The first thing visitors hear upon entering the foyer of Fridericianum is a swelling, deeply unsettling noise. Cascade-like, akin to an air raid siren or an earthquake, Roberto Cuoghi’s LAŠ (2018) reverberates through the building. It is part of an exhibition that assembles works by the 1973-born artist. Not quite a retrospective, the show provides an abridged survey of some of Cuoghi’s obsessions.

Not included in the exhibition are activities from Cuoghi’s early practice of the 1990s, which survive only as a rumor. The artist ate and ate to increase his body mass, dressed like his father, dyed his hair gray, and lived as a middle-aged man for seven years. Paradoxically, as he strove to shed his old self, he wanted to disappear by growing. In another instance, while attending art school in Milan after he took up psychology and other sciences, he grew out his nails, making everyday life almost impossible. For one work he wore, for days at a time, glasses with prisms that flipped his vision horizontally and vertically. Cuoghi, who mostly stays away from the art world’s limelight, gained a reputation for making difficult work, and colleagues and curators were intrigued by the extremes to which he went.

The exhibition in Kassel roughly focuses on the past ten years, and it foregrounds work that has been on view at institutions mostly outside of Germany. Cuoghi has been shown at the Venice Biennale three times. In 2017 he represented his native Italy, and some say he was a close contender for the Golden Lion. Other institutions he has showed in include the MADRE in Naples, the New Museum in New York, and the Castello di Rivoli in Turin.

His Biennale pavilion is as good a starting point as any, perhaps with the added benefit that its symbolism is more readable, at least at first glance. Inside the pavilion, he created an assembly line within an inflatable transparent tent. The structure recalls the quarantine tent in the movie E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), but could also be read as a church-like setup. The show was titled “Imitatio Christi,” after the devout identification with the suffering savior. It started with body parts of Christ cast in organic, gelatinous matter sourced from algae, and from there was left to microbial intervention. Mold, bacteria, and fungi transformed the pieces into eerily lifelike morsels with their skin peeling off, recalling bog bodies or late gothic sculptures in all their morbid dedication to detail.

There is a certain studiousness to Cuoghi’s constant search for new adventures. Take the sound piece Šuillakku, originally shown in 2008, here adapted for the Fridericianum. Cuoghi studied the fall of Nineveh, which was sacked in the seventh century BCE. He recreated instruments from the period and consulted an archeologist to find out what ancient Assyrian music might have sounded like. He then learned to play the instruments and recorded them as part of a soundscape, which is played at an anxiety-inducing volume over a circular arrangement of speakers: chimes, yells, bangs, and fragments of songs create a deafening crescendo.

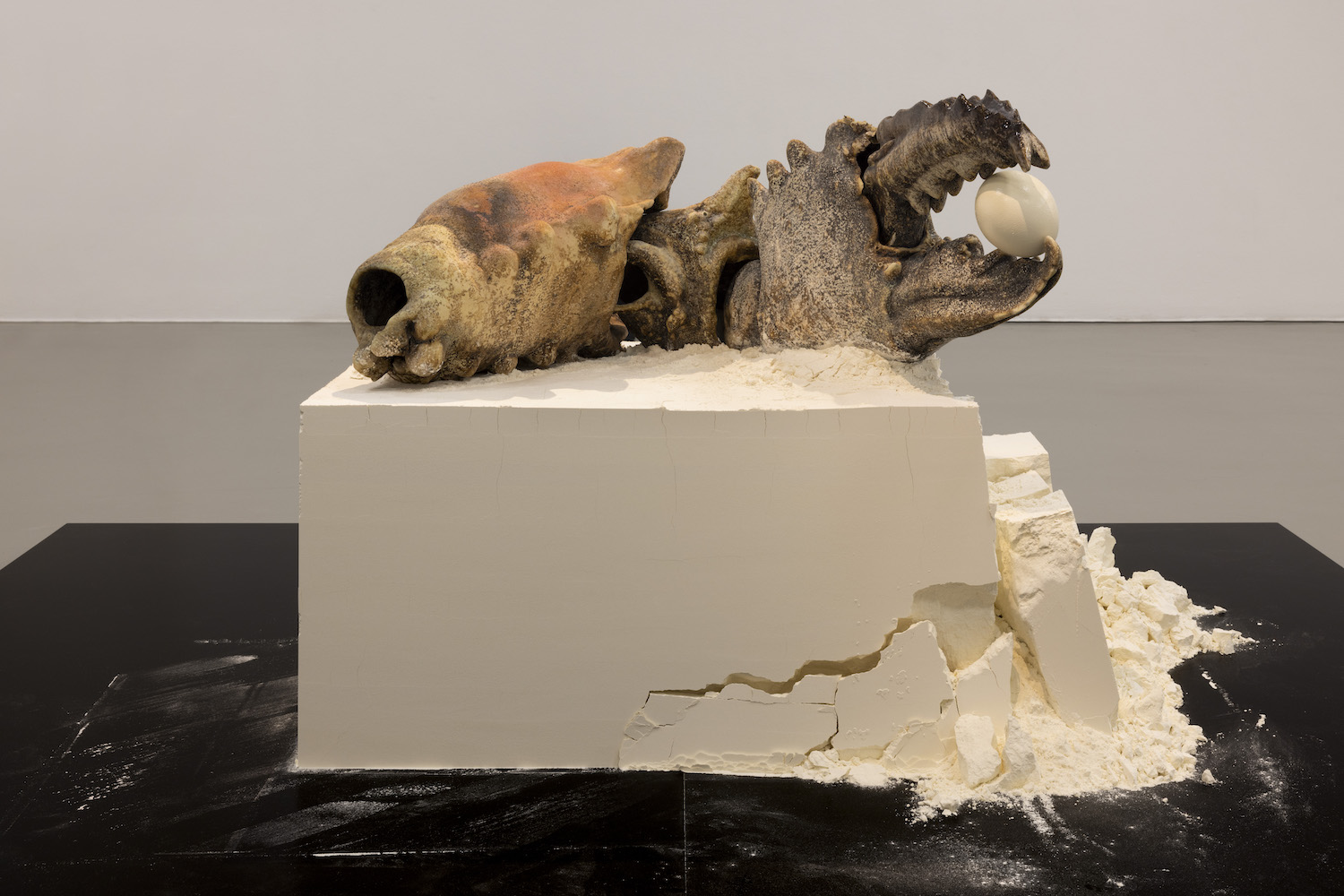

This is a close relative of LAŠ, the thundering, cathartic sound work that can be heard throughout the building. It is installed in two vast rooms on the upper floor, and the spaces mirror each other. They were created in collaboration with the French designer matali crasset, who created orange and yellow rakes, and tank-like reproductions of heavy machinery that hold pieces from “Imitatio Christi.” These two rooms also house porcelain crabs that Cuoghi made when he was invited to Hydra, where the collector Dakis Joannou has a project space. Cuoghi constructed his own kilns and made the crabs from molds. He cooled the material with an odorous, fermented brine of yeast, protein, and bird seed. The title: Putiferio (2016).

For SS(XCVP)c (2019), Cuoghi assembled a similar huge porcelain crab and a grotesquely oversized sweater, the label of which reads: mismatch / free to grow. The obsessive hermeticism of his pieces and his own personal secrecy recall the personal mythologies around outsider artists or the refusal to play by the rules of the art world that was prevalent in the ’90s. But what gets overlooked easily is Cuoghi’s sense of humor.