Robert Morris’s art is rooted in the corporeal: not only in its means of production — involving materials of heavy industry rather than fine arts — but in the way it implores the viewer to move physically when taking in sculptural volumes and optical phenomena. This approach underpins “The Perceiving Body,” an exhibition at MAMC+ (Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole) that highlights the American artist’s corpus between the early 1960s and late 1970s. Curated by Jeffrey Weiss — who worked with Morris before he died — and Alexandre Quoi, the exhibition brings together works from international collections such as the Tate Modern and the Guggenheim, but also highlights the museum’s own prescient legacy. To date, the museum holds thirteen Morris works in its permanent collection, including an untitled heavily patinated aluminum sculpture/enclosure (1968–69), presently situated in the entrance hall. It also, surprisingly, presented a Robert Morris solo exhibition in 1974, with works lent from Galerie Sonnabend in Paris.

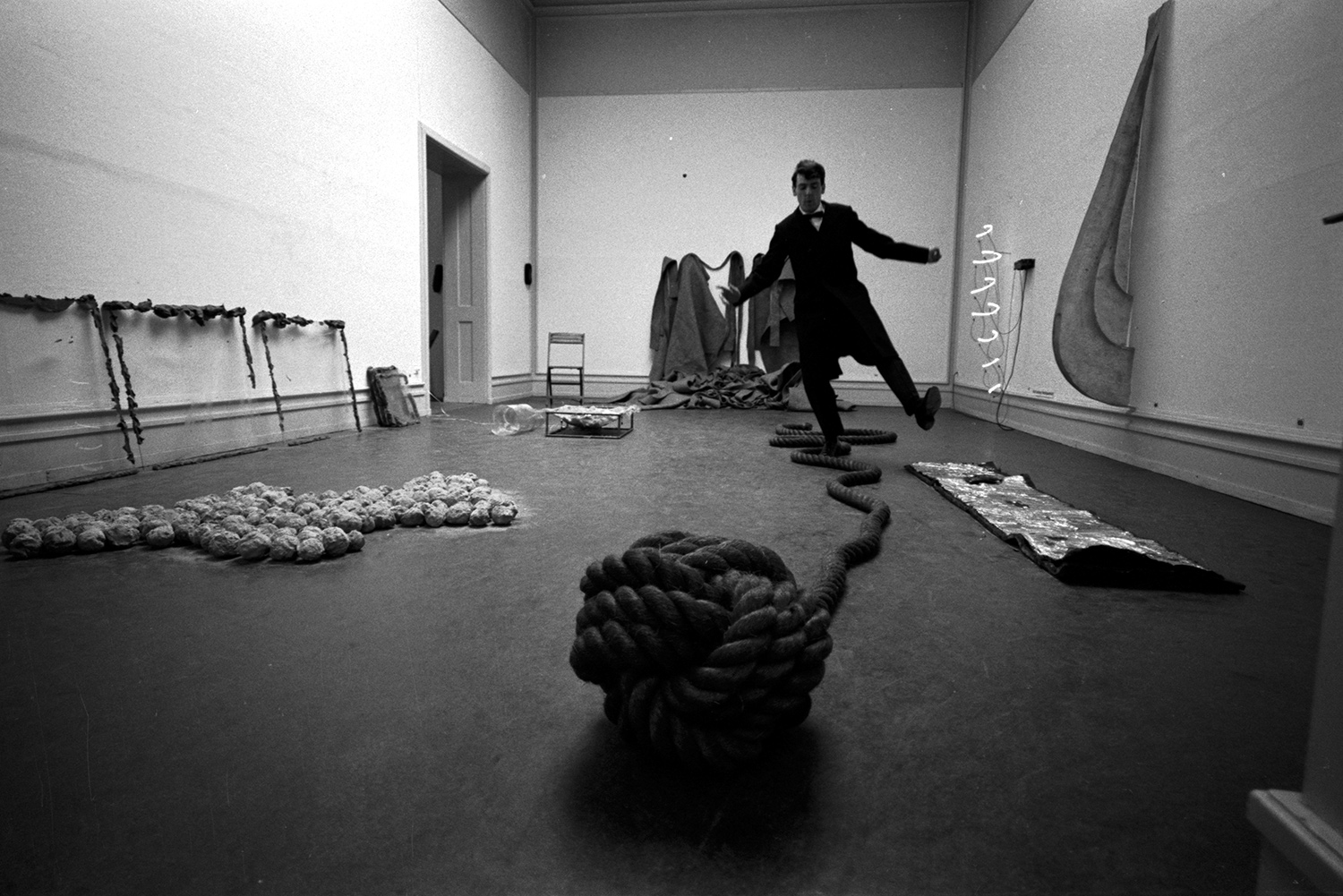

The seven rooms crosscut from Morris’s multiform output (often filed under Minimalism, although “Morris’s work always had a quality of risk that sat uneasily with the term,” as the Guardian stated in his obituary). For Morris, artistic self-expression was sublimated into orienting and disorienting the viewer’s perception. Quoi describes Morris as “imposing but not dominating”: the artist’s formal austerity belies a playfulness, something a bit sly.

Highlighting tenets of the artist’s practice — manual construction, spatial choreography, repetition, formalism, illusion — many of his pieces are refabricated without preciousness, substantiating his take on art as a process rather than a static object. The plainspoken architectural elements of three L beams in the first room, in pilgrim gray, carefully lit to emphasize their angles, seem to double down on radical simplification, but also highlight the dangers of being too trusting of any point of reference.

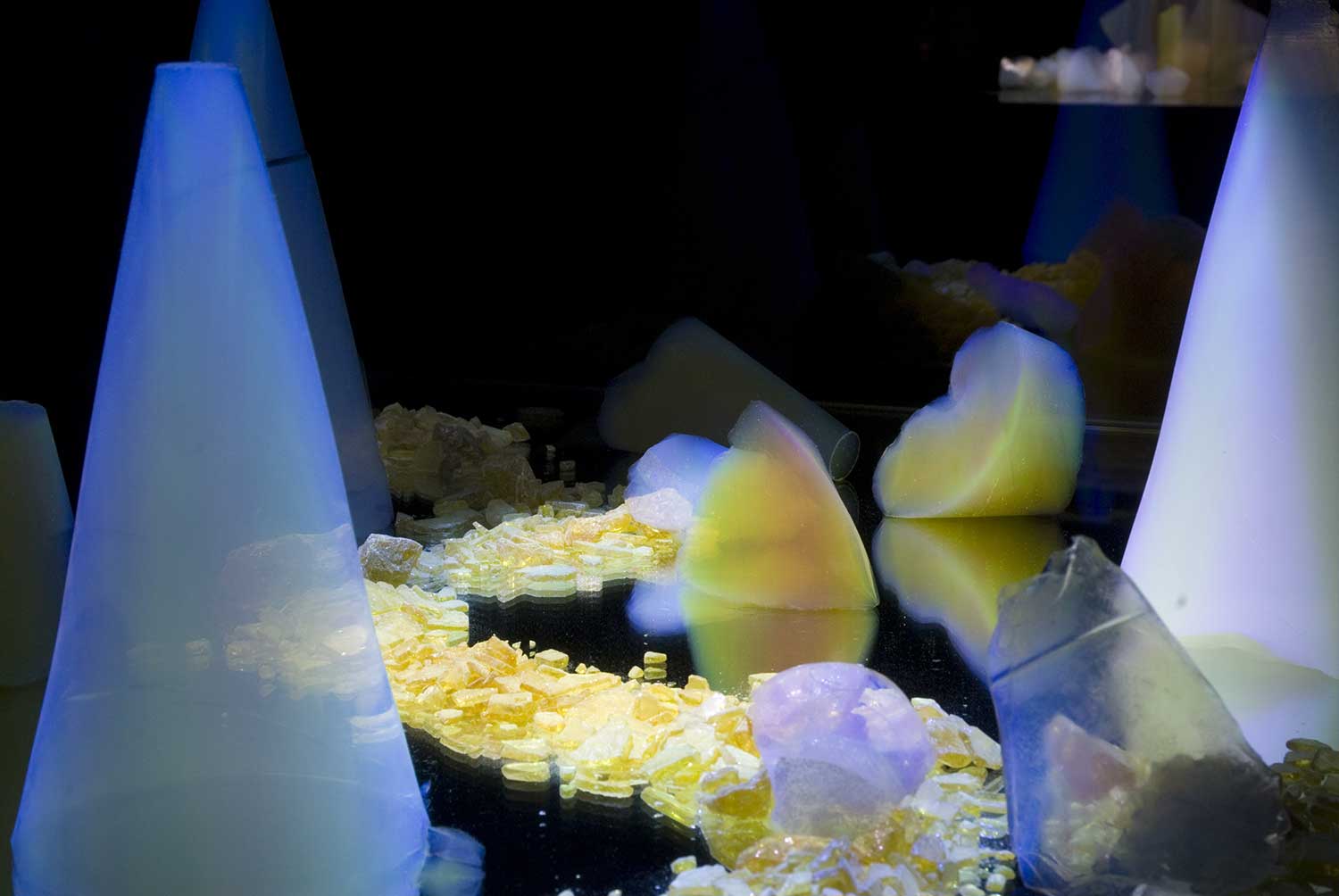

Rigid materials give way to soft ones in the next room, notably felt, which Morris hung directly on the wall and relished for its lack of fixity, cresting and pleating in cut forms reminiscent of slatted blinds and, in a more ribbony decoupage, an arachnid silhouette. Further on, the loose installation of assorted shapes and materials in Untitled (Scatter Piece) (1968–69/2009) transgressively cedes control, with Morris providing certain directives for resurrection but leaving mise-en-scène to chance and curatorial discretion. The exhibition concludes with an installation of timber and mirrors (Portland Mirrors, 1977) calculated to establish spatial parameters as unexpectedly shifty.

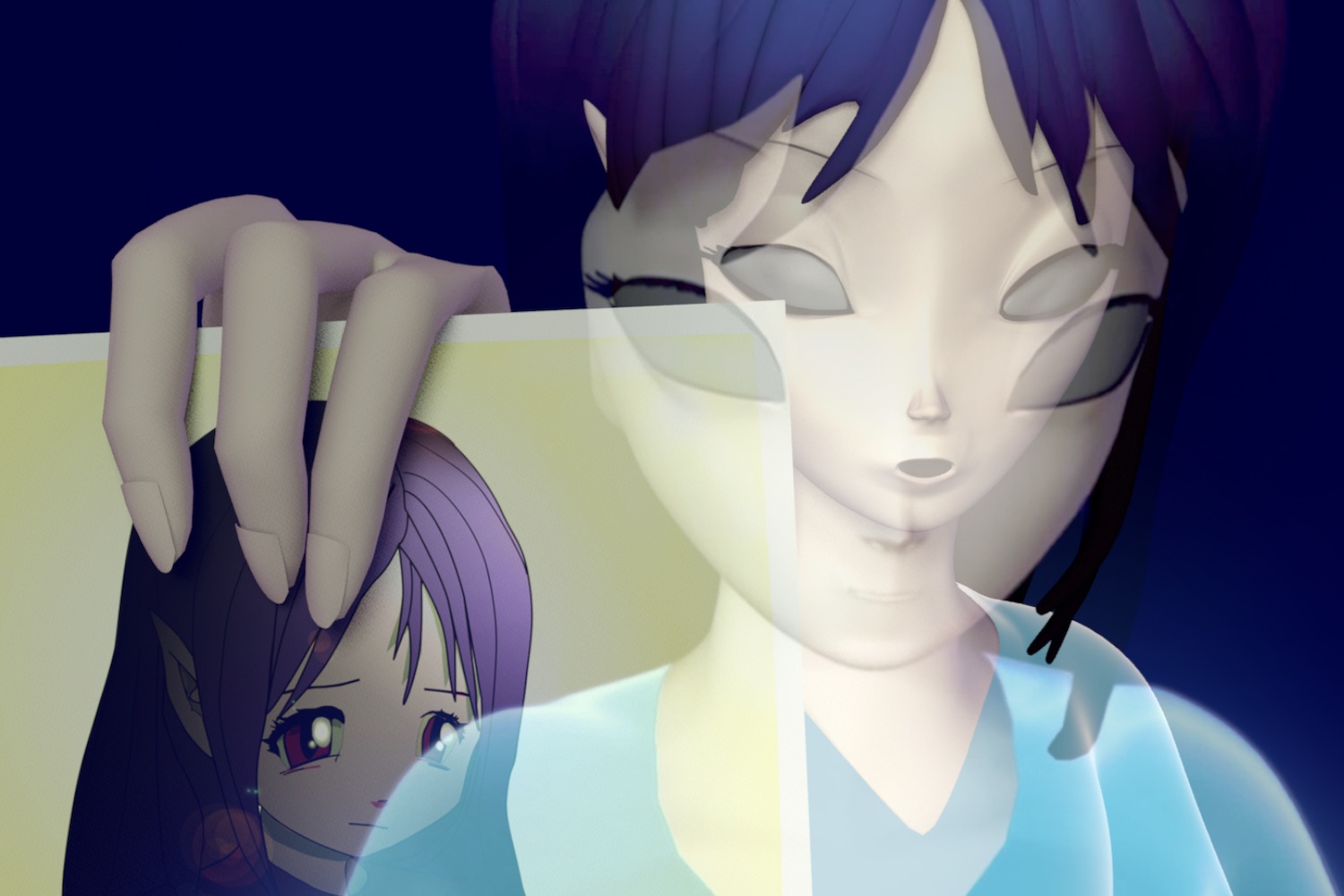

Morris’s 1969 black-and-white film Mirror, screened adjacently, further crystallizes the fickle nature of perspective. The camera captures him in a field, holding up a rectangular mirror which in turn reproduces — and unevenly frames — an outdoor panorama of snow and trees. He retreats backward, confounding the planes of vision. As he withdraws into the horizon, the mirror increasingly abstracts the world before him into something almost featureless, and little more than speculative.