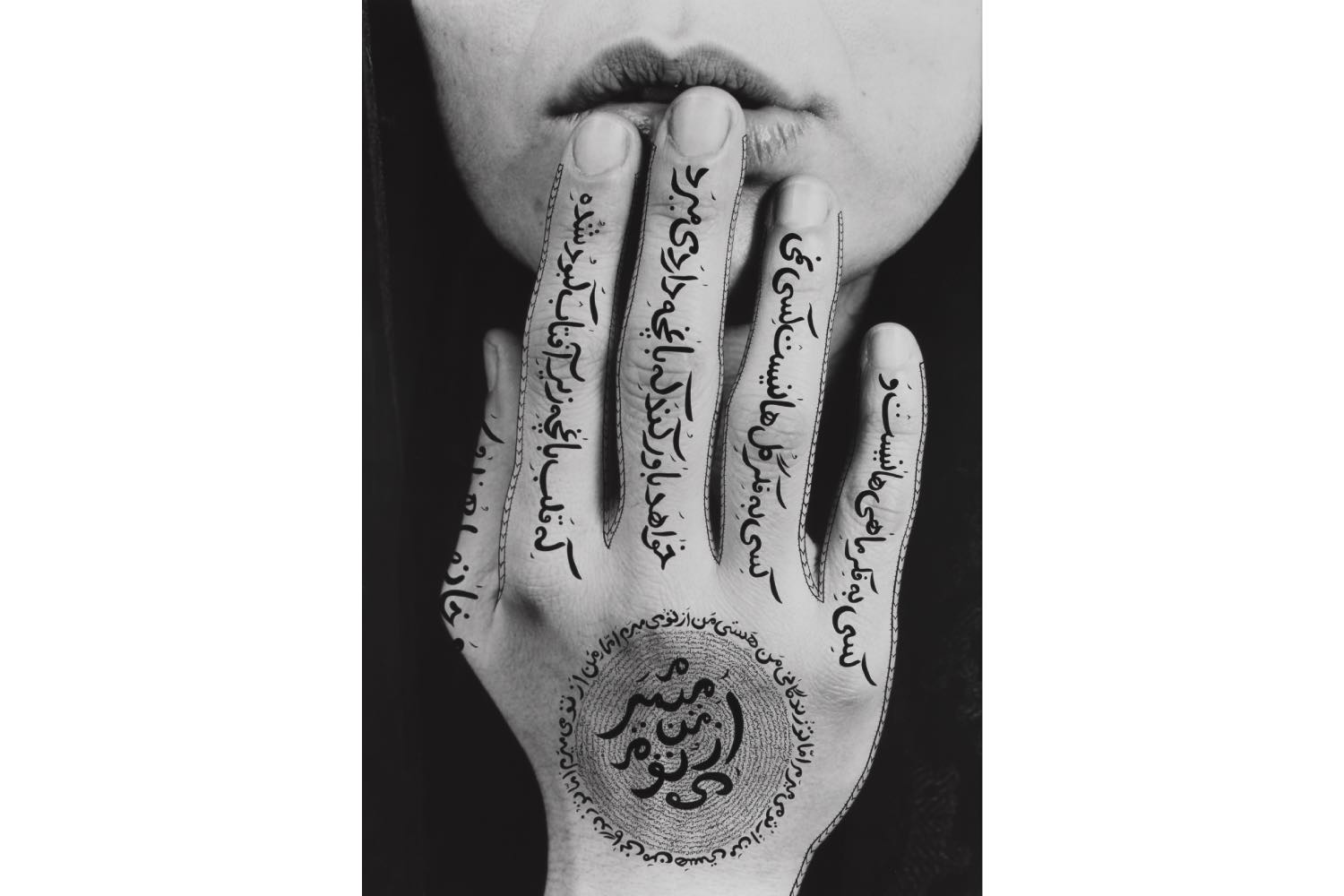

SN: From the beginning, I made a decision that this work was not going to be about me or my opinions on the subject, and that my position was going to be no position. I then put myself at a place of only asking questions but never answering them. The main question and curiosity was simply being a woman in Islam. I then decided to put the trust in the words of women who have lived and experienced the life of a woman behind a veil. So each time I inscribed a specific woman’s writings on my photographs, the work took a new direction. For example, in the first series that I did, called “Unveiling (Women of Allah )” (1993), the poems were written by Forugh Farrokhzad, a woman who felt desperately trapped in the Iranian culture and resented the male dominated structure of the society, and the writing became an outlet for these emotions and anxieties. Her poems were radical at the time, as no other woman had ever dared to speak so freely on subjects of the body, carnal pleasure, love, death, etc. On the other hand, I have taken the opposite direction and inscribed writings by those women with a strong conviction for Islam and the revolution. Their writing expresses little about their personal desires or conditions and concentrates on the collective, public interests.

Generally, this type of attitude portrays women who feel liberated by the Islamic revolution. According to them, it is only within the context of Islam that a woman is truly equal to a man, and they claim that a veil, by concealing a woman’s sexuality, prevents her from becoming an object of desire. Also, wearing a veil becomes a political statement, an expression of a woman’s solidarity with men, and a rejection of Western values. Tahereh Saffarzadeh is such a poet, and I have used her poems, particularly in the “Women of Allah” series.

LB: At what point did you decide to merge Farsi writing into the photographs?

SN: For a long time, I had been looking at Persian art and Quranic manuscripts and was very interested in the way they incorporated the image with the text. I was also struck by the tradition of tattooing in Middle Eastern and Indian cultures. For example, how for various types of festivities, women wrote on the palm of their hands. Later, when I was composing my images that dealt with the body of a Muslim woman, inscription on her skin seemed appropriate.

LB: I’d like to talk about the new photographs in the show, the centerpiece being the photograph of a man with his arms folded…

SN: For this exhibition, by bringing in the Muslim man, I wanted to open up the subject of the body in relation to gender, the male and female dynamic, and the family. Contrary to my earlier photos, these pieces intended to look at the character’s private world rather than the public one. A woman in relation to her man, her child, and ultimately, herself. With many images, I was hoping to convey the suppressed qualities of affection, desire, passion, and love that thrive to survive.

LB: How is your work received by Iranians?

SN: I think they are mixed. Some Iranians absolutely detest the Islamic government and are bitter about the Islamic revolution, so they are not so enthusiastic of any effort that tries to justify or understand it. There are others, on the other hand, who find an interesting dialogue and are happy about the way the work opens up the subject.

LB: Did you intentionally move away from guns and revolutions?

SN: Yes, because violence played no role in this subject for me.

LB: You were born and raised in Iran. How old were you when you came to the United States, and what were the circumstances?

SN: I was seventeen years old, and sent by my family to study in the United States during the Shah’s government as, at that time, there was an outpouring of Iranian students abroad. Unfortunately, soon after I arrived, there came the revolution, so I was somewhat disconnected from my family for many years.

LB: And how many years was it before you went back to Iran?

SN: The revolution happened in 1978 and I was finally able to return in 1990.

LB: What was it like to go back?

SN: It was probably one of the most shocking experiences that I have ever had. The difference between what I had remembered from the Iranian culture and what I was witnessing was enormous. The change was both frightening and exciting; I had never been in a country that was so ideologically based. Most noticeable of course was the change in people’s physical appearance and public behavior. It was a strange adjustment for me as I, too, had to put on the veil and behave like a good Muslim.

My own family had taken a big toll, as they had experienced a huge decline in their social and economic status, were cut off from all past luxuries, and had to modify their lifestyle to meet the expectations of Islamic codes. This experience really shook me up. When I came back to the United States, I became obsessed with this experience and started to travel to Iran regularly.

LB: Had you gone to art school?

SN: Yes, I did. Although, I was quite uninspired by it to the degree that once I left school, I decided to stop making art.

LB: It was not until 1993 that you started to make work?

SN: Yes. There was a period of around ten years that I made very little art.

LB: So your art developed out of a personal need to address some of these questions and issues that you were going through. Are you Islamic by religion?

SN: Although this work is not about me, unquestionably, it has evolved around my personal interest in coming to terms with the “new” Iran, to understand ideas behind Islamic fundamentalism, and to reconnect with my lost past. So as I move along and pose my questions and gather information, the work takes new directions. To answer your question about religion, I was born a Muslim but never considered myself religious. Ultimately, I think many Iranians turned to Islam prior to the revolution not as a religion, but as an authentic ideology that opposed the Shah’s regime, was sympathetic to the poor, and fought the notion of imperialism. I remember at a young age, my friends and I flirted with the idea of radicalism, and somehow identified with the position of Islam. As I left shortly before the revolution, many of my friends went on to become quite active in the process of change.

LB: The topics you are dealing with are large and complex yet the forms you use are simple, somehow minimalist. How do you get a handle on it? How do you go about constructing the images?

SN: The biggest challenge for me has been how to present my ideas in a way that avoids generalities, clichés, and a sense of didacticism. I usually first try to identify those specific points that I am interested in and find curious and critical to raise concerning my subject. Then conceptually, I compose the images with a certain amount of vagueness, almost self-contradictory, to leave the answers to my viewers. I have found the simplicity of the image is essential to give a sense of clarity within its very complex setting.

LB: You have done three major bodies of photographic work. Can you tell me about them?

SN: The first series that I made was titled “Unveiling,” in 1993, which focused on the topic of the veil in relation to the female body and the notion of the visible and the invisible. I made photos, film, and a video that dealt with that subject. All images concentrated on those parts of the body that were allowed to be seen according to Islamic regulations. There were three primary components in all of the images, which included the body, the veil, and the text. In 1994, I made the “Women of Allah” series, a group of photos that dealt with the concept of shahadat — the English translation is “martyrdom” — and presented a Muslim woman as militant, and brought up the issue of violence in relation to feminism, politics, and religion. In this series, the gun was very present in the images along with the three other components: the body, the veil, and the text. Most recently, I have concentrated on the subject of spatial and sexual boundaries in relation to Islamic politics and religious codes, which I have already talked about today.

LB: Where do you think you are going next?

SN: I like to make work that is more quiet and less confrontational in the way that it tackles traditional ideas. For the past two years, I have been concentrating on a study of a Muslim woman in relation to her religion, spirituality, and politics. Now I would like to bring the focus toward the personal and private aspects of a Muslim woman’s life. I think this approach will allow me to engage in more universal dialogues while keeping with the specificity of the Islamic culture.