Shu Lea Cheang has lived a number of different lives: as a queer media activist, a cyberpunk filmmaker, and an early contributor to the canon of internet art. Her work Brandon (1998–99), the first work of web-based art commissioned and collected by the Guggenheim Museum, New York, conceptualized an online digital panopticon at the same time as addressing the rape and murder of Brandon Teena, a trans man, in Nebraska in 1993.

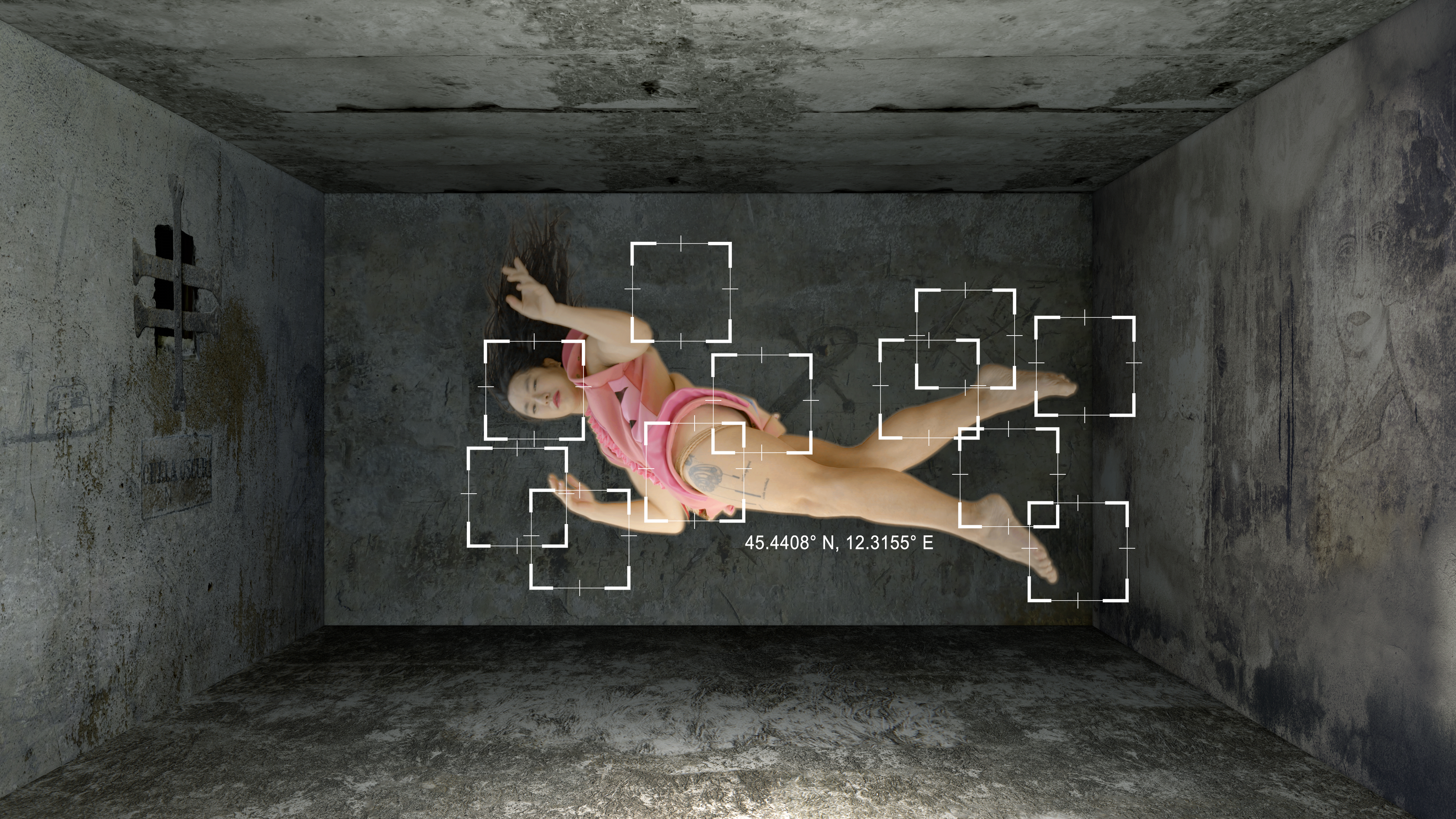

This summer, Cheang will represent Taiwan at the 58th Venice Biennale with 3x3x6, a site-specific project housed in Venice’s Palazzo delle Prigioni, a sixteenth-century prison (where, famously, Casanova was once held). The multimedia installation’s title refers to an industrial standard for prison architecture globally — a nine-square-meter cell equipped with six surveillance cameras. Taking the panopticon interface of Brandon as its starting point, the project considers the history of freedom and confinement in relation to contemporary surveillance technologies, as well as incarceration on the basis of gender and sexuality. Flash Art spoke to Cheang, as well as the pavilion’s curator, Paul B. Preciado, on the occasion.

Tess Edmonson: Your project will include ten films that each correspond to real cases of the incarceration of a subject on the basis of gender and sexuality, including Casanova’s imprisonment in the Palazzo delle Prigioni and Michel Foucault’s imprisonment in Poland, as well as contemporary cases such as that of someone incarcerated in Taiwan for HIV nondisclosure. Could you speak a bit more about these cases?

Shu Lea Cheang: The film treatment of the ten cases will actually be quite minimal, abstract, and totally fantastic. For example with Casanova, we are actually focusing on the condom.

Paul B. Preciado: In the late eighteenth century Casanova was one of the first people to publicly promote the condom. And this was, for us, more interesting as a way of relating this historical case of what you can imagine as straight masculinity to the ’80s and ’90s or even the contemporary politics of AIDS prevention, for example. We’re morphing some of these cases up to the point that we change gender, sexuality, age, body type, everything. Casanova is actually going to be played by a Taiwanese dancer.

SLC: We have one case from South Africa, Zimbabwe, one case in Taiwan, one case in China, one case in Iran, a case in Germany, in France. The filming will allow some of the characters to cross time, to have encounters — like Michel Foucault meeting a French Muslim philosopher in a contemporary sexual assault case, for example.

PBP: We decided not just to look at particular cases, but mostly at typologies of cases. So for instance one of the typologies of cases is how HIV-positive status became the object of surveillance, in particular of legal and state surveillance, and this is the case very much in Taiwan, according to which, if you are HIV positive, immediately you are put into a state program in which you have to disclose your status to any institution in which you are working and to any of your possible partners. Which means a full disclosure of your biological status at every point: at the professional level, institutional level, your school, university, any kind of professional work that you do, and, of course, your “private” life. This is another question for the project: What is private life in a society that is fully surveilled?

TE: Is this project in conversation with prison abolition, or with visions of justice that depart from a carceral model? Can we imagine a relationship between the abolition of prisons and the abolition of gender?

PBP: When we speak about abolition of gender, I remember the feminist debates, even the radical lesbian debates I was in when I was twenty. People spoke about abolition of gender as though gender was an abstract category that didn’t really exist, that you abolish it and that’s it. But in the work that I’ve been doing for the last fifteen years and even more now working with Shu Lea, what is more interesting for me is to identify the specific technologies of gender production and gender inscription. We say “abolish,” but maybe it’s not the right word, because those technologies cannot be fully abolished. They can only be intervened upon; they can only be hacked. For instance, yesterday I was speaking about at least abolishing the protocol of assigning gender at birth. That can be abolished, certainly. But this is already a technology. It’s a visual technology, it’s a medical protocol, it’s a clinical test.

If you think about the historical development from anthropometrics into biometrics and now into digital technologies, you see how these anthropometric technologies were invented for colonialism. And then how they are used for mapping gender and sexuality. For instance, there is an algorithm that claims basically through facial recognition to say if you’re straight or if you’re gay. They claim to identify your racial background, just with a single headshot. You think about the selfie, which we’re constantly doing, so they don’t even need to take us into the hospital to measure our heads; it’s already online. But my problem with this kind of reflection is that then the landscape of political action becomes fully dystopic, as if there’s nothing else we can do. Which is not true.

So gender cannot be abolished just by the decision to abolish gender. No, the issue is what are the technologies of gender production that we can intervene in, modify, hack, and act upon. So we will have to pinpoint all of them — it can be gender inscription, it can be hormones, it can be technologies of reproduction — and go into the details.

Both of us are for the abolition of the prison system. At the same time we remember the debates that were taking place in the ’70s and ’80s, saying not just that we should abolish the prison regime but also that the prison regime will drop down by itself because of the advent of new technologies. You can think of the Deleuze and Guattari argument, or of The Societies of Control, which says that we’re complicating new forms of control that would not require architecture, and then the whole prison system will be transformed and eventually collapse. But what we see in the last twenty years is the opposite. It’s this kind of juxtaposition between a global, digital regime of surveillance juxtaposed with an almost archaic prison regime. These two regimes coexist, and they seem not to have an intersection either — for instance prisoners cannot use the internet. Because the prison is an archaic system, really, inscribed within this big-data, global surveillance device, but at the same time it’s outside of it.

SLC: It also depends on how you define prison at the moment. That’s why I refer to nine square meters with six surveillance cameras: that is a totally virtual space, in addition to a space of physical confinement. But it all goes back to the whole history of public punishment, from confinement to solitary confinement and then in a bigger sense to the twenty million surveillance cameras in China, which constitute a much bigger prison in virtual space. I guess that’s why in terms of the question of abolishing gender or prison… it’s not a slogan I would use, let’s put it that way.

TE: Your project’s invocation of the social construction of subject positions in surveillance technologies reminded me of Simone Browne’s book Dark Matters, which traces the history of contemporary surveillance practices in the United States in European colonial expansion and transatlantic slavery. She writes: “Rather than seeing surveillance as something inaugurated by new technologies, such as automated facial recognition software or unmanned autonomous vehicles, to see it as ongoing is to insist that we factor in how racism and antiblackness sustain the intersecting surveillances of our present order.”[1]

Is this consistent with your thinking about surveillance as a mechanism for constructing and policing gendered and racialized identities?

SLC: Again, this is one of the things we have do deal with in thinking about the relationship between the regime, the national and political entity, and so-called sexual and racial minorities, those we would consider genderqueer or any kind of racial minority. Any particular reason they could be prosecuted might in the end have more to do with race and sexual preference rather than any crime.

TE: Browne describes a set of practices she calls “dark sousveillance”: a way of intervening in the racializing order of surveillance by obscuring the subject, surveillance from below, or other forms of scrambling or hacking existing systems.[2] It reminds me of the way that Paul described your work as the creation of “dissident interfaces”: using digital materials to intervene in the internet’s construction of gender and sexual identities.

TE: Brandon is cited as the starting point for the exhibition in Venice, and both projects look at the intersection of sexuality, digital technologies, and carceral violence. How is it to revisit this material over twenty years later?

SLC: At the time, there were two stories, two news items that inspired the project, both in 1993. One is that of Brandon Teena, who was raped and murdered in Nebraska. The other case was covered in a Village Voice story by Julian Dibbell about rape in cyberspace: a totally constructed virtual space where the so-called rape was conducted verbally. That time was really the beginning of cyberspace, and there was advertising like, “there’s no race, no gender, no age in the internet,” this kind of utopian vision of what the internet can promise. Now, we cannot say there is no gender. It’s like what Paul was saying about the abolition of gender assignment at birth; I think if we were advocating for the abolition of gender then we would be quite naive.

Another thing is that in the ’90s when I was making Brandon, a lot of these trans technologies were emerging — prostheses, like attaching a penis, attaching a pack, so you could pass. Today gender is no longer defined so much on that particular apparatus or prosthesis. I still revisit Brandon only because I feel like in Brandon I was already dealing with the panopticon interface and the incarceration of those who would still be called “sexual deviants.” So twenty years later, we’re revisiting Brandon or revisiting the panopticon interface and elevating the concept into a larger context of a global digital surveillance system. With regards to Brandon, it’s a starting point but also a departure.