Like most disasters, it’s said the day was cloudless. It’s June 11, 1955, at 6:25 p.m. at the 24 Hours of Le Mans sports car race, and in one minute, a slew of then-state-of-the-art race cars will vault over a small earthen barrier separating the track from the gathered spectators. Physics dictates the subsequent spectacle. Built of an alloy composed heavily of magnesium (highly flammable, apparently), the Mercedes-Benz entry into the race, the 300 SLR, bursts afire, egged on by diesel and other combustibles. Eighty-three die, and 120 are injured in the then-deadliest auto accident in history. For three decades following, Mercedes terminated their racing program, with the two remaining 300 SLRs preserved as relics of the triumph of technology over life, as ever.

Flash forward to May 20, 2022, at the Stuttgart Mercedes-Benz Museum: an anonymous collector purchases one of the two 1955 300 SLRs for 135 million euros — unsurprisingly, this is the largest sum ever spent on an automobile. Another record. How is such value produced? This car itself acquired its worth when unable to fulfill the use case for which it was made; its prestige is born from its position as evidence of the grand waste of manufacturing, as potential energy squandered before conversion to kinetic. Disasters create value. Value creates fantasy. At an auction, value is unknown at the outset, with anticipated potential to be realized at the hammer strike. It’s at this moment that money, at an ungodly scale, is vaporized. Blanchot’s eternal dictum: “The disaster takes care of everything.”1

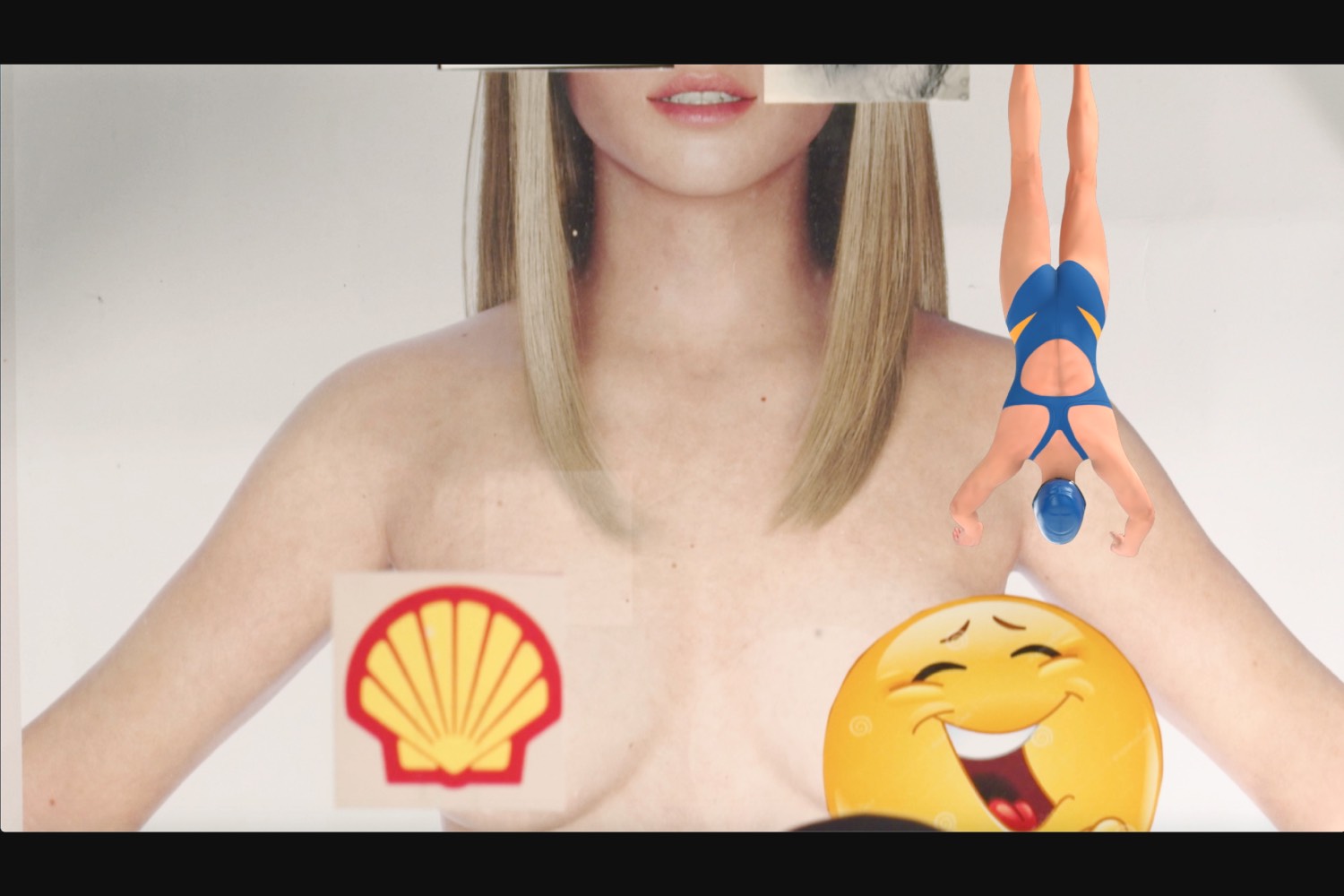

I spoke with Sara Cwynar, coincidentally, a few days before the eighty-ninth anniversary of the so-called Le Mans Disaster. “It’s always important for me to find things in the real world and then be led by them. I need to follow my obsessions,” she says, referring to the 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, which has guided recent inquiries. Previously, such objects of fascination have included the rose gold iPhone (2017’s film Rose Gold), bric-a-brac sourced from eBay trawls (among others, 2016’s Soft Film), makeup with the brand name Cezanne, cosmetic production facilities, computerized figures endlessly swimming, printouts of celebrities du jour, her friends, statues, catalogue snippets, and endless concatenations of photos in a camera roll. Cwynar’s preoccupations and vocabulary of the image maneuver between discipline, place, and degree of physicality, unsettling any concept of “real” — 3D renderings mingle amid in-the-flesh actors, images of digital avatars are printed out onto paper and cut out with scissors (not lassoed in Photoshop). Bathed in studio lighting, they all appear to have similar levels of construction. At such junctures, increasingly untenable divisions erode — between analog and digital, replica and original, and other oft-repeated dichotomies.

Such maneuvers are on full display in Cwynar’s exhibition “Baby Blue Benzo,” opening at 52 Walker, New York, in October. A two-channel film and installation, Baby Blue Benzo (2024) locates the 300 SLR as a fulcrum to explore how objects accumulate fiscal and social value. Across her work, Cwynar probes valuation systems, questioning the role that images play in producing and representing our desires. “In a way, ‘Baby Blue Benzo’ is an archive of fantasies: of all the fantasies which go into making a car so valuable.” Fantasies present osmotically, irrespective of gaze. Cwynar’s work seeks to deracinate these media fabrications (social and otherwise), remove them from their contexts, and denature them.

The film’s major players include a life-size model of the SLR (a print mounted on plywood), the remaining SLR (the one not sold in the auction!), models in bikinis à la car commercials, marble statues, models in Victorian gowns, a cutout of Pamela Anderson, and Pamela Anderson herself. Throughout the film, the cameras are conspicuously present — one 16mm and one digital — on a circular track surrounding the car, filming both the subjects of the film and themselves. The 300 SLR, mounted on plywood, attains a lenticular quality when orbited by the cameras. When viewed from the front, under the lights and subject to the transfiguration of filmic lighting, it appears to be a fully three-dimensional object in physical form — the car itself, there for you, waiting to be viewed, shockingly real. Just as quickly as it is endowed with a sense of thingness, the totality of the image is revealed as the camera swivels; artifice is made apparent even a couple of degrees away from dead straight. The illusion falters. Advertising is an act of persuasion, and it’s only convincing because you know, in the back of your mind, that you’re being tricked.

Before an MFA at Yale in 2016 jumpstarted her art career, Cwynar worked in graphic design, a background evident by her recognition of the pathos of reactionary appeals toward a yearning for the past — nostalgia. “When I was first coming up in design, things were very nostalgic. Is it a reflection of current times that we always want to go back to earlier modes of making images?” Cwynar’s images, be they still photographs or those set in motion in a film, assuage a present; they confound the aesthetics of a singular time. They are analog, richly grained and sensuous, yet digitally sharp, manipulated; organic, yet posed; contemporary, yet reminiscent of a Sears catalogue, a production still in Technicolor selling you a product that no longer exists — a typology which recalls, vaguely, a past, but without specifically referential temporal markers, toward more of an affective image-language of something bygone. Graphic design, as advertising, seeks to present past fantasies as desires of the future and, as such, naturally reifies a backward gaze.

Cwynar’s images are rarely at rest. “The scroll is essential,” she says of the ever-present movement in her films. Akin to the visual experience of navigating a contemporary cityscape or an app, rarely is Cwynar’s viewer treated to the reprieve of a stilled image. As our contemporary visual field has become overgrown, so too are Cwynar’s aesthetics bustling: “I’ll spend a full week on ten seconds.”

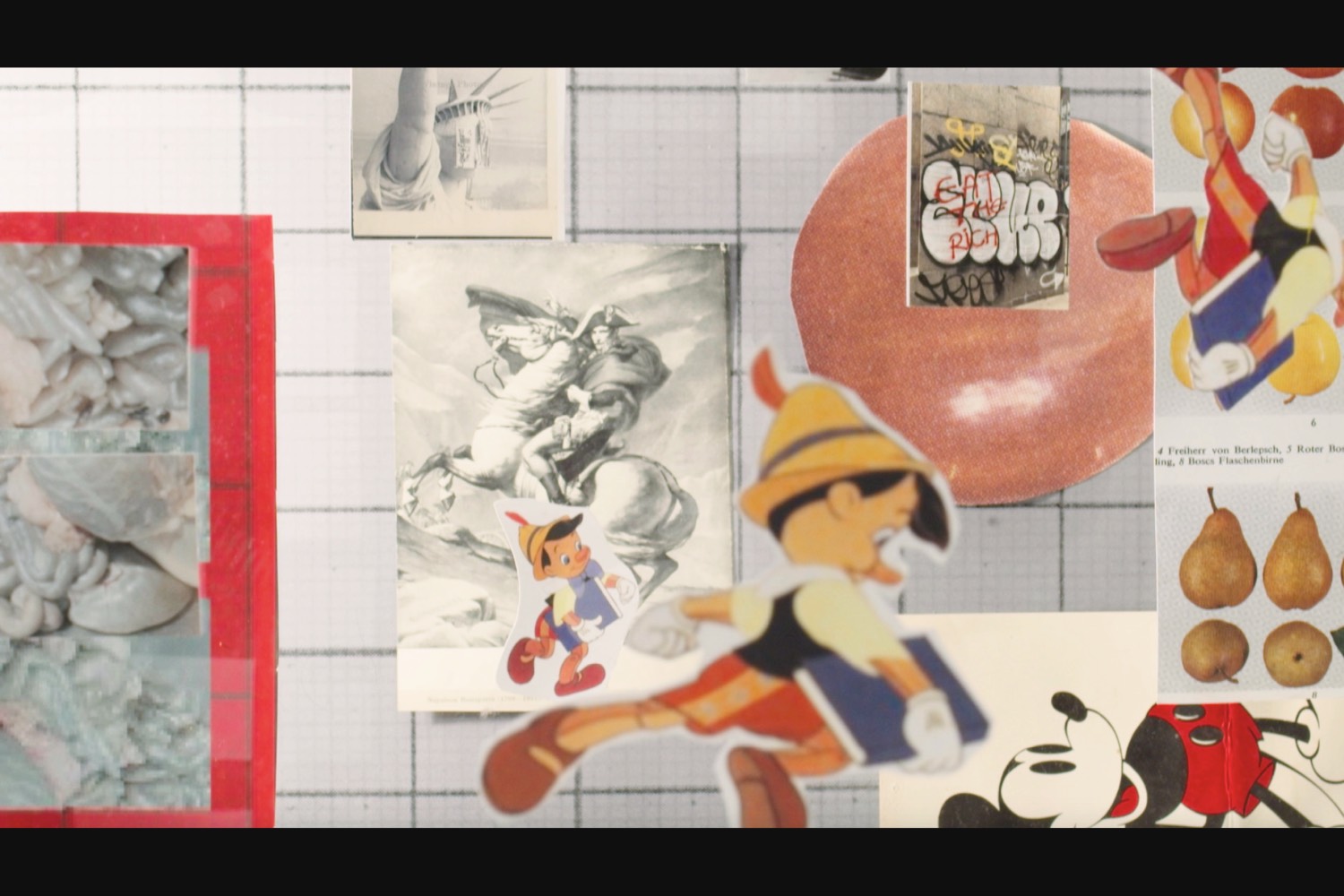

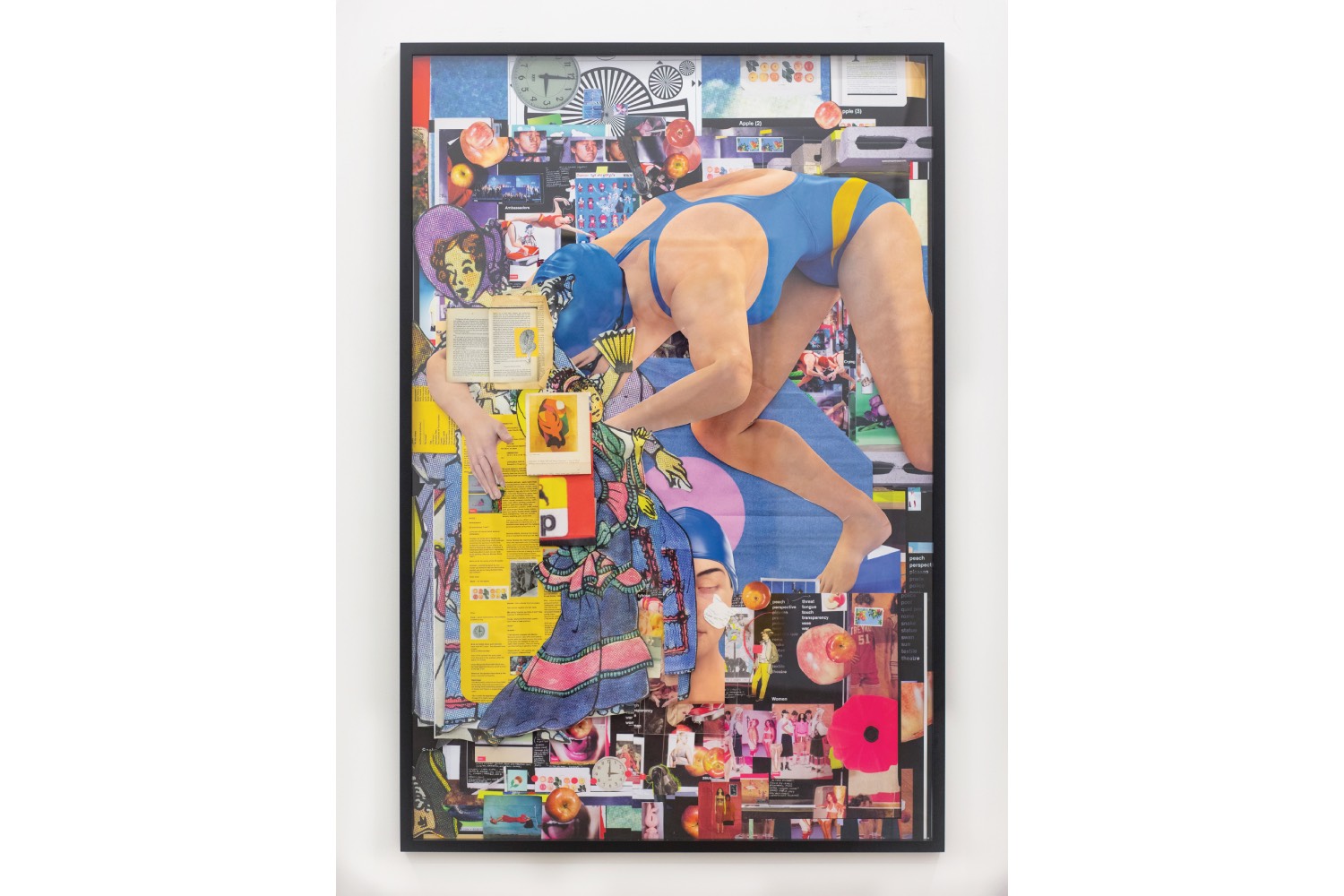

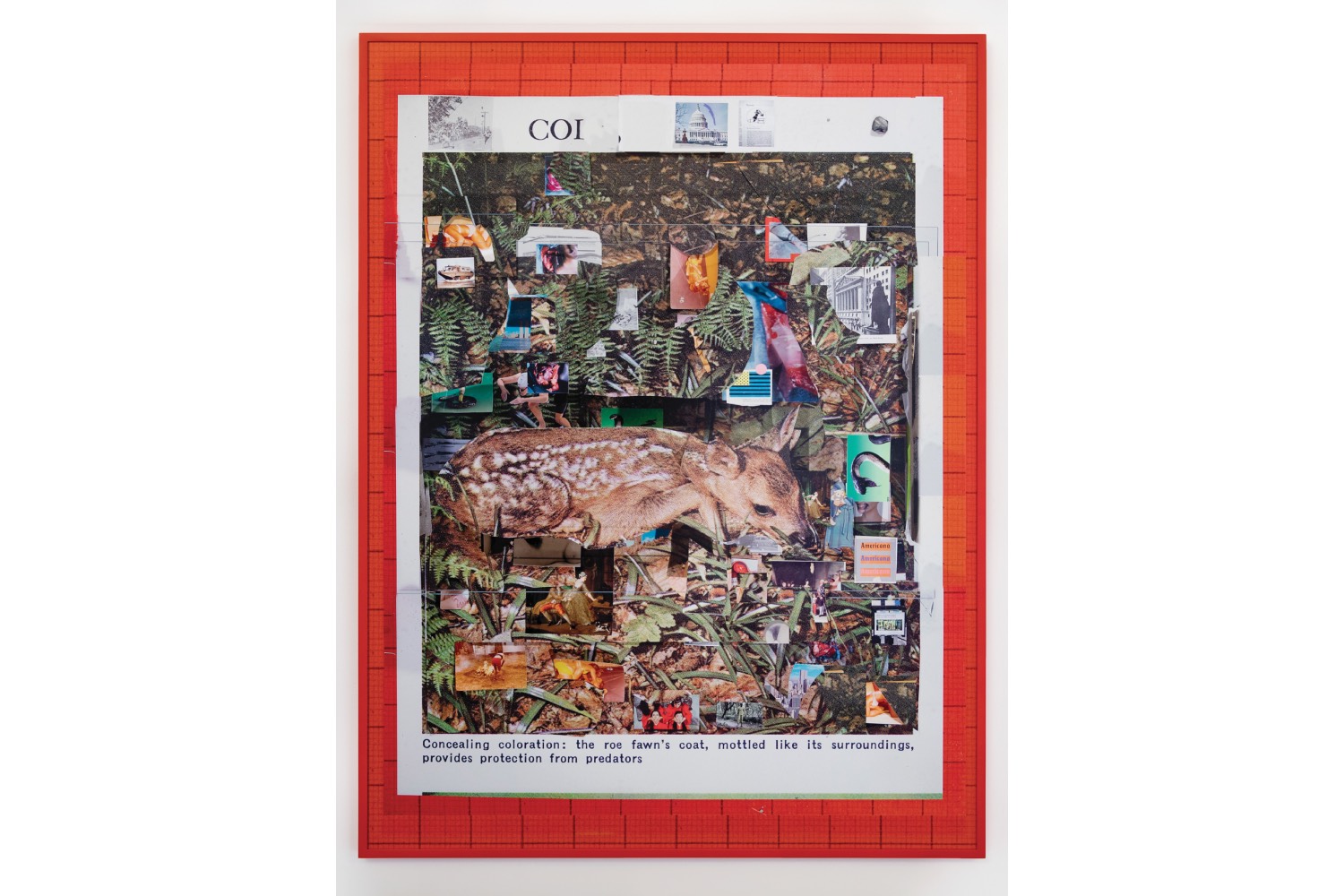

Take 2021’s sprawling six-channel video installation Glass Life. The title of the work is taken from Shoshana Zuboff’s book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (2018); Zuboff uses the eponymous term, in Cwynar’s words, “to describe the pervasiveness of data-driven technology, which operates under the cover of effortless connection and convenience, while quietly eroding privacy, social bonds, self-determination, and individual will.”2 The film is an anxious combination of digital and analog in which images, some digital renderings, and some literal cutouts flow ceaselessly from the bottom to the top of the screen, superimposed over a grid. Multiple planes move at once — sometimes the camera, sometimes the images, and sometimes the background; Cwynar employs multiple layered glass panes in a practice similar to mid-century animators. Such images include Pinocchio, self-portraits, wristwatch advertisements, intestines, an emoji of a pig, Margaret Thatcher, paperclips, perfume bottles, and the World Trade Center. Occasionally, the scroll is replaced by a shift to full-screen video: the interior of a museum, an airport tarmac. Any individual locale is frangible; the associative logic of the film has a quick metabolism, privileging jumps.

Paralleling the constant scroll, a constant narration presides, voiced by Cwynar and Paul Cooper, who is a consistent presence in Cwynar’s films (Cwynar: “He’s got that laconic, authoritative man voice”). The recited text is a mix of Cwynar’s writing and sourced texts, organized, in broad strokes, around the processes of self-formation and capital’s impinging upon such formation via media apparatuses. From Glass Life: “We have to watch ourselves become ourselves in order to be ourselves, over and over again.” The voiceover track in Baby Blue Benzo, also voiced by Cooper, draws from a similar breadth, plucking from sales literature for the Benz, Allan Sekula, Charles Baudelaire, Saidiya Hartman, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and original text written by Cwynar.

Glass Life also forms the basis of Cwynar’s 2025 show at the ICA Boston. The exhibition has several reference points, chiefly among them German art and cultural historian Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29) — a sprawling sequence of sixty-one panels in which Warburg brought together hundreds of images to express imagistic continuities across era and origin, in opposition to an understanding of the art-historical canon as a linear timeline of continual Western progress. The ICA show begins at the end of Glass Life with an alphabetical list of terms related to the film’s research and production. The list begins: “Ambassadors, animals, Apple, Balenciaga, Bayer, beauty, Bellmer, Berenice” and so on, through the abécédaire of Cwynar’s actual research interests, as well as terms that began to show up in social media ads as a result of Cwynar’s online habits during the film’s production. It’s as much an index of thought as it is a reflection of how thought is bent by algorithmic insistence. The installation, sprawling across the entire gallery space, will amass image, video, and text material relating to each term, a mass aggregation of signal and noise, of the relevant and the insignificant, all the products and byproducts of thought. In producing oversaturation, Cwynar seeks to investigate what occurs when information is gathered; what hidden meanings emerge from this proliferation? Writing on the Mnemosyne Atlas, French philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman approaches Warburg’s larger project as one invested in “a knowledge-movement of images, a knowledge in extensions, in associative relationships, in ever-renewed montages, and no longer knowledge in straight lines, in a confined corpus, in stabilized typologies.”3 So too does Cwynar approach the image as eternally subject to motion and, when in motion, capable of fracturing “stabilized typologies” which tie objects to a “confined corpus” and preserve repressive norms.

In the Arcades Project (1982), Walter Benjamin writes that “history decays into images, not into stories.” On the evening of November 30, 1936, the Crystal Palace, a sprawling glass and wrought iron structure erected in London to house the first World’s Fair, was destroyed in a blaze. The Crystal Palace inspired numerous copies, including the New York Crystal Palace, the Glaspalast in Munich, the Crystal Palace in Montreal, the Garden Palace in Sydney, and the Paleis voor Volksvlijt in Amsterdam. All, too, were destroyed in fires. To copy an object is to reproduce its fate, to assure the replication of a future: not to revivify its present state, but to assure a congruent end. As W. G. Sebald writes in The Rings of Saturn (1995): “On every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation.” Even before it was built or conceived of, the 1955 300 SLR was doomed. Likewise Cwynar’s 300 SLR, as a print mounted on wood, shares its fate, rebuilt and destroyed, as each rotation of the camera reveals its falsity, built-in service (and assurance) of an end. What is expressed through such reproduction? What is reproduced? Where do the images go when they themselves decay?