Rhea Dillon is an artist whose work spans video, painting, sculpture, writing, live performance, and even olfaction. I first met her at the “War Inna Babylon” exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in Summer 2021. As fate would have it, Rhea and I ran into each other a year later in Jamaica and spent meaningful time together in Trelawny. We sat down for a third time in July 2023 to talk about her artistic practice and first institutional solo exhibition, “Rhea Dillon: An Alterable Terrain” at Tate Britain. For me, Dillon’s artwork attains beautiful aesthetic resonance as well as thoughtful reflection on deep and sometimes painful topics that are rarely explored in British and European visual art. There are sets of words that come to the front of my mind when I encounter her work:

Glass/Fragility

Each of the artworks in “An Alterable Terrain” reference one of six Black women’s body parts — mouth, feet, hands, the reproductive system, lungs, and soul. The anchor of the exhibition is a clear acrylic glass cube titled Placing Her Within An Alterable Terrain (2023). I am immediately intrigued by the work and ask Dillon which body part it gives life to. She explains that it is deliberately 160 centimeters tall, the average height of women worldwide, and is about the lungs. Here Dillon honors Ella AdooKissi-Debrah, presenting a visual consideration on the effects of air, especially in city spaces. Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah died in 2013, aged nine, from an acute asthma attack due to high levels of air pollution from the major roadway nearby her family home. “For Ella to be the first person in the UK to have air pollution o”cially listed as their cause of death, for it to be a young Black girl and for it to be in my own city, I was greatly affected.” I view Placing Her Within An Alterable Terrain as being in conversation with my own writings on Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah. My short story “The Old Heads of Elder Grove Learn About Air Pollution” was published in 2019; it draws attention to the same notion that Dillon highlights in her artwork — the fragility of Black life in the built environment and what she refers to as “a visible invisibility.” “I was thinking about what a controlled hold of air would look like,” says Dillon. Placing Her Within An Alterable Terrain gives site (and sight) to how we emotionally and artistically process and talk about environmental injustice and ecological crisis.

Head/Body

Scent is another invisible presence that Dillon gives body to. Her scent, NEGR-OID (2022), debuted in “The Sombre Majesty (or, on being the pronounced dead)” at Soft Opening in London (2022). NEGR-OID was a response to E! News “Fashion Police” pundit Giuliana Rancic’s comment that actress Zendaya “looked like she smelled of patchouli oil and weed” at the 87th Academy Awards because of her hairstyle: faux dreadlocks. I note that though Rancic made these comments in 2015 it is a pop culture moment etched in both of our memories. I ask what NEGR-OID smells like, Dillon laughs, replying, “Well, what do Black women smell like?” She pauses and answers, “It doesn’t smell like any one thing in particular because Black women don’t universally smell like one thing.” I haven’t experienced NEGR-OID but therein lies the point. Dillon and Zendaya are the same age, and both operate in entertainment and art spaces that are traditionally white, wealthy, and male. Dreadlocks is a hairstyle that millions of Black women across the world wear, including myself. Dillon’s foray into olfaction here unsettles me by pointing out that we live in a world where even something as intimate as the smell emanating from our bodies is fair game for mass consumption and discussion.

Oracle/Orator

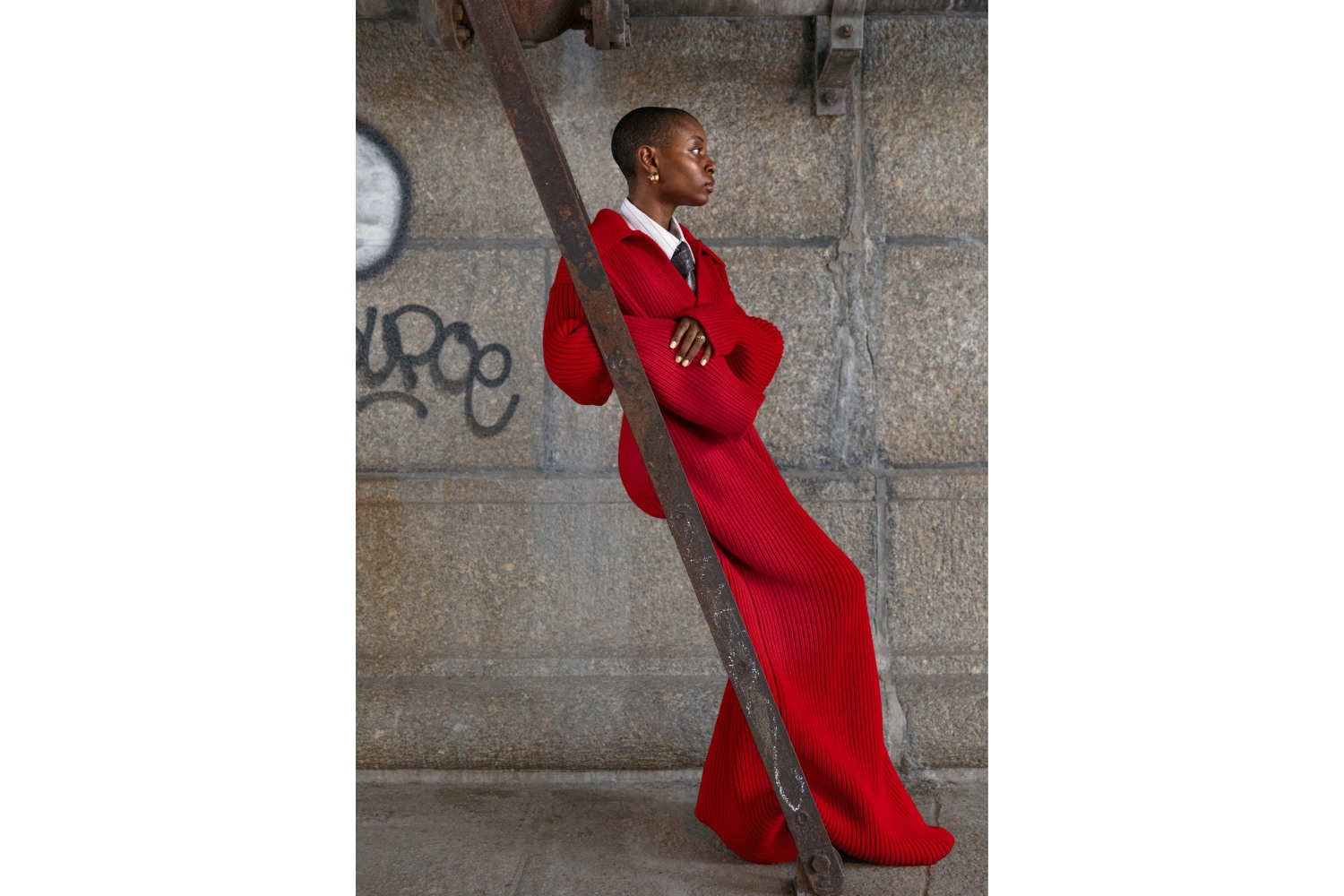

“So much of my practice is about listening to what arrives around me and through me.” This is how Dillon describes her residency at the Black Cultural Archives in London in 2020 that allowed her to take a deep dive into the collections of composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Dillon continued researching Black classical music and “Black operatics.” This work led to Catgut – The Opera, a live performance for Serpentine Gallery’s Park Nights series in the Counterspace Pavilion in 2021. Catgut – The Opera pays homage to the character of the orator, like those Dillon often sees protesting outside the House of Commons and the House of Lords on bus rides to and from her studio — the soapbox, the voice box, and the strings of our vocal cords come to mind for me here. Dillon’s costume design for Catgut – The Opera was made by Caymanian-Jamaican fashion designer Jawara Alleyne. Alleyne referenced the Black woman as oracle by citing the fantastic drapery, gowns, and headdresses of performers the I-Threes and Erykah Badu. Catgut – The Opera has been described as an “anti-performance.” “It’s about visceral and internal pulling — a ringdown,” reveals Dillon. “It’s about me dismantling the class expectations of opera and that kind of storytelling that is innate to spirituals, innate to blackness.” The libretto of the opera was published as a book of the same name in June 2023 by Worms Publishing.

Uprooting/Mahogany

Our conversation turns to Dillon’s use of sapele mahogany for several artworks in her practice. Like Dillon, I have drawn mahogany into my work to tell the story of colonialism and environmental extraction, such as in “An Elegy for Lignum Vitae” published in The Wild Isles: An Anthology of the Best of British and Irish Nature Writing (Head of Zeus) in 2021. Dillon’s Incomprehensible Sex Coming To Its Dreaded Fruition; nothing remains but Pecola & the Unyielding Earth (2023) is a small co”n-like box, made of sapele mahogany, opened to show marigold seeds. It is in reference to Toni Morrison’s 1970 debut novel The Bluest Eye, which Dillon focused on for her solo exhibition “We looked for eyes creased with concern, but saw only veils” at Sweetwater, Berlin (2023). The protagonist, Pecola, is raped by her father and becomes pregnant, the child is born prematurely and dies. The artwork is thus reminiscent of the reproductive organs of Black women and the souls of Black babies (plus those of abused mothers). Dillon mentions that her continued choice of sapele mahogany is to bring questions of indigeneity and identity into her work. Sapele originates in West Africa and is in the same family of plants as genuine mahogany. In the late nineteenth century, sapele mahogany came to replace genuine mahogany in commercial use after the latter was greatly deforested in the Americas (its natural habitat) to feed European and North American timber markets. In Dillon’s artwork, mahogany’s use in slave ships further signals the upheaval of Europe’s slave trade of both people and nature. “The wood was brought to the Caribbean. Bodies were brought to the Caribbean, and the mahogany carried them here on ships. Everyone and everything was uprooted and affected.

Time/Offering

I am drawn to another artwork in her Tate exhibition, As Wata to Wine, Wine to Blood, Blood to Dirt, Dirt to Sand, Sand to Water; Wata (Bit) (2023), a sculpture made from iron, plastic, and sand. “Sand is imbued with so much because it’s formed over deep time,” explains Dillon. “It makes me think of who stood here before, and what happened before that remains in the sand.” We are again in agreement in our artistic conception of ground and its relationship to time. Like sand, my pamphlet, Testimonies on the History of Jamaica Volume 1 (Rough Trade Books), shows deep time compressed into a single point to call forward various Jamaican voices across four centuries of our past. As Wata to Wine, Wine to Blood, Blood to Dirt, Dirt to Sand, Sand to Water; Wata (Bit) presents a world in chaos; I think of it as the state of flux that caused the council to be convened for testimonies at the beginning of my story. The mouths of the two water bottles in As Wata to Wine, Wine to Blood, Blood to Dirt, Dirt to Sand, Sand to Water; Wata (Bit) are held together by an iron rod, evocative of an iron bit used to gag enslaved people. When Dillon visited Elmina and Cape Coast Castle in Ghana in 2021, she was struck by the number of water bottles left as offerings to the spirits of the captives brought to the coast to be shoved onto slave ships. But, “What is a drink of water to the dry mouth of the dead?” she thought. There is, however, another location and layer of meaning to this artwork. I am surprised to hear that this piece was further conceptualized from our chance meeting at a resort in Jamaica in 2022. It hadn’t occurred to me until I arrived there, but the site we were on was of the infamous “stolen beach” saga where approximately five hundred truckloads of sand were removed from a stretch of beach in Coral Springs, Trelawny, in the summer of 2008. The sand has never been found and no one has ever been held accountable. The sand in Dillon’s artwork was collected in 2022 during our stay. She collected it in the plastic “Wata” bottles, now part of the final work, as she proceeded to learn more about the incident. This work, responding to unmentionable corruption in one place and voicelessness and the lack of breath in another, serves as an inquiry into the notion of caging the tongue and being unable to speak.

* * *

With her first institutional solo exhibition in Tate Britain’s “Art Now” series on view until January 1, 2024, and an upcoming catalogue to accompany the display (edited by herself and featuring an introduction by geography professor Pat Noxolo), Dillon presents a captivating body of work commenting on Black women, the human body, psychoanalysis, the environment, the Caribbean, and colonial history.