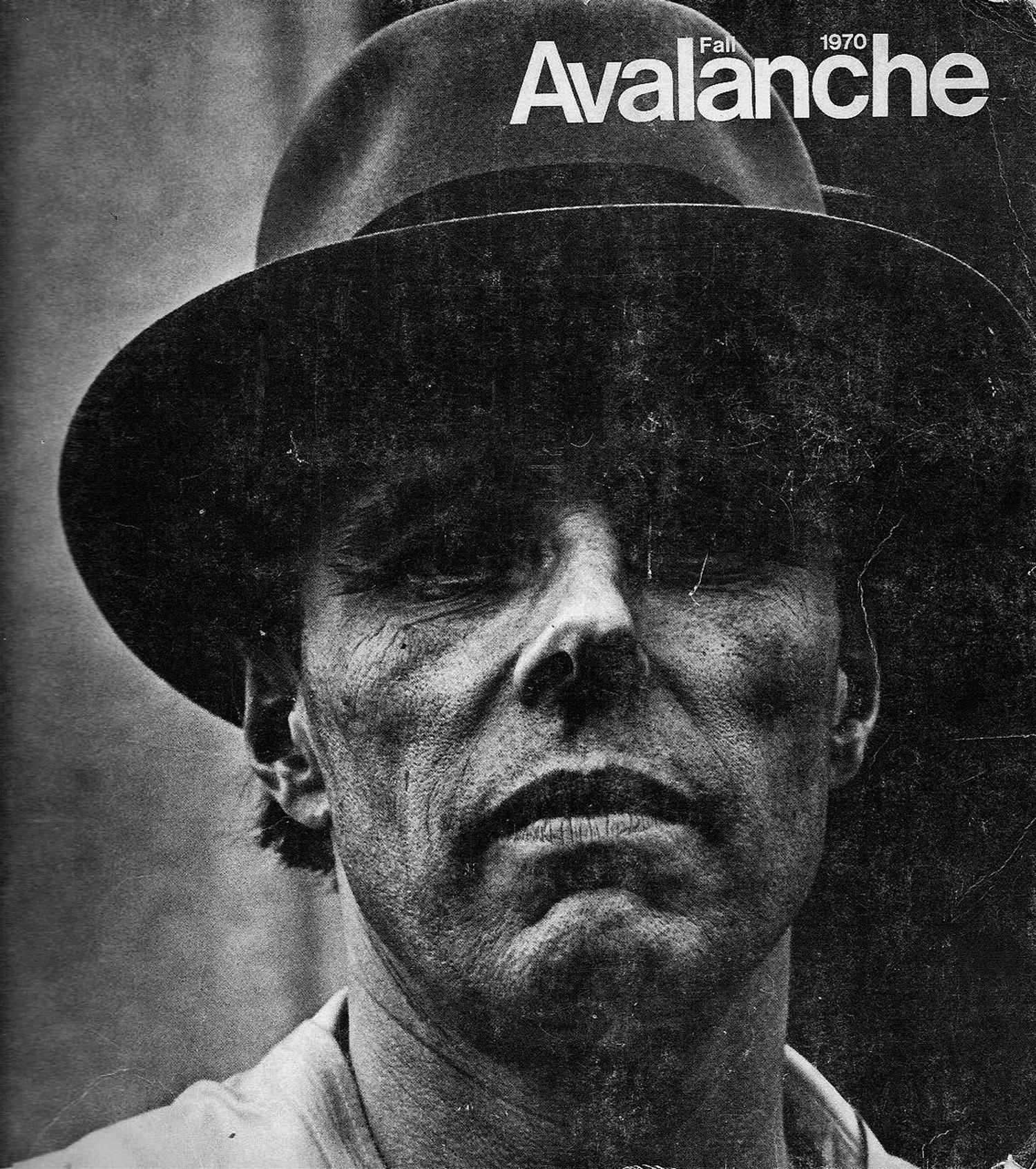

From Flash Art International No. 135 July-September 1987

Paul Taylor: I don’t remember reading any interviews with you before…

Sherrie Levine: There have been a couple.

PT: Nevertheless, somebody said to me that if artists were paid according to the amount of criticism written about them you would be a millionaire.

SL: I guess that’s true.

PT: Has there been an exceptional amount of critical attention for your work, at least in the US?

SL: I guess there has been. I’m really grateful for it. Part of the reason is that I consider it my job to try to be articulate about what my project is. It makes writers’ jobs easier.

PT: You use the word “project.” A project is like an assignment with a definite goal, an end. Is that the case with your work?

SL: When I said the word I wondered if that’s really what I meant. On some level I think about it like that. It’s a game for me, on one hand. Obviously I have my own obsessions, like anybody else, and they pop up all the time.

PT: You just divided your practice into two: game and obsessions.

SL: There’s a compulsion to repeat. In other words, the game is never won.

PT: Has there been a psychoanalytical analysis of your work?

SL: Some of the feminist critiques that are coming out of Lacanian theory. I can’t think of anything extensive.

PT: It sounds like a reading that you’ve made yourself.

SL:Yeah, most recently. In my earlier career there was a lot of Frankfurt School theory being applied. Then as I’ve rekindled my interest in psychoanalytic theory, the critics picked up on that.

PT: There was the point made about your earlier work which was that you appropriated images from art by men. You were cast as a women re-making men’s imagery.

SL: In the late ’70s and ’80s, the art world only wanted images of male desire. So I had the sort of bad girl attitude: you want it, I’ll give it to you. But of course, because I’m a woman, those images became a woman’s work.

PT: What does the expression, “images of male desire mean”?

SL: It means that you consider the great modernist paintings as images or representations of their desire… At first I found Lacan extremely difficult, but when I really started to get interested in it I read a book called Feminine Sexuality with two very good introductory essays by Juliet Mitchell and Jacqueline Rose. That was a real turning point for me.

PT: Why did you become interested in Lacan at roughly the same time as everybody else here? Why did Americans and others suddenly become enamoured with this work?

SL: Speaking for myself, I found Frankfurt School theory insufficient, and I had an intuition that an answer might be in a more psychoanalytic reading of things. As an artist, I make the pictures that I want to make and I look for theory that I think is going to help me in a different kind of language. It’s not that the theory precedes the work.

PT: Certainly, some theoreticians are incredibly influential — in my case it was Barthes — but I wonder whether in time these names will be flushed out of the art system like Merleau-Ponty and Wittgenstein did.

SL: I also watch television, eat in restaurants and buy clothes. I do a lot of things, including reading theory. It’s not like I’m setting up hierarchy where the theory comes first and everything else comes second. It’s an activity that I enjoy, basically. It’s another kind of play. I had this idea today — it’s a rather unformed idea so I’m reluctant to put it into print, but I’ll see what you say about it. I was thinking that what is wrong with a lot of Frankfurt School theory is that it assumes that art is about power and that, for me, art is about play.

PT: Is play about power too? It does involve oppositions and competition, and often a victor and vanquished.

SL: I guess that play can be a theatrical representation of power.

PT: Why do the art world and a lot of artists privilege the intellectual pursuit over those entertainments that you mentioned?

SL: I think it’s because we’re worried that they won’t take us seriously.

PT: So what do you think of journalists who write about an artist’s taste in shopping, or movies or records. Is that valid criticism?

SL: Sure. But I don’t think it’s true that all critics want to discuss artists in intellectual terms to begin with. All artists don’t read. There have always been critics who are intellectuals and artists who are intellectuals, but they are not necessarily the whole situation. And I don’t want to imply that they’re in any way better than artists who aren’t intellectuals.

PT: You mentioned your obsessions. What are they? What do you call them?

SL: It’s funny. I was just reading an interview with Ross Bleckner who said that the reason he makes art is because he can say things that he would never allow himself to say in any other language. I feel pretty close to that.

PT: Do you have names for these things?

SL: Yes, but not for public consumption [laughs].

PT: Do artists often withhold the truth about the productive mechanism of their work —their career moves, what we politely call their “strategies”?

SL: Right. But the unconscious is often what makes art compelling. If we weren’t artists we might be hysterics.

PT: In art now, in New York, the unconscious is all you’re allowed to talk about. The conscious aspect of the art production, the realities of its marketing, is what remains unspoken. It reminds me of Warhol’s quip on Popism — that Pop art put the outside on the inside and the inside on the outside, which is like the situation in this neo-Pop era: the consciousness of art is the career moves of an artist, but this is hardly ever admitted.

SL: One of the reasons that I talk about it with you is that you don’t get offended by it. We’re not really supposed to talk about it.

PT: When your stripe paintings first surfaced, you told me that you considered them to be generic stripe paintings. Later I spoke to the editor of an American art magazine and she used the same word. In a sense, there’s almost a generic response to your generic stripe paintings. In fact they’re generic history paintings referring to the history of the stripe — referring to Brice Marden, Blinky Palermo, Bridget Riley, even Kenneth Noland. Is the act of reference the content of the paintings?

SL: That’s just the modus operandi. The content is the discomfort that you feel at the déjà vu that you experience. The discomfort that you feel in the face of something that’s not quite original is for me the subject matter.

PT: Does that mean that you do not have to continue to appropriate photographs and paintings to elicit that response?

SL: What I discovered is that it’s even more troublesome when something’s almost original.

PT: If you’re trying to create a feeling of déjà vu, then you are addressing a quite specific viewer — one who knows art history and one who knows your work.

SL: Right, I guess that’s my ideal viewer. Others experience them, I think, as formal paintings. I think all artists have a very small, idealized audience, and whoever else likes the work, well, that’s great.

PT: That audience is like your super ego. Do you address a general viewer in your works?

SL: I never think about it that way, so probably not.

PT: It seemed so at Documenta 7. The Egon Schiele appropriations were self-portraits of a male artist that referred curiously to the overall situation. How much irony was involved?

SL: Like an artist, I’m trying to describe my experience and because I’m a woman my experience is different from a man’s. I really thought it was a joke. Schiele always seemed to be the ultimate male expressionist, the ultimate bohemian, so I thought it would be amusing to try on his clothes, as it were.

PT: His birthday suit! You are suggesting that your earlier direct appropriations and your stripe paintings do the same thing, but the history of art has a different role in both of those oeuvres, however.

SL: Yes, and I seemed to have straddled two very popular movements. That’s my public persona. In terms of my private obsessions, nothing has changed very much.

PT: Would you appropriate the work of a woman artist?

SL: I never have, but …

PT: Would you appropriate the work of a contemporary?

SL: Never consciously, though I’ve been accused of it. I am very influenced by the work around me, sometimes I’m even more interested in the people who are not thinking about the things that I am thinking about. I think the original subject matter of my appropriated work was the anxiety of influence.

PT: I guess that you are referring to appropriation and the thing that’s happening now.

SL: You mean the New abstraction?

PT: Did you know that it was coming around the corner when you started painting the stripes?

SL: Well, I did know that I personally was very bored with figurative imagery. I suspected that a lot of other people were too, so when I did the drawings after Malevich, I just found it so refreshing after this bombardment of figurative imagery that we were all involved in, that it just seemed to me like a nice cool drink of water. So it made a lot of sense that other people thought that way too.

PT: You must have a fickle taste in imagery if you can get “bored” with figuration after a few years and want to go abstract.

SL: I think that people do something for a while, and then they get bored and do something else. Their major concerns probably don’t change very much. Certainly the symptomatic aspects change. It keeps life interesting. “Fickleness” has a pejorative edge to it that I don’t think is appropriate. One has to keep oneself interested.

PT: So the figurative or abstract face of your work is just the exterior.

SL: Yes. They’re not really crucial.

PT: But the interior is invisible.

SL: In a way, yes — the things that I really care about. The struggle for any artist is how to represent what the real conflicts are.

PT: What are they?

SL: In the most abstract sense, I think that I’ve always been involved in issues of representation, what it means to represent something.

PT: It was said that your appropriated photographs played a part in the ‘end of painting,’ but, when I first met you, you told me that you were going to make paintings to show that painting is not the enemy. It seems that if someone says that your work is about this or that, you prove them wrong.

SL: I take criticism very seriously, so when somebody says something that really strikes a wrong chord, then I realize that there must be some truth to it [laughs]. I think about it very hard and ask myself — why have I denied that aspect of my work, denied painting in this case. I have a painting up in the back room at Mary’s now and it’s next to an early Brice Marden. I looked at the painting and said to Mary that it’s really funny because I stopped painting because I believed that Brice Marden had made the last painting that anyone could make. It’s taken me fifteen years to see that endgame art is a field that I can move around in.

PT: The resistance to the idea of art as game theory is based in transcendental notions of the art. To many, it is a repugnant idea that an artist does something purely in response to the art world.

SL: But when I call it a game, I don’t mean that it doesn’t have any heart-felt components.

PT: The stripe paintings are the apotheosis of non-reference, as most abstract painting was in its idealist manifestations.

SL: That’s what I think is so amusing about the stripe paintings, that ostensibly they are non-referential, but on the other hand they have all these references.

PT: It’s ironic that while being so ‘empty,’ they’re so ‘loaded.’

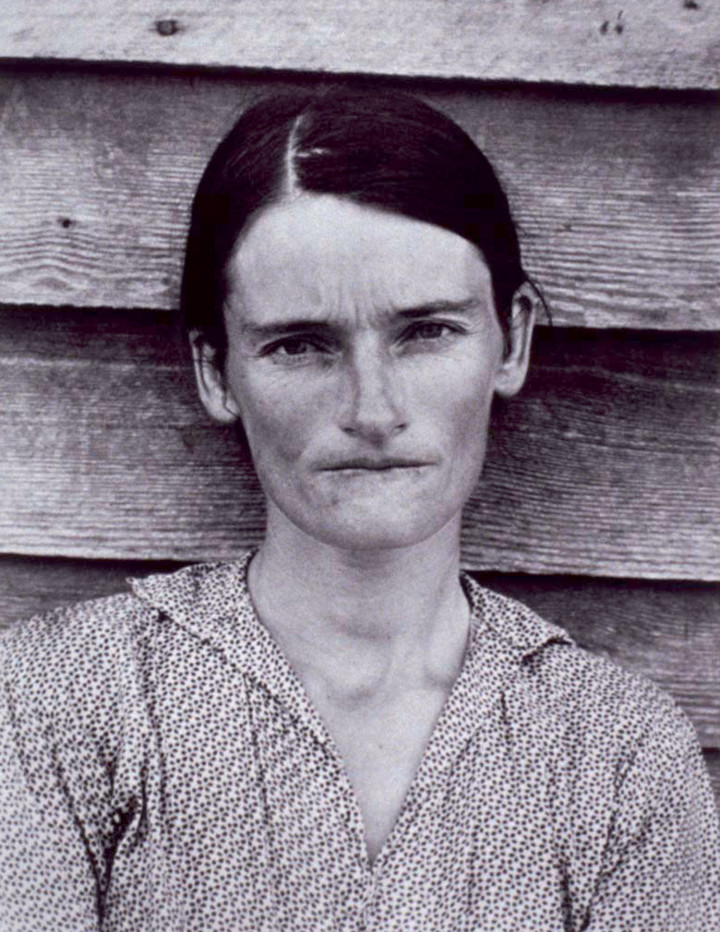

SL: Which is the opposite of the direct appropriations which appear to be so loaded in content but as photographs of photographs they have no referent, in a way. A Walker Evans is the same as an Edward Weston on a certain level, which annoyed a lot of people when I first did them.

PT: How long did it take for sales of your work to catch up with your critical reputation?

SL: People have been writing about my work since 1977. I’ve only started living off it in the last few years.

PT: Since 1984. What were you doing before that?

SL: A lot of waitressing and commercial art…Teaching.

PT: And laying-out The New York Review of Books too. Did you deliberately change your style for the sake of sales?

SL: It’s not that I changed my style, but I changed medium. I was playing one game and decided to play another game as well.

PT: To play the game of the market entailed greater visibility. What are the stages that an artist passes through in playing this game?

SL: No matter what you do as an artist, there are certain parameters, certain choices. The choices and things that curtail your activity are things like how much time you have, how much space, how much money…

PT: You knew that the stripe paintings would make you more money than your photographs.

SL: You’re asking why painting is privileged in this way? It’s an interesting question. I’m not sure about it. The more I make art, I see the reasons why people use these materials. It’s because they’ve been proven to last. When people try to use new materials, one is never quite too sure.

PT: It sounds very traditionalist.

SL: It’s ‘conservative’ in the literal sense of the word. But I haven’t abandoned the photographs. What I realized was that I could make them too. My decision to paint was a decision on the level of desire as well as a decision to work in a less marginalized area of the art world. I started out as a painter. I wanted to see what it felt like to allow myself to paint again. I find that I like painting more than I enjoy arguing with photolabs.

PT: I like the fact that some of your checkerboard paintings are called “Checks”… I guess that going to Mary Boone Gallery was a major step in the market game too.

SL: That’s one of those questions like, “when did you stop beating your wife?” [laughs]. I went there for all the obvious reasons. She’s a very good dealer. Mary talks a lot about artists being the Id of the art world. It’s certainly what my Schieles were about.

PT: What does it mean?

SL: It’s the part that acts without inhibition, that follows its own desire. That’s what I take it to mean.

PT: Is it destructive?

SL: Obviously we’re talking about a theater in which artists represent the Id. Artists are subject to all the things that everyone else is, but we’re given a kind of… rope which allows us to represent parts of ourselves that other people don’t allow themselves publicly.

PT: That’s the cultural agreement that privileges artists, sure. But what happens if that cultural agreement falls apart, if there’s a cultural disagreement? Isn’t this what is meant by the notion of an epistemic change?

SL: Yes, then something else will happen. In general, artists are now much better behaved than the generation before us, because we’re required to be.

PT: Do you want to see the roles change?

SL: Well, one nice thing about having success is that it brings with it a little bit of power.

PT: “Success is the best revenge”.

SL: That’s obviously true.

PT: But do we lose the will to transform things as we get more successful?

SL: I don’t know, I’m not that successful. It’s true: somebody asked Ralph Nader once why he didn’t run for president and he replied that if he was president he wouldn’t be able to do anything. The thing about the art world is that it’s not about real power. I think it’s highly developed play — for us and also for people who do have real power.