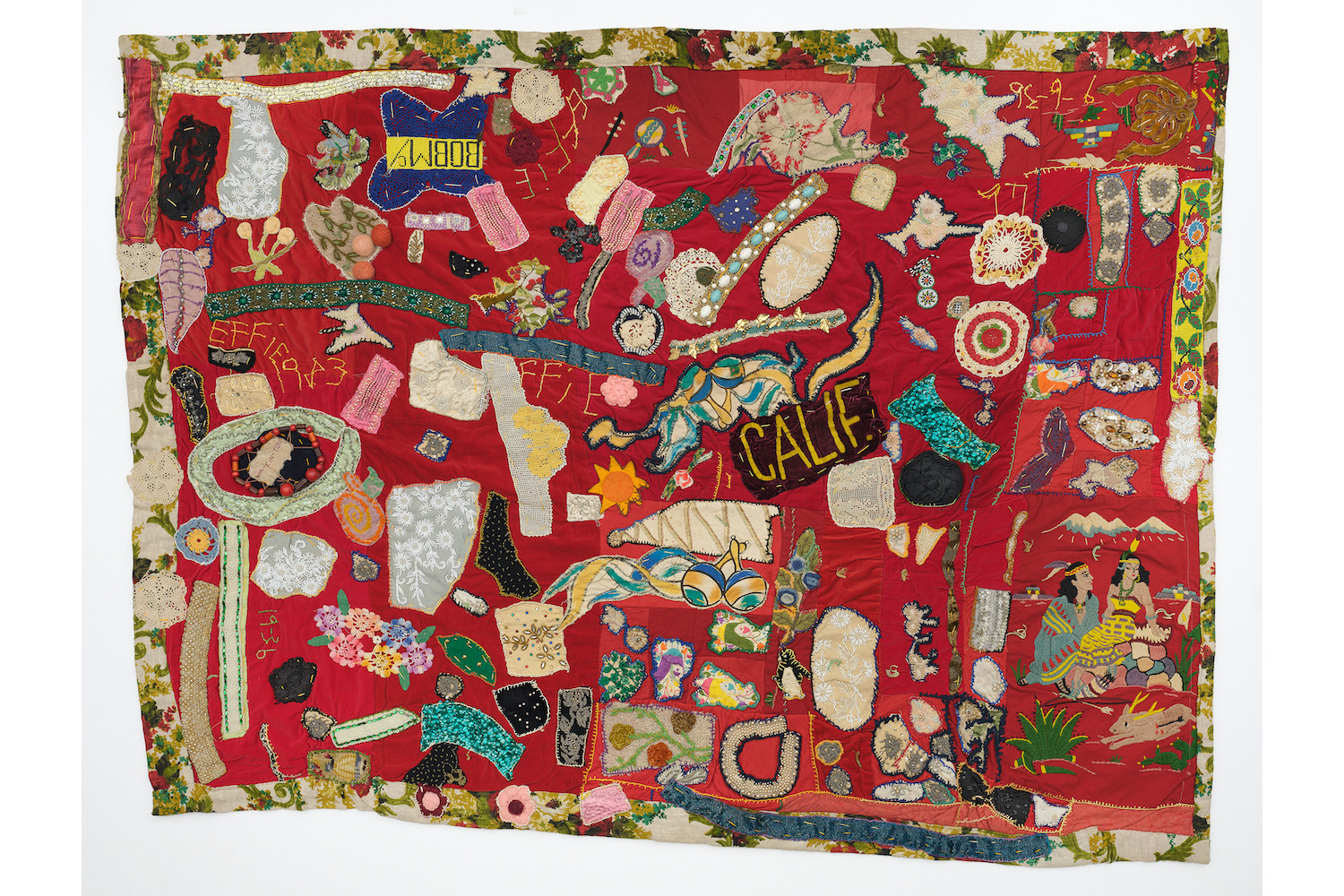

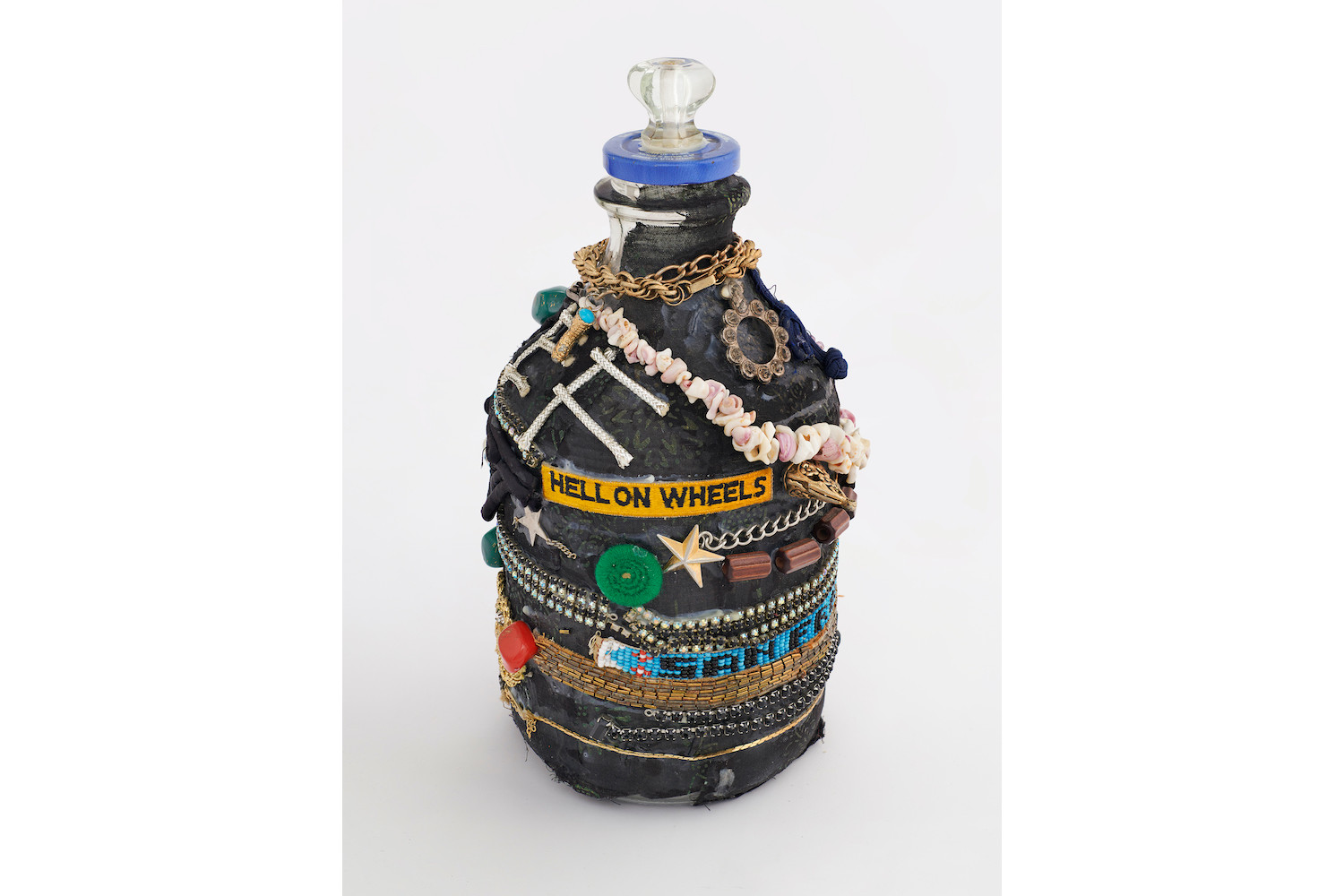

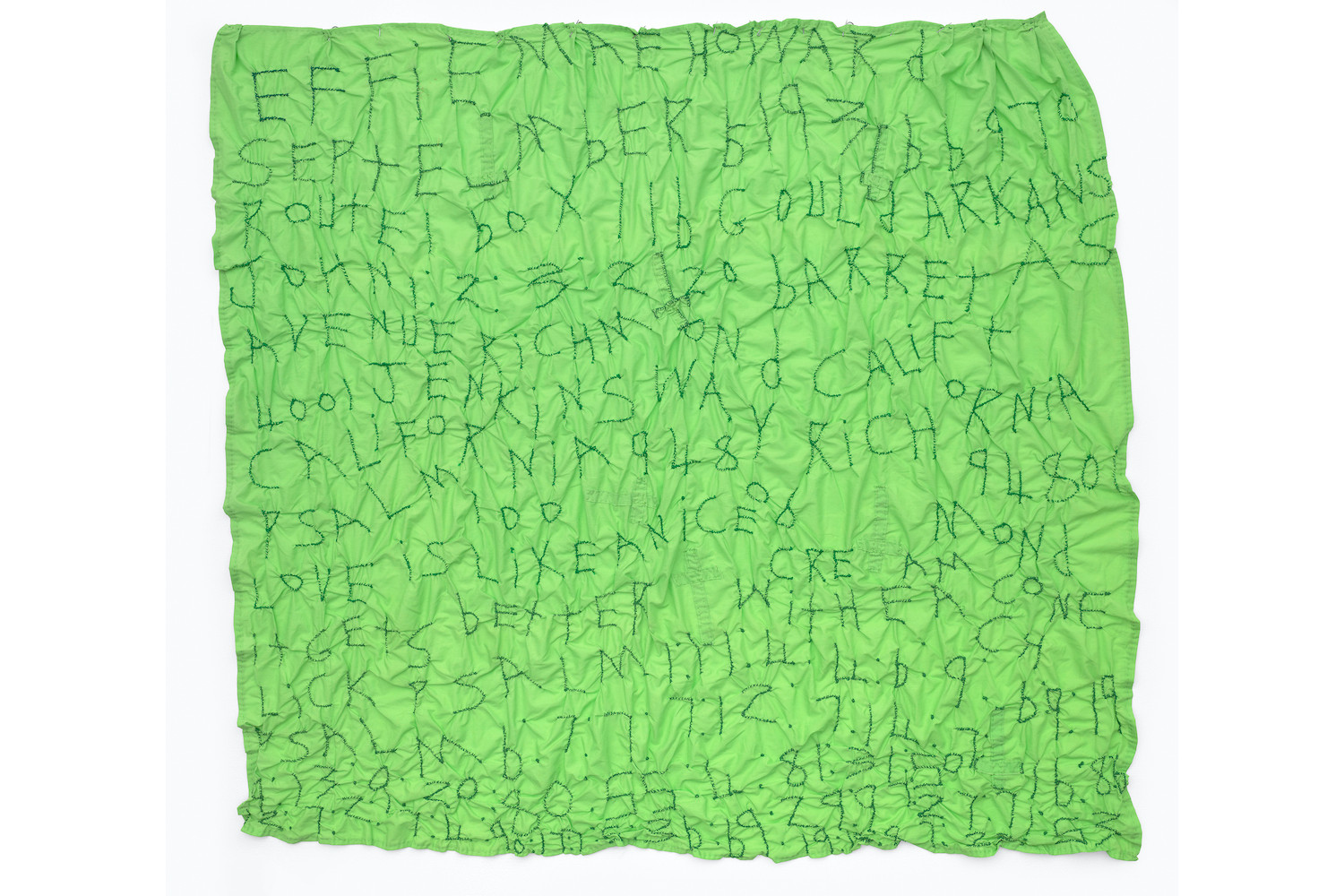

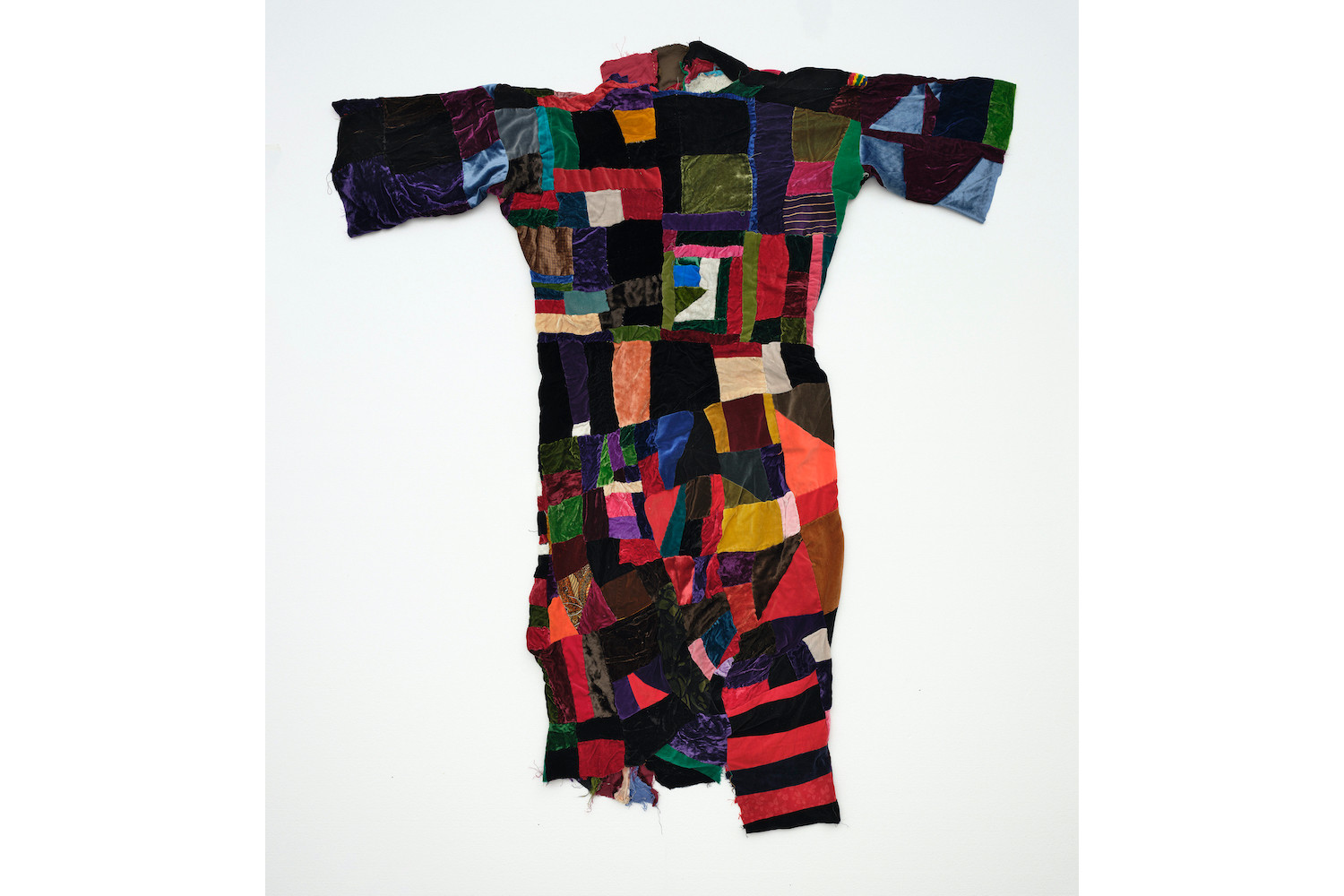

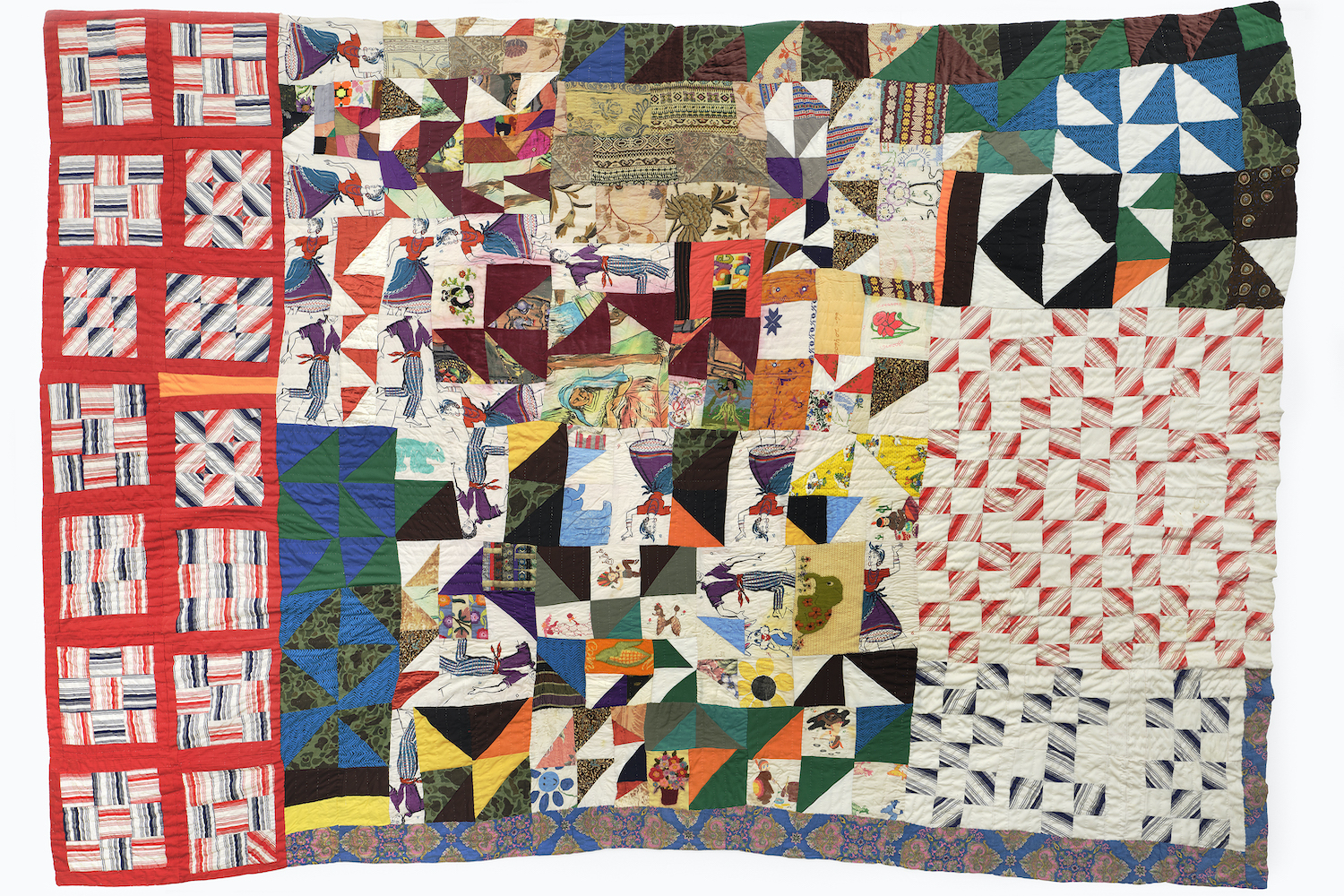

Rosie Lee Tompkins — the pseudonym of Effie Mae Howard — was a textile artist born in rural Arkansas and based in Richmond, California. There she created hundreds of quilts and textile objects that, since the late 1990s, have been widely celebrated for their compositional and material sensibility and sociopolitical subtext. Tompkins’s work defies categorization as art or craft. Yet, according to Lawrence Rinder and Elaine Y. Yau, the curators of her retrospective at BAMPFA, it engages both fields dialectically, thus transcending the still exclusionary label of “applied modernism” and ushering a genuinely global narrative of twentieth-century modern art: “It is from the perspective of craft that Tompkins’s art might work toward the promise of a more inclusive art history,” writes Yau in her catalogue essay.

Despite the premise of interpreting Tompkins’s art qua craft, the exhibition unfolds via a number of quilts pristinely displayed on the museum’s walls as if they were framed pictures. The museological strategy of displaying utilitarian objects calls for no deviation from that of the Duchampian ready-made and, conventionally, pieces of fabric are hung like modernist paintings. At BAMPFA, the adoption of this mode of display can’t help but result in a missed opportunity to develop a language of exhibition design that could speak to the material lives of Tompkins’s textile art while still highlighting its formalist qualities. It is not only a matter of offering the quilts’ surfaces, often made of shimmering velvets and glittery synthetic fabrics, to a mode of perception that is not solely frontal. Tompkins never developed instructions for the exhibition of her objects, thus leaving curators to deliberate on the orientation of the quilts; vertical display, then, forces their compositions, embroidered texts, and embedded imagery into a single reading direction.

Consider the quilts’ versos. After Tompkins’s meeting with Eli Leon, the collector and African American quilt scholar who would become her patron, she began assembling only the tops of the quilts, which would be finished, in fact “quilted,” by other sewers on Leon’s request. No verso is visible in the BAMPFA retrospective. A layered history of labor is made opaque (the quilters’ names are mentioned in the wall labels), while Tompkins’s art is celebrated in a singularized form of craft — her textiles having been periodically reformatted in a quilt-as-commodity mode at the expense of their untrimmed hems, informal outlines, and rhizomatic appendages.

It is no secret that this exhibition follows BAMPFA’s reception of a large bequest of quilts from Leon’s collection, which included most of the objects on view here. One may wonder, then, if a mode of display that had allowed for a thorough encounter with the quilts wouldn’t have shed more light on the material conditions that underlay the creation of Tompkins’s objects — conditions in which Leon played a leading role, beginning with the very invention of Howard’s pseudonym. Threaded into Effie Mae Howard’s work is a call against the art institution’s pigeonholing tendencies into discrete formal languages and media of expression. It should not be forgotten that those tendencies are also channeled through modes of collecting as well as displaying art objects.